A comparison of two techniques for the removal of calcium hydroxide from root canals

Abstract

Aim: To compare the ability of two irrigant regimens to remove calcium hydroxide (CH) mixed with different vehicles from root canal walls.

Methodology: The root canals of 92 freshly extracted bovine incisor teeth were prepared with a step-back technique and randomly assigned into two experimental groups (n = 40), whilst the remaining teeth (n = 12) served as positive and negative controls. In each experimental group, ten teeth were assigned to each CH preparation: G1 – CH powder; G2 – CH + saline solution; G3 – CH + polyethylene glycol (PEG); G4 – CH + PEG + camphorated paramonochlorophenol (CPMC). The negative control did not receive CH placement, and the positive control received the intra-canal dressing, but no subsequent removal. After 7 days, the CH was retrieved using manual or passive ultrasonic irrigation (PUI). The roots were grooved longitudinally and split into halves. Images of each half of the canal were acquired by a digital camera, and the percentage of CH coated surface area in relation to the surface area of each third of the canal was calculated. The results were statistically analysed with anova with post hoc Tukey test with the null hypothesis set as 5%.

Results: Remnants of medicament were found in all experimental groups. The positive control group had complete coverage of the canal walls with CH in contrast to the negative control (P < 0.001). Considering the cervical and middle thirds, the percentage of CH retention in G1 was significantly lower using PUI (26.6% and 32.2%, respectively) than the manual (38.7% and 46.1%, respectively) technique (P < 0.05). No significant differences were observed between G2, G3 and G4 in all thirds and the experimental groups at the apical third (P > 0.05).

Conclusions: Neither syringe injection nor PUI methods were efficient in removing the inter-appointment root canal medicaments. Remnants of medicament were found in all experimental groups regardless of the vehicle used.

Introduction

The reduction or elimination of bacteria and their by-products from the root canal system is one of the goals of root canal treatment (Byström & Sundqvist 1981). Although instrumentation procedures have improved considerably over the years, none of the existing techniques can completely clean the root canal system (Hülsmann et al. 2005). Therefore, an intracanal medicament with profound antibacterial activity against most of the bacterial strains identified in root canal infections is required (Siqueira & Lopes 1999, Lee et al. 2009). Amongst them, calcium hydroxide (CH) mixed with an appropriate vehicle, and left in the root canal for several days or weeks, has been widely accepted in endodontic therapy (Fava & Saunders 1999, Lee et al. 2009). The vehicle is responsible for the speed of CH dissociation into hydroxyl and calcium ions that will affect the physical and chemical properties of the material (Siqueira & Lopes 1999).

It has been reported that residual CH on the root canal walls influences dentine bond strength (Windley et al. 2003, Erdemir et al. 2004) and the penetration of sealers into dentinal tubules (Çalt & Serper 1999), markedly compromising the quality of the seal provided by the root filling (Kim & Kim 2002). The remnants could also react chemically with the sealer reducing its flow and working time (Hosoya et al. 2004). Therefore, CH dressing removal prior to the root filling becomes mandatory (Nandini et al. 2006).

The removal of CH has been investigated using a range of products and techniques (Lambrianidis et al. 1999, 2006, Kenee et al. 2006, Nandini et al. 2006, Van der Sluis et al. 2007b, Salgado et al. 2009). The most frequently described method is instrumentation of the root canal using a master apical file (MAF) and copious irrigation (Lambrianidis et al. 1999, 2006). Nevertheless, canal irregularities may be inaccessible for conventional irrigation procedures, and CH may remain in these extensions (Van der Sluis et al. 2007b). Passive ultrasonic irrigation (PUI) is more effective in dentine debris removal from the root canal walls than syringe delivery of the irrigant (Lee et al. 2004, Plotino et al. 2007). Yet very few studies have been performed to assess its efficiency on the removal of CH from root canal walls (Kenee et al. 2006, Nandini et al. 2006, Naaman et al. 2007, Van der Sluis et al. 2007b). To date, no study has been conducted to analyse the removal of CH mixed with camphorated paramonochlorophenol and/or polyethylene glycol using PUI. Hence, the purpose of this ex vivo study was to compare the ability of two irrigant regimens to remove CH mixed with different vehicles from root canal walls.

Material and methods

Ninety-two freshly extracted bovine mandibular incisor teeth were used. Following extraction, the teeth were stored for 2 days in 5.25% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), at room temperature, to remove organic debris. Subsequently, they were scaled with ultrasonic instruments, washed with distilled water, and immersed in 10% formalin solution until use. To standardize the length of the specimens, each root was sectioned 18 mm from the apex, using a micro-tome with a diamond knife (Isomet 11-1180 Eow Speed Saw; Buehler, Evanston, IE, USA). The coronal portion of the canal was enlarged with Gates Glidden burs numbers four through six (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) in a low-speed contra-angle hand-piece. The pulp tissue was extirpated using a barbed broach, and the working length was established 1 mm short of the apical foramen. All canals were prepared by the same operator to a size 50 K-file at working length using a step-back technique. Irrigation was performed conventionally with 1 mL of 1% NaOCl after each file, using a 5-mL disposable plastic syringe with 27-gauge needle (Endo Eze; Ultradent Products Inc., South Jordan, UT, USA). The needle was inserted passively up to 1 mm from the working length. After root canal preparation, a size 20 K-file was passed 1 mm beyond the apex to remove any dentinal plug. A final rinse with 10 mL of normal saline solution was performed, and the root canals were dried with paper points.

Eighty specimens were randomly assigned to two experimental groups (n = 40), according to the CH removal technique: manual (group A) and PUI (group B). Then, each group was divided into four subgroups (n = 10) according to CH vehicle preparation: sub-group 1 – chemically pure CH powder (Biodinâmica, Ibiporã, PR, Brazil); subgroup 2 – CH powder mixed with saline solution (Ariston, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) at a powder to liquid ratio of 1 : 1.5; subgroup 3 – CH powder and polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG) at a powder to liquid ratio of 1 : 1.5; and subgroup 4 – CH powder, PEG and camphorated paramonochlorophenol (CPMC). In subgroup 4, the paste was prepared by initially mixing equal volumes of CPMC and PEG. Then, CH powder was mixed at a powder-to-liquid ratio of 1 : 1.5. Negative control (n = 6) did not receive CH placement, and the positive control (n = 6) received intracanal dressing, but no subsequent removal.

Pure CH powder was gradually packed with pluggers, and the insertion of CH pastes was performed using lentulo spiral carriers (size 40) in a low-speed handpiece running at a moderate speed, until the dressing protruded through the foramen. A radiograph was taken to confirm the complete filling of the canal. The access cavities were temporarily sealed with a cotton pellet and IRM (Dentsply, Petrópolis, RJ, Brazil) to a depth of 2 mm. The roots were then placed in a sponge saturated with natural water and incubated in 100% relative humidity at 37 °C for 7 days.

After this period, the temporary filling material was removed with an excavator, and two techniques were used to remove the CH. In group A (n = 40), the intracanal dressing was removed by instrumentation using the MAF in a circumferential filing action and irrigation with 15 mL saline solution. Irrigation was performed under the same conditions as in the instrumentation phase. Dressing removal in group B (n = 40) was identical to that in group A, except that, after using the MAF, a size 25 K ultrasonic file mounted on a piezoelectric handpiece (JetSonic Four; Gnatus, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil), at a power setting of three, was passively activated for 30 s at 16 mm length of the canal, plus 15 mL of saline solution irrigation. In the negative control group (n = 6), three canals were treated as in group A, and three others as in group B. Positive control group (n = 6) had no attempt to remove the intracanal dressing.

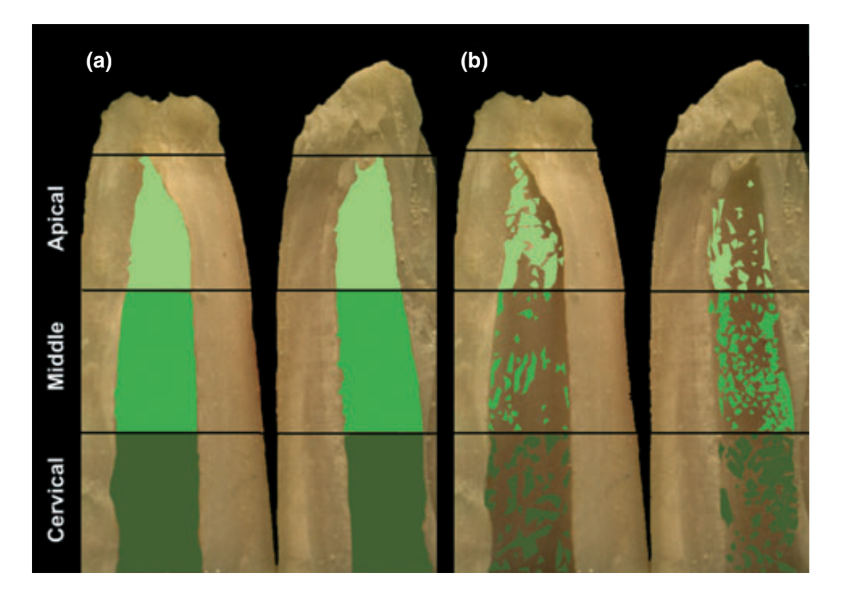

Using a cylindrical diamond bur in a high-speed handpiece, under constant water spray, all roots (n = 92) were longitudinally grooved on the buccal and lingual surfaces, preserving the inner shelf of dentine surrounding the canal, and split into halves using a hammer and chisel. Images of each half of the canal were acquired by a digital camera (Pentax Spotmatic F; Asahi Opt. Co., Tokyo, Japan) mounted on a stereoscopic microscope at x 5 magnification. Percentage of CH-coated surface area in relation to the surface area of each third of the canal was calculated using UTHSCSA Image Tool 3.0 software (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX, USA) (Fig. 1).

The results were statistically analysed with anova with post hoc Tukey test with the null hypothesis set as 5%, using spss 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

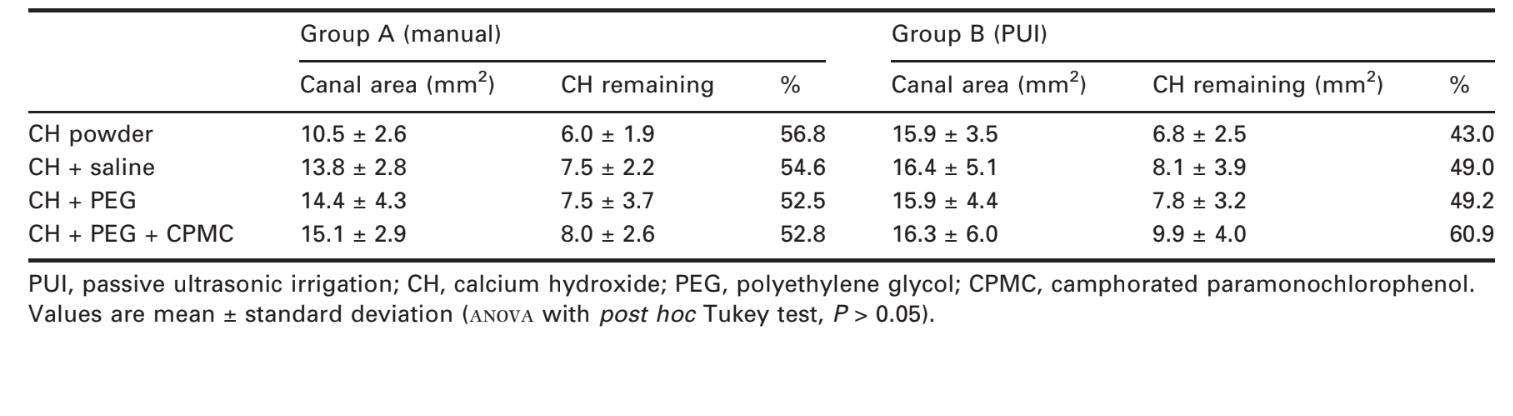

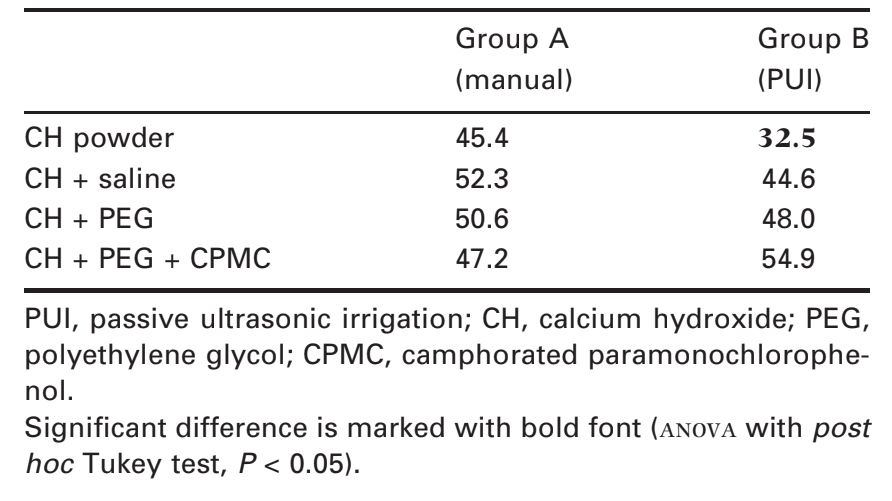

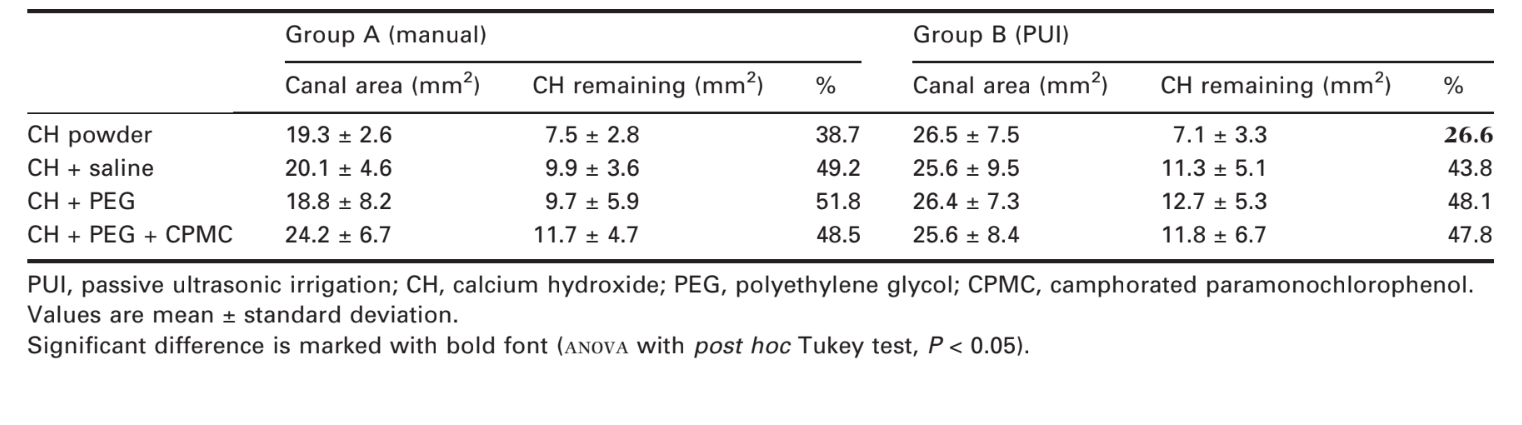

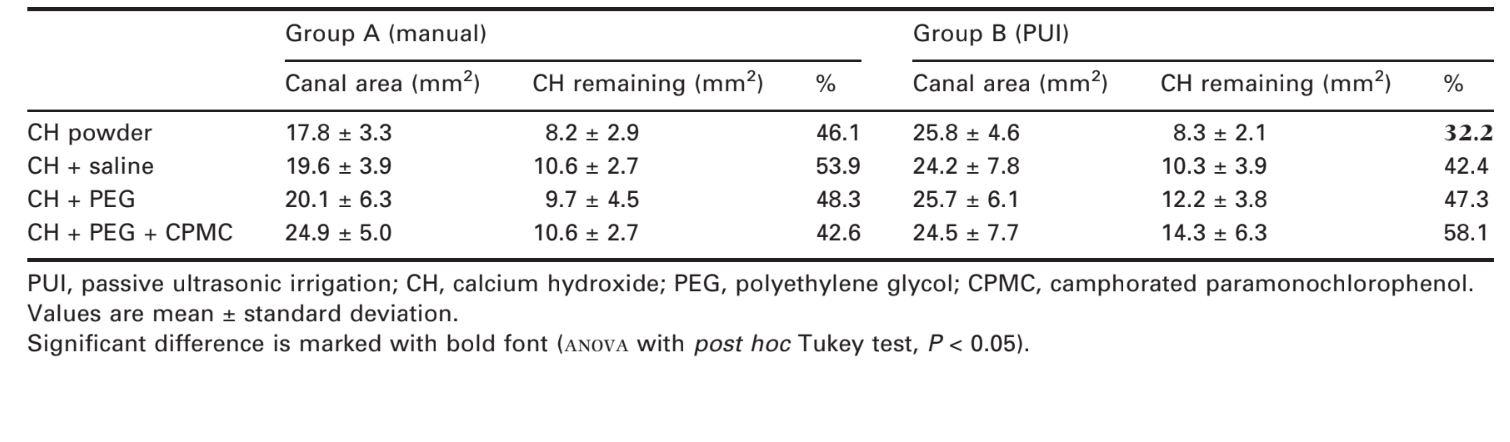

Tables 1–4 show CH retention expressed as the percentage ratio of the coated area in all canal thirds. Remnants of medicament were found in all experimental groups regardless of the removal technique or CH vehicle. The positive control group revealed complete coverage of the canal walls with CH in contrast to negative control (P < 0.001). Considering the root canal as a whole, as well as the cervical and middle thirds, the removal of chemically pure CH powder with PUI (Tables 1–3) showed significantly better results (P < 0.05) than the other experimental groups. No significant differences were observed between experimental groups for the apical third (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

Discussion

Bovine incisor teeth were used, as they have been considered a suitable substrate for screening dental materials and they are readily available and offer a distinct size advantage over human incisors, allowing strict standardization of experimental techniques (Erdemir et al. 2004). In addition, some authors have demonstrated bovine dentine to be similar to human dentine in structure, composition, and number of tubules (Ørstavik & Haapasalo 1990, Schmalz et al. 2001).

To be suitable for clinical application, an intracanal medication must be easy to introduce into the root canal, have proper contact with the tissues, and be easy to remove, to ensure effective sealing of the root filling material (Fava & Saunders 1999, Lee et al. 2009). In the present study, the percentage of CH-coated surface area in relation to the surface area of each third of the canal was calculated as reported previously (Lambrianidis et al. 1999). Concerning the control groups, six canals did not receive any CH to ensure that analysis of clean canals did not yield false positives of remaining debris; likewise, six canals received CH without subsequent removal to assure that CH was uniformly present throughout the length of the canals and that the amount initially placed was significantly different from any amounts remaining after removal attempts (Kenee et al. 2006).

The effect of ultrasonic agitation of the irrigants has been evaluated with contradictory results (Gulabivala et al. 2005, Van der Sluis et al. 2007a). Passive ultrasonic irrigation is based on the transmission of energy from an ultrasonically oscillating instrument to the irrigant inside the root canal (Van der Sluis et al. 2006, 2007a). It has been demonstrated that an irrigant solution in conjunction with ultrasonic vibration was directly associated with the removal of organic and inorganic debris from the root canal walls (Kenee et al. 2006, Van der Sluis et al. 2007b). Thus, considering that the effectiveness of irrigation could depend on both the mechanical flushing action and the chemical ability to dissolve tissue (Çalt & Serper 1999, Lee et al. 2004), in the present study an attempt was made to ensure a similar amount of the irrigant solution during manual and ultrasonic irrigation techniques (Naaman et al. 2007).

In this study, the complete removal of CH pastes from the canal walls was not obtained for the conditions tested, leaving up to 32.5% of the root canal surface covered with remnants (Table 1). This result is similar to the findings of previous studies, which showed considerable amounts of CH lingering on the canal walls, notwithstanding the removal technique used (Margelos et al. 1997, Lambrianidis et al. 1999, 2006, Hosoya et al. 2004, Kenee et al. 2006, Nandini et al. 2006, Van der Sluis et al. 2007b).

Considering the cervical and middle thirds, significantly better results were found on the removal of pure CH powder using PUI technique in comparison with the other experimental groups (Tables 2 and 3). Probably, the higher velocity and volume of irrigant flow created by PUI (Lee et al. 2004) explain its efficiency in flushing out loose CH from root canals (Van der Sluis et al. 2007b). Conversely, the flushing action from syringe irrigation is relatively weak and dependent not only on the anatomy of the root canal but also on the depth of placement and the diameter of the needle (Lee et al. 2004). Furthermore, no statistical difference was found between the experimental groups at the apical third (Table 4), probably because thorough cleaning of the most apical part of any preparation remains difficult, even with an ultrasonic device (Kenee et al. 2006, Van der Sluis et al. 2006, Naaman et al. 2007).

Despite differences in the surface tension between the CH vehicles (Özcelik et al. 2000), the results of the present study revealed that it did not influence the removal efficiency of the material from the root canal walls, suggesting that the interaction between CH and dentine is primarily mechanical. According to Pacios et al. (2003), the addition of vehicles to CH might form a protective film on hydroxyapatite crystals thus reducing the attractive action on inorganic dentine components. Conversely, these results are not in agreement with previous findings that suggested that oil-based CH pastes were more difficult to remove than CH mixed with distilled water (Lambrianidis et al. 1999, Nandini et al. 2006). The vehicles used in these studies were methyl cellulose and silicone oil. According to the authors, these vehicles, used to increase CH handling properties, resist dissolution by the aqueous irrigation solutions (Lambrianidis et al. 1999, Nandini et al. 2006). Unfortunately, there are not many studies relating to chemical interactions of CH to dentine after the application of CH pastes to the root canal.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, neither syringe injection nor PUI methods were able to remove inter-appointment root canal medicaments. Remnants of the medicament were found in all experimental groups regardless of the vehicle used.

Authors: R. P. A. Balvedi, M. A. Versiani, F. F. Manna, J. C. G. Biffi

References:

- Byström A, Sundqvist G (1981) Bacteriologic evaluation of the efficacy of mechanical root canal instrumentation in endodontic therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Dental Research 89, 321–8.

- Çalt S, Serper A (1999) Dentinal tubule penetration of root canal sealers after root canal dressing with calcium hydroxide. Journal of Endodontics 25, 431–3.

- Erdemir A, Ari H, Gungunes H, Belli S (2004) Effect of medications for root canal treatment on bonding to root canal dentin. Journal of Endodontics 30, 113–6.

- Fava LR, Saunders WP (1999) Calcium hydroxide pastes: classification and clinical indications. International Endodontic Journal 32, 257–82.

- Gulabivala K, Patel B, Evans G, Ng Y-L (2005) Effects of mechanical and chemical procedures on root canal surfaces. Endodontic Topics 10, 103–22.

- Hosoya N, Kurayama H, Iino F, Arai T (2004) Effects of calcium hydroxide on physical and sealing properties of canal sealers. International Endodontic Journal 37, 178–84.

- Hülsmann M, Peters OA, Dummer PMH (2005) Mechanical preparation of root canals: shaping goals, techniques and means. Endodontic Topics 10, 30–76.

- Kenee DM, Allemang JD, Johnson JD, Hellstein J, Nichol BK (2006) A quantitative assessment of efficacy of various calcium hydroxide removal techniques. Journal of Endodontics 32, 563–5.

- Kim SK, Kim YO (2002) Influence of calcium hydroxide intracanal medication on apical seal. International Endodontic Journal 35, 623–8.

- Lambrianidis T, Margelos J, Beltes P (1999) Removal efficiency of calcium hydroxide dressing from the root canal. Journal of Endodontics 25, 85–8.

- Lambrianidis T, Kosti E, Boutsioukis C, Mazinis M (2006) Removal efficacy of various calcium hydroxide/chlorhexidine medicaments from the root canal. International Endodontic Journal 39, 55–61.

- Lee SJ, Wu MK, Wesselink PR (2004) The effectiveness of syringe irrigation and ultrasonics to remove debris from simulated irregularities within prepared root canal walls. International Endodontic Journal 37, 672–8.

- Lee M, Winkler J, Hartwell G, Stewart J, Caine R (2009) Current trends in endodontic practice: emergency treatments and technological armamentarium. Journal of Endodontics 35, 35–9.

- Margelos J, Eliades G, Verdelis C, Palaghias G (1997) Interaction of calcium hydroxide with zinc oxide-eugenol type sealers: a potential clinical problem. Journal of Endodontics 23, 43–8.

- Naaman A, Kaloustian H, Ounsi HF, Naaman-Bou Abboud N, Ricci C, Medioni E (2007) A scanning electron microscopic evaluation of root canal wall cleanliness after calcium hydroxide removal using three irrigation regimens. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice 8, 11–8.

- Nandini S, Velmurugan N, Kandaswamy D (2006) Removal efficiency of calcium hydroxide intracanal medicament with two calcium chelators: volumetric analysis using spiral CT, an in vitro study. Journal of Endodontics 32, 1097–101.

- Ørstavik D, Haapasalo M (1990) Disinfection by endodontic irrigants and dressings of experimentally infected dentinal tubules. Endodontics and Dental Traumatology 6, 142–9.

- Özcelik B, Taşman F, Oğan C (2000) A comparison of the surface tension of calcium hydroxide mixed with different vehicles. Journal of Endodontics 26, 500–2.

- Pacios MG, De la Casa ML, De los Angeles Bulacio M, López ME (2003) Calcium hydroxide’s association with different vehicles: in vitro action on some dentinal components. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology Oral Radiology and Endodontics 96, 96–101.

- Plotino G, Pameijer CH, Grande NM, Somma F (2007) Ultrasonics in endodontics: a review of the literature. Journal of Endodontics 33, 81–95.

- Salgado RJ, Moura-Netto C, Yamazaki AK, Cardoso LN, De Moura AA, Prokopowitsch I (2009) Comparison of different irrigants on calcium hydroxide medication removal: microscopic cleanliness evaluation. Oral Surgery Oral Med- icine Oral Pathology Oral Radiology and Endodontics 107, 580–4.

- Schmalz G, Hiller KA, Nunez LJ, Stoll J, Weis K (2001) Permeability characteristics of bovine and human dentin under different pretreatment conditions. Journal of Endodontics 27, 23–30.

- Siqueira JF Jr, Lopes HP (1999) Mechanisms of antimicrobial activity of calcium hydroxide: a critical review. International Endodontic Journal 32, 361–9.

- Van der Sluis LW, Gambarini G, Wu MK, Wesselink PR (2006) The influence of volume, type of irrigant and flushing method on removing artificially placed dentine debris from the apical root canal during passive ultrasonic irrigation. International Endodontic Journal 39, 472–6.

- Van der Sluis LW, Versluis M, Wu MK, Wesselink PR (2007a) Passive ultrasonic irrigation of the root canal: a review of the literature. International Endodontic Journal 40, 415–26.

- Van der Sluis LW, Wu MK, Wesselink PR (2007b) The evaluation of removal of calcium hydroxide paste from an artificial standardized groove in the apical root canal using different irrigation methodologies. International Endodontic Journal 40, 52–7.

- Windley W 3rd, Ritter A, Trope M (2003) The effect of short-term calcium hydroxide treatment on dentin bond strengths to composite resin. Dental Traumatology 19, 79–84.