Reducing Carious Lesions During the First 4 Years of Life: An Interprofessional Approach

ABSTRACT

Background. Caries in Peruvian 0- through 3-year-olds is high. The dental profession should collaborate with nurses at mother and child health (MCH) clinics for reducing the disease. In this randomized clinical trial, the authors tested an integrated intervention program implemented by nurses and dentists. You have the opportunity to gather more in-depth information about treatment methods in pediatric dentistry in our course "Pediatric dentistry school".

Methods. The authors developed age-specific (0-3 years) oral healtherelated information and activity record cards and validated them for nurses to use after being educated about oral health issues and mouth inspection. The authors trained dentists in atraumatic restorative treatment. The active intervention group (AG) participated in the integrated intervention program, the passive intervention group (PG) received only the oral healtherelated information and activity record cards, and the control group (CG) received only a lecture. The examiners assessed caries status according to the Caries Assessment Spectrum and Treatment instrument. The authors used analysis of variance and the Tamhane method to analyze the data.

Results. The sample consisted of 368 children with a mean age of 3.1 years. The 3-year dropout percentage was 40.5%. The prevalence of cavitated dentin carious lesions was statistically significantly lower in the AG (10.0%, confidence interval [CI] 4.1 to 19.5) than in the PG (60.5%, CI 48.6 to 71.5) and CG (63.0%, CI 50.9 to 74.0) after 3 years (P < .001). Enamel carious lesions (62.9%) were most prevalent in the AG, whereas carious lesions were most prevalent in the PG (28.9%) and CG (32.9%).

Conclusions. Incorporation of specific oral health care activities into the existing MCH program, implemented by trained nurses and supported by health center dentists, reduced the burden of caries in 3-year-olds substantially.

Practical Implications. The oral health care professionals in Peru should collaborate with personnel of MCH clinics to curb caries in 0- through 3-year-olds.

INTRODUCTION

Early childhood is a crucial phase in a child’s physical, social, and emotional development. Proper development lays the foundation for the future health, academic success, and overall well-being of the child.[2] Oral diseases such as caries may cause pain and alter basic functions, such as feeding, sleeping, speech, and self-esteem, which threaten optimal development of the child’s capacities and may cause a suboptimal quality of life.[3]

Untreated dentin caries in primary teeth are ranked 10th among the most prevalent diseases affecting people worldwide.[4] As dentin carious lesion experience in the primary dentition is the most important predictor for carious lesion development in permanent first molars,[5,6] all oral healtherelated efforts should be directed at preventing carious lesion development in the first years of a child’s life. However, it appears that the dental profession alone cannot handle the carious lesion epidemic in children. It needs assistance from other professions that deal with the development of children. Because caries is considered a behavior or lifestyle disease, which, in essence, can be prevented, the dental profession should collaborate with educational and other health care professionals to curb the disease, particularly early childhood caries.

In most communities, a dental practitioner sees a young child after the manifestation of a symptom, usually painful caries. The appearance of caries shows that carious lesion prevention has failed and that treatment is needed. However, if preventive actions had been taken in the early part of the child’s life, symptoms such as caries or an abscess could have been avoided in most cases.

The best place for educating parents in implementing good oral health behaviors for their young children and themselves is the mother and child health (MCH) clinic, at which physicians and nurses work. Nurses are responsible for the administration of vaccines, counseling parents about nutrition and body hygiene, psychomotor development, and monitoring the overall development of the child. The oral health component can be introduced easily into the routine performance of nurses employed in those services if they are permitted and willing to do so.

This integrated approach is supported by the World Health Organization, which urges collaboration among health care professionals in achieving objectives in an interprofessional manner.[7] Outcomes from the 2017 World Health Organization summit suggested that children at the age of 3 years should be a new target population for epidemiologic studies.[8]

In our study, we investigated the effectiveness of an oral health promotion, prevention, and restoration program directed at newborns and their parents that is implemented by nurses and dentists employed at MCH clinics and fully integrated into their daily routines. The null hypothesis tested was that the prevalence and severity of carious lesions in 3-year-old children who had participated in the intervention program from birth were no different from results obtained from 2 other groups.

METHODS

Ethical approval

The institutional review board of the Dental School of San Martin de Porres University in Lima, Peru, issued ethical approval (Resolution 252-2013-D-FO-USMP). This randomized clinical trial (RCT) is registered at the Netherlands Trial Register (NTR 4510). Parents received an informed consent and a personal information registration form. We requested them to sign the form if they agreed to have their children participate in this 3-year RCT.

Study design

The sampling unit was the health care center, operating under the administration of the Ministry of Health in Lima, Peru, and situated in a low socioeconomic status district designated according to economic indicators used by the Peruvian National Institute of Statistics and Information.[9]The inclusion criterion was a well-functioning MCH clinic in a health care center. From a total of 10 eligible districts, we randomly selected 3 and randomly allocated them to the 3 study arms by using a software program (Easy Randomizer, Version 4.1, EASYRA1). These districts were geographically far apart from one another, reducing the risk of contamination during the longitudinal intervention. Each of the 3 districts had 1 health care center with an MCH clinic. We contacted mothers who had attended the MCH clinic with their newly born child between January and March 2015, informed them about the content of the study and invited them to participate in it. Those who signed the informed consent form had their baby included in the study.

Intervention program

The RCT consisted of 3 groups. These were an active intervention group (AG), a passive intervention group (PG), and a control group (CG).

The AG

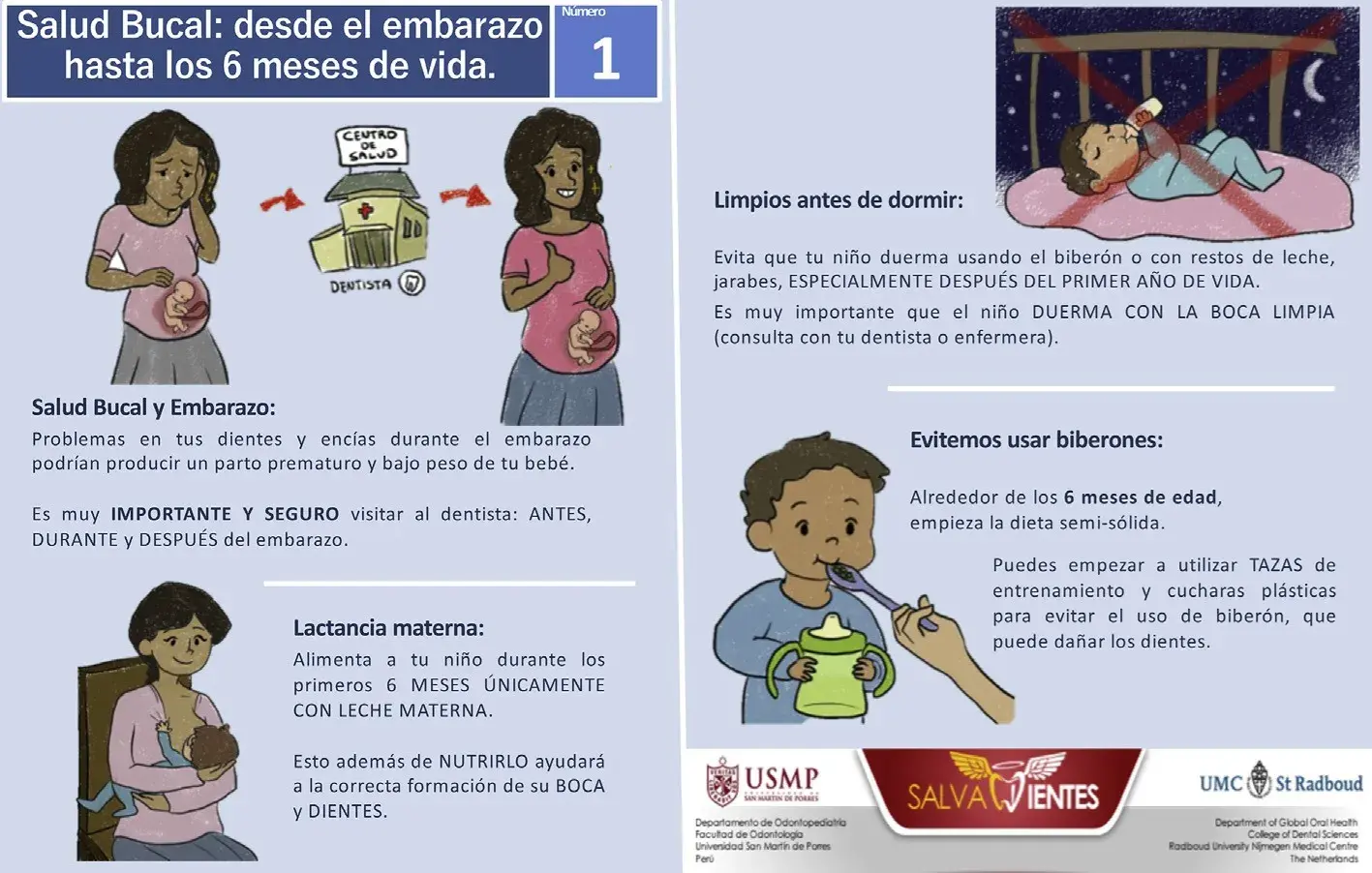

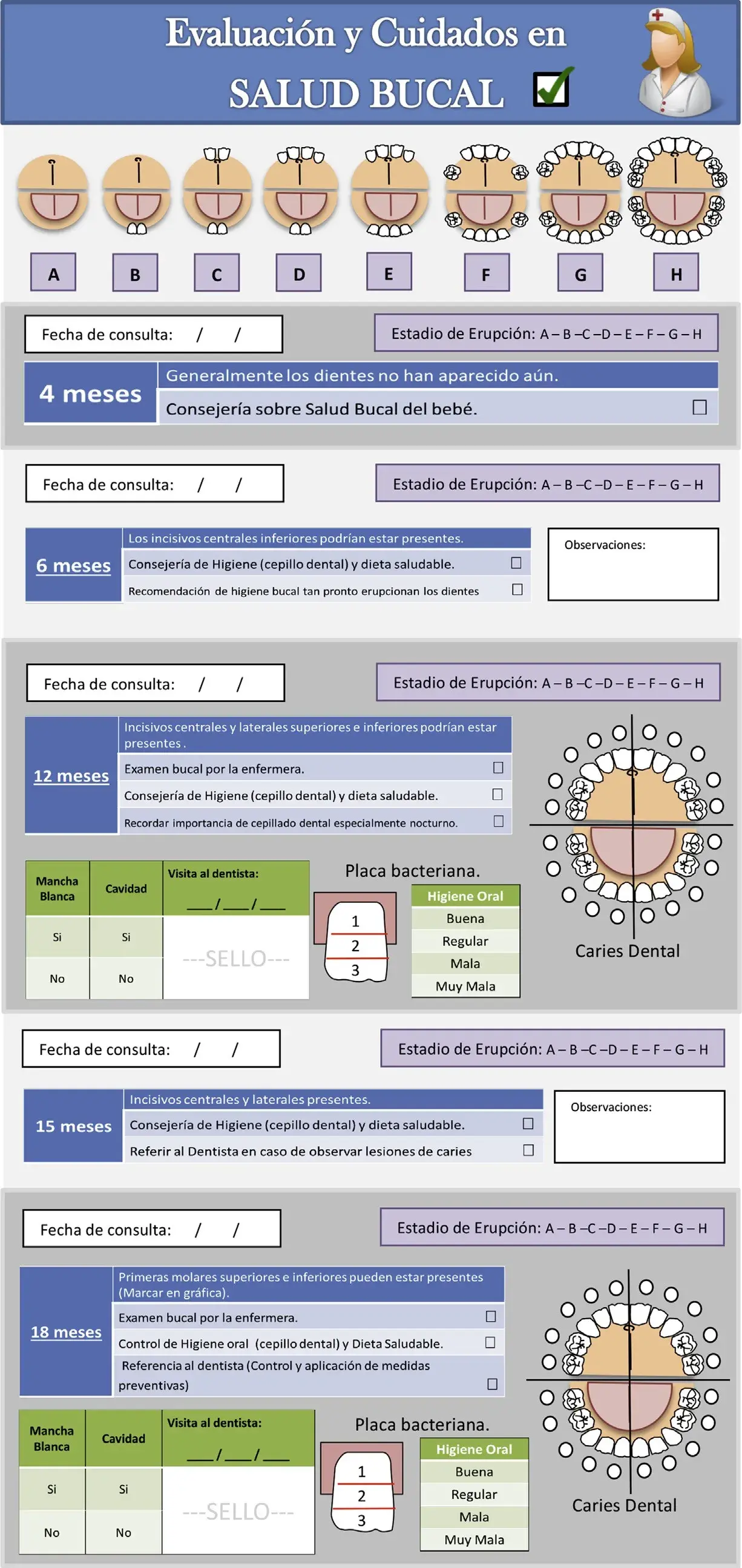

We developed and validated 3 oral health age-related information cards (leaflets) and delivered them to families.[10] These cards assisted the nurses when advising family members during regular child visits (Figure 1). In addition, we developed a time-related activity record card that assisted the nurses in the kinds of activities that need to be performed on a particular visit (Figure 2). We explained these cards and information about oral health to nurses at a training program of 4 90-minute sessions. The training included the concepts of caries prevention and early detection and identification of caries risk factors, followed by a workshop on mouth inspection, identification of abnormal signs on teeth and oral mucosal tissues, and how to use the information and record cards.

We asked the nurses to refer children who showed signs of a carious lesion to the health center dentists for further diagnosis and treatment. We trained these dentists in how to treat and examine young children and how to apply atraumatic restorative treatment (ART). Treatment usually consisted of fluoride varnish application (every 6 months or as needed) and provision of ART sealants and ART restorations, in addition to emphasizing self-care activities at home (reducing sugar consumption as much as possible, promoting a healthy diet, and toothbrushing with pediatric fluoride toothpaste and using good toothbrushing techniques).

The PG

Nurses received all printed materialsdinformation leaflets and record carddtogether with written instructions for using them. This approach is common practice in the delivery of educational materials from the Peruvian Ministry of Health. Health center dentists received the same training as did their colleagues from the AG. The main difference between the AG and the PG was that nurses received training in the former group and not in the latter.

The CG

Nurses received only a 45-minute lecture on the importance of oral health. Dentists did not receive education in ART. Nurses used the regular protocols stated by the ministry of health.

Figure 1. The oral health advisory card for infants from 6 through 12 months delivered to mothers who participated in the active and passive intervention groups.

Figure 1. The oral health advisory card for infants from 6 through 12 months delivered to mothers who participated in the active and passive intervention groups.

Figure 2. Activity record card for oral health guidance for nurses and dentists (same format as the vaccination card issued by the Peruvian Ministry of Health).

Figure 2. Activity record card for oral health guidance for nurses and dentists (same format as the vaccination card issued by the Peruvian Ministry of Health).

Oral examination

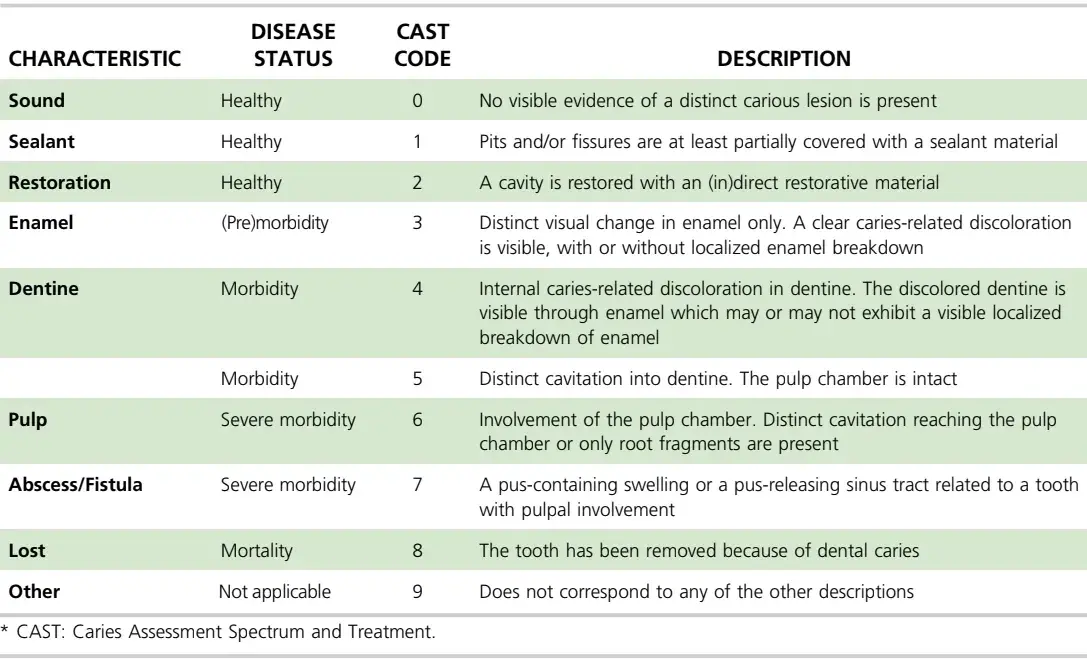

Two calibrated pediatric dentists assessed the caries status of the participating children by using the Caries Assessment Spectrum and Treatment (CAST) instrument (Table 1) on the premises of the 3 health centers.11 CAST involves using the epidemiologic concept of health and disease and considers treated surfaces with sealants and restorations as healthy. The CAST codes are ordered hierarchically from no carious lesion through a carious lesion in enamel and in dentin to pulp-involved and abscessed teeth and teeth missing due to caries.[12] The higher the code, the more severe the caries-related symptoms. CAST codes 0 through 2 and code 8 are excluded from the calculation of the prevalence of caries because they do not reflect active disease.

We trained examiners in using the CAST instrument, and a senior epidemiologist (J.E.F.) calibrated them. The training followed the recommendations of the CAST manual.13 The k co-efficient values for inter- and intraexaminer agreement for the 2 examiners at the end of the calibration sessions were 0.75 and 0.81, and 0.74 and 0.75, respectively.

Table 1. Codes, descriptions, and disease statuses of the hierarchically ordered CAST* epidemiologic instrument.[11]

The examiners performed the oral examination in the AG after 1, 2, and 3 years and in the PG and CG after 2 and 3 years. The mothers of the children in the study received the dates of the examinations via their cell phones. The examination dates also were written on posters attached to the health center front door 2 months in advance.

Before the oral examination, the children’s teeth were cleaned with a cloth or toothbrush, toothpaste, and floss (where needed). The examiner then examined the children’s teeth, with the children in the knee-to-knee position, by using a dental mirror, a Community Periodontal Index probe, gauze, and a battery-powered headlight (Energizer 3 LED, Energizer Holdings) in 1 of the health center rooms. The examiner used the Community Periodontal Index probe for removing any remaining plaque after toothbrushing and dried each tooth with gauze. The examiner’s voice was recorded on a digital device, and the transcription was transferred to a spreadsheet (Excel, Microsoft). The device measured the examination time.

Both examiners reexamined 6 patients (528 surfaces) during the clinical examination. The interexaminer consistency test result was a k coefficient of 0.84.

Further details about caries prevention and treatment on children are accessible for you to learn on our website in Pediatric Dentistry section.

Statistical analyses

On the basis of reducing the prevalence of early childhood caries (65.5%14) at 3 years by 26% in the AG, an a of 5% and a power of 0.8, the sample size was calculated to be 54 participants per group. Allowing for a dropout rate of 10% per year, the sample size per arm was 70 participants.

An experienced statistician (E.B.) analyzed the data by using a statistical software package (SPSS Version 24.0, IBM). The prevalence of carious lesions (dental caries) is calculated using CAST codes 4-7.

CAST codes 3-7 are used for calculating the prevalence of enamel and dentin carious lesions combined. Reporting the caries situation using the CAST instrument includes the maximum (max) CAST code per tooth (the highest code among the codes of all surfaces on an examined tooth=MaxCASTtooth); the max CAST code per subject (the highest code among the codes of all teeth examined in a subject=MaxCASTsubject); and the CAST severity score.[15] The last-mentioned score was obtained by first selecting the max CAST code per tooth, which was then applied to Formula F1 as shown:

F1 = 0.25*CAST3 + 1*CAST4 + 2*CAST5 + 4*CAST6 + 5*CAST7 + 6*CAST8

in which numbers (before the *) denote the weight of every CAST code to perform the calculation. Codes 0, 1 and 2 are not included, as they are considered healthy situations. The highest weight is ascribed to code 8, which indicates mortality (extraction of a tooth due to caries), considered the poorest condition of the caries spectrum. CAST scores also can be presented according to disease status: healthy, premorbidity, morbidity, severe morbidity, and mortality (Table 1). A cumulative maximum CAST code per participant is calculated by using the highest CAST code within a person. We calculated a count of decayed, missing, filled teeth (dmft) from data collected by using the CAST instrument.

We compared the results of this RCT with those of a cross-sectional (CS) study in 3-year-olds who participated the MCH program in the 3 respective health centers before the start of the RCT. These results served as a CS reference.

We compared the CAST severity scores across the 3 groups by using analysis of variance and performed post hoc analyses according to the Tamhane method, which is suitable if variances between groups are different. We set a significant difference at P < .05.

RESULTS

Disposition of participants

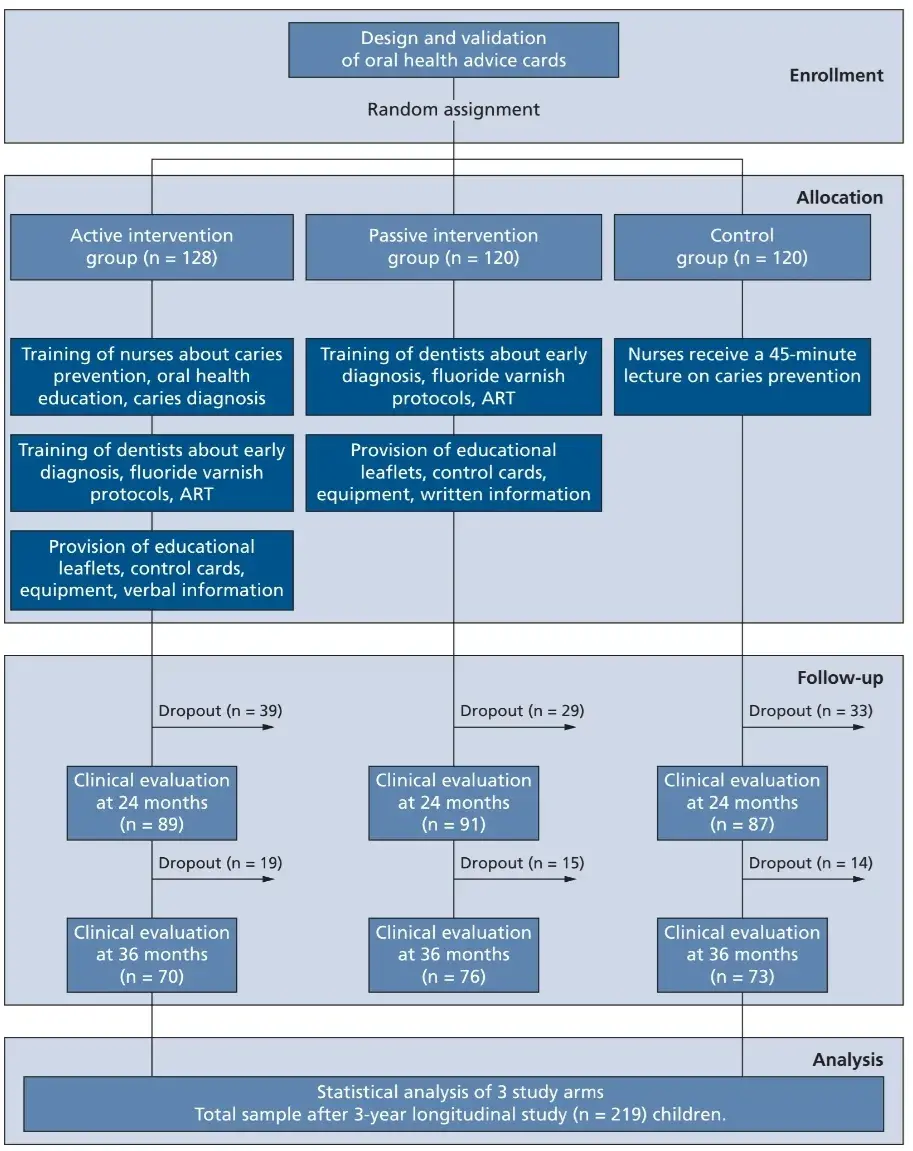

Figure 3 presents the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram. The initial sample consisted of 368 participants (50.7% male) who were a mean (standard deviation) of 3.1 (0.2) years of age at 3-year evaluation. The dropout rates after 3 years were 45.3%, 36.7%, and 39.2% for the AG, PG, and CG, respectively. The mean times used for examining the children were 61.6, 65.4, and 58.1 seconds for the AG, PG, and CG, respectively.

Figure 3. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flowchart.16 Reasons for dropouts were that participants could not be reached by telephone or at their home addresses. ART: Atraumatic restorative treatment.

Figure 3. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flowchart.16 Reasons for dropouts were that participants could not be reached by telephone or at their home addresses. ART: Atraumatic restorative treatment.

Effectiveness of the intervention program

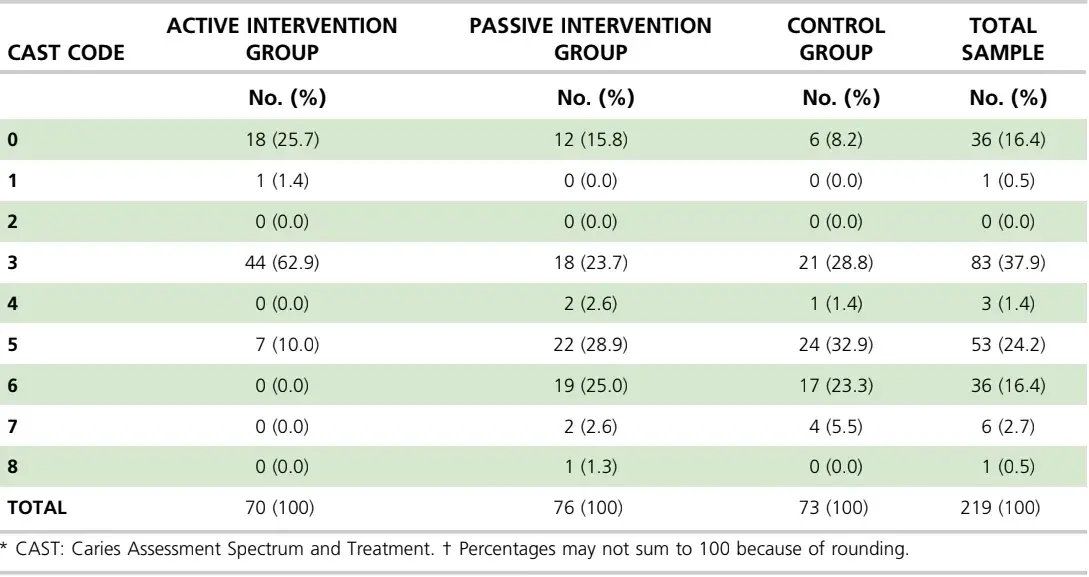

Table 2 presents the frequency distribution of maximum CAST codes per child according to sample and intervention group. The most frequently scored maximum CAST code per child was code 3 (enamel carious lesion) in the AG (62.9%) and code 5 (dentin carious lesions) in the PG (28.9%) and in the CG (32.9%). A healthy dentition was present in 27.1% of the children in the AG and in 15.8% in the PG and 8.2% in the CG at 3 years. One tooth had been extracted in the PG.

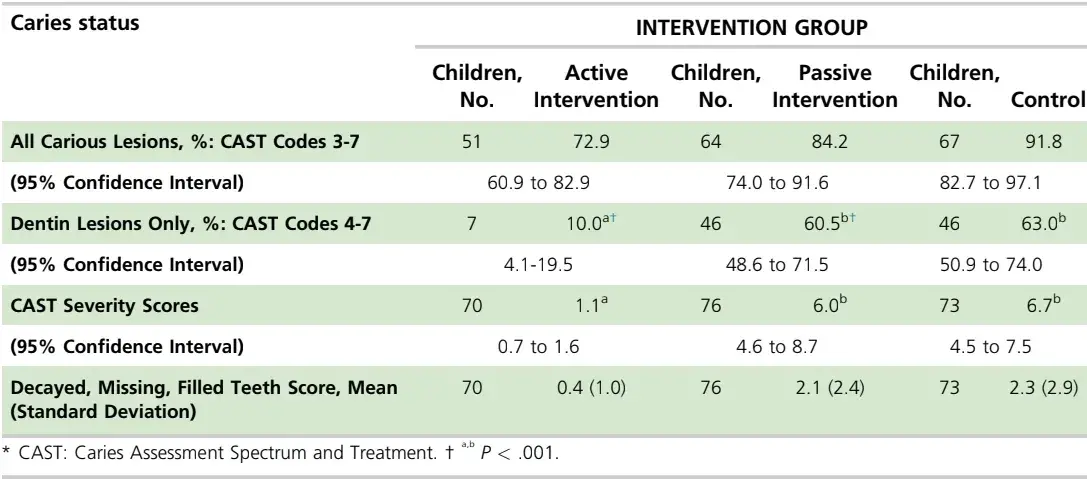

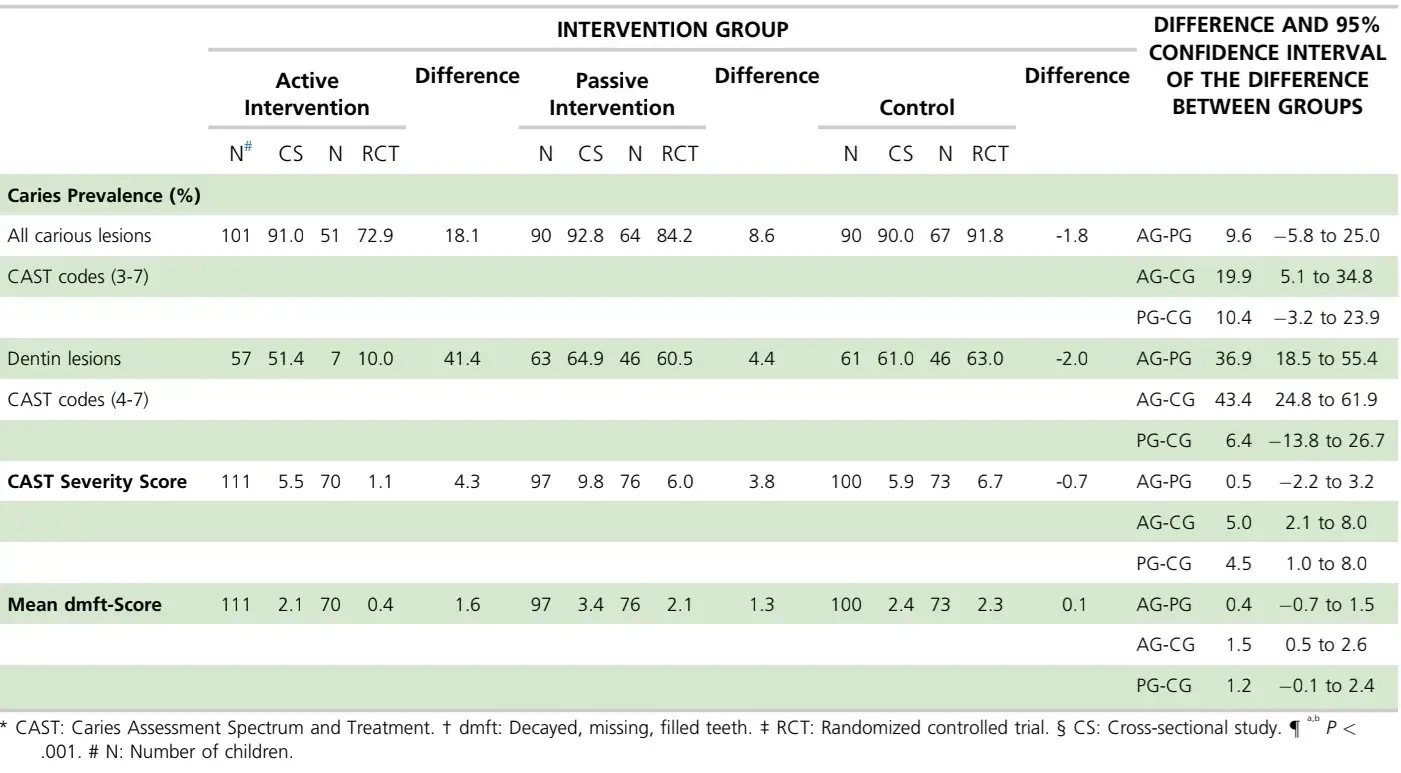

Table 3 shows the prevalence of carious lesions, CAST severity scores, and mean dmft scores according to intervention group. The prevalence of cavitated dentin carious lesions was statistically significantly lower in the AG (10.0%) than in the PG (60.5%) and CG (63.0%; (P < .001). The CAST severity score was also statistically significantly lower in the AG (1.1) than in the other 2 groups (PG ¼ 6.0 and CG ¼ 6.7; P < .001).

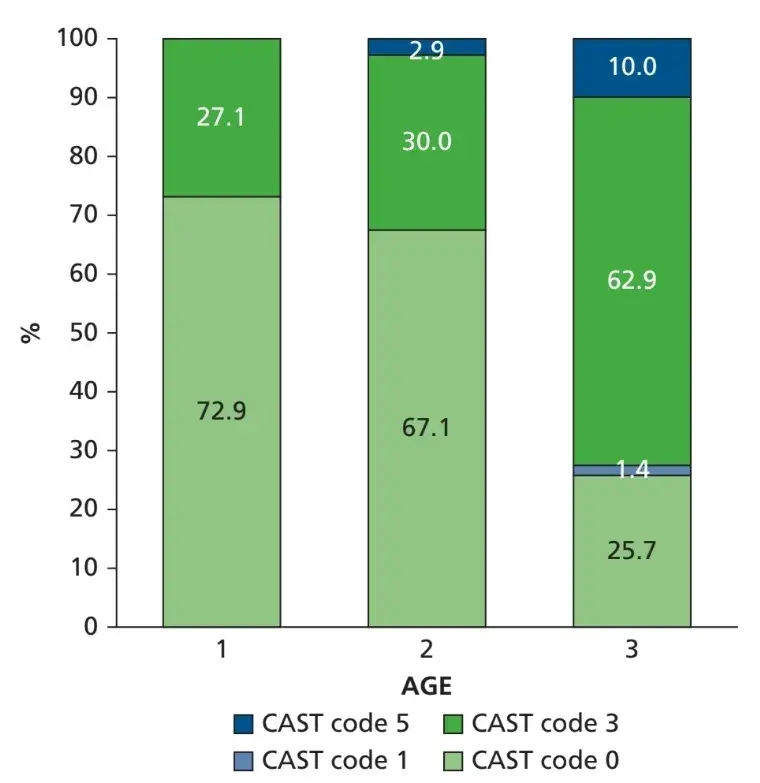

Figure 4 presents the frequency distribution of maximum CAST code per child in the AG according to year of examination. Enamel carious lesions occurred at year 1 and cavitated dentin carious lesions at year 2. One ART sealant had been placed at year 3 but no ART restorations at the time of examination.

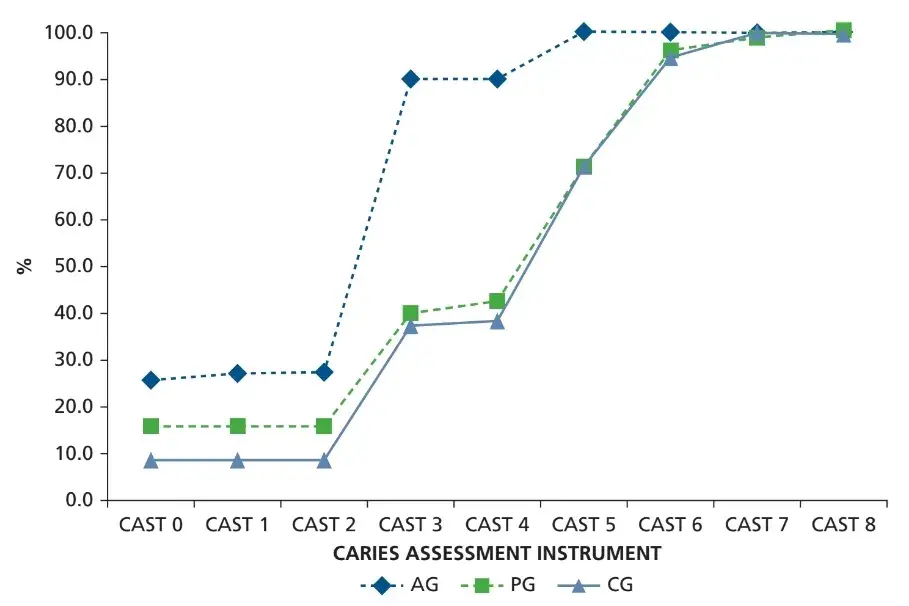

Figure 5 shows the cumulative frequency distribution of maximum CAST code per child for the AG, PG, and CG. The higher the curve expands to the left, the healthier the children are. The line for the AG depicts clearly a healthier state of caries among the children than do the lines for the other 2 groups. The burden of dentin carious lesions was lowest in the AG, but the children in this group had the highest prevalence of carious lesions in enamel.

Table 2. Frequency distribution of maximum CAST* code according to child per intervention group among 3-year-olds.

Table 3. Prevalence of carious lesions (%), CAST* severity scores and 95% confidence interval, and mean decayed, missing, and filled teeth scores of 3-year olds by intervention group in the randomized controlled trial.

Figure 4. Percentage distribution of maximum Caries Assessment Spectrum and Treatment (CAST) code per child from children in the active intervention group (n ¼ 70) at 1-, 2-, and 3-year follow-up examinations.

Figure 4. Percentage distribution of maximum Caries Assessment Spectrum and Treatment (CAST) code per child from children in the active intervention group (n ¼ 70) at 1-, 2-, and 3-year follow-up examinations.

Figure 5. Distribution of cumulative percentages of maximum Caries Assessment Spectrum and Treatment (CAST) code per child for the 3-year-old children according to study group: active intervention group (AG), passive intervention group (PG), and control group (CG).

Figure 5. Distribution of cumulative percentages of maximum Caries Assessment Spectrum and Treatment (CAST) code per child for the 3-year-old children according to study group: active intervention group (AG), passive intervention group (PG), and control group (CG).

Comparison with the CS study

Table 4 presents the difference in carious lesion prevalence percentages, CAST severity scores, and mean dmft scores between this RCT and the previously conducted CS study. Compared with that in the AG, the dentin carious lesion prevalence was statistically significantly lower in the PG and the CG, whereas the CAST severity score and mean dmft score were statistically significantly lower in the CG.

Table 4. Carious lesion prevalence (%), CAST* severity scores, mean dmft† scores and the difference and the 95% confidence interval of the difference between the current RCT‡ and the related prior CS§14 study of 3-year olds by intervention group.

DISCUSSION

We rejected the null hypothesis. Children who participated in the active intervention program from birth had significantly lower values for caries prevalence and caries severity at 3 years than did their peers in the control groups. Notwithstanding the substantial difference in values between AG and the other 2 groups, the fact that 27.1% of the children from the AG had developed at least 1 enamel carious lesion at age 1 year and 10.0% had developed a cavitated dentin carious lesion at age 3 years indicates that the intervention program failed to prevent dentin carious lesion development. The findings of this RCT are in line with those obtained from the reference CS study. However, they also reveal that the differences between the groups are related predominantly to the presence of dentin carious lesions.

With the inclusion of enamel carious lesions in the AG, which increased the carious prevalence from 10.0% (dentin only) to 72.9%, the significant difference with the PG group disappeared. In fact, the prevalence of enamel carious lesions in all groups was relatively high, which might be due to the low socioeconomic strata to which the participants belonged and to the low educational level of their parents. Both factors have been associated with the development of caries in preschool-aged children and are considered determinants of oral health behavior.[17,18] Therefore, it is fair to conclude that the intervention program reduced the increase in carious lesion development rate in the first 3 years of life. Therefore, it needs to be evaluated and improved because these values are still too high for a disease that is, in essence, preventable.

We encountered a few difficulties with the intervention program. For example, many trained nurses were transferred to other offices after 2 years and replaced by nurses who were uninformed about the intervention program. Only after these nurses were trained could the intervention program be reimplemented. To what extent the interruption influenced the results in the AG group is unknown. We monitored the intervention program by keeping records of children who were referred to the health center dentists. Not only the study children but all children attending the MCH clinic in the AG health care center who were in need of oral health care were referred to the dental clinic. The percentage of children, up to of 3 years of age, who attended the dental clinic 1 year before the start of the intervention program (CS study) was 9.6%, which increased to 64.6% after 3 years. This increase in dental attendance can be attributed only to the implementation of the intervention program. A properly conducted evaluation that includes the views of the mothers will yield action points for further improving the running of the program and, subsequently, the oral health of the children.

Results from the CS study showed that the dropout percentage of the present study could be higher than the 30% envisaged in the sample size calculation. In addition, law in Peru requires researchers to include participants in a study if they are eligible. These 2 reasons explain the larger study sample size than calculated. Considering the high difference in study outcomes between the AG and the other 2 groups, we do not think that the larger sample size has influenced the results substantially. The number of children that dropped out in the 3 groups was substantial. We do not know why parents did not attended the MCH clinic. As the study children came from low socio-economic status areas with similar backgrounds, we assume that the dropped-out children did not belong to a specific group within the local society, and as such have not influenced the study outcomes significantly.

The results of the present study are in line with those from a related oral health intervention program for pregnant mothers and their children.19 Although the investigators performed the study at a dental school, 4-year-old children who attended the dental clinic for oral health advice and tailor-made preventive care on average 2.8 times per year had a dentin carious lesion prevalence of 9% and a mean dmft score of 0.25, whereas the 4-year-olds in the control group, whose mothers did not accept the invitation to participate in the program, had a dentin carious lesion prevalence of 81% and a mean dmft score of 4.12. The mean dmft score for the children in the AG in the present study was 0.4. The PG represented the way the Peruvian Ministry of Health disseminates recommendations to its workforce. Three years before the study started, the Ministry of Health issued recommendations that urged health center employees to give attention to the oral health of infants free of charge. In the present study, we obtained evidence that the manner of informing these employees should be more effective.

The strength of the study is that in a previous study we had asked nurses in Lima, through a structured questionnaire, whether they were willing to provide oral health advice and perform mouth inspection.[20] Overwhelmingly, the nurses responded positively, on the provision that they received proper training in oral health care. Together with the development of a validated oral health advisory card for mothers and a record card for assisting nurses during oral health consultations developed in line with the common growth card in use in all health centers, this outcome has contributed to the lower carious lesion burden in children from the AG compared with those in the other 2 groups.

We consider the internal validity of the study substantial, and we think that the active intervention program has the potential to be used in other health centers in Lima. Although MCH clinics are in operation in most countries in the world, a dental clinic is not usually available in the same building, and, if it is available, its oral health care services may not be free of charge, which implies that the external validity of our study may be considered low. Nevertheless, trying to keep healthy teeth healthy from birth through cooperation with health center employees should be attempted in such MCH clinics.

CONCLUSIONS

Incorporation of oral health care into the existing MCH program, implemented by trained nurses and supported by health center dentists, reduced the burden of caries in 3-year-olds.

There are additional information about actual treatment protocols of caries and non-caries lesions on children that you can obtain on our course "WHAT’S NEW in pediatric dentistry".

List of authors:

Rita S. Villena, Eraldo Pesaressi, Jo E. Frencken

References

Irwin LG, Siddiqi A, Hertzman C. Early Child Development: A Powerful Equalizer. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007.

VanLandeghem K, Curtis D, Abrams M. Reasons and Strategies for Strengthening Childhood Development Services in the Healthcare System. Portland, ME: National Academy for State Health Policy; 2002.

Leal SC, Bronkhorst EM, Frencken JE. Untreated cavitated dentine lesions: impact on children’s quality of life. Caries Res. 2012;46(2):102-106.

Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res. 2013;92(7):592-597.

Skeie MS, Raadal M, Strand GV, Espelid I. The relationship between caries in the primary dentition at 5 years of age and permanent dentition at 10 years of age: a longitudinal study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2006;16(3):152-160.

Vallejos-Sanchez AA, Medina-Solis CE, Casanova-Rosado JF, Maupomé G, Minaya-Sánchez M, Pérez-Olivares S. Caries increment in the permanent dentition of Mexican children in relation to prior caries experience on permanent and primary dentitions. J Dent. 2006;34(9): 709-715.

World Health Organization. Framework for Action in Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

Phantumvanit P, Makino Y, Ogawa H, et al. WHO global consultation on public health intervention against early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46(3):280-287.

Peruvian National Institute of Statistics and Information (INEI). Microdatos.

Pesaressi E, Villena RS, Frencken JE. Impact of oral health advices and illustrations card for use in mother-and-child health clinics: face and content validity. Br J Med Med Res. 2015;7(9):723-731.

de Souza AL, van der Sanden WJ, Leal SC, Frencken JE. The Caries Assessment Spectrum and Treatment (CAST) index: face and content validation. Int Dent J. 2012;62(5):270-276.

Leal SC, Ribeiro APD, Frencken JE. Caries Assessment Spectrum and Treatment (CAST): a novel epidemiological instrument. Caries Res. 2017;51(5):500-506.

Frencken JE, de Souza AL, Bronkhorst EM, et al. Manual CAST: Caries Assessment and Treatment. Nijmegen, The Netherlands: Ipskamp Drukkers; 2015:47.

Villena Sarmiento R, Pachas Barrionuevo F, Sanchez Huaman Y, Carrasco Loyola M. Prevalence of early childhood caries in children under 6 years old, living in marginal communities in the north of Lima [in Spanish]. Rev Estomatol Hered. 2011;21(2): 79-86.

Ribeiro APD, Maciel IP, de Souza Hilgert AL. Caries assessment spectrum treatment: the severity score. Int Dent J. 2018;68(2):84-90.

Hopewell S, Hirst A, Collins GS, Mallett S, Yu LM, Altman DG. Reporting of participant flow diagrams in published reports of randomized trials. Trials. 2011;12:253.

Harris R, Nicoll AD, Adair PM, Pine CM. Risk factors for dental caries in young children: a systematic review of the literature. Community Dent. 2004;21(1): 71-85.

Leong PM, Gussy MG, Barrow SY, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Waters E. A systematic review of risk factors during the first year of life for early childhood caries. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2013;23(4):235-250.

Medeiros PBV, Otero SAM, Frencken JE, Bronkhorst EM, Leal SC. Effectiveness of an oral health program for mothers and their infants. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2015;25(1):29-34.

Pesaressi E, Villena RS, van der Sanden WJM, Mulder J, Frencken JE. Barriers to adopting and implementing an oral health programme for managing early childhood caries through primary health care providers in Lima, Peru. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:17.