Fractures of the lower jaw in children

Machine translation

Original article is written in RU language (link to read it) .

A mandibular fracture can cause severe pain for a child and extreme anxiety for a parent or caregiver. Although the pattern of fractures and related injuries is similar in children and adults, the incidence is quite low. Due to a number of factors, including the anatomical complexity of the developing mandible in a child, the treatment of these fractures differs from that in adults and can pose great challenges to the pediatric dentist.

Learn more about jaw fractures in children at the webinar Fractures of teeth and jaws in children and adults .

Various treatment options for mandibular fracture are available, such as closed/open mouthguard with fixation around the mandible, archwire fixation, and cemented mouthguard. This article examines 19 cases of fracture using various treatment methods.

Fractures of the lower jaw are among the most common in young patients. The incidence of mandibular fractures in children ranges from 0.6% to 1.2%. The most common causes of fracture in children were falls (64%), motor vehicle accidents (22%), and sports-related accidents (9%). Fractures of the mandible usually cause dental injuries (39.3%). Additionally, it is widely believed that fracture patterns change with age. McGraw and Cole reported that fractures move from the upper to the lower region of the face with increasing age.

Fractures of the mandible can be diagnosed clinically but must be confirmed radiographically. Fractures occurring in children present challenges in achieving and maintaining stability. Treatment of children is difficult due to the anatomical complexity of the developing lower jaw, the presence of tooth germs and the eruption of temporary and permanent teeth. The most common treatment methods are cap splints with fixation around the lower jaw, cementation of the tray on the dental arch and fixation of the dental arch according to Erich.

This article presents various treatment methods for mandibular fractures in children.

Clinical cases: patient selection

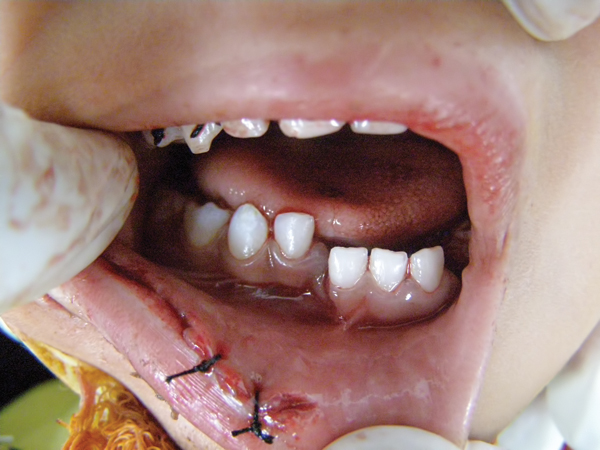

Nineteen patients aged 3 to 12 years with maxillofacial lesions (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2) were reviewed by the Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry at KD Dental College and Hospital, Mathura, India.

Fig.1

Fig.2

Fig.2

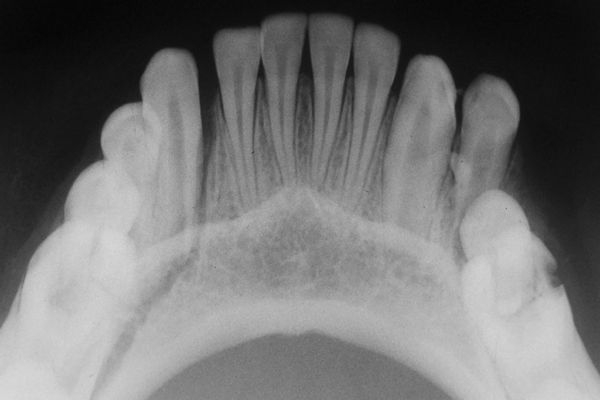

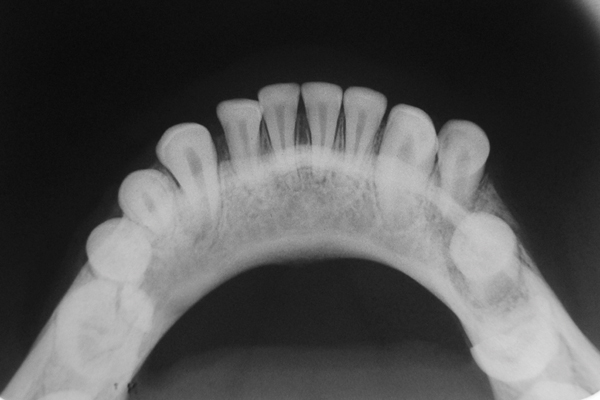

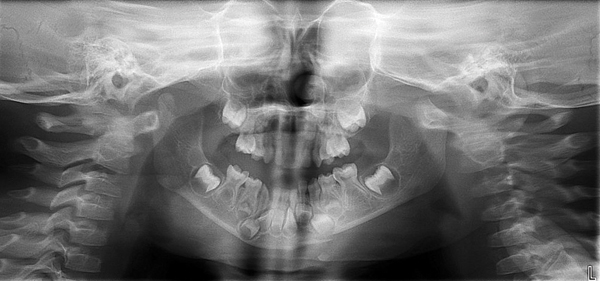

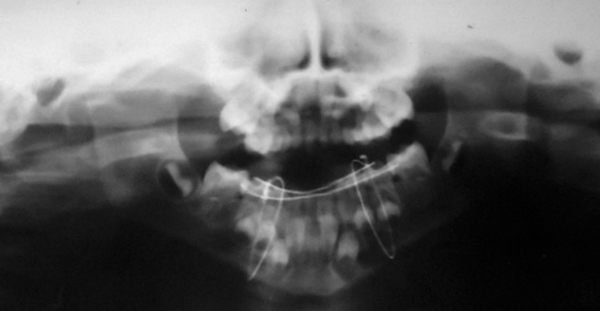

Detailed case histories were collected, and clinical and radiographic examinations such as orthopantomography, occlusal radiography, and intraoral periapical radiography were performed (Figure 3 to Figure 8). After a thorough assessment, a diagnosis of the type of fracture was made and a treatment plan was created for each patient. Informed consent was obtained from the parent, and in some cases the treatment was performed under general anesthesia with written consent obtained from the parent.

Fig.3

Fig.4

Fig.5

Fig.6

Fig.7

Fig.8

Preparation of acrylic splints

For each patient, alginate impressions were made on the upper and lower jaws and models were prepared. In cases of displaced fracture, surgery was performed on cast models (Fig. 9 and Fig. 10). After preparation on the models, they were installed in a modified position, and correct occlusion was obtained with the opposite upper jaw. Both models were stabilized and installed in the articulator. The splint was fabricated using self-curing acrylic resin incorporating labial and buccal projections (Figure 11).

Fig.9

Fig.10

Fig.11

For displaced fractures

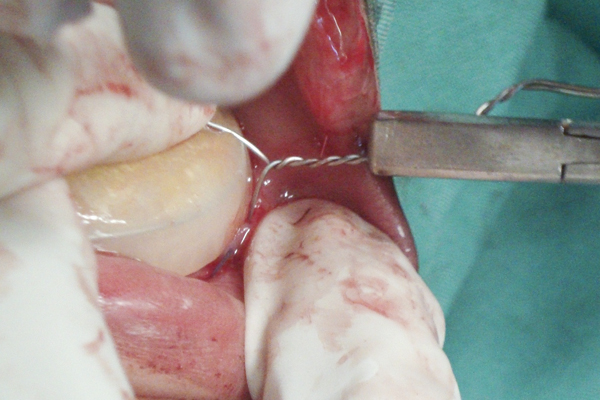

In children with displaced fractures, the dental arch of the lower jaw was manually reduced under general anesthesia with occlusion in the recommended position, and an acrylic splint was installed. Piercing incisions were placed in the submandibular and submental areas to facilitate passage of the Kelsey-Fry mandibular bone awl, which was passed lingually along the body of the mandible through the incision and piercing the lingual mucosa. A 26-gauge orthodontic wire was applied to the awl. Once the wire was attached to the awl, it was not removed until the tip of the awl reached the inferior border of the mandible, and then the wire was carefully moved into the buccal groove along the body of the mandible to prevent injury. A wire was passed on each side, taking precautions to avoid injury to the neurovascular bundle at the mental foramen. (Fig. 12).

Fig.12

For non-displaced fractures

In children with non-displaced fractures, a prepared acrylic splint was placed on the mandibular arch and occlusion was checked. Once proper occlusion was achieved, the splint was cemented directly to the dental arch using glass ionomer cement. (Ketac™ Cem, 3M ESPE, www.3MESPE.com) (Figure 13).

Fig.13

Fixing the arc

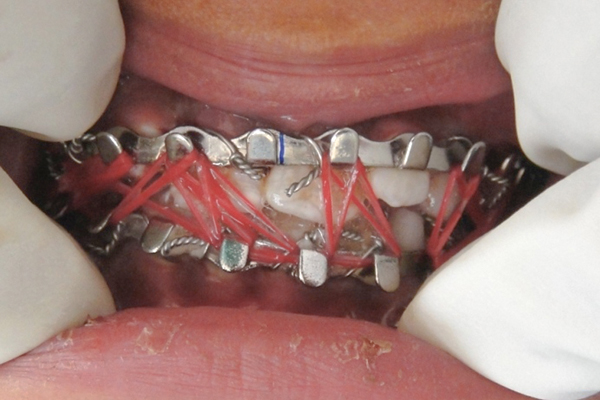

Before placing the archwire, the occlusion was checked to confirm that the teeth were fully displaced in their normal contact. The factory archwire was carefully adjusted in shape and length to avoid damage to the gum tissue. The archwire was adapted close to the dental arch and placed between the equator of the tooth and the gum. The arch was extended to the last tooth on both sides of the mouth. The brackets were placed symmetrically on the upper and lower jaws to achieve the design (reliable) tension forces on both arches for functional training using elastic materials. To secure the archwire, a ligature was prepared on each side in the premolar area. The dental arch was positioned and secured using a wire twister. The wire was cut with a router and the ends were turned away from the gum to prevent damage. Fixation of the maxillofacial area was performed using elastics (elastic rods) for intraoperative control of occlusion (Fig. 14).

Fig.14

Each patient was given postoperative instructions, a soft and liquid diet was recommended, and antibiotic prophylaxis was prescribed.

results

In all patients, splints and arches were removed after 2-4 weeks. Postoperative radiographs were obtained to confirm healing of the fracture site before splint removal (Figure 5 and Figure 8), and all patients were followed for 12 months. None of the patients had complications in the postoperative period; unprecedented healing and union of the fracture segments occurred in all patients. In one patient, healing time was prolonged due to dislodgement of the splint, which was re-cemented. There was a slight discrepancy in occlusion in a few patients, which self-corrected over time.

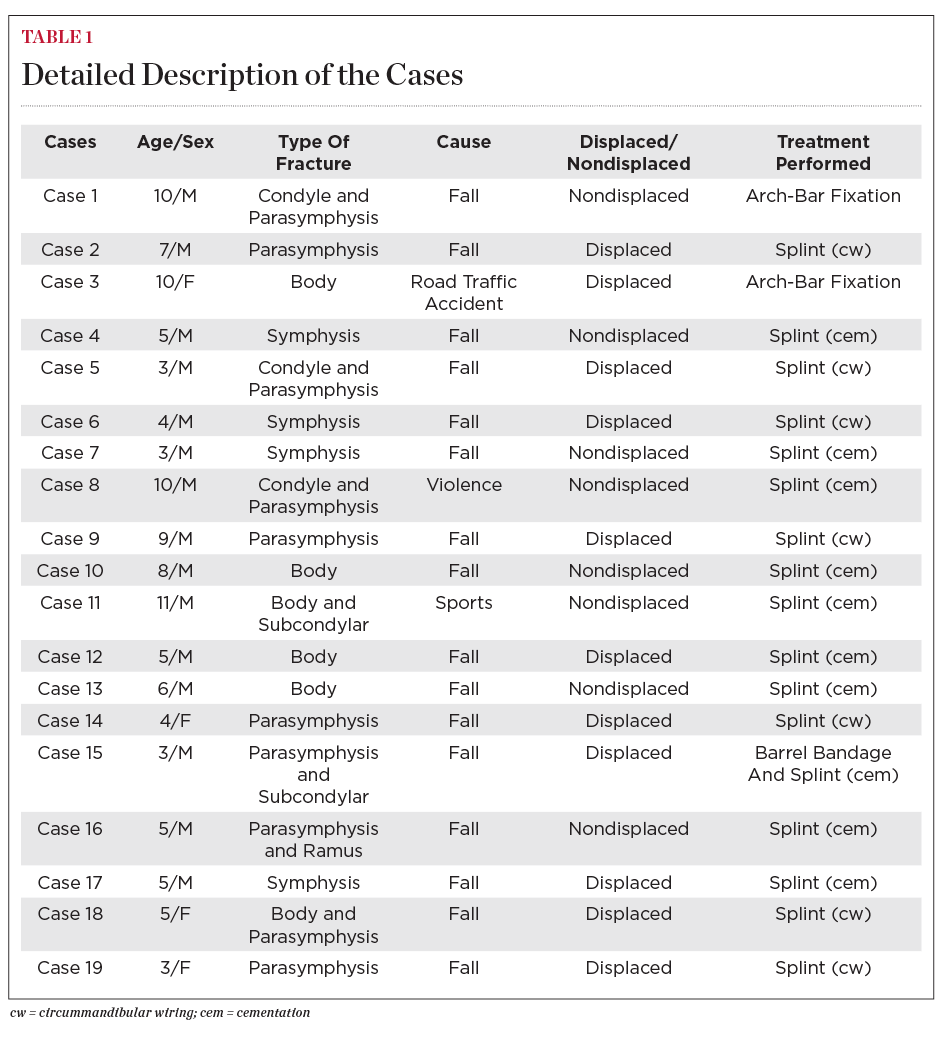

Maxillofacial injuries in children

Maxillofacial injuries in children are uncommon. Can be observed in various areas of the mandible, including the condyle, alveolus, body, symphysis, parasymphysis, angle, ramus and coronoid process, according to Haug and Foss. Of the 19 cases presented in this article, eight were fractures in the symphysis/parasymphysis, four in the body of the mandible, four in the parasymphysis, and there were isolated cases of fracture of the body and condyle, body and parasymphysis, ramus and symphysis (Table 1 ). In this case series, the most common etiology was falls, accounting for 80% of all children. Most children were under 6 years of age (12 children), with a male to female ratio of 4:1.

Treatment of mandibular fractures in children differs somewhat from that in adults, including anatomical changes, rate of healing, degree of patient cooperation, and potential for changes in mandibular development. The method of treating fractures in the lower jaw in children depends on the age and stage of dental development. Minimally displaced fractures can be treated with a soft diet, pain medications, and antibiotics. However, in very young children, healing may be prolonged due to lack of cooperation. In such cases, fabricating a splint and cementing it onto the dental arch can be used to overcome these obstacles.

In the present case series, six patients reported an irregular symphysis/parasymphysis fracture that was treated with acrylic splints secured to the dental arch for an average of 2 weeks. All 19 patients showed satisfactory healing within 2-3 weeks without complications. In addition, reduction of the oral gap was a common feature in children after mandibular fracture, which improved over time (Fig. 15 and Fig. 16). Displaced fractures should be reduced and immobilized. Children demonstrate greater osteogenic potential and higher rates of healing than adults. Therefore, anatomical displacement in children should be performed earlier and the immobilization time should be shorter (2 weeks).

Fig.15

Fig.16

In the present case series, seven displaced fractures were reduced and immobilized using splints with wires around the mandible, two cases were treated with wire fixation, and one case had a splint attached to the dental arch. A case where the splint was cemented showed delayed healing due to splint displacement that occurred due to dissolution of the cement. Previous studies have shown that the use of archwire restricts normal food intake in children, resulting in significant weight loss. Here, in the present case series, maxillofacial fixation was performed using elastics so that an active exercise program could be initiated as soon as the child was able to cooperate. Prolonged periods of maxillofacial fixation can lead to ankylosis in children and should be avoided. In cases of muscle fractures, non-operative rehabilitation is very popular because there are minimal complications and the results are good in both adults and children. In addition, in older children, the bone has less ability to adapt and remodel, and the height of the ramus cannot be restored.

In this case series, the condylar fracture was associated with the symphysis/parasymphysis, ramus, or body of the mandible. In such cases, emergency use of a cylindrical cast along with a soft and liquid diet was recommended until the jaw was immobilized with a splint. The muscles showed remodeling over time. Open displacement with rigid internal fixation is rarely used for condylar fractures unless the displaced fragment creates a mechanical obstruction. Condylar fractures are more common in children than in adults (50% of mandibular fractures versus 30%) because the child's highly vascularized condyle and thin neck are poorly resistant to the impact forces generated by falls. In children younger than 6 years of age, condyle fractures are more often intracapsular than extracapsular. In children over 6 years of age, most condyle fractures usually occur due to trauma to the neck. Although a conservative approach is preferred in children, open reduction is sometimes required and internal fixation is necessary in cases of bone fractures associated with symphysis/parasymphysis fractures to ensure stabilization of the symphysis/parasymphysis region and to facilitate healing. Pain detected immediately after injury in children with a condylar fracture is caused by muscle spasm, which resolves after 3-4 days without the use of maxillofacial fixation.

Correction of mandibular fractures

Repairing mandibular fractures in children is a challenge given the child's age and anatomical changes. In this article, the most common fracture was the symphysis/parasymphysis (42%). The role of the pediatric dentist is vital in the rehabilitation of children with such fractures. If proper principles are followed, satisfactory results can be achieved in children with minimal discomfort.

Even more useful information about childhood trauma in the online course “Acute” issues in pediatric dentistry .