Do External Factors Afect Materials’ Evaluation and Preferences? Comments Related to Observations from a Focus Group

Abstract

Purpose of Review To discuss if external factors can afect materials’ evaluation and preferences. Restorations were placed by a group of dentists in standardized cavities in typodont teeth under two conditions: the double-blind test, with unidentifed composites, and the conscious test, with materials available in the original packages. Viscosity, adherence to the instrument, ease of sculpture, and general handling were evaluated. There are additional details about composite restoration protocols that you can obtain on our website in Direct Restoration section.

Recent Findings Ease of use and literature were the most considered criteria, while material’s cost and peer opinion were the ones with the greatest disagreement. Both the degree of satisfaction and the selection of the preferred material were dependent on the condition of the evaluation.

Summary External factors afect materials’ evaluation and preferences.

Introduction

The common approach to the evaluation of dental materials is to begin with in vitro experiments studying the material’s physical, mechanical, and biological properties, as well as other important aspects such as overall stability, surface topography/polishability, color and aesthetics, and handling characteristics [1, 2]. In the ideal situation, such evaluations would be followed with clinical trials, where materials are assessed over many years because of pre-established criteria, providing the practitioner with objective guidance for material selection [3]. Due to the rapid introduction and wide-spread distribution of dozens of diferent brands and types of the same material, such complete documentation is rarely available, forcing the clinician to select specifc materials based on more subjective information. While this process is of fundamental importance to a dental practice, surprisingly little has been published about the most important factors that infuence material selection by dental clinicians [4].

The selection of resin composites for dental restorative work provides an appropriate case for studying this selection process, since they are routinely used in clinical practice and are sold by a wide variety of manufacturers. Based on composition, most specifcally the formulation and proportion of the organic and inorganic phases, the material will present aesthetic and functional characteristics that could make it suitable for restoring anterior and/or posterior teeth [4, 5]. In the end, the quality of the restorative procedure will depend on the correct indication and application of the chosen material [5, 6]. Thus, it is useful to determine, just what are the factors that really infuence the choice of a given dental composite material by a clinician?

It would be expected that the choice of a resin composite is related to personal experience, brand/trademark, recommendation of experts, price, handling characteristics, and other factors that must be considered and thus are not mutually exclusive. For example, handling characteristics is a subject of interest to researchers and clinicians and its evaluation can be conducted through objective laboratory studies of rheological properties, adherence to the cavity or instruments, and maintenance of shape [7, 8]. But subjective clinical assessments made during the flling of a cavity preparation may provide more important information about this characteristic to the operator and conceivably may also be infuenced by external factors such as the “fame” (“popularity”) and cost of the given material [9–12]. To address this complex topic of dental material selection, it is important to discuss if external factors can afect materials’ evaluation and preferences.

Focus Group—Dynamics and Outcomes

A group of 15 dentists from the post-graduation program of Veiga de Almeida University (Research Ethics Committee; CEP/UVA 1,436,336) was invited to participate as a focus group.

Stage 1: Compliance with Pre‑established Criteria for the Selection of Resin Composites

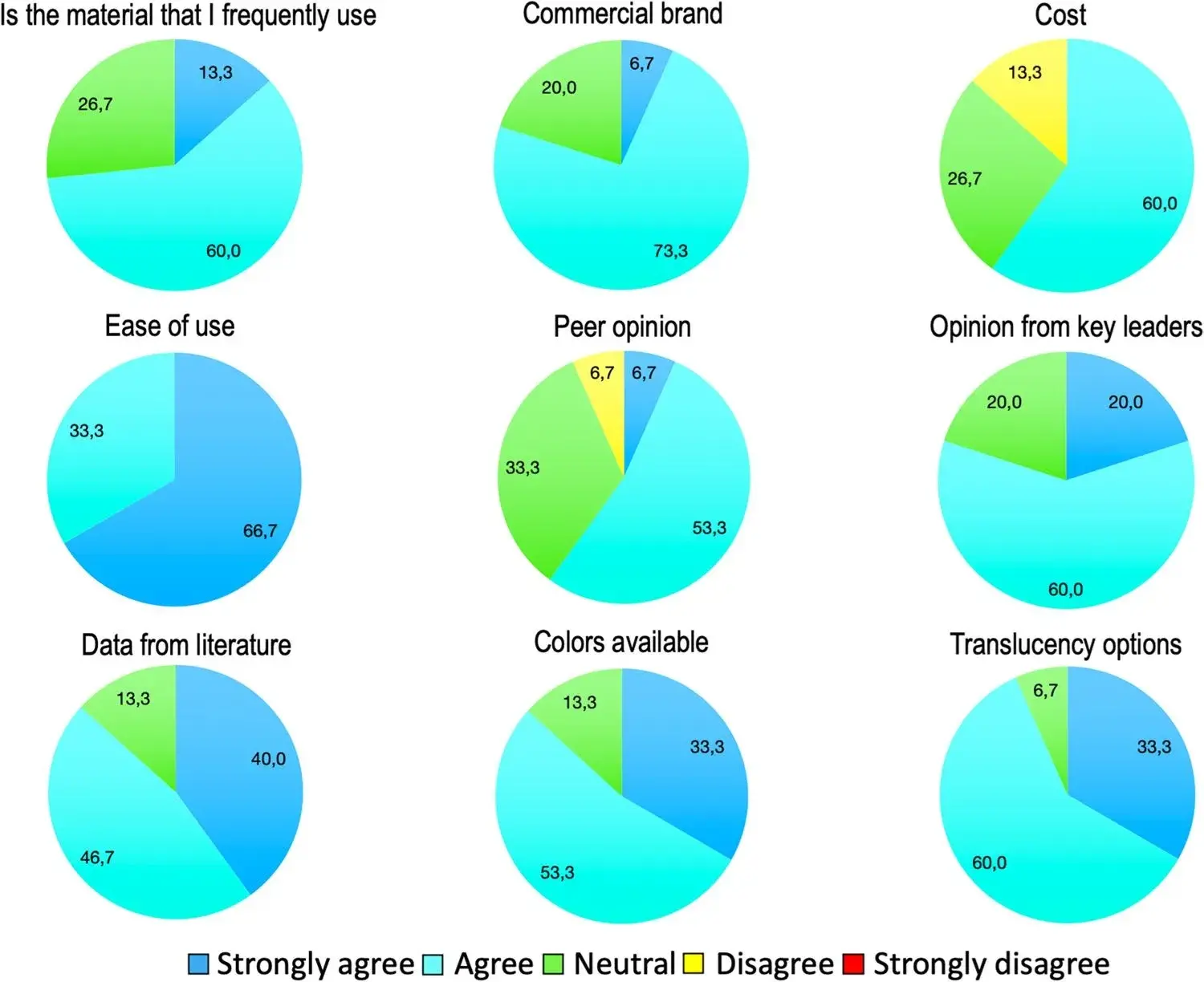

The first part of the dynamics consisted of the participants individually flling out a form to provide their opinion about the importance of certain criteria in composite selection. Figure 1 details the focus group member’s agreement with pre-established criteria in the selection of resin composites. The percent of the participants who answered strongly agree or agree ranged from 60 to 100% for the nine criteria, with the highest level of “strong agreement” for the topic “ease of use.” Therefore, the agreement between the participants was very high. There was only some level of disagreement with the criteria “peer opinion” and “cost,” but this only reached 6.7% and 13.3%, respectively. The greatest level of neutrality was found with peer opinion (33.3%).

Stage 2: Materials’ Handling Characteristics and Selection

The second part consisted of the manipulation and selection of materials both blindly and consciously. In this stage, each participant received 6 standardized and coded syringes of dental composite, 6 typodont teeth each containing one class II standardized cavity, a spatula of standardized size, a light-curing unit, other disposables, and individual protection equipment. For the evaluation of each material’s handling characteristics, all clinicians were asked to quickly handle all the materials but without giving any opinions or recording any information. This was important for everyone to have a frst impression of the materials in a general sense. Next, the participants restored each tooth with a diferent composite and immediately recorded his/her opinion about their perception of the materials. After working with all the materials, the participant was asked to choose the preferred material in an electronic form.

Fig. 1 The importance of pre-established criteria in the selection of resin composites according the current focus group

Fig. 1 The importance of pre-established criteria in the selection of resin composites according the current focus group

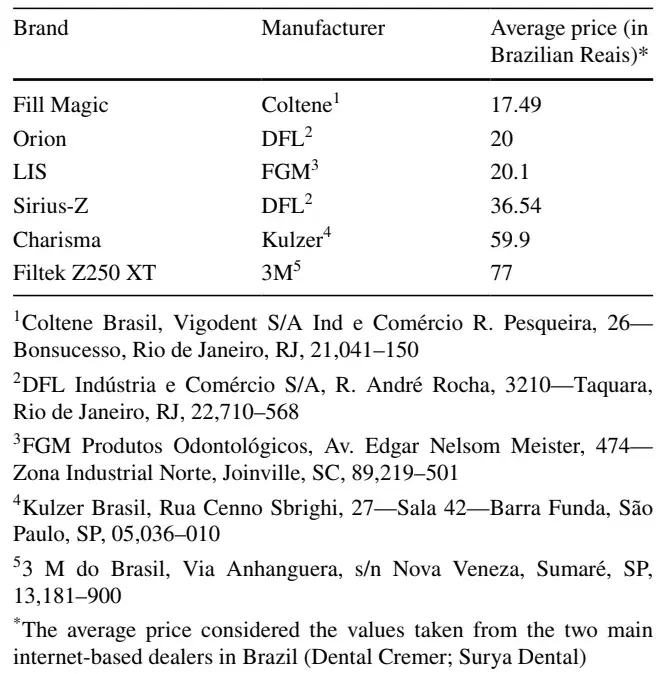

The second handling test was conducted in a similar way that was carried out in the blinded test, but with the main diference being that the participants received the composites in their original packaging. Information of each tested material as well as the average cost per syringe was supplied (Table 1). Thus, the clinicians had the chance to handle the resin composites, now identifed as Fill Magic (Coltene), Orion (DFL), LIS (FGM), Sirius-Z (DFL), Charisma (Kulzer), and Z250 (3 M), all A2 shade. These materials were selected because they are in the price range of up to 89.00 Brazilian Reais (R$, 20.00 US Dollars at the time) at the time of the study. After evaluating each material according to the same criteria used in the blinded test, the participant was asked to select the material of his/her preference.

Figure 2a to f show the agreement levels for the afrmative statements regarding handling characteristics, both in the blinded and in the conscious tests. It is possible to verify the increase in the disagreement level for the four statements made for the three lowest cost materials (Fill Magic, Orion, and LIS).

Sirius-Z resin, which most closely refects the intermediate price of the tested materials, presented a low variation between the results obtained in the two scenarios, with a small increase in the level of disagreement with the viscosity evaluation. Charisma and Filtek Z250 XT showed a positive variation for all the four statements, suggesting that the participants had a more favorable opinion of these materials’ handling characteristics once they were identifed to them.

Considering the overall preferences, Charisma and Sirius-Z were the preferred resin composites (33% each) for most participants in the blind test while Filtek Z250 XT was selected by the majority in the conscious test (67%).

Table 1 Basic information provided for the participants

Fig. 2 Agreement level obtained by Likert’s scale for each afrmative, both in the blinded test and in the conscious test, for the resin composite. a Fill Magic, b Orion, c LIS, d Sirius-Z, e Charisma, and f Filtek Z250 XT

Fig. 2 Agreement level obtained by Likert’s scale for each afrmative, both in the blinded test and in the conscious test, for the resin composite. a Fill Magic, b Orion, c LIS, d Sirius-Z, e Charisma, and f Filtek Z250 XT

Stage 3: Discussion with Clinicians

After the evaluation sessions, a group discussion was held with the clinicians. Three specifc topics were discussed with the group: (1) whether this experience could change their clinical routine in relation to the materials they choose or their selection process; (2) if reviewing a scientifc article published in a high-quality journal could change their opinion about a less popular or newly released material; and (3) factors that could lead to choosing a material with reduced cost. The audio of the conversation was recorded, with everyone’s knowledge and consent for further analysis by the study team.

Most of the participating dentists would not change their daily choice of composite and would keep the same materials with which they were used to working. When questioned if reviewing a scientifc article published in a high-quality journal could change their opinion about a less popular or newly released material, the group was unanimous in their opinion that scientifc works are usually very limited and that they would prefer to receive information from more experienced colleagues. Furthermore, the participants confrmed that familiarity with a material/brand is crucial, but that they would work with cheaper materials to meet specifc demands, if it is within minimum quality standards.

Comments Related to the Outcomes

The first phase of the dynamic was designed to verify the extent to which clinicians agreed with nine pre-established criteria relating to their choice of resin composites. The highest agreement was obtained for the “ease of use” criterion, and this is probably associated to the fact that the clinicians were instructed to perform an evaluation on the handling characteristics of these resin composites. On the other hand, the highest indices of disagreement or neutrality were related to the “cost” and “peer opinion” criteria. This may be associated with the desire of the clinicians to demonstrate implicit independence regarding their choice or deemphasize the “non-scientifc” aspects in their material selection process. Researchers in the feld of social psychology report that using questionnaires to verify what a person thinks about something is inefcient because it is a portrait of the so-called explicit attitude [13]. This refects an opinion or belief that a person states “out loud” or in response to being “questioned” by someone. It involves a high degree of confrmation bias, where common sense has a tendency to search the memory for only evidence that confrms or supports an idea. This is why complementary tests are necessary to verify the “implicit attitude”—which better refects what someone really thinks [13]. Thus, this test format is not a question related to character, omission, or any other negative aspect, but more likely refects the fact that most human beings tend to want to act as a part of a group.

As it was seen, there was a change in the amount of agreement according to the degree of awareness about the materials being evaluated. A depreciation of the less expensive materials and a higher valuation of those at the more expensive end of the range were evident. Similarly, there was a large discrepancy related to the material that the clinicians selected at the end of the two studies, again with a concentration on the same material.

Considering the results of the choices that the participants made at the end of each practice session draws attention to the great diference that occurred for the resin composite Filtek Z250 XT. For the blinded test, this material was only preferred by about 13% of the participants; in contrast, it was preferred by nearly 67% of the participants in the conscious test.

Thus, it is possible that the dentist’s level of consciousness of a specifc material has a greater impact on their fnal choice than the resin composite price [9].

The cost of a given material can depend on many things, including very precise parameters such as the cost of the raw materials, the manufacturing process (with the variable and permanent associated costs), the extent of research and development, and the quality of the packaging processes [14]. However, other factors need also to be considered, such as marketing, advertising, and, fundamentally, the maximum amount that a person or a certain group is willing to pay to have a certain product or service. Cost-efectiveness has been a topic addressed in recent studies in dentistry [15–17, 18•], but there is no information assessing whether the price of a resin composite can be directly associated with the quality or longevity of the restoration.

The explanation for this change in behavior in relation to the perception of materials in both scenarios is not simple and is probably associated with several factors. The frst, and perhaps most emblematic, is “social pressure”—which is defned as the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of individuals being infuenced by the real, imagined, or implied presence of others [12, 13, 19]. Several social psychology studies have pointed out that the opinion of social groups can have the efect of “pressure” and suppression of individual thinking, leading to the conformity of ideas. Thus, an evaluator can alter both the perception and the fnal choice because he or she does not want to deviate from what is considered the norm, imposed by various means, as seen below, even if unconsciously. In a large part, this could also be considered a self-validation process [12, 13, 19].

Aspects related to the advertising, popularity, or renown of a particular material or manufacturer might infuence participants’ opinions. For example, a multinational company, with a long tradition in the area of dental materials, manufactures the material in this study that showed the most positive variation from the blinded to the conscious study. In addition, as noted in the frst phase of the study, most clinicians already used the materials from this company, which likely impacted their choice once they knew what the material was. Studies indicate that it is very difcult to verify what are the aspects related to clinical behavior that causes a clinician to make a certain choice of material, but that habit exerts a great infuence [11].

Faced with the complexity involved with human behavior, studies carried out in the format of focus groups are crucial [11, 20•]. Focus groups are qualitative analyses that involve exploratory tools and may involve other methods, as in the case of this study, which used a practical evaluation. Analyses using the format of focus groups began in the feld of social sciences but have become widely used in marketing, as it is extremely useful to understand how people consider an experience, an idea, or an event. Some basic aspects need to be considered when employing focus groups, such as the sample size, which needs to be relatively small so that all participants can adequately interact and have their opinions noted. It is also essential that there are predetermined topics to be addressed by the study coordinators during the discussion with the entire group so that there is no loss of focus [21, 22].

By asking whether this experience could change their clinical routine in relation to the materials they choose or their selection process, it was determined that the vast majority would not change their daily choice of composite. However, it is important to emphasize the extent of the surprise displayed by the participants when the results were revealed to them. This suggests that dentists often make choices of material or technique that appear to run counter to their own common sense.

The second topic addressed if scientific data could change their opinion about a less popular or recently launched material. The participants agreed that scientifc data is important, but at the same time, the data usually presented by academic sources are limited and that in the end they tend to consider the opinion of more experienced colleagues as being more infuential and clinically relevant, a behavior commonly described in the literature related to the adoption of new technologies [11, 23••]. Interestingly, this outcome contradicts the results gathered in stage 1—where the agreement with item “data from literature” is much higher than with “peer review”—and reinforces how far the implicit attitude can completely difer from the explicit one, as already discussed with the fndings from stage 1.

Finally, the group discussed choosing a material being sold at reduced cost, and there was consensus that the social class of the patients in the practice could impact this decision, but only provided that the material maintained a minimum standard of quality. At this point, one participant reported being concerned that less expensive products were rarely based on scientifc literature and therefore wondered what information sources could be consulted to verify that a minimum quality standard was being met. The group ultimately agreed that the search for information was fundamental but that the fnal result of the work depended on the operator.

It is important to fundamentally note that the level of discussion with the present focus group was extremely high and consistent with the clinicians who were taking a strict sensosuperior course, in which critical thinking is stimulated.

If you enjoyed reading the article and would like to explore the direct restoration topic further, we encourage you to enroll our course "Brazilian School of Aesthetic Restorations".

Conclusion

Both the degree of satisfaction and the selection of the preferred material were dependent on the condition of the evaluation. Implicit attitudes may difer from explicit ones as external factors afect materials’ evaluation and preferences.

Declarations

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical Standard. Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Conflict of Interest Luis Felipe Schneider declares that he has received a consultant honorarium from DFL Company. Andrea Soares Quirino declares that she has no confict of interest. Larissa Maria Cavalcante declares that she has no confict of interest. Jack Ferracane declares that he has no confict of interest.

List of authors:

Luis Felipe J. Schneider, Andrea Soares Quirino, Larissa Maria Cavalcante, Jack L. Ferracane

References

Ilie N, Hilton TJ, Heintze SD, Hickel R, Watts DC, Silikas N, Stansbury JW, Cadenaro M, Ferracane JL. Academy of Dental Materials guidance-resin composites: part I-mechanical properties. Dent Mater. 2017;33:880–94. .

Ferracane JL, Hilton TJ, Stansbury JW, Watts DC, Silikas N, Ilie N, Heintze S, Cadenaro M, Hickel R. Academy of Dental Materials guidance-resin composites: part II-technique sensitivity (handling, polymerization, dimensional changes). Dent Mater. 2017;33:1171–91.

Opdam N, Frankenberger R, Magne P. From ‘direct versus indirect’ toward an integrated restorative concept in the posterior dentition. Oper Dent. 2016;41:S27–34.

Alexander G, Hopcraft MS, Tyas MJ, Wong R. Dentists’ restorative decision-making and implications for an ‘amalgamless’ profession. Part 4: clinical factor. Aust Dent J. 2017;62:363–71.

Bayne SC, Ferracane JL, Marshall GW, Marshall SJ, van Noort R. The evolution of dental materials over the past century: silver and gold to tooth color and beyond. J Dent Res. 2019;98:257–65.

Ferracane JL, Lawson NC. Probing the hierarchy of evidence to identify the best strategy for placing class II dental composite restorations using current materials. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2021;33(1):39–50.

Kaleem M, Satterthwaiti JD, Watts DC. A method for assessing force/work parameters for stickiness of unset resin-composites. Dent Mater. 2011;27:805–10.

Ertl K, Graf A, Watts D, Schedle A. Stickiness of dental resin composite materials to steel, dentin and bonded dentin. Dent Mater. 2010;26:59–66.

Donovan TE. Promising indeed: the role of ‘“experts”’ and practitioners in the introduction and use of new materials and techniques in restorative dentistry. J Esthet Rest Dent. 2004;16:331–4.

Bonetti D, Johnston M, Clarkson JE, Grimshaw J, Pitts NB, Eccles M, Steen N, Thomas R, Maclennan G, Glidewell L, Walker A. Applying psychological theories to evidence-based clinical practice: identifying factors predictive of placing preventive fssure sealants. Implement Sci. 2010;8:25.

Matthews DC, McNeil K, Brillant M, Tax C, Maillet P, McCulloch CA, Glogauer M. Factors infuencing adoption of new technologies into dental practice: a qualitative study. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2016;1:77–85.

Mallinson DJ, Hatemi PK. The efects of information and social conformity on opinion change. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0196600.

Richardson DC. Social psychology for dummies. Hoboken: Wiley; 2014.

Shaw K, Martins R, Hadis MA, Burke T, Palin W. ‘Own-label’ versus branded commercial dental resin composite materials: mechanical and physical property comparisons. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2016;24:122–9.

Schwendicke F, Stolpe M. Restoring root-canal treated molars: cost-efectiveness-analysis of direct versus indirect restorations. J Dent. 2018;18:37–42.

Schwendicke F, Göstemeyer G, Stolpe M, Krois J. Amalgam alternatives: cost-efectiveness and value of information analysis. J Dent Res. 2018;97:1317–23.

Schwendicke F, Kramer EJ, Krois J, Meyer-Lueckel H, Wierichs RJ. Long-term costs of post-restorations: 7-year practice-based results from Germany. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(4):2175–81.

Braga MM, Machado GM, Rocha ES, ViganÓ ME, Pontes LRA, Raggio DP. How can we associate an economic evaluation with a clinical trial? Braz Oral Res. 2020;34 Suppl 2:e076. This review presents fundamental basic elements to be considered in studies related to the infuence of economic aspects on clinical aspects.

Asch SE. Opinions and social pressure. Sci Am. 1955;193:31–5.

Thyvalikakath T, Song M, Schleyer T. Perceptions and attitudes toward performing risk assessment for periodontal disease: a focus group exploration. BMC Oral Health. 2018; 18(1):90. It presents an interesting example of the application of the use of focus groups.

Kredo T, Cooper S, Abrams A, Muller J, Volmink J, Atkins S. Using the behavior change wheel to identify barriers to and potential solutions for primary care clinical guideline use in four provinces in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):965.

Davis AL, Zare H, McCleary R, Kanwar O, Tolbert E, Gaskin DJ. Maryland dentists’ perceptions and attitudes toward dental therapy. J Public Health Dent. 2020;80(3):227–35.

Heft MW, Fox CH, Duncan RP. Assessing the translation of research and innovation into dental practice. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2020;5:262–270.

/public-service/media/default/184/77OOf_65312297d7ef3.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/186/1Vv5n_653122c853165.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/478/KvUj4_671f55677a456.png)