The Importance of Diagnosis in Centric Relation in Orthodontics

Machine translation

Original article is written in ES language (link to read it) .

Summary

The correct function of the stomatognathic system, its basic functions such as phonation, swallowing, and chewing, is an area of interest for all dental specialties. Currently, there is still debate, as there is no consensus within the dental community on rehabilitating our patients in centric relation (CR); in orthodontics, there are very strong currents or philosophies that establish orthodontic rehabilitation in centric relation. The direct approach is on dynamic diagnosis and cephalometry, as this is taken at maximum intercuspation (MI), and this is where errors can occur if manual induction to centric relation is not considered. At the same time, the use of semi or fully adjustable articulators that have an attachment indicating in mm the position of the condyle in the glenoid cavity and transferring this discrepancy to our initial cephalogram and performing the cephalometric conversion to obtain a second cephalogram from which the cephalometry for the correct diagnosis of the malocclusion in question will be carried out. Many clinicians find it difficult to manage an articulator; the cause may be inadequate training in undergraduate studies. I believe that in a postgraduate program in orthodontics, the methodical use of an articulator should be an essential subject in the diagnosis of all or at least applied to patients with TMJ dysfunctions, clinical discrepancy of maximum intercuspation or habitual occlusion, and centric relation.

Introduction

The basic functions of the stomatognathic system, such as chewing, swallowing, and phonation, depend not only on the position of the teeth in their bony bases but also on the three-dimensional relationship of the teeth with their antagonists when they occlude.

The mandibular closure reinforces a pattern of occlusal contact and maintains the dental position; if this is lost or a part of the occlusal surface of a tooth is altered, the dynamics of the periodontal support structure will allow for the displacement of the tooth. Similarly, the loss of one or more teeth results in the instability of the maxillae.

Aligning the teeth alone or according to cephalometric norms does not achieve a correct function of the stomatognathic complex; it is necessary to incorporate and apply gnathological concepts to the diagnosis, treatment planning, and achievement of orthodontic objectives.

The diagnosis of malocclusion must consider the position of its bony bases in correct centric relation, taking into account the influence of the neuromuscular system. The physiologically defined centric relation allows for normal neuromuscular function without effort, it is a stable and repeatable position, and when factors that deviate it from that position are not present or are eliminated, the best physiological health conditions of the system are obtained.

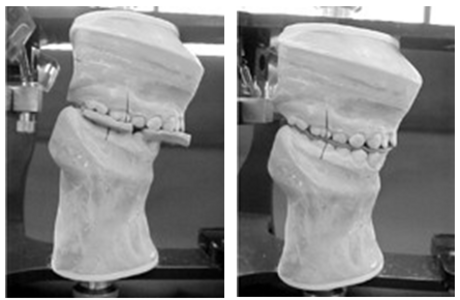

The clinical orthodontist must know and assess the health status of the TMJs, and should also induce centric relation, or use neuromuscular deprogramming plates when necessary to avoid errors in obtaining the correct mandibular position. The seating of the condyle in the glenoid cavity in the Rc position often creates a molar fulcrum where the mandible rotates to reach the Mi, when there is a discrepancy between Rc and Mi, the first point of contact that occurs during mandibular closure is generally in the posterior teeth creating a distraction of the condyle and the mandible. Clinicians must also understand the essential use of an articulator with a condylar position indicator, familiarize themselves with this instrumentation technique to assess its effectiveness and to avoid errors in orthodontic diagnosis.

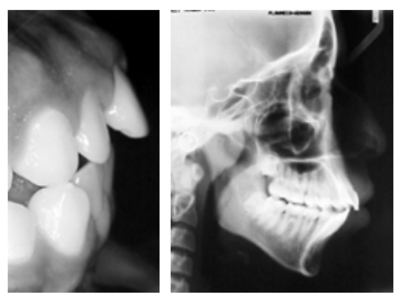

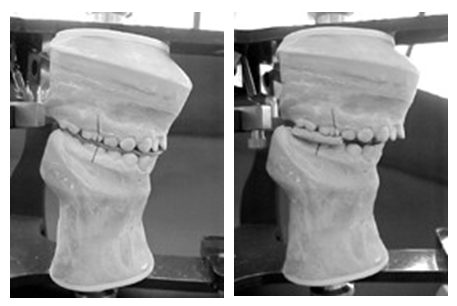

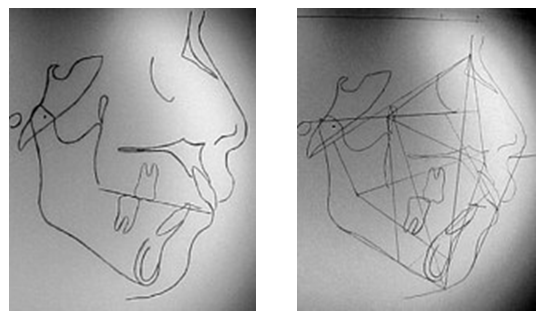

This last procedure will provide us with quantitative data in mm of the discrepancy between centric occlusion (habitual) and centric relation, which will be transferred to the cephalogram that was also obtained in habitual occlusion, and those discrepancies greater than 2.5 mm in the sagittal and vertical directions will undergo a procedure called cephalometric conversion, obtaining a second cephalogram in centric relation from which we will perform our cephalometry and obtain correct values for an accurate diagnosis.

The cephalograms obtained with the patient in maximum intercuspation or habitual occlusion, from which the cephalometry is developed, are performed with the condyles in a position that depends on that occlusion, and the diagnosis currently made by many clinicians in this habitual occlusion leads us to errors. An example of the above is the following clinical case:

Case Description

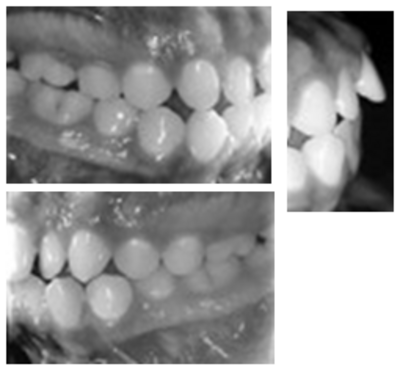

14-year-old female patient, her diagnostic summary is: Class I molar malocclusion, Class II skeletal, bimaxillary protrusion, convexity of + 14 mm, VERT of -1 (dolichocephalic).

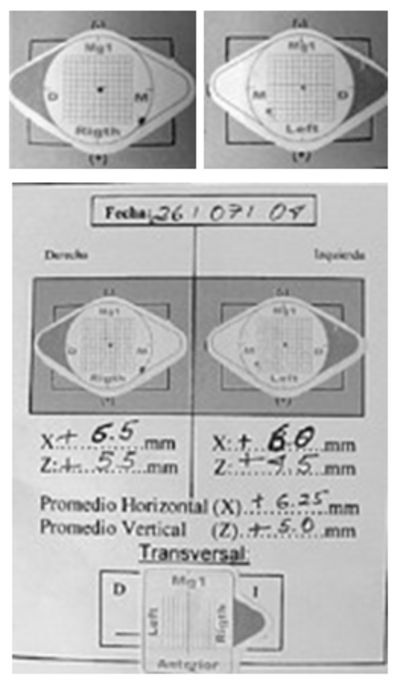

There is a significant sagittal and vertical displacement between habitual occlusion and centric relation with an average of + 6.25 mm sagittal, + 5.0 mm vertical, and 0.5 mm transverse, magnifying the Class II anomaly in centric relation and whose diagnosis could be erroneous if it were made only in static and in maximum intercuspation (Figures 1-8).

Discussion

In the 21st century, there is still debate about the diagnosis in centric relation in dentistry. We recognize that there are many limitations, the first being economic and the second being a superficial and simple diagnosis without delving into the causal origin of malocclusion. I believe we must make the change to achieve a correct diagnosis in centric relation in dentistry, and even more so in orthodontics, needing to familiarize ourselves with instrumental diagnosis as Cordray FE mentions.

It is common to find that premature high points in our patients condition a distraction of the condyle and mandible, creating double bites or significant sagittal, vertical, or transverse discrepancies that alter the diagnosis in orthodontics, widely described by many authors.

In orthodontic diagnosis, it is necessary to consider the mandibular position in Rc and determine the existing variation up to the Mi or habitual occlusion, avoiding diagnostic errors when quantifying this displacement before, during, and after orthodontic treatment, being of vital importance, as well as reducing it or having Rc coincide with Mi to ensure a physiologically healthy occlusal and joint stability.

References:

- Axel B, Ulrich L. Atlas of functional diagnosis and therapeutic principles in Dentistry. Barcelona, Spain: Ed. Masson; 2000.

- Jorge G. Orthodontics and orthognathic surgery diagnosis and planning. Barcelona, Spain: Ed. Expaxs; 1998.

- Alonso-Albertini-Beckelli. Occlusion and diagnosis in oral rehabilitation. Argentina: Ed. Panamericana; 2000.

- Escobar PH. The cephalometric conversion and overlapping areas. Rev Gnathos 2003; I: 22-9.

- Roth RH. The maintenance system and occlusal dynamics. Den Glin North Am 1976; 20: 761-88.

- Slavicek R. Clinical and instrumental functional analysis for diagnosis and treatment planning. Part IV: instrumental analysis of mandibular casts using the mandibular position indicator. J Glin Orthod 1998; 22: 566-75.

- Meyer W, Hondrum, Thomas WU. Condylar position changes with MPI. Am J Orthod Dentof Orthop 1995: 107: 298-308.

- Keshvad A, Winstanley RB. An appraisal of the literature on centric relation. Part III. J Oral Rehabilitation 2001; 28(1): 55-63.

- Wood DP, Elliot RW. Reproducibility of the centric relation bite registration technique. Angle Orthod 1994; 64(3): 211-21.

- Cordray FE. Centric relation treatment and articulator mountings in orthodontics. Angle Orthod 1996; 2: 153-8.

- Calderón JG. Roth-Williams objective orthodontics. Rev Odontología Actual 2003; 1(3): 40-3.

- Espinosa SR. History of gnathology. Rev Odontología Actual 2003; 1(4): 7-12.

- Calderón JG. Roth-Williams. Rev Odontología Actual 2003; 1(4): 38-51.

- Steven RA, Robert NM, Linda MD. Mandibular condyle position: comparison of articulator mountings and magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Orthod Dentof Orthop 1993: 104: 230-9.

- Hatice G, Harcan T. Changes in position of the temporomandibular joint disc and condyle after disc repositioning appliance therapy: a functional examination and magnetic resonance imaging study. Angle Orthod 2000; 70: 400-8.