Alternative treatment to orthognatic surgery by the application of digital smile planning

Abstract

Through the use of the application of a mathematical proportion and a digital golden ratio compass associated with computer software, Digital Smile Planning (DSP) can assist clinicians to achieve the fundamentals of esthetic treatment. The present clinical report describes the application of this technique to propose an alternative and more conservative treatment for a patient who refused the option of orthognathic surgery. Additional information about digital technology in dentistry are accessible for you to learn on our website in Digital Dentistry section.

To address the diagnosis of a gingival smile with vertical maxillary excess, the alternative treatment comprised crown lengthening surgery, ceramic veneers on the maxillary teeth, and the application of botulinum toxin to reduce lip hyperactivity. Considering the successful resolution of the patient’s situation from the perspective of both the dentist and the patient, the application of DSP was considered to be useful to achieve predictable harmony between the face and the dental structures.

Introduction

Oral health perception and its psychosocial impact on modern life have increased the demand for esthetic dental treatments. In recent years, the method by which dentists plan oral rehabilitation has been significantly modified. Digital technologies have transformed patient care by broadening treatment options and operative approaches across all areas of dentistry.[2]

The digital workflow can improve dentists’ ability to develop an effective diagnosis and consistent treatment plan, and, as a result, a comprehensive restorative solution.[3,4]

The advent of tools such as Digital Smile Planning (DSP) allows professionals to plan a patient’s smile using the application of mathematical proportions.[5,6] This method is useful as a starting point in achieving facial harmony and esthetics in the anterior maxilla.[7]

Logically, a reduction in operative time and an improvement in patient psychologic and physical comfort can be achieved due to the predictability offered by the digital workflow.[8]

DSP is a technique that associates golden ratio proportions using commercially available computer presentation software (Keynote; Apple, or PowerPoint; Microsoft) and resources such as a golden ratio digital compass, caliper rule, intraoral and extraoral photographs, and plaster study casts. The compass is used to analyze the positioning of the smile line and incisal edge using as reference the corner of the eye, nose base height, and incisal edge of the central incisor.[9,10] After the planning is completed, the information is transferred from the 2D computer model to a personalized plaster cast as a wax-up. This process facilitates the communication between the dental surgeon, patient, and prosthetics technicians and reduces mistakes, providing predictable outcomes.[11]

Among the causes of esthetic discomfort leading patients to seek dental treatment is excessive gingival display (EGD) or so-called ‘gummy smile.’ This is an individual condition that has a significant impact on quality of life and esthetic self-perception.[12-14] Published studies generally have reported that gingival exposure of > 3 mm is considered unattractive.[15,16] The etiology of this condition varies, with dental, skeletal, and muscular causes that might act in isolation or in combination.[16] An accurate diagnosis of the etiology of this condition is essential in selecting the most appropriate treatment protocol. For more pronounced cases, orthognathic surgery is indicated.

The treatment of malocclusion with skeletal deformity is generally managed with both orthognathic surgery and orthodontic treatment.[17] Orthodontic patients usually pursue the recovery of masticatory function, although some patients seek procedures to improve esthetics and self-esteem rather than occlusion.[18] In such situations, including in the case of EGD, alternative therapies can be proposed that require less invasive treatment. Examples include the application of botulinum toxin (BTX) to the lip elevator muscles, or in the case of Class III patients, compensatory orthodontic movements can be performed. Consistent results are not always obtained with these alternative therapies, as major skeletal movements are only possible through surgery. However, the disadvantages of orthognathic surgery are numerous, including the need for general anesthesia, hospitalization, and a long and painful postoperative period. Thus, this treatment plan may not be well accepted by patients due to the significant surgical involvement required.[18]

Considering the aforementioned points, the purpose of the present clinical report is to present an alternative solution to orthognathic surgery for the treatment of EGD caused by a combined etiology of a vertical maxillary excess (VME), hyperactive upper lip, and altered passive eruption (APE).

Case report

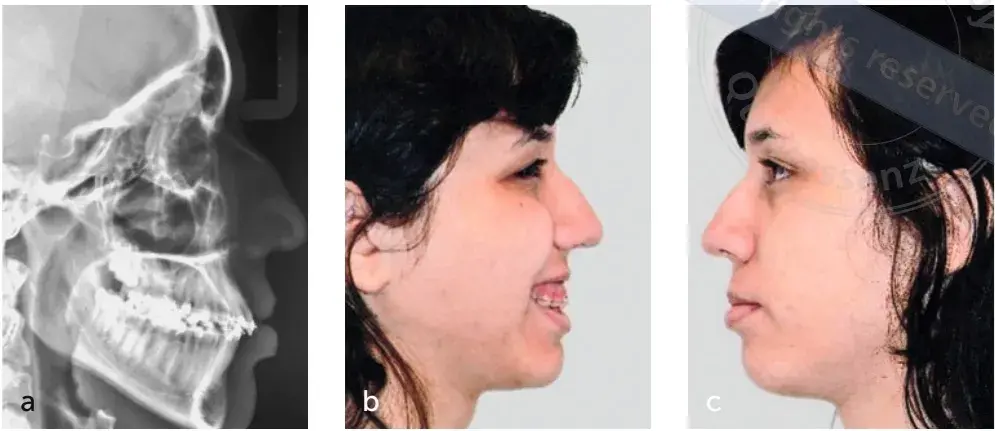

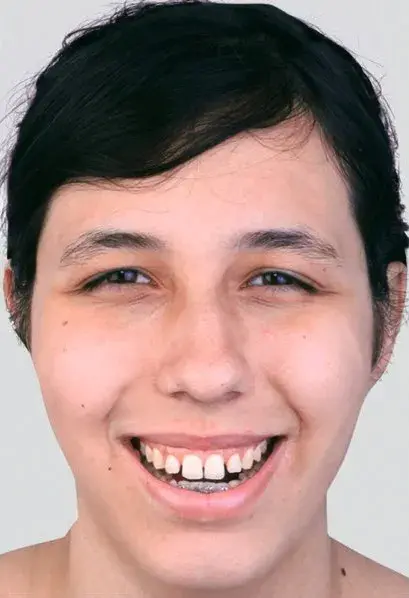

A 16-year-old female patient frustrated with her smile presented to the authors’ private practice complaining of EGD when smiling. She was a candidate for orthodontic treatment and a maxillary intrusion, as can be observed from the patient photographs in Figures 1 to 3 as well as the cephalometric analysis. The patient presented EGD of approximately 8 mm during maximum smile, and an overjet of 8 mm. The cephalometric examination helped to diagnose the patient’s EGD as skeletal in etiology. The VME and increased interlabial distance can be observed on the cephalometric radiograph (Fig 2a).

During the clinical examination, 12.8 mm of lip displacement and 8.5 mm of gingival exposure were observed during smiling, which led to a diagnosis of a hyperactive upper lip. Tooth evaluation revealed short clinical crowns in the maxillary anterior region. In addition, probing showed that the alveolar crest was located 2 to 3 mm apical of the cementoenamel junction, leading to a diagnosis of APE. The final diagnosis was EGD due to a combination of APE, VME, and a hyperactive upper lip.

Orthognathic surgery was recommended; however, the patient did not accept this treatment option due to the significant surgical involvement and because she desired a minimally invasive treatment. Thus, an alternative treatment plan was proposed.

Fig 1 Frontal facial photograph showing excessive gingival display during spontaneous smiling.

Fig 1 Frontal facial photograph showing excessive gingival display during spontaneous smiling.

Fig 2 (a) Lateral cephalometric radiograph. (b and c) Profile photographs.

Fig 2 (a) Lateral cephalometric radiograph. (b and c) Profile photographs.

Digital Smile Planning

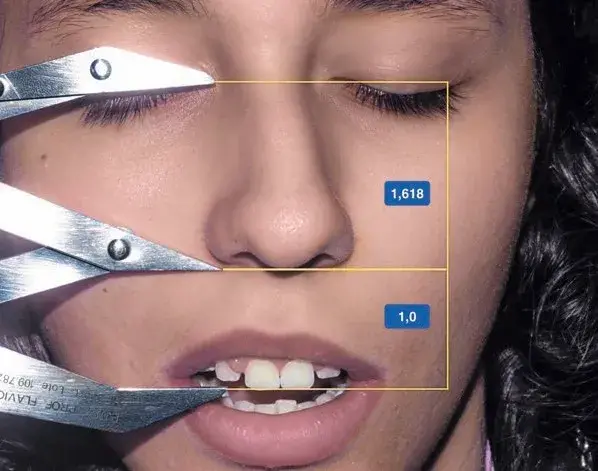

There was no discrepancy found when analyzing the vertical golden proportion, and occlusal guidance was normal and integrated with the stomatognathic system (Figs 4 to 6). Therefore, the patient’s face was determined to be in harmony as per the maxillary incisal edge measurement using the corner of the eye, nose base height, and incisal edge of the central incisor as references (Fig 7).[9,10] In this case, periodontal surgery was the clinical approach determined to improve the esthetics and the cervicoincisal length of the involved teeth. No endodontic treatment was required.

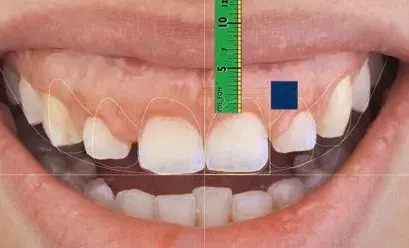

After photographic documentation was completed, the photos were exported to computer software (Keynote; Apple) and a digital rule was used to determine the central incisor proportion (Fig 8). Utilizing the width:height ratio of the maxillary central incisor, it is possible to define the format of the teeth; proportions between 75% and 85% are the most accepted values in the literature.[19] The proportion of 85% was chosen as it would require the least invasive treatment, with less removal of the alveolar bone crest required to increase the crown length during periodontal surgery. Furthermore, the digital design was shown to the patient, who also preferred the 85% proportion. Thus, DSP was completed according to established proportions obtained through mesial, distal, and cervicoincisal measurements (Fig 9).

Fig 3 Initial photograph of the pretreatment condition.

Fig 3 Initial photograph of the pretreatment condition.

Fig 4 Anterior occlusal guidance.

Fig 4 Anterior occlusal guidance.

Fig 5 Left lateral occlusal guidance.

Fig 5 Left lateral occlusal guidance.

Fig 6 Right lateral occlusal guidance.

Fig 6 Right lateral occlusal guidance.

Fig 7 Vertical face proportions.

Fig 7 Vertical face proportions.

Fig 8 Determination of the central incisor proportion, measurement of 5 mm of gingival exposure, and plan to increase the dental crown by 3 mm.

Fig 8 Determination of the central incisor proportion, measurement of 5 mm of gingival exposure, and plan to increase the dental crown by 3 mm.

Fig 9 Selection of tooth format, with tooth shape selection based on face shape and final crown size planning.

Fig 9 Selection of tooth format, with tooth shape selection based on face shape and final crown size planning.

Based on 2D digital planning measures, a conventional diagnostic wax-up from the second right premolar to the second left premolar was created (Figs 10 and 11). A mock-up with bis-acryl resin (Systemp C&B II; Ivoclar Vivadent) was fabricated that respected the occlusal guidance and allowed the patient to visualize and understand the treatment (Fig 12). The proposed treatment, which was approved by the patient, consisted of orthodontic therapy, crown lengthening surgery, BTX type A injections to reduce the extent of the gingival display, and 10 maxillary ceramic restorations to establish a new dental anatomy.

Orthodontic treatment was the first treatment step and was performed to align the midline between the maxillary and mandibular arches. After 8 months, the alignment was completed, and an orthodontic contention was made.

The treatment of the excessive gingival display was carried out with crown lengthening surgery with osteotomy, and a papilla preservation technique was performed (Fig 13–14). A surgical template was digitally defined during the DSP, based on the chosen tooth measurements and verified with the mock-up. Approximately 1.6 mm of gingival tissue was removed, and a new distance from the gingival margin to the alveolar bone crest of approximately 2.74 mm was established with osteotomy. There was a 6-month waiting period for periodontal tissue healing before dental preparation procedures were initiated (Fig 15).

The next clinical procedure for the management of the EGD was the application of BTX type A (Dysport; Ipsen).[14,21,22] Diluted according to the manufacturer’s recommendations and under sterile conditions, 6 IU of BTX type A was injected once per side to target the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi, zygomaticus minor, and levator labii superioris muscles (Fig 16).

Fig 10 Digital Smile Planning measures transferred to the plaster cast before diagnostic waxing.

Fig 10 Digital Smile Planning measures transferred to the plaster cast before diagnostic waxing.

Fig 11 Conventional wax-up according to the initial digital planning.

Fig 11 Conventional wax-up according to the initial digital planning.

Fig 12 (a to c) Mock-up of the final rehabilitation format.

Fig 12 (a to c) Mock-up of the final rehabilitation format.

Fig 13 (a to c) Crown lengthening procedure

Fig 13 (a to c) Crown lengthening procedure

Fig 14 Immediate postoperative photograph after periodontal surgery based on final dental crown size planning.

Fig 14 Immediate postoperative photograph after periodontal surgery based on final dental crown size planning.

Fig 15 Postoperative photograph after periodontal surgery showing the increased clinical crown before the application of botulinum toxin (BTX) type A.

Fig 15 Postoperative photograph after periodontal surgery showing the increased clinical crown before the application of botulinum toxin (BTX) type A.

Fig 16 (a and b) Views after the application of BTX type A to control upper lip hyperactivity and bleaching with 16% carbamide peroxide.

Fig 16 (a and b) Views after the application of BTX type A to control upper lip hyperactivity and bleaching with 16% carbamide peroxide.

Prosthetic treatment

Before tooth preparation and veneer placement, dental bleaching was performed using carbamide peroxide (Total Blanc Home C16; DFL) for 10 days, with the goal of achieving a more favorable substrate. Silicone wear guides were produced from the mock-up to ensure minimally invasive tooth preparations for the ceramic veneers. A retraction cord (Ultrapak; Ultradent) was placed in the sulcus to allow the preparation to reach the gingival margin level. Rotary instruments (no. 6863-012 diamond tips and no. H48L bur; Komet), abrasive rubber points (Astropol Polishing System; Ivoclar Vivadent), and a polish brush point (Astrobrush Polishing System; Ivoclar Vivadent) were used for the polishing procedures (Fig 17). Tooth preparation followed the silicone guides.

After this process, a retraction cord with a larger diameter (size 00) was placed above the original, small-diameter cord (size 000) and an impression was made using an addition-cured silicone (Virtual Putty Base Set; Ivoclar Vivadent). To conclude this appointment, the shade of the teeth was selected (Vita Classical; Vita Zahnfabrik), and interim prostheses were fabricated with a bis-acryl resin-based material from the silicone index.

The impression was sent to the dental laboratory technician and the cast was scanned. The wax-up was also scanned and the images were overlaid (Ceramill Map 200+; Amann Girrbach) (Fig 18). The data were then sent to a milling machine that performed stratification of the e.max CAD (IPS e.max CAD CEREC inLab LT BL3/C14; Ivoclar Vivadent).

During the cementing appointment, the ceramic veneers were conditioned with 10% hydrofluoric acid (Hydrofluoric Acid Porcelain Etchant; Maquira) for 20 s, washed, air dried, cleaned with 35% phosphoric acid (Ultra-Etch IndiSpense; Ultradent) for 60 s, and coated with a silane layer (Monobond N; Ivoclar Vivadent). Each tooth was etched with phosphoric acid for 30 s, washed for the same amount of time, and then a layer of dental adhesive (Adper Scotchbond; 3M ESPE) was applied. The restorations were seated with resin cement (Variolink Esthetic; Ivoclar Vivadent) and photoactivated for 40 s per tooth (Bluephase; Ivoclar Vivadent). The right and left lateral occlusal guidance were checked (Fig 19). The final completed treatment with increased clinical crown, application of BTX type A, and ceramic veneers are shown in Figures 20 and 21.

Fig 17 Minimally invasive dental preparation for the ceramic veneers.

Fig 17 Minimally invasive dental preparation for the ceramic veneers.

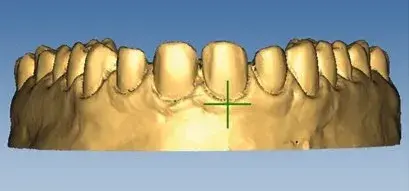

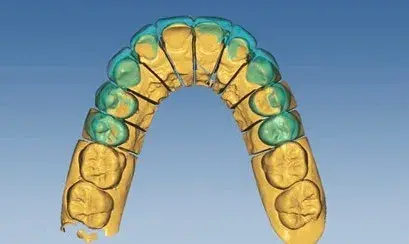

Fig 18 (a to c) Images of scanned preparation and wax-up in Ceramill Map 200+ software.

Fig 18 (a to c) Images of scanned preparation and wax-up in Ceramill Map 200+ software.

Fig 19 Testing right (a) and left (b) lateral occlusal guidance.

Fig 19 Testing right (a) and left (b) lateral occlusal guidance.

Fig 20 Completed treatment with increased clinical crown, application of BTX type A, and ceramic veneers.

Fig 20 Completed treatment with increased clinical crown, application of BTX type A, and ceramic veneers.

Fig 21 Frontal facial photograph after completed treatment

Fig 21 Frontal facial photograph after completed treatment

Discussion

EGD is a nonpathologic condition in which there is an overexposure of the maxillary gingiva during smiling.[12] The potential causes of EGD are short lip length, hypermobile/hyperactive lip activity, short clinical crown, dentoalveolar extrusion, APE, VME, and gingival hyperplasia.[11] Proper diagnosis of the etiologic factors determines the most appropriate treatment technique, taking into consideration patient preferences.[12,22,23] In the present case, the patient was diagnosed with APE, VME, and a hyperactive upper lip. The indicated treatment for VME is orthognathic surgery.[16] However, as this procedure requires hospitalization, some patients are unwilling to undergo these more invasive surgeries[18] and, consequently, welcome alternative treatments.

The success of any dental treatment is based on correct diagnosis, planning, execution, and monitoring. Thus, tools that aid the dentist in organizing the collected diagnostic information and transferring it to treatment possibilities are fundamental. Indeed, the DSP method is not applicable for tooth standardization, but instead is a tool to be individually applied taking into consideration the patient’s needs and expectations in order to create harmony between the face and mouth. A distinguishing characteristic of the DSP technique is that it considers the vertical golden ratio as a reference for smile design.[9,24] After the diagnosis and planning phases, the treatment options with their advantages and disadvantages were presented to the patient and her parents, and the describe treatment was chosen.

EGD is dominated by the excessive contraction of the levator labii superioris muscles. BTX is used to mask gingival exposure with success in patients with lip hyperactivity, as in lip repositioning surgery.[13,14,19] Although the BTX injection is a nonsurgical and minimally invasive treatment option, the results are temporary and necessitate frequent reapplications.[14] It has been demonstrated that patients treated with BTX type A presented with higher levels of satisfaction when the lip repositioning surgical technique and BTX injection were compared.

Regarding the prosthetic treatment phase, it is important to note that alternatives, including direct restorations with composite resins and ceramic laminates, were presented with the pros and cons of each, and the treatment option using ceramic veneers was chosen.

Thus, the selection of the restorative material considered the preference of the patient and her family, the experience of the dentist and the dental laboratory technician, and the scientific evidence, ie, the fundamental tripod of evidence-based dentistry was respected.[26]

The term ‘veneer’ refers to the prosthetic itself, which can be made: a) without the need for dental preparation (also known as ‘prepless’ and limited to very specific cases); b) with uniform tooth preparation guided by the shape of the diamond burs (the traditional tooth preparation, which is very aggressive); or c) with selective tooth preparation (guided by previous planning and silicone-based guides).[27] The last option was selected in this case. In addition to the advantage of the preparation being very subtle, this approach allows for a more uniform prosthetic piece, which is desirable when a ceramic material is employed. Furthermore, the prepless technique is associated with the use of feldspar-based ceramic made with excess that is later removed in the finishing/polishing process. Unfortunately, this process can cause invasion of the periodontal space when performed close to this region and can thus result in severe injuries.[28]

You have the opportunity to gather more in-depth information about digital smile design in August de Oliveira course "Digitalize the Dental Сlinic: A Complete Guide to Designing and 3D Printing".

Conclusion

The present clinical report described how the DSP technique, through precise photographs and based on the golden ratio applied to vertical face proportions, can assist the dentist in planning a conservative treatment.

The case involved the oral rehabilitation of a patient with EGD using alternative treatments to orthognathic surgery, including crown lengthening surgery, ceramic veneers on 10 maxillary teeth, and the application of BTX type A to reduce lip hyperactivity.

List of authors:

Flavio Queiroz Henriques, Karinne Bueno Antunes, Gabriella Castro de Sousa, Lucio Macedo de Menezes Filho, Luis Felipe Jochims Schneider, Larissa Maria Cavalcante

References

Larsson P, Bondemark L, Häggman-Henrikson B. The impact of oro-facial appearance on oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil 2021;48:271–281.

Spagnuolo G, Sorrentino R. The role of digital devices in dentistry: clinical trends and scientific evidences. J Clin Med 2020;9:1692.

Coachman C, Calamita M, Ricci A. Digital Smile Design: A Digital Tool for Esthetic Evaluation, Team Communication, and Patient Management, ed 3. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2018:85–111.

Sanchez-Lara A, Chochlidakis KM, Lampraki E, Molinelli R, Molinelli F, Ercoli C. Comprehensive digital approach with the Digital Smile System: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2019;121:871–875.

Kalia R. An analysis of the aesthetic proportions of anterior maxillary teeth in a UK population. Br Dent J 2020;228:449–455.

Ward DH. Proportional smile design: Using the recurring esthetic dental proportion to correlate the widths and lengths of the maxillary anterior teeth with the size of the face. Dent Clin North Am 2015;59:623–638.

Patnaik VVG, Singla, RK, Bala, S. Anatomy of a beautiful face and smile. J Anat Soc India 2003;52:74–80.

Coachman C, Paravina RD. Digitally enhanced esthetic dentistry – from treatment planning to quality control. J Esthet Restor Dent 2016;28(suppl 1):S3–S4.

Ricketts RM. The golden divider. J Clin Orthod 1981;15:752–759.

Silva MAS, Médici Filho M, Castilho JCM, Gil CTLA. Assessment of divine proportion in the cranial structure of individuals with Angle Class II malocclusion on lateral cephalograms. Dental Press J Orthod 2012:88–97.

Arias DM, Trushkowsky RD, Brea LM, David SB. Treatment of the patient with gummy smile in conjunction with digital smile approach. Dent Clin North Am 2015;59:703–716.

Antoniazzi RP, Fischer LS, Balbinot CEA, Antoniazzi SP, Skupien JA. Impact of excessive gingival display on oral health-related quality of life in a Southern Brazilian young population. J Clin Periodontol 2017;44:996–1002.

Sahoo KC, Raghunath N, Shivalinga BM. Botox in gummy smile – a review. Indian J Dent Sci 2012;1:51–53.

Duruel O, Ataman-Duruel ET, Tözüm TF, Berker E. Ideal dose and injection site for gummy smile treatment with botulinum toxin-A: a systematic review and introduction of a case study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2019;39:e167–e173.

Gup J, Gong H, Tian W, Tang W, Bai D. Alteration of gingival exposure and its aesthetic effect. J Craniofac Surg 2011;22:909–913.

Dym H, Pierre R 2nd. Diagnosis and treatment approaches to a “gummy smile”. Dent Clin North Am 2020;64:341–349.

Silberberg N, Goldstein M, Smidt A. Excessive gingival display – etiology, diagnosis, and treatment modalities. Quintessence Int 2009;40:809–818.

Gabrić Pandurić D, Blašković M, Brozović J, Sušić M. Surgical treatment of excessive gingival display using lip repositioning technique and laser gingivectomy as an alternative to orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014; 72:404.

Borges ACG, Seixas MR, Machado AW. Influence of different width/height ratio of maxillary anterior teeth in the attractiveness of gingival smiles. Dental Press J Orthod 2012;17:115–122.

Abou-Arraj RV, Majzoub ZAK, Holmes CM, Geisinger ML, Geurs NC. Healing time for final restorative therapy after surgical crown lengthening procedures: a review of related evidence. Clin Adv Periodontics 2015;5:131–139.

Mazzuco R, Hexsel D. Gummy smile and botulinum toxin: A new approach based on the gingival exposure area. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;63:1042–1051.

Aly LA, Hammouda NI. Botox as an adjunct to lip repositioning for the management of excessive gingival display in the presence of hypermobility of upper lip and vertical maxillary excess. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2016;13:478–483.

Tatakis DN, Gibson MP. Treatment of gummy smile of multifactorial etiology: a case report. Clin Adv Periodontics 2017;7:167–173.

Ricketts RM. Divine proportion in facial esthetics. Clin Plast Surg 1982:9:401–422.

Makkiah MO. Assessment of the efficiency of botox and lip reposition in the correction of the gummy smile according to the patients’ satisfaction. Oral Health Dental Sci 2017;1:1–4.

Bauer J, Chiappelli F, Spackman S, Prolo P, Stevenson R. Evidence-based dentistry: fundamentals for the dentist. J Calif Dent Assoc 2006;34:6:427–432.

Bichacho N. Porcelain laminates: integrated concepts in treating diverse aesthetic defects. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent 1995:7:13–23.

Lobo M, de Andrade OS, Barbosa JM, Hirata R. Periodontal considerations for adhesive ceramic dental restorations: key points to avoid gingival problems. Int J Esthet Dent 2019:14:444–457.