Minimization of Complications in Dental Treatment

Machine translation

Original article is written in RU language (link to read it) .

Clinicians cannot always be sure that their initial diagnosis and risk assessment will lead to the most predictable treatment. Functional diagnoses may not always be clear or neatly fit into one category. In this case, a strategy for managing dental treatment complications without increasing the risk of future problems for the patient is presented. It also demonstrates the principles of risk-based treatment planning, as well as the difficulties that may arise in trying to ensure a successful restorative treatment plan.

The technique for rehabilitating patients with occlusal disorders is presented in the webinar Parafunction and Tooth Wear: Treatment Methods.

Clinical Case Review

A 35-year-old man has complaints about the wear of the cutting edges of the upper central incisors, he was also dissatisfied with the aesthetics (photo 1 and 2).

His medical history revealed problems and symptoms that might be related to occlusal relationship disorders. He reported that correction had begun about 10 years earlier but was not completed, as he experienced increasing discomfort, headaches, tooth pain, and jaw problems during the process. He further mentioned that when clenching his teeth, he did not feel that they "all touched."

The patient also reported that over the past 5 years, he noticed his front teeth becoming thinner, experiencing chips, and discomfort while chewing foods such as bagels and hard bread, as well as chewing gum. He noted that sometimes he wakes up with an "awareness" of his teeth, and when he removes his night guard in the mornings, only the front teeth are in contact.

Diagnosis, Risk Assessment, and Periodontal Prognosis

The conducted radiographic study indicated a bone loss of less than 2 mm, and the depth of periodontal pockets did not exceed 4 mm. Minor recession and abrasion were present on the buccal surface of tooth 2.1, which were caused by anatomical features, not by disease. According to the classification of the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP), the diagnosis was early periodontitis (type II). Pocket depth — 3-4 mm, bleeding on probing may be present, localized recession, Grade I furcation involvement.

Risk: insignificant

Prognosis: good

Biomechanically: no caries or restoration defects were noted. The only findings were small amalgam restorations on the molars, which constituted less than one third of the tooth's occlusal surface. Several areas of erosion were also noted (photo 3).

Risk: insignificant

Prognosis: good

Functionally: on the vestibular surfaces of the anterior teeth of the lower jaw, there were facets of wear, and on the palatal surfaces of the anterior teeth of the upper jaw, various protrusions were noted. Minimal (less than 1 mm) palatal wear was observed (photo 4 and 5).

Facets of wear are accompanied by a limitation in the amplitude of chewing, which is associated with a moderate functional risk.

Risk: moderate

Prognosis: satisfactory

Average movement dynamics noted on both the upper and lower lips; the patient wanted to change the color of their teeth. Diastemas and tort-position were present.

Risk: moderate

Prognosis: satisfactory

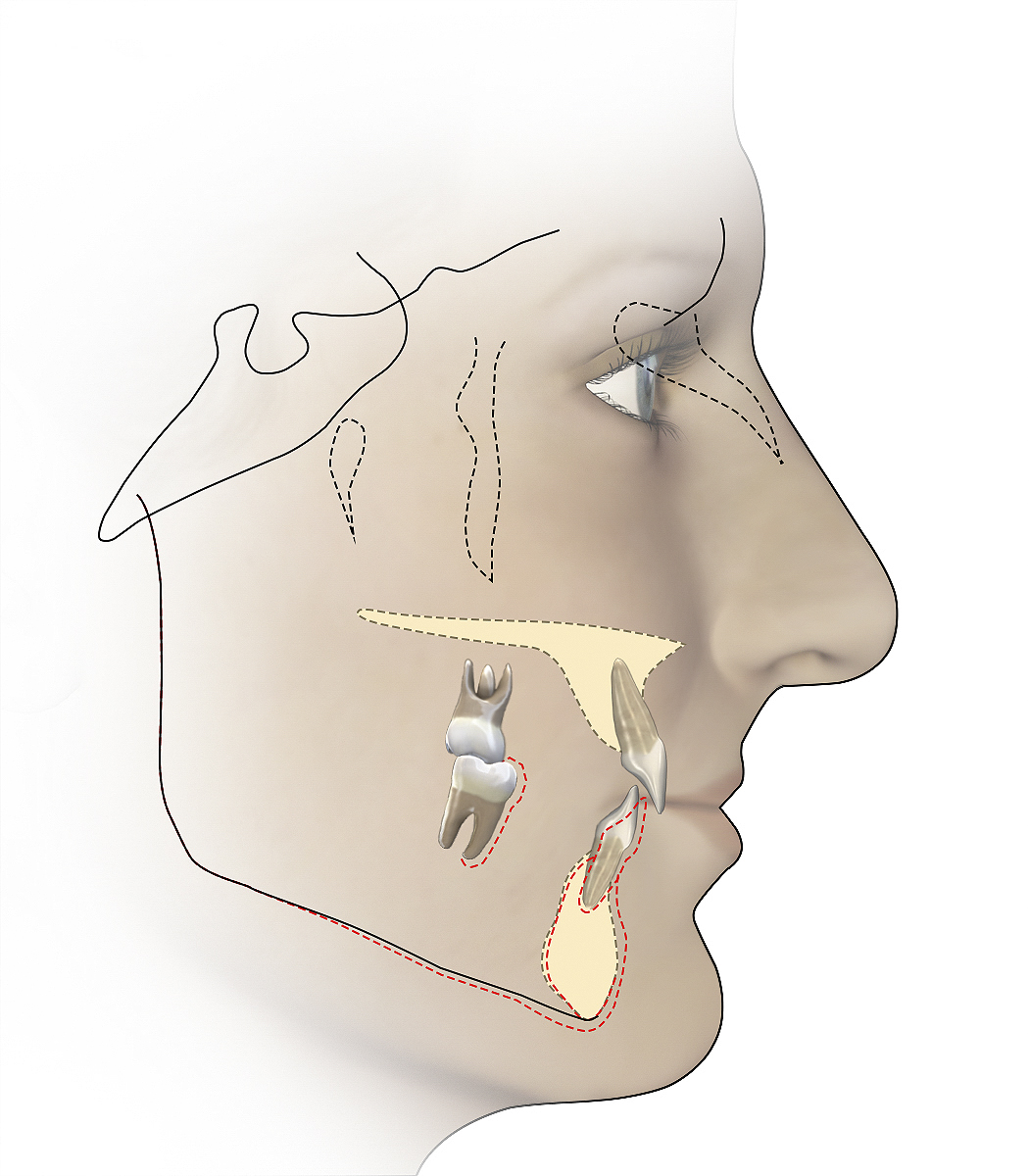

After deprogramming with the Kois Deprogrammer, the lower jaw moved forward, confirming the limitation in function. Traces on the deprogrammer platform indicated parafunction. Destructive wear of the anterior teeth (thinning) was not associated with parafunctions during lateral movements. Although the parafunction could not be completely eliminated, the active destruction of the incisors was the result of adaptation, typically observed with limited chewing amplitude.

The cephalometric record was completed before and after the implementation of the deprogramming protocol (photo 6).

Although the cephalometric radiograph did not diagnose or determine the direction of treatment, it was an important landmark for treatment and helped confirm the diagnosis. The position of the lower jaw after deprogramming was significantly forward compared to pre- and post-deprogramming. Additionally, the measurement from the upper central to SN (sella-nasion) was at 100 degrees, and the angle between them was 142 degrees, which was slightly off from the expected norms.

Treatment Plan

Considering the patient's diagnosis and the risk in the four main areas outlined above, various treatment options were carefully evaluated and selected with the patient's informed consent.

Phase 1: Orthodontic Therapy

The initial treatment consisted of orthodontic therapy to correct the tortuous position of the frontal teeth, extraction of the upper jaw incisors, and correction of the position of the lower frontal teeth. Although the position of the cutting edge of the lower front teeth was acceptable, the patient preferred to have them restored. Therefore, it was important to inform the orthodontist not to make any changes in the vertical plane. As a result of the treatment, a more favorable ratio of the front teeth was established, which corrected the limitations of the amplitude of movement. Sufficient inter-incisal space was preserved for post-orthodontic occlusal balancing, as well as for the restoration of the front teeth with minimal tooth preparation (photo 7).

Stage 2: Stabilization Period

The 6-month stabilization period was recommended after orthodontic treatment and before starting restorative procedures. During this stabilization period, the patient wore retainers.

Phase 3: Deprogramming and Occlusal Balancing

After stabilization, the patient wore a deprogrammer for 3 weeks. When the deprogramming was completed, there were no changes in the position of the lower jaw. This indicated that the orthodontic therapy had created more favorable conditions between the front teeth and had leveled the narrowing. It was now possible to perform occlusal balancing using the deprogramming device. Ultimately, the restoration of the front teeth and the worn tooth structure would be accomplished using veneers.

Stage 4: Occlusion Enhancement

The design of restorations on the palatal surface of the upper incisors was determined by the existing wear facets, which minimized further tissue reduction (photo 8).

The incisors' cusps remained untouched, and the vestibular and proximal preparations were mainly within the enamel limits. (photo 9 and 10).

A small gap between the upper front teeth, when they were smoothed labially in the orthodontic phase, required proximal preparation of the upper incisors. The spaces distal to them were not closed, as the patient agreed that they are not aesthetically significant.

Due to the average dynamics of the patient's lips, the risk of recession in the area of tooth 2.1 was assessed as a minor aesthetic issue. Therefore, the cervical areas were prepared to remain slightly supragingival and completely in enamel. Transparent porcelain constructions were used at the cervical level, which allowed preserving the relief reserve in accordance with the basic structure of the tooth. It then becomes almost invisible in the patient's smile and is an ideal way to restore the edges supragingivally in aesthetic areas.

The lower incisors required restoration of the cutting edges to reconnect with the cutting edges of the upper incisors and restore the normal ratio. Minimal preparation of the vestibular surface was required, while the final restoration recreates the cutting part to restore the tooth structure that was lost from wear. The cervical surfaces remained affected only in enamel, and proximal treatment was not required. The patient required restoration of the cutting edges of the lower incisors to cover the exposed dentin. The preparation was completed using a technique similar to that of the lower incisors.

All restorations were recorded using the total etching and bonding technique. After the fixation was completed, the dental arches were closed in the position of central occlusion. Using 200-µm articulation paper, the correction of the interrelationships of the dental arches was carried out. This helped improve the function on the palatal surfaces of the upper anterior teeth and establish a smooth sliding path.

Diagnosis and Treatment of an Unexpected Complication

Three months after the treatment was completed, the patient returned with a broken veneer on tooth 4.3 (photo 11).

He reported that the fracture occurred during sleep. The veneer was remade and secured with further polishing on the patient's right side to reduce friction. A similar fracture occurred again within the next 3 months, again during sleep.

The episodic nature of this patient's parafunction and the preoperative wear pattern on his dental arch served as a disguise for the presence of destructive parafunctional forces.

Thus, it is necessary to consider the existence of periodic parafunction, which represents an increased functional risk, even if the wear pattern on the teeth was associated with limited range of motion. Interestingly, the fractures occurred during sleep. This indicates a nocturnal sleep disorder, such as parafunction, rather than a daytime occlusal disorder or adaptation. The chip occurred only on the most at-risk tooth, which bore the load. However, this tooth was covered with a porcelain veneer, which could not cope with the parafunctional forces. The opposite palatal cusp received the load, where the enamel was undamaged. Since a small amount of enamel was prepared, the veneer, not the tooth, had an increased risk of fracture.

Front restorations and the dental arch ultimately required protection with a cap (photo 12).

Since wearing the night guard, lateral grooves have appeared on it, confirming the diagnosis of bruxism. Over the 9 years since the completion of treatment and wearing the cap, there have been no further failures in the restorations.

Reassessment of Diagnosis

This case demonstrates that in the event of unsuccessful restoration despite careful treatment planning considering risk, reassessment of the diagnosis and further analysis are crucial for ensuring long-term success. When faced with restoration chips, clinicians should consider episodic parafunctional forces and cap management. It is important to remember that patients may have more than one diagnosis; as in this case, they may have an occlusal disorder and a parafunctional disorder.

As of the time of publication, the risk of periodontal pathology remains insignificant and the prognosis is good. Dynamic observation continues with a 6-month interval. Biomechanical risks were not increased by orthodontic repositioning, which allowed for the placement of minimally invasive, enamel-supported restorations to replace the missing tooth structure. The functional risk during chewing was reduced with orthodontics. Destructive forces during sleep were controlled by wearing a night guard. The aesthetic risk was reduced using feldspathic veneers, which provide a semi-transparent restorative structure. It is easier to reproduce the natural appearance of teeth with a semi-transparent zone to hide the cervical margin.

Conclusion

This diagnostic and treatment approach led to the successful restoration of the patient's teeth (photos 13-15).

During the publication, the final restorations remained aesthetic and functional, without harming the oral cavity. The patient slept with a mouthguard, and after 9 years, there were no fractures or chips. Properly correcting the anomalies in the position of the teeth, caused by daytime chewing and nighttime grinding, the final result reduced the risk of recurrence, and a successful outcome is expected to be long-term.

About the prevention of pathological wear and the strategy for treating patients with bruxism in the webinar Bruxism and Pathological Wear: Relationship and Treatment Principles.

http://aegisdentalnetwork.com/

/public-service/media/default/184/77OOf_65312297d7ef3.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/478/KvUj4_671f55677a456.png)

/public-service/media/default/186/1Vv5n_653122c853165.jpg)