Comparative accuracy of the Clearing Technique, CBCT and Micro-CT methods in studying the mesial root canal configuration of mandibular first molars

Abstract

Aims: To compare the accuracy of the clearing technique and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) in the assessment of root canal configurations using micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) imaging system as the reference standard.

Methodology: Thirty-two mesial roots of mandibular first molars, selected on the basis of micro-CT scans (voxel size: 19.6 μm) and presenting several canal configurations, were evaluated using 2 CBCT scanners (voxels sizes: 120 μm and 150 μm) followed by the clearing technique. Two examiners analysed the data from each method and classified the anatomical configuration of the mesial canal according to Vertucci’s system. Data were compared using Fisher’s exact and chi-square tests. Reliability for each assessment was verified by the kappa test, and significance level was set at 5%.

Results: Kappa value indicated a high level of agreement between the examiners. Detection of type I configurations was significantly lower in cleared teeth (P < 0.05), whilst type II root canals were detected in all specimens by both tests (P > 0.05). In mesial roots with variable anatomical configurations, CBCT and the clearing method were significantly less accurate than the reference standard (P < 0.05).

Conclusion: Within the tooth population studied, accuracy of identifying mesial root canal configuration was influenced greatly by the evaluation method and the type of anatomy. Detection of type I configurations in cleared teeth was significantly lower, whilst type II configurations were detected in all specimens by both methods. In mesial roots with variable anatomical configurations, neither CBCT nor clearing methods were accurate for detecting the actual root canal anatomy.

Introduction

The mesial root of mandibular molars has one of the most complex internal anatomies in the human dentition, due to the high prevalence of curvatures, isthmuses, fins and multiple canals that join and separate at different levels of the root (Villas-Boas et al. 2011). Because of this complex configuration, this root has been the focus of several anatomical studies using methods that include plastic resin injection, radiography, histology, scanning electron microscopy, conventional computed tomography (CT) and clearing of samples with ink injection (de Pablo et al. 2010). Undoubtedly, these methodological approaches have been successfully used over many decades providing useful information to clinicians. However, inherent limitations, repeatedly discussed in the endodontic literature, have encouraged the search for newer methodologies that could potentially surpass the anatomical challenges that the human dentition exhibit.

An ideal technique for the study of root canal anatomy would be the one that is not only accurate, simple, nondestructive, but also and most importantly, feasible and reproducible in an in vivo scenario (Neelakantan et al. 2010b, Zhang et al. 2011). Improvements in digital imaging systems have enabled in vivo evaluation of root canal anatomy using nondestructive methods, such as cone beam CT (CBCT) (Wang et al. 2010). CBCT techniques improve the detection of additional roots and canals, including the mesiopalatal canal of the mesiobuccal root of maxillary molars, when compared to two-dimensional digital radiography (Eder et al. 2006, Matherne et al. 2008, Blattner et al. 2010). On the other hand, in an ex vivo scenario, nondestructive micro-computed tomographic techniques (micro-CT) has gained popularity because they provide accuracy, high-resolution, and can be used for detailed quantitative and qualitative measurements of root canal anatomy (Peters et al. 2000, Plotino et al. 2006, Ordinola-Zapata et al. 2013, Versiani et al. 2013).

Despite the considerable number of studies published on the internal anatomy of posterior teeth, very little information exists regarding the accuracy of clearing, CBCT and micro-CT methods to identify the morphology of the root canal anatomy (Lee et al. 2014, Maret et al. 2014, Kim et al. 2015). Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the accuracy of the clearing technique and CBCT scanning in the assessment of the mesial root canal configuration of mandibular first molars, using a micro-CT imaging system as a reference standard. The null hypothesis tested was that there was no difference in the accuracy of these methods in determining root canal configuration in the mesial root of mandibular first molars.

Material and methods

Micro-CT scanning

After local Ethics Committee approval (protocol 131-2010), a total of 75 extracted human mandibular first molars were scanned in a micro-CT device (SkyScan 1174v2; Bruker-microCT, Kontich, Belgium) at 50 kV, 5300-ms exposure, rotation step of 0.8, 360o degree of rotation, and an isotropic resolution of 19.6 μm, using a 0.5-mm-thick aluminium filter. The patient gender and age were unknown, and teeth were extracted for reasons not related to this study.

Images of each specimen were reconstructed with dedicated software (NRecon v.1.6.3; Bruker-microCT) providing axial cross-sections of the internal structure of the samples. Polygonal surfaces representation of the root canals were rendered from the source images using automatic segmentation thresh-old and surface modelling with CTAn v.1.12 software (Bruker-microCT). Two experienced and previously calibrated operators classified the canal configuration of the mesial root according to Vertucci’s classification (Vertucci 2005) using Data Viewer v.1.5.1.2 (Bruker-microCT) and CTVol v.2.2.1 (Bruker-microCT) software. Based on this qualitative evaluation, thirty-two teeth with the most prevalent anatomical configurations were selected and distributed into 3 groups:

Group 1 – Type I configuration (n = 10): Presence of a single and continuous isthmus connecting the mesiobuccal and mesiolingual canals, from the coronal to the apical third, ending in one main foramen.

Group 2 – Type II configuration (n = 10): Two separate canals leaving the pulp chamber, but merging short of the apex to form a single canal (2-1 configuration).

Group 3 – Anatomical configurations that did not fit into Vertucci’s configuration system (n = 12).

CBCT scanning

After fixing the crown in a wax base, the selected molars were scanned with ProMax 3Ds (90 kVp, 12 mA, FOV size 4 9 5 cm, 0.15 mm voxel size) (Planmeca, Helsinki, Finland) and Pax-i 3D (75 kVp, 10 mA, FOV size of 5 9 5 cm, 0.12 mm voxels) (Vatech, Fort Lee, NJ, USA) CBCT devices. All images were exported to a desktop computer with a high-resolution LCD monitor (Samsung SyncMaster 2220WM 22-inch; Samsung, Seoul, South Korea), which allowed modification of the viewer presets, including angulation or contrast, according to individual preference (Fernandes et al. 2014).

Clearing method

For the clearing procedures, a modified protocol from previously published studies was used (Sert & Bayirli 2004, Lee et al. 2014). Briefly, after access cavity preparation, the specimens were demineralized in 5% nitric acid at room temperature. The acid was changed daily, and the end-point of this process was determined by taking radiographs of the teeth. After thorough washing of the demineralized teeth in running water for 2 h, the samples were dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol (60% for 8 h, 80% for 4 h, and 96% for 2 h) and the samples were rendered transparent by immersing in methyl salicylate for 2 h. To demonstrate the canal anatomy, Indian ink was injected into the pulp chamber with a 27-gauge needle on a plastic syringe and the aid of negative pressure. The cleared teeth were examined under a clinical microscope (Zeiss, Weimar, Germany) at 10 9 magnification.

The evaluation of the CBCT images and clearing teeth was performed by 2 pre-calibrated and experienced examiners following the Vertucci’s classification system (Vertucci 2005). The same examiners repeated the evaluation 2 weeks later to validate the screening process. After the analysis, the evaluators were able to see the micro-CT reconstructions using Dataviewer software (Data Viewer v.1.5.1.2; Bruker-microCT) and observing the 3D models of the evaluated teeth (CTVol v.2.2.1; Bruker-microCT). Subsequently, the results for both methods were obtained, and the evaluators defined their answers as correct or incorrect using micro-CT reconstructions as the reference standard for comparison.

Statistical analysis

Data referring to the CBCT and clearing technique methods were statistically compared with the micro-CT analysis using Fisher’s exact and chi-square tests. Intra- and interexaminer reliabilities for each assessment were verified by the kappa test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad InStat software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) with a level of significance set at 5%.

Results

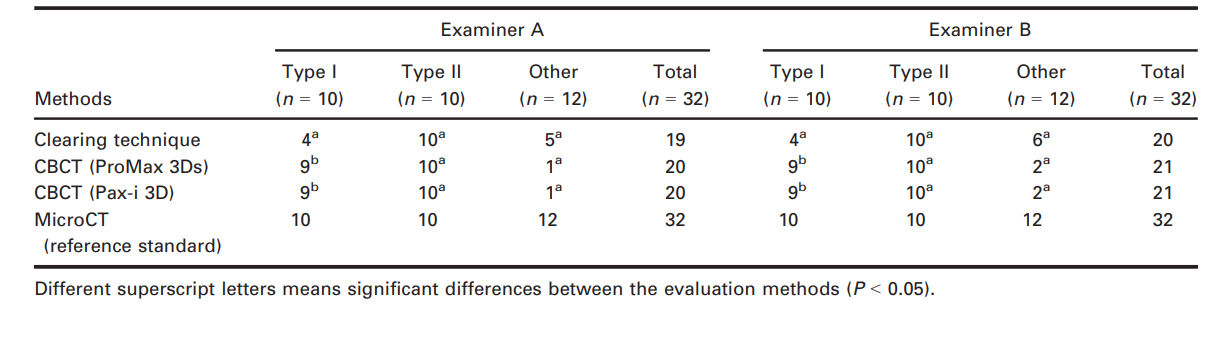

Table 1 displays the concordance results amongst the examiners related to the configuration of mesial root canal systems based on the CBCT images and clearing method in comparison with the micro-CT imaging. Identification of type I anatomical configuration (group 1) was significantly lower only in the cleared teeth (P < 0.05), whilst type II configuration (group 2) was precisely identified by both methods (P > 0.05). On the other hand, considering the anatomical configurations that did not fit into Vertucci’s classification (group 3), the chi-square test revealed a significant difference between the test methods and the micro-CT reference standard (P < 0.05). Thus, the null hypothesis tested was rejected.

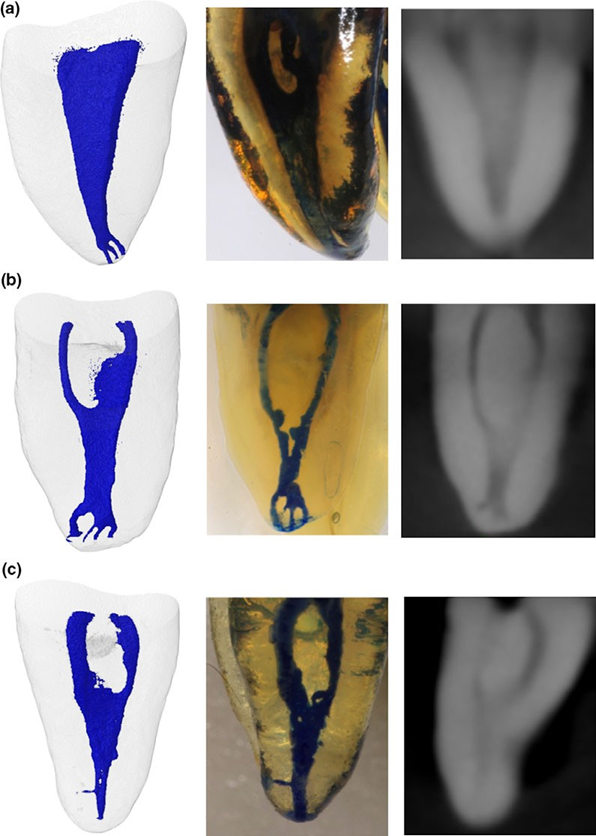

The kappa values in the evaluation of the CBCT images (0.97–1.00) and cleared teeth (0.84 and 0.88) indicated a high level of agreement between the evaluators. The intra-examiner kappa values of 0.97 and 1 for the clearing technique and between 0.94 and 0.97 for CBCT also indicated a high-level agreement for both evaluations. Representative images of the root canal anatomy acquired from a micro-CT device, the clearing technique and CBCT imaging systems are shown in Fig. 1.

Discussion

For several decades, the clearing technique was considered the best available method for the morphological study of the root canal system and its variations (Vertucci 2005, de Pablo et al. 2010). This method renders the tooth transparent through demineralization after injecting fluid materials such as molten metal, gelatine or ink (Vertucci 1984). The main limitation of this technique is that it produces irreversible changes in the tooth structure and creates artefacts, which may not accurately reflect the actual root canal morphology (Grover & Shetty 2012, Lee et al. 2014, Kim et al. 2015).

In the present study, whilst the test methods were able to identify accurately the less intricate Vertucci’s type II root canals (group 2), the clearing technique was associated with the lowest accuracy for detecting Vertucci’s type I (group 1) and more complex (group 3) anatomical configurations. Actually, in groups 1 and 3, the lack of dye diffusion distorted the internal anatomy of the specimens resulting in a different root canal configuration (Fig. 1a). This finding was also observed in two previous studies in which cleared teeth showed less fine anatomical details compared to micro-CT images (Kim et al. 2015, Lee et al. 2014), confirming that the clearing method was more technique sensitive than 3D imaging technologies. The limitations of the clearing technique might be explained by the dye solution not flowing laterally into delicate anatomical structures such as isthmuses or fins, an analogous effect that also happens to irrigation solutions even after the enlargement of the root canal system (de Gregorio et al. 2009, 2012, Susin et al. 2010).

It is important to point out that Vertucci proposed his classification system several years before the introduction of micro-CT technology in endodontic research. The advent of micro-CT imaging system overcomes several methodological limitations of the clearing technique and allows the reporting of several new anatomical variations and complexities of the root canal anatomy in the human dentition (Ordinola-Zapata et al. 2015) that were not included in previous classifications. Therefore, the introduction of these new anatomical configurations needs to be considered in a future root canal classification system.

Recently, CBCT was used in ex vivo and in vivo studies to evaluate root canal anatomy in different groups of teeth (Neelakantan et al. 2010a). However, to date only a few studies have compared the accuracy of CBCT techniques to micro-CT or histological methods in detecting different canal configurations. Michetti et al. (2010) found a high correlation between CBCT images (voxel size of 75 μm) and histological sections. However, only 9 specimens, including 3 molars, were studied. Marca et al. (2013) compared the variations of root canal cross-sectional area in three-rooted maxillary premolars using CBCT (voxel size of 200 μm) and micro-CT (voxel size of 34 μm) imaging systems, and concluded that CBCT produced the poorest images in terms of detail. Fernandes et al. (2014) reported that CBCT was able to identify multiple canals in mandibular incisors, but failed to detail their two-dimensional aspects, when compared to micro-CT assessment. On the other hand, two previous studies reported no difference between CBCT and micro-CT in detecting the mesiopalatal canal (MB2) in the mesial root of maxillary molars (Blattner et al. 2010, Domark et al. 2013). However, the simple evaluation criteria used in these studies (presence or absence of the MB2) can explain this similarity. Unfortunately, because of differences in the methodological designs and the limited published data addressing this topic, comparison of published findings to the present results is difficult.

In this study, similar laboratory conditions were used for both imaging methods (micro-CT and CBCT), including the stabilization of the specimen during the scanning procedure to avoid unwanted movement, and removal of bone, soft tissue or restorations in order to obtain the best possible image quality. The results revealed a high accuracy of both CBCT devices to identify canal configuration types I and II. However, similarly to the clearing technique, lack of identification of fine anatomical structures was also observed in the CBCT analysis when compared to the micro-CT images (Fig. 1). These limitations became more evident during the evaluation of mesial roots with anatomical configurations that did not fit into Vertucci’s configurations (group 3) and explain why nonclassified anatomies are rarely reported in clearing or CBCT studies on root canal anatomy (Sert & Bayirli 2004, Peiris et al. 2008, Wang et al. 2010, Kim et al. 2013). In these studies, only 0 to 3% of mesial and distal root canals of mandibular molars had anatomical configurations that could not be categorized using Vertucci’s parameters. In contrast, studies using micro-CT technology have shown different anatomical configuration types in 13 to 18% of the evaluated sample (Harris et al. 2013, Leoni et al. 2014, Filpo Perez et al. 2015).

Several resources available in the imaging systems used herein may also explain the difference in the results amongst the methodologies tested. For instance, nondestructive CBTC and micro-CT methods allow for the cross-sectional analysis of the specimens, which is not feasible with the clearing technique. On the other hand, micro-CT provides a better assessment of fine anatomical structures because of the possibility of using a higher exposure time (~40 min) and lower voxel size (19.6 μm) than CBCT (exposure time: 20 sec; voxel size: 120– 150 μm) during the scanning procedure. Additionally, the possibility of micro-CT devices to acquire imaging projections using a higher degree rotation of the specimen (360°) in comparison with Planmeca CBCT unit (200°) allowed the development of a more accurate and detailed 3D models of the root canal space.

Even though the CBCT system used in the present study could be hampered by insufficient spatial resolution and slice thickness, this limitation was restricted only to more complex anatomical configurations in which fine ramifications were present, but not in Vertucci’s types I and II root canal configurations. However, further studies are necessary to evaluate the ability of new CBCT scanners with voxel sizes lower than 80 μm for detecting minimal anatomical structures of the root canal system. Furthermore, other variables such as bone, soft tissues and slight movements of the specimen, which are present during CBCT acquisition in a clinical set-up, must be included in future experiments (Hassan et al. 2012).

It is important to point out that the clearing technique, micro-CT and CBCT imaging systems have different scopes; whereas the two former methodologies are used only in laboratory studies, the CBCT technique is commonly used as a diagnostic aid in clinical endodontics. Thus, in a clinical setting, when abnormal findings are evident on periapical digital films or variations are detected with magnification, it may be impossible to evaluate the root canal system effectively. In these situations, it is sensible to use CBCT for further diagnosis. Thus, CBCT techniques can still provide helpful clinical information. On the other hand, notwithstanding the limited clinical applicability of micro-CT technology, this method has been proven to be the current reference method for the ex vivo study of root canal anatomy and allows for future comparison and continuous improvements of the CBCT scanners.

Conclusions

Accuracy in the identification of the canal configuration in the mesial root of mandibular first molars was highly influenced by the evaluation method and the type of anatomy. Detection of Vertucci’s type I configuration in cleared teeth was significantly low, whilst type II configuration could be detected by both methods. In mesial roots showing variable anatomical configurations, neither CBCT nor clearing methods were accurate for detecting the correct canal anatomy.

Authors: R. Ordinola-Zapata, C. M. Bramante, M. A. Versiani, B. I. Moldauer, G. Topham, J. L. Gutmann, A. Nuñez, M. A. Hungaro Duarte, F. Abella

References:

- Blattner TC, George N, Lee CC, Kumar V, Yelton CD (2010) Efficacy of cone-beam computed tomography as a modality to accurately identify the presence of second mesiobuccal canals in maxillary first and second molars: a pilot study. Journal of Endodontics 36, 867–70.

- Domark JD, Hatton JF, Benison RP, Hildebolt CF (2013) An ex vivo comparison of digital radiography and cone-beam and micro computed tomography in the detection of the number of canals in the mesiobuccal roots of maxillary molars. Journal of Endodontics 39, 901–5.

- Eder A, Kantor M, Nell A et al. (2006) Root canal system in the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar: an in vitro comparison study of computed tomography and histology. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiology 35, 175–7.

- Fernandes L, Dwight D, Ordinola-Zapata R et al. (2014) Root canal system in the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar: an in vitro comparison study of computed tomography and histology. Journal of Endodontics 40, 42–5.

- Filpo Perez C, Bramante CM, Villas-Boas M et al. (2015) Micro-CT analysis of the root canal morphology of the distal root of mandibular first molar. Journal of Endodontics 41, 231–6.

- de Gregorio C, Estevez R, Cisneros R, Heilborn C, Cohenca N (2009) Effect of EDTA, sonic, and ultrasonic activation on the penetration of sodium hypochlorite into simulated lateral canals: an in vitro study. Journal of Endodontics 35, 891–5.

- de Gregorio C, Paranjpe A, Garcia A et al. (2012) Efficacy of irrigation systems on penetration of sodium hypochlorite to working length and to simulated uninstrumented areas in oval shaped root canals. International Endodontic Journal 45, 475–81.

- Grover C, Shetty N (2012) Methods to study root canal morphology: a review. Endodontic Practice Today 6, 171–82.

- Harris S, Bowles W, Fok A, McClanahan S (2013) An anatomic investigation of the mandibular molar using micro-computed tomography. Journal of Endodontics 39, 1374–8.

- Hassan BA, Payam J, Juyanda B, van der Stelt P, Wesselink PR (2012) Influence of scan setting selections on root canal visibility with cone beam CT. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiology 41, 645–8.

- Kim SY, Kim BS, Woo J, Kim Y (2013) Morphology of mandibular first molars analyzed by cone-beam computed tomography in a korean population: variation in the number of roots and canals. Journal of Endodontics 39, 1516– 21.

- Kim Y, Perinpanayagam H, Lee JK et al. (2015) Comparison of mandibular first molar mesial root canal morphology using micro-computed tomography and clearing technique. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 73, 427–32.

- Lee KW, Kim Y, Perinpanayagam H et al. (2014) Comparison of alternative image reformatting techniques in micro-computed tomography and tooth clearing for detailed canal morphology. Journal of Endodontics 40, 417–22.

- Leoni GB, Versiani MA, Pécora JD, Sousa-Neto MD (2014) Micro-computed tomographic analysis of the root canal morphology of mandibular incisors. Journal of Endodontics 40, 710–6.

- Marca C, Dummer P, Bryant S et al. (2013) Three-rooted premolar analyzed by high-resolution and cone beam CT. Clinical Oral Investigations 17, 1535–40.

- Maret D, Peters OA, Galibourg A et al. (2014) Comparison of the accuracy of 3-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography and micro-computed tomography reconstructions by using different voxel sizes. Journal of Endodontics 40, 1321–6.

- Matherne RP, Angelopoulos C, Kulild JC, Tira D (2008) Use of cone-beam computed tomography to identify root canal systems in vitro. Journal of Endodontics 34, 87–9.

- Michetti J, Maret D, Mallet JP, Diemer F (2010) Validation of cone beam computed tomography as a tool to explore root canal anatomy. Journal of Endodontics 36, 1187–90.

- Neelakantan P, Subbarao C, Ahuja R, Subbarao CV, Gutmann JL (2010a) Cone-beam computed tomography study of root and canal morphology of maxillary first and second molars in an Indian population. Journal of Endodontics 36, 1622–7.

- Neelakantan P, Subbarao C, Subbarao CV (2010b) Comparative evaluation of modified canal staining and clearing technique, cone-beam computed tomography, peripheral quantitative computed tomography, spiral computed tomography, and plain and contrast medium-enhanced digital radiography in studying root canal morphology. Journal of Endodontics 36, 1547–51.

- Ordinola-Zapata R, Bramante CM, Villas-Boas MH, Cavenago BC, Duarte MH, Versiani MA (2013) Morphologic micro-computed tomography analysis of mandibular premolars with three root canals. Journal of Endodontics 39, 1130–5.

- Ordinola-Zapata R, Bramante CM, Gagliardi PM et al. (2015) Micro-CT evaluation of C-shaped mandibular first premolars in a Brazilian subpopulation. International Endodontic Journal 48, 807–13.

- de Pablo OV, Estevez R, Peix Sanchez M, Heilborn C, Cohenca N (2010) Root anatomy and canal configuration of the permanent mandibular first molar: a systematic review. Journal of Endodontics 36, 1919–31.

- Peiris H, Pitakotuwage T, Takahashi M, Sasaki K, Kanazawa E (2008) Root canal morphology of mandibular permanent molars at different ages. International Endodontic Journal 41, 828–35.

- Peters OA, Laib A, Ruegsegger P, Barbakow F (2000) Three-dimensional analysis of root canal geometry by high-resolution computed tomography. Journal of Dental Research 79, 1405–9.

- Plotino G, Grande NM, Pecci R, Bedini R, Pameijer CH, Somma F (2006) Three-dimensional imaging using microcomputed tomography for studying tooth macromorphology. Journal of the American Dental Association 137, 1555–61.

- Sert S, Bayirli GS (2004) Evaluation of the root canal configurations of the mandibular and maxillary permanent teeth by gender in the Turkish population. Journal of Endodontics 30, 391–8.

- Susin L, Liu Y, Yoon JC et al. (2010) Canal and isthmus debridement efficacies of two irrigant agitation techniques in a closed system. International Endodontic Journal 43, 1077–90.

- Versiani MA, Pecora JD, Sousa-Neto MD (2013) Microcomputed tomography analysis of the root canal morphology of single-rooted mandibular canines. International Endodontic Journal 46, 800–7.

- Vertucci FJ (1984) Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology 58, 589–99.

- Vertucci F (2005) Root canal morphology and its relationship to endodontic procedures. Endodontic Topics 10, 3–29.

- Villas-Boas MH, Bernardineli N, Cavenago BC et al. (2011) Micro-computed tomography study of the internal anatomy of mesial root canals of mandibular molars. Journal of Endodontics 37, 1682–6.

- Wang Y, Zheng QH, Zhou XD et al. (2010) Evaluation of the root and canal morphology of mandibular first permanent molars in a western Chinese population by cone-beam computed tomography. Journal of Endodontics 36, 1786–9.

- Zhang R, Wang H, Tian YY, Yu X, Hu T, Dummer PM (2011) Use of cone-beam computed tomography to evaluate root and canal morphology of mandibular molars in Chinese individuals. International Endodontic Journal 44, 990–9

/public-service/media/default/147/bjsSM_65311952dfadf.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/158/GMj69_65311b2333f75.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/148/ix2WY_6531196adc6ec.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/460/aU9ju_671a20a2e53f3.png)