To Splint Or Not To Splint Short Dental Implants Under The Same Partial Fixed Prosthesis? One-Year Post-Loading Data From A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial

Purpose: To compare the clinical outcomes of two adjacent 6-mm-long dental implants splinted under the same prosthesis (control group) versus two identical implants supporting single crowns (test group).

Materials and methods: Forty-seven patients with edentulous posterior (premolars and/or molars) jaws received two adjacent 6-mm-long dental implants, which were submerged. Four months later, at impression taking, patients were randomised to receive splinted or unsplinted definitive cemented metal-composite prostheses. Unfortunately, four patients died before randomisation and three patients lost five implants, so only 40 patients were randomised, according to a parallel-group design, to have both implants splinted under the same partial fixed prosthesis (19 patients) or with two single crowns (21 patients). Outcome measures were: prosthesis and implant failures, any complications, peri-implant marginal bone level changes and patient satisfaction. Patients were followed-up to 1 year after loading.

Results: One patient from the splinted group dropped out. No implant failures occurred after randomisation. One complication occurred in the unsplinted group versus no complications at splinted implants, the difference not being statistically different (Fisher’s exact test P = 1.000; difference in proportions = -0.04; 95% CI -0.16 to 0.09). Both groups presented significant peri-implant marginal bone loss at 1 year after loading (P<0.05), respectively -0.36 (0.45) mm at splinted implants and -0.17 (0.31) mm at unsplinted implants, but there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups (mean difference 0.19 mm; 95% CI -0.10 to 0.48; P = 0.194). All patients were fully or reasonably satisfied with the treatment, with the exception of two patients, both from the splinted group: one patient was not sure about the aesthetics, and another would not undergo the same treatment again.

Conclusions: The present data seems to suggest that up to 1 year after loading the prognosis of short implants, mostly placed in mandibles characterised by dense bone quality, may not be influenced by splinting or not under the same fixed prostheses. However, these preliminary results need to be confirmed by larger trials with follow-ups of at least 5 years.

Introduction

Short dental implants (4 to 8 mm long) have been reported as an appealing and less invasive alternative to bone augmentation procedures for placing longer implants, with both groups displaying similar results up to 11 years after loading.

One of the issues often debated is whether it is better or not to join two or more short implants under the same prosthesis to decrease the potential risks of failures or mechanical complications such as screw loosening. Theoretically, it would be logical to think that joining short implants under the same fixed prosthesis would provide a more favourable load distribution. Unfortunately, there have been no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating this hypothesis thus far, so only opinion-based recommendations can be given.

The aim of this RCT of parallel-group design was to compare the clinical outcomes of two adjacent 6-mm-long dental implants splinted under the same prosthesis (control group) versus two identical implants, each supporting single crowns (test group). The test hypothesis was that there would be no differences between the two procedures, against the alternative hypothesis of a difference. This report presents data up to 1 year after loading (at the protocol stage we decided to follow the patients up to 5 years after loading). The present article is reported in accordance with the CONSORT statement for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials (http://www.consort-statement.org/).

Materials and methods

Study design

This trial was designed as a multicentre randomised controlled trial of parallel-group design with blind assessment, with the exception of complications and related failures, which were evaluated by the treating dentists.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Any patient with partial edentulism in the posterior jaw (premolars and/or molars), requiring at least two adjacent dental implants of length 6 mm and diameter of 5 mm, being 18 years or older and able to understand and sign informed consent was eligible for inclusion in this trial. Patients were not admitted to the study if any of the following exclusion criteria applied:

- General contraindications to implant surgery;

- Irradiation in the head and neck area;

- Immunosuppressed or immunocompromised status;

- Previous or ongoing treatment with intravenous aminobisphosphonates;

- Untreated periodontitis;

- Poor oral hygiene and motivation;

- Uncontrolled diabetes;

- Pregnancy or lactation;

- Substance misuse;

- Psychiatric problems or unrealistic expectations;

- Lack of opposite occluding dentition/prosthesis in the area intended for implant placement;

- Acute/chronic infection/inflammation in the area intended for implant placement;

- Participation in other trials, if precluding proper adherence to the present protocol;

- Referral for implant placement alone (unavailable for prosthetic procedures and/or follow-ups at the treating centre);

- Extraction sites with less than 3 months of healing;

- Unavailability for 5 years of follow-up.

Patients were categorised into three groups according to their declarations: non-smokers, moderate smokers (up to 10 cigarettes per day), and heavy smokers (more than 10 cigarettes per day). Patients were recruited and treated in eight different private practices in Italy using similar procedures, and each centre was supposed to treat 10 patients. Participating dentists (centres) were the following: Dr. Marco Tallarico in Rome (MT), Dr. Fulvio Gatti in Parabiago (FG), Dr. Mario Silvio Meloni in Arzachena (SM), Dr. Leonardo Muzzi in Siena (LM), Dr. Nicola Baldini in Florence (NB), Dr. Armando Minciarelli in Bari (AM), Dr. Gaetano Iannello in Terme Vigliatore (GI), and Dr. Mauro Billi in Montevarchi (MB).

Patients were assessed to establish their eligibility for the study; a preoperative cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan was obtained for each potentially eligible patient to quantify bone volumes at the planned implant sites. Patients having sufficient bone volumes to receive two 6-mm long, 5-mm wide implants at two adjacent sites were invited to join the study, and were informed of the nature of the study. Only after they fully understood the study aims and procedures were they asked to sign informed written consent.

Clinical procedures

About 10 days prior to implant placement, all patients were subjected to professionally delivered oral hygiene procedures, including debridement as required. One hour prior to implant placement, all patients received prophylactic antibiotic therapy: 2 g of amoxicillin, unless allergic to penicillin, in which case clindamycin 600 mg. All patients rinsed with chlorhexidine mouthwash 0.2% for 1 minute prior to any surgical procedure, and were treated under local anaesthesia using articaine with adrenaline 1:100.000. After crestal incision and full-thickness flap elevation, the two adjacent implant sites were prepared under prosthetic guidance using a surgical template. The standard placement procedure was adopted as recommended by the manufacturer. Drills of increasing diameters were used to prepare the implant sites. Bone quality was subjectively reported as hard, medium and soft. The handpiece motor was set at a torque of 25 Ncm during implant insertion. The implants used were OSSTEM IMPLANT TSIII SA (Seoul, South Korea); these are 6-mm-long, 5 mm in diameter tapered self-tapping implants with internal connection (TS3S5005S) made of grade 4 titanium with a surface alumina-blasted and acid-etched. Implants were placed at the crestal level with their coronal portion flush to the surrounding bone. Cover screws were placed, implants were submerged, and flaps closed with Vicryl 4.0 sutures. Baseline periapical radiographs of the study implants were taken using the paralleling technique. If the peri-implant marginal bone levels were unreadable or difficult to assess, a new radiograph was to be taken. Ibuprofen 400 mg was prescribed to be taken two to four times a day during meals, as long as required. In case of allergy or stomach problems, 1 g paracetamol was prescribed instead. Patients were instructed to use 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash for one minute twice a day for 2 weeks, to adhere to a soft diet for one week, and to avoid brushing and trauma to the surgical sites. No removable denture which could load the study implants was allowed for one month. Sutures were removed after 7–10 days.

After 4 months of submerged healing, implants were exposed and manually tested for stability using 30 Ncm torque. Impressions with screw-retained pick-up impression copings were taken at implant level using a polyether material (ImpregumTM, 3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany) and customised open impression trays. Healing abutments were placed, and patients were randomised, according to a parallel-group design, to receive either a fixed partial prosthesis rigidly connecting the two adjacent implants (splinted group; Figs. 1A-G) or two single crowns (unsplinted group; Figs. 2A-G), by opening the sequentially numbered envelope corresponding to the patient recruitment number.

Within one month, after having tested the stability of the individual implants, either definitive cement-retained metal-composite crowns or fixed partial prostheses rigidly joining the two implants were cemented with provisional cement (ImplaCem Automix, Dentalica, Milan, Italy) on Osstem transfer abutments for cement-retained restoration, according to the random allocation. Abutments were customised in the lab when necessary. The occlusal surfaces were in slight contact with the opposing dentition. Periapical radiographs and clinical pictures of the study implants were taken. If the peri-implant marginal bone levels were not readable, a new radiograph was to be taken. Oral hygiene instructions were delivered.

One month later, patients were recalled for a check-up and to evaluate their satisfaction. Patients were enrolled in an oral hygiene programme with recall visits at least every 6 months for the entire duration of the study. Dental occlusion was evaluated at each follow-up visit. Follow-ups were conducted by local independent outcome assessors together with the surgical operators.

Outcome measures

This study tested the null hypothesis that there would be no differences between the two procedures against the alternative hypothesis of a difference.

Outcome measures were the following.

- Prosthesis failures: loss of the prosthesis secondary to implant failure(s), or replacement of the prosthesis for any reason.

- Implant failures: implant mobility, removal of stable implants dictated by progressive marginal bone loss or infection, or any mechanical failure rendering the implant unusable, such as implant fracture or deformation of the implant–abutment connection. Stability of individual implants was measured by local independent assessors, who were not informed of the nature of the study, manually tightening the screws with 30 Ncm torque at abutment connection (4 months after implant placement), initial loading (1 month after delivery of the provisional prostheses), and 1 year after loading for the partial fixed prostheses. Once single crowns were cemented, their stability was assessed by rocking the crown with the metal handles of two dental instruments.

- Any biological or prosthetic complication was reported.

- Peri-implant marginal bone level changes, evaluated on intraoral digital radiographs taken with the paralleling technique at implant placement, at initial loading, and one year after loading. In the case of less than properly readable radiographs, new radio- graphs were to be taken. A centralised outcome assessor (Dr. Erta Xhanari, EX) measured peri-implant marginal bone levels using Scion Image (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD, USA) software. The software was calibrated for each single image using the known distance between the first two consecutive coronal threads. Measurements of the mesial and distal bone crest levels adjacent to each implant were made to the nearest 0.01 mm. Reference points for the linear measurements were the coronal margin of the implant collar and the most coronal point of bone-to-implant contact. Implants with bone up to the coronal margin of the implant collar were assigned a value of zero. The mesial and distal measurements of each implant were averaged, and means were calculated at patient level and then at group level.

- Patient satisfaction: at one year after loading, the independent outcome assessor at each centre asked the patients the following questions: “are you satisfied with the function of your implant-supported prosthesis?” and “are you satisfied with the aesthetic outcome of your implant-supported prosthesis?”. Possible answers were: “yes, absolutely”, “yes, partially”, “not sure”, “not really”, and “absolutely not”. Patients were also asked “would you undergo the same therapy again?”; possible answers were: “yes” or “no”.

One independent assessor at each centre, masked to the interventions, took all measurements, with the exception of complications and some failures, which were managed and reported directly by the treating dentist. One single centralised outcome assessor (EX), not involved in the treatment of the patients, measured all peri-implant marginal bone levels without knowing group allocation. However, it was possible to discriminate between single crowns and partial fixed prostheses on the radiographs.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated for the primary outcome measures (implant failure): a two-group continuity-corrected chi-square test with a 0.050 two-sided significance level will have 80% power to detect the difference between a proportion of 0.100 and a proportion of 0.300 for patients experiencing at least one implant failure (odd’s ratio of 3.857) when the sample size in each group is 72. However, it was decided to include only 40 patients in each group, since that was our realistic recruitment capacity over a 2-year recruitment period. Eight computer-generated restricted randomisation lists were created. Only one of the investigators (Dr. Marco Esposito, ME), not involved in the selection and treatment of the patients, was aware of the randomisation sequence and could have access to the randomisation lists, which were stored on his password-protected laptop. The randomisation codes were enclosed in sequentially numbered, identical, opaque, sealed envelopes. Envelopes were opened sequentially after impression-taking, and treatment allocation was therefore concealed to the investigators in charge of enrolling and treating the patients.

All data analysis was carried out according to a pre-established analysis plan. The patient was the statistical unit of the analyses. A dentist with expertise in statistics (Dr. Jacopo Buti, JB) analysed the data without knowing group allocation. Differences in the proportions of patients with prosthesis failures, implant failures and complications (dichotomous outcomes) were compared between groups using Fisher’s exact probability test, and between centres using the Freeman-Halton extension of Fisher’s exact test (when cell count was <5). Paired t-tests were used to compare the mean radiographic values at implant placement, initial loading, and 1 year after loading. Unpaired t-tests were used to compare the mean radiographic marginal bone level changes between groups. Comparisons of function and aesthetic satisfaction between groups and centres were done using Fisher’s exact probability test and the Freeman-Halton extension of Fisher’s exact test (when cell count was <5), respectively, as outcomes reported fell only into 2 (fully vs. partially satisfied) out of the 5 categories (with the exception of one patient who was “not sure” and was grouped together with the “not fully satisfied” patients). Fisher’s exact probability test was used to compare the willingness of groups to undergo the same intervention again. All statistical comparisons were conducted at the 0.05 level of significance. An intention-to-treat analysis was applied.

Results

Forty-seven patients were considered eligible and consecutively enrolled in the trial. Patients were recruited and treated from November 2016 to January 2018. The follow-up of all patients was 1 year after implant loading. Each centre was supposed to enrol 10 patients, who were to be randomised into two equal groups of five patients each. However, only one centre (MT) recruited 10 patients. The remaining centres recruited nine patients (FG and SM), seven patients (NB), six patients (LM), four patients (AM) and one patient (MB and GI), respectively. Five additional patients were screened for eligibility at three centres, but were not interested in participating in the trial. Unfortunately, four patients died or became comatose during the trial, and a further three patients lost five implants after implant placement but before randomisation and loading.

Forty patients should have been allocated to each group, but due to under-recruitment and premature death or coma (four patients) and implants failures before loading (three patients) only 19 patients were randomised to the splinted group, and 21 patients to the single crown group.

Reasons for death/coma were the following. To be randomised to the splinted group:

- Died due to stroke before impression-taking and delivery of final restoration.

To be randomised to the unsplinted group:

- Died due to cardiac ischaemia before impression-taking;

- Dropped out before impression-taking due to coma after car accident;

- Died before impression-taking due to cardiac ischemia followed by nosocomial lung infection and septicaemia.

The following protocol deviations were recorded:

- All centres used metal ceramic prostheses instead of the metal-composite prostheses required by the research protocol.

Unsplinted group

- Two patients received screw-retained disilicate crowns instead of metal-composite ones.

- One patient lost one implant before loading and refused to have it replaced, so a prosthesis supported by the remaining short implant and another previously inserted implant was delivered, and the patient was no longer included in the study.

- For two patients, no periapical radiographs (baseline, loading or 1 year after loading) were taken.

- For one patient, a panoramic radiograph instead of a periapical radiograph was taken at baseline, and a periapical radiograph was not taken at loading.

- For one patient, panoramic radiographs instead of periapical radiographs were taken at baseline and loading.

- For one patient, panoramic radiographs instead of periapical radiographs were taken at loading and 1 year after loading.

Splinted group

- For two patients, no periapical radiographs (baseline, loading or 1 year after loading) were taken.

- For one patent, at 1 year after loading, a panoramic radiograph instead of a periapical radiograph was taken.

One patient, from the splinted group, dropped out up to during the first year after loading, declaring that she was too busy to attend the 1-year follow-up because her daughter was getting married.

The data from all remaining patients were evaluated in the statistical analyses.

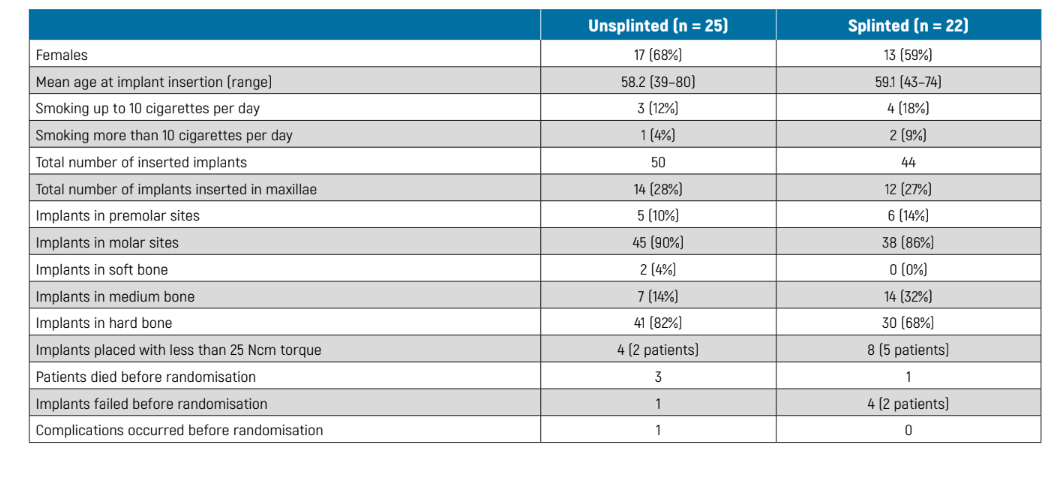

The main baseline patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were no significant imbalances apparent between the two groups at baseline.

Prosthesis failures

No delivered prosthesis actually failed, but two prostheses could not be placed due to early failures of both implants before loading; these patients were going to be randomised to the splinted group.

Implant failures

No implants failed after randomisation, but before randomisation and loading, one implant failed in the unsplinted group versus four implants in two patients from the splinted group. The implant that failed in the unsplinted group was in position 36; the patient had pain and swelling with purulent discharge. The implant was immediately removed 3 weeks after placement; the patient refused a replacement implant and instead a partial fixed prosthesis supported by the remaining short implant and a previously inserted implant was delivered. In the unsplinted group, two implants, in positions 36 and 37, were removed from one patient 4 weeks after their placement because of infection. A further two implants in the same patient, in positions 25 and 26, were found not to be osteointegrated at abutment connection.

Complications

One complication occurred in the unsplinted group versus no complications at splinted implants, the difference being not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test P = 1.000; difference in proportions = -0.04; 95% CI -0.16 to 0.09). The complication consisted of chipping of the ceramic veneer of the crown in position 15 at 1 year after loading, which was resolved chairside. Before randomisation and loading, another complication occurred: persistent pain for 4 weeks after implant placement at implants in positions 36 and 37, which spontaneously healed.

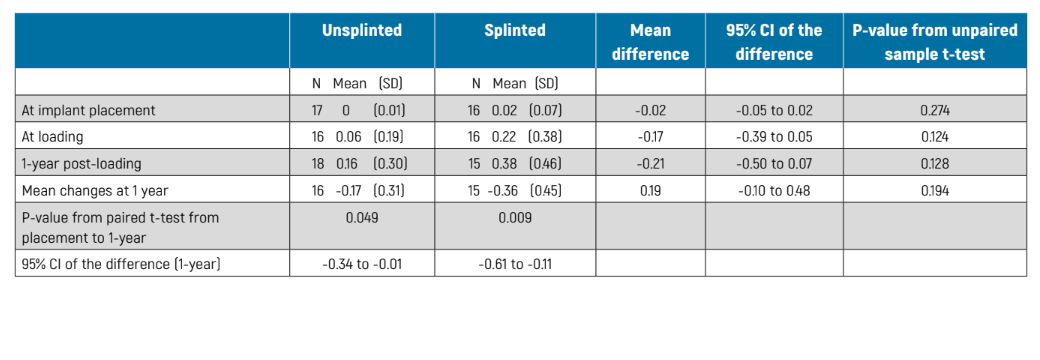

Peri-implant marginal bone level changes could be measured at all implant surfaces of the periapical radiographs. Measurements were not taken on panoramic radiographs. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in bone levels at implant placement, loading or 1 year after loading (Table 2). However, both groups gradually lost marginal peri-implant bone to a statistically significant degree (P <0.05) (Table 2). At 1-year post-loading, patients with unsplinted implants lost -017 ± 0.31 mm, as compared with -0.36 ± 0.45 mm for splinted implants, the difference between groups not being statistically significant (P = 0.194; mean difference 0.19 mm; 95% CI -0.10 to 0.48; Table 2).

Patient satisfaction

At one year after loading, all patients declared to the independent outcome assessors that they were highly satisfied with both the function and aesthetics of their implant-supported prostheses, with the exception of three patients from the splinted group (three partially satisfied with function, one who was partially satisfied with aesthetics, and another who was not sure) and one patient from the unsplinted group, who was partially satisfied with both function and aesthetics. Only one patient, from the splinted group, declared that she would not undergo the same treatment again. There were no statistically significant differences between groups for either function (difference in proportions = 0.12; 95% CI -0.10 to 0.32, P = 0.318), aesthetics (0.06; 95% CI -0.13 to 0.26, P = 0.586), or willingness to undergo the same intervention again (0.06; 95% CI -0.10 to 0.21, P = 0.462).

Comparison between different centres

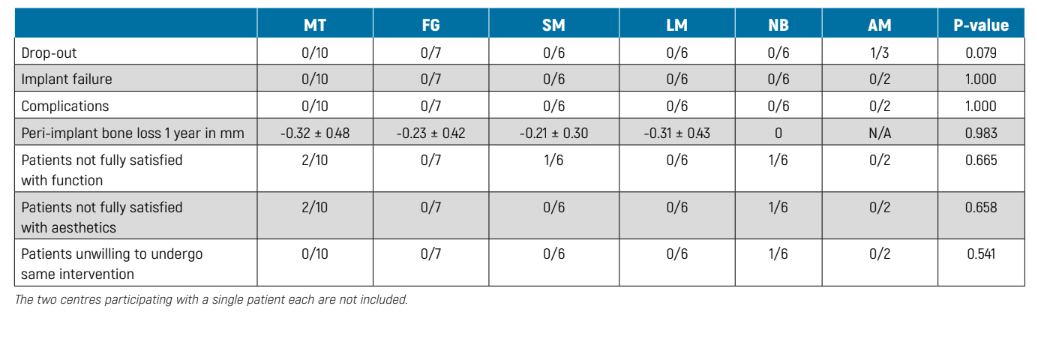

The two centres that treated one patient each were not considered for the purposes of these statistical analyses. There were no differences between the six remaining centres in any of the outcome measures (Table 3).

Discussion

This trial was designed to provide preliminary data on whether it would be more advisable to join two adjacent short implants under the same prosthesis or to restore them with single crowns instead. There is a general opinion that it could be preferable to join implants under the same prosthesis to decrease the risk of possible biomechanical complications. However, our very preliminary finding, based on a small study population, is that both prosthetic alternatives yield very similar clinical short-term results. Obviously, our findings must be confirmed by longer follow-ups (more than 10 years) and further studies with larger sample sizes. Since there have not yet been any other trials testing our hypothesis, it is difficult to compare our results with those of other, similar trials. The most relevant issue now is to evaluate the medium- and long-term outcome of these two prosthetics options and only longer follow-ups can answer this question.

In the meantime, an interesting observation that emerged from this study was that the majority of implants from both groups were inserted in bone subjectively judged at drilling by the clinicians as hard bone, meaning that it was felt to be composed of mostly cortical bone. This could be tentatively explained by two factors: 1) the majority of the implants were placed in posterior mandibles, and bone in mandibles tends to be denser than in maxillae; 2) jaws were quite atrophic, and this again makes the presence of areas characterised by dense cortical bone more common. This observation could also partly explain the positive outcome of the unsplinted single implant in the present study. However, to get a more complete representation of actual situation, trials focusing only on short implants splinted or not in the posterior maxilla should be conducted.

The main limitations of the present trial are the small sample size, the protocol deviations (missing radiographs and panoramic radiographs taken instead of periapical radiographs), which further reduced the sample size for radiographic evaluation, and the limited duration of this trial. Unfortunately, the planned sampled size, which would have been insufficient anyway, was not achieved since most of the centres did not recruit the number of patients agreed a priori. In addition, some patients died or had implant failures after implant placement but before being randomised.

Nonetheless, as and when data from other RCTs become available, it should be possible to combine our findings with those from similar trials in meta-analyses, thereby obtaining larger sample sizes on which to determine a more precise estimate of possible differences between the two techniques, if any. Regarding the short duration of the follow-up, it is hoped that all centres will continue to monitor this cohort of patients, since, if some differences between the two prosthetic solution exist, they might appear only after several years in function.

As regards the present study, however, both procedures were tested in real clinical conditions and patient inclusion criteria were rather broad, therefore the results of this investigation may be generalised with confidence to a wider population with similar characteristics, bearing in mind that the great majority of implants were placed in dense mandibular bone.

Conclusions

Our data seem to suggest that up to 1 year after loading the prognosis of short implants, mostly placed in mandibles characterised by dense bone quality, may not be influenced by splinting or not under the same fixed prostheses. However, these preliminary results need to be confirmed by larger trials with follow-ups of at least 5 years.

Marco Tallarico, Fulvio Gatti, Silvio Mario Meloni, Leonardo Muzzi, Nicola Baldini, Jacopo Buti, Armando Minciarelli, Erta Xhanari, Marco Esposito

References

- Renouard F, Nisand D. Impact of implant length and diameter on survival rates. Clinical Oral Implants Research 2006;17(2):35-51.

- Felice P, Barausse C, Pistilli R, Ippolito DR, Esposito M. Five-year results from a randomised controlled trial comparing prostheses supported by 5 mm long implants or by longer implants in augmented bone in posterior atrophic edentulous jaws. International Journal of Oral Implantology 2019;12:25-37.

- Felice P, Barausse C, Pistilli R, Buti J, Gessaroli M, Esposito M. Short implants versus bone augmentation for placing longer implants in atrophic maxillae. Five-year post-loading results of a randomised controlled trial. Clinical Trials in Dentistry 2020;2: In press.

- Felice P, Pistilli R, Barausse C, Piattelli M, Buti J, Esposito M. Posterior atrophic jaws rehabilitated with prostheses supported by 6 mm long 4 mm wide implants or by longer implants in augmented bone. Five-year post-loading results from a randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Oral Implantology 2019;12:57-62.

- Bolle C, Felice P, Barausse C, Pistilli R, Trullenque-Eriksson A, Esposito M. Four mm-long versus longer implants in augmented bone in posterior atrophic jaws: one year post-loading results from a multicentre randomised controlled trial. European Journal of Oral Implantology 2018;10:31-47.

- Gastaldi G, Felice P, Pistilli R, Barausse C, Trullenque-Eriksson A, Esposito M. Short implants as an alternative to crestal sinus lift: a 3-year multicentre randomised controlled trial. European Journal of Oral Implantology 2018;11:391-400.

- Cannizzaro G, Felice P, Minciarelli AF, Leone M, Viola P, Esposito M. Early implant loading in the atrophic posterior maxilla: 1-stage lateral versus crestal sinus lift and 8 mm hydroxyapatite-coated implants. A 5-year randomised controlled trial. European Journal of Oral Implantology 2013;6:13-25.

- Esposito M, Buti J, Barausse C, Gasparro R, Sammartino G, Felice P. Short implants versus longer implants in vertically augmented atrophic mandibles: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials with a 5-year post-loading follow-up. International Journal of Oral Implantology 2019;12:267-80.

- Esposito M, Barausse C, Pistilli R, Piattelli M, Di Simone S, Ippolito DR, Felice P. Posterior atrophic jaws rehabilitated with prostheses supported by 5x5 mm implants with a nanostructured calcium-incorporated titanium surface or by longer implants in augmented bone. Five-year results from a randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Oral Implantology 2019;12:39-54.

- Guljé FL, Raghoebar GM, Vissink A, Meijer HJA. Single crowns in the resorbed posterior maxilla supported by either 11-mm implants combined with sinus floor elevation surgery or by 6-mm implants: a 5-year randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Oral Implantology 2019;12:315-26.

- Thoma DS, Haas R, Sporniak-Tutak K, Garcia A, Taylor TD, Hammerle CHF. Randomized controlled multicentre study comparing short dental implants (6 mm) versus longer dental implants (11-15 mm) in combination with sinus floor elevation procedures: 5-year data. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 2018;45:1465-74.