Study of skeletal changes in individuals with anterior open bite treated with JFO

ABSTRACT

Anterior Open Bite (AOB) is a type of malocclusion that promotes severe esthetic aesthetic and functional impairment. Its etiology is multifactorial and may involve several etiological factors, such as deleterious oral habits, hypertrophic tonsils, mouth breathing, dental ankylosis and eruption abnormalities either associated with genetic factors or not. AOB is one of the most challenging treatments in any treatment protocol. A retrospective study of 21 patients with anterior open bite treated with Jaw Functional Orthopedics (JFO) with improvement in overbite was conducted with the aim of understanding mandibular behavior during the treatment. Using SPSS 11.0, using Shapiro-Wilk test all variables showed Normal distribution (𝑝 > 0.05), in the comparison between the means at T0 and T1, the t-test for paired samples was used. In order to verify whether cooperative patients had better results than the non-cooperative group, a variable was created. For all tests, a significance level of 5 % was used. A weak statistical correlation (𝑃 ൏ 0,1) was found for Bimler’s Factor 8. Change resulted from AOB treatment with FOA in a short time. There was no statistical correlation of Bimler’s Factor 8 when cooperative patients were compared with the non-cooperative group. It could be concluded that in the studied sample there was a weak correlation between overbite improvement during AOB treatment with JFO and mandibular rotation. Further studies are necessary to understand the skeletal behavior of the maxillary bones in the treatment of AOB.

You have the opportunity to gather more in-depth information about open bite treatment in our website.

INTRODUCTION

Anterior Open Bite (AOB) is a type of malocclusion that promotes severe esthetic and functional impairment. The majority of authors agree that the etiology of AOB is multifactorial and may involve several etiological factors, such as deleterious oral habits, hypertrophic tonsils, mouth breathing, dental ankylosis and abnormalities in the tooth eruption process either associated with genetic factors, or not. AOB is one of the most challenging treatments for Jaw Functional Orthopedics (JFO), mechanical Orthopedics, orthodontics, and orthognathic surgery [1, 2].

However, there is little consensus about best age to treat, treatment protocol, retention period, and even about the definition of malocclusion. According to Rijpstra and Lisson [1] the only aspect about which there is agreement, is the high level of difficulty of treatment. When the Parafunctional etiology is not accompanied by skeletal etiology, this results in a simpler treatment, even with the occurrence of partial or total self-correction, depending on the age at which the parafunction is eliminated [3].

Simões [4] has reported that when craniofacial growth deformation caused by AOB surpassed normal growth standards, for instance, goniac angle greater than 130o when measured using Capitulare (center of the condyle), Gonion and Menton, or greater than 135o when using Articulare (cephalometric point – intersection of the posterior border of mandible ramus with the sphenoid bone), Gonion and Menton; this would increase the possibility of surgical treatment being the only possible treatment. The above-mentioned author added other parameters, such as those in cases when the inferior goniac angle reported by Jarabak was equal to or greater than 76o , and the individual had a broken protrusion movement. In cases such as these, the author recommended the use of both the Articular Compass cephalometry and the skeletal tracing to verify whether the non-surgical treatment protocol would be an option and the location tracing to position the frontal accessories in the Functional Orthopedic Appliance (FOA) if non-surgical treatment were available [5].

Many dental and/or skeletal changes have been reported based mainly on the treatment protocol used. Diminished anterior facial height occurred after treatment with cervical headgear due to a significant counter clockwise rotation of the mandible, and clockwise rotation and distal displacement of the maxilla [6]. Use of Quad Helix with crib generated a downward bodily rotation of the maxilla that contributed to correction of AOB.[7] Use of promoted a counter clockwise rotation in the mandibular plane, intrusion of mandibular molars e extrusion of maxillary incisors [8-10], while another study reported that using Invisalign the primary mechanism is incisor movement. [9] Correction of anterior open bite either with non-extraction or extractions with continuous arch wires and vertical anterior elastics will upright the mandibular posterior teeth. [11] Significant dental and skeletal changes were observed after treatment. Posterior build-ups in adults promotes molar intrusion, extrusion of mandibular and maxillary incisors and the mandibular plane angle showed a closure with decrease in anterior facial height [12,13]. Use of a surgical protocol led to rotation of the mandible, maxilla or both as it is a uni or bimaxillary protocol and some dento-alveolar compensation was reported [14, 15]. Soares and Santiago Jr. [16] reported the clinical efficacy of JFO to improve the overbite in AOB treatment with a 𝑃 = 0.003. But there is still no data available about the skeletal behavior due to FOA. The aim of this study was to investigate the behavior of the mandible by means of Bimler’s factor 8.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

In a universe of 257 patients, who underwent treatment at the clinic of the JOF specialization course of the ABOMG – Muriaé section, 47 patients (18.3 %) had anterior open bite. The sample of this investigation was composed of 21 of these patients who underwent a second teleradiograph exam after a period of 16 to 18 months of treatment. Of these, 6 patients (28.6 %) were males and 15 (71.4 %) females, with age ranging from 4 years and 11 months to 25 years and 3 months, with mean age 12 years and 1 month. The inclusion criteria were absence of anterior guide during protrusive movement of the mandible. All the legal tutors of the patients signed the Term of Free and Informed Consent.

A Lateral teleradiograph was requested for each individual before treatment for the purposes of diagnosis, prognostic and treatment assessment (T0) and after 15 months of treatment another lateral teleradiograph (T1) was requested to assess treatment evolution. The exam was performed in a period of between 16 and 18 months of treatment. The exams were performed by the same radiology technician on the same X ray device.

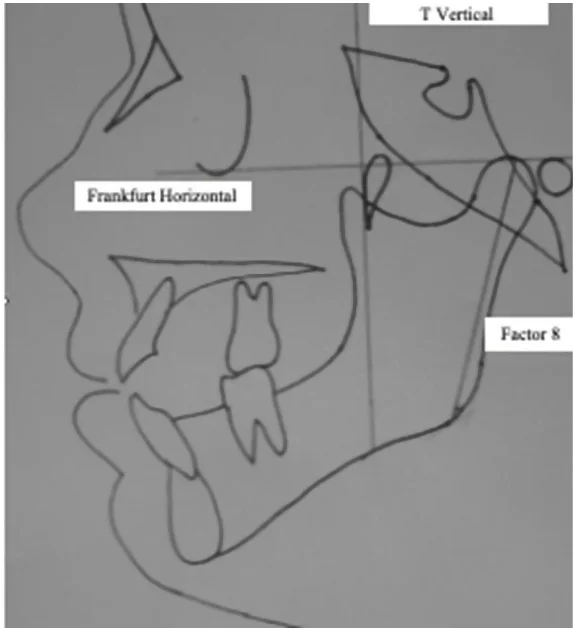

To study the behavior of mandible during AOB treatment, Bimler’s cephalometric analysis was used. Bimler defined 10 angular measurements, which he denominated Factors, and enumerated these factors from 1 to 10. The following cephalometric points were traced on the teleradiographs at T0 and T1: Orbitale (Or), Porion (Po), Tuber (T), Capitulare (C) and Gonion (G). From these cephalometric points the following planes were drawn Frankfurt Horizontal, T Vertical and Factor 8. Factor 8, a line that joins the center of the condyle represented by point C (Capitulare) to point G (Gonion) (Fig. 1), shows the mandibular flexion; that is to say, the degree of mandibular closure [4] was used to investigate the behavior of the mandible in AOB treatment. The tracings were made twice in each teleradiograph by the same investigator and checked separately by the other two.

Fig. 1. Simplified Bimler Cephalometry showing Factor 8

Fig. 1. Simplified Bimler Cephalometry showing Factor 8

Monthly clinical behavior of the dental overbite was measured with a digital pachymeter Litz Professional, 6 in/15 cm (Germany). In Fig. 2 clinical behavior of the overbite may be observed. In Figs. 2a and 2b AOB total closure and 2c and 2d AOB partial closure with a significant improvement in overbite.

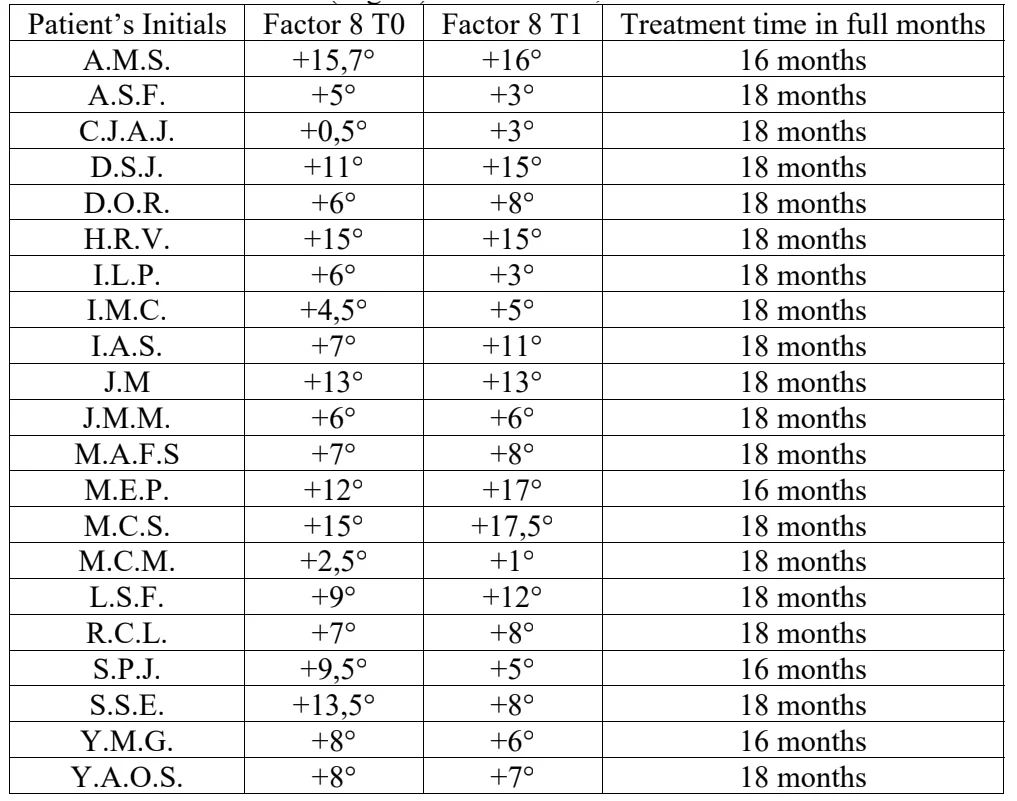

All individuals were treated with bioelastic FOA [4, 5], more specifically with Simões Network 2 (Simões Network 2 – Tongue Maintainer Model), SN3 (Simões Network 3 –Lower Winglets Model), SN6 (Simões Network 6 – Special Pad Model) [4] constructed according to Santiago Jr and Santiago instructions [17]. The behavior of Factor 8 in AOB treatment with FOA may be observed in Table 1.

Fig. 2. Examples of improvement in overbite with JFO treatment. a) Patient M.E.P. prior to treatment, b) result after 16 months of use of FOA with total closure of the open bite. c) Patient D.O.R. prior to treatment and d) after 18 months of use of FOA with partial closure of the open bite

Fig. 2. Examples of improvement in overbite with JFO treatment. a) Patient M.E.P. prior to treatment, b) result after 16 months of use of FOA with total closure of the open bite. c) Patient D.O.R. prior to treatment and d) after 18 months of use of FOA with partial closure of the open bite

Table 1. Factor 8 (degree) in T0 and T1, treatment time with JFO

RESULTS

SPSS 11.0 was used in statistical analyses. The assumption of normality was verified by the Shapiro-Wils test. As all variables showed approximately Normal distribution (𝑝 > 0.05), in the comparison between the means at T0 and T1; the t-test was used for paired samples. In order to verify whether cooperative patients had better results than the non-cooperative group, a variable was created, which expressed the difference (in degrees) between the result of T1 Rx and the result of T0 Rx.

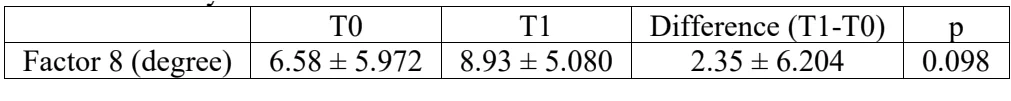

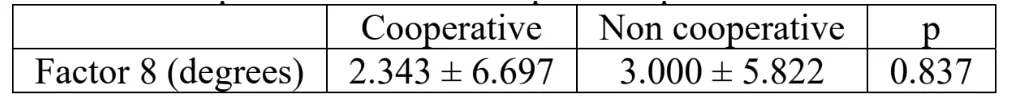

For all tests, a significance level of 5 % was used. A weak statistical correlation (𝑃 < 0,1) was found for Bimler’s Factor 8. Change resulted from AOB treatment with FOA in a short time (Table 2). showing that – at least – in the short-term treatment, improvement in overbite achieved by AOB treatment with JFO was not mainly due to increase in mandibular flexure. To check whether engagement in treatment could have an influence on these results. A comparison of the behavior of Bimler’s Factor 8 was made between cooperative and non-cooperative patients and no statistical correlation was found (𝑃 = 0,837) as may be seen in Table 3.

Table 2. Statistical analysis between T0 and T1 of Factor 8 behavior in AOB treatment with JFO

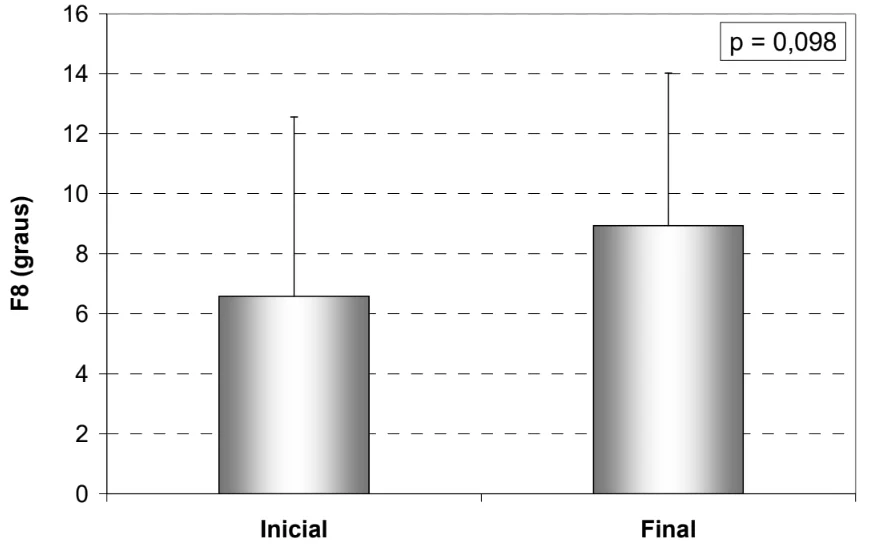

Fig. 3. Mean and Standard deviation of Factor 8 (degree) at T0 and T1

Fig. 3. Mean and Standard deviation of Factor 8 (degree) at T0 and T1

Table 3. Comparison between cooperative and non-cooperative patients. Data in mean ± standard deviation

DISCUSSION

Mandibular and/or maxillary rotation during AOB treatment has been reported in the literature. Use of orthodontic aligners promoted mandibular rotation during AOB treatment due to molar intrusion [8-10]. Since the FOA appliances used in the treatment of this sample did not promote molar intrusion this may be a reason why mandibular rotation was only weakly correlated with JFO treatment of AOB. Another reason may be related to relative treatment time. Since the mean treatment time of AOB with JFO takes about 36 months (excluded here were AOB malocclusion classified as skeletal [3, 4]) and treatment time with orthodontic aligners rarely exceed 12/15 months it would be useful to investigate the mandibular rotation achieved in AOB treatment with JFO after a 36-month period.

With the orthognathic surgical treatment protocol for anterior open bite(?), mandibular and maxillary rotation was observed [14, 15] depending on whether the surgical procedure was performed in one or both maxillary bones. The same rationale relative to above-mentioned treatment can be used when comparing mandibular rotation and results in the sample previously described with those of orthognathic surgery.

Mandibular rotation using build ups on molars has been described [12, 13]. According to the authors the build ups created a fulcrum and the mandible rotated, approaching the anterior region thereby contributing to improvement in the overbite during AOB treatment.

The sample used in this study was small, there was no control group and treatment time was too short to make a categorical statement of the behavior of the mandible during AOB treatment with JFO. However, in the sample used in this investigation the mandibular rotation did not appear to be a major factor that influenced the improvement in overbite with JFO during AOB treatment. One interesting point should be discussed.

All patients had a positive Factor 8 (Point G in front of point C) meaning that there had previously been a compensation in the degree of closure of the mandible, according to Simões [3]. It would be very interesting to conduct the same investigation with AOB in individuals with a negative factor 8 (point G behind point G), or even zero (point G in the same horizontal direction of point C) to verify the behavior of mandibular rotation during AOB treatment with JFO.

There are additional resources about functional orthodontics treatment you can find on our website.

Authors: Everaldo Teixeira Costa, Ieda Piramo Moreira Santiago, Orlando Santiago Júnior

References

C. Rijpstra and J. A. Lisson, “Etiology of anterior open bite: a review,” Journal of Orofacial

Orthopedics / Fortschritte der Kieferorthopädie, Vol. 77, No. 4, pp. 281–286, Jul. 2016.

L. S. Todoki et al., “The national dental practice-based research network adult anterior open bite study: treatment success,” American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Vol. 158, No. 6, pp. e137–e150, Dec. 2020.

R. B. Moraes, J. K. Knorst, A. B. R. Pfeifer, F. Vargas‐Ferreira, and T. M. Ardenghi, “Pathways to anterior open bite after changing of pacifier sucking habit in preschool children: A cohort study,” International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 278–284, Mar. 2021.

W. A. Simões, Ortopedia Funzionale dei Mascellari. (in Italian), Orbetello, 2010.

W. A. Simões, “Articular compass: the location of frontal accessories of bioelastic appliances,” Cranio, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 109–125, 1999.

S. Sambataro et al., “Cephalometric changes in growing patients with increased vertical dimension treated with cervical headgear,” Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics / Fortschritte der Kieferorthopädie, Vol. 78, No. 4, pp. 312–320, Jul. 2017.

V. Paoloni, D. Fusaroli, L. Marino, M. Mucedero, and P. Cozza, “Palatal vault morphometric analysis of the effects of two early orthodontic treatments in anterior open bite growing subjects: a controlled clinical study,” BMC Oral Health, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 1–9, Dec. 2021.

S. Moshiri, E. A. Araújo, J. F. Mccray, G. Thiesen, and K. B. Kim, “Cephalometric evaluation of adult anterior open bite non-extraction treatment with Invisalign,” Dental Press Journal of Orthodontics, Vol. 22, No. 5, pp. 30–38, Oct. 2017.

R. Khosravi et al., “Management of overbite with the Invisalign appliance,” American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Vol. 151, No. 4, pp. 691–699.e2, Apr. 2017.

K. Harris et al., “Evaluation of open bite closure using clear aligners: a retrospective study,” Progress in Orthodontics, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 1–9, Dec. 2020.

G. Janson, M. Rizzo, V. Laranjeira, D. G. Garib, and F. P. Valarelli, “Posterior teeth angulation in non-extraction and extraction treatment of anterior open-bite patients,” Progress in Orthodontics, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 1–7, Dec. 2017.

A. Vela-Hernández, R. López-García, V. García-Sanz, V. Paredes-Gallardo, and F. Lasagabaster-Latorre, “Nonsurgical treatment of skeletal anterior open bite in adult patients: Posterior build-ups,” The Angle Orthodontist, Vol. 87, No. 1, pp. 33–40, Jan. 2017.

A. Aliaga-Del Castillo, L. Vilanova, F. Miranda, L. E. Arriola-Guillén, D. Garib, and G. Janson, “Dentoskeletal changes in open bite treatment using spurs and posterior build-ups: A randomized clinical trial,” American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Vol. 159, No. 1, pp. 10–20, Jan. 2021.

M. Wang, B. Zhang, L. Li, M. Zhai, Z. Wang, and F. Wei, “Vertical stability of different orthognathic treatments for correcting skeletal anterior open bite: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” European Journal of Orthodontics, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2022.

W. Du, G. Chen, D. Bai, C. Xue, W. Fei, and E. Luo, “Treatment of skeletal open bite using a navigation system: CAD/CAM osteotomy and drilling guides combined with pre-bent titanium plates,” International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Vol. 48, No. 4, pp. 502–510, Apr. 2019.

M. T. C. Soares and O. Santiago Jr., “Is jaw functional orthopedics an efficient tool to treat anterior open bite? A retrospective study,” Jaw Functional Orthopedics and Craniofacial Growth, Jun. 2022.

O. Santiago Jr and I. P. M. Santiago, Atlas de Construção de Aparelhos Ortopédicos Funcionais. (in Portuguese), Orlando, 2010.