Treating Peri-implantitis – Is it possible?

Machine translation

Original article is written in DE language (link to read it) .

Implants have long established themselves as a standard procedure. Both patients and practitioners appreciate their value and the ability to predictably restore edentulous areas of the jaw. New implant surfaces allow for use even in compromised situations with shorter healing times. It seems that there is no risk. Survival rates significantly above 95 percent are taken for granted. Is it really that simple? Is the implant a low-risk tool for treatment in everyday dentistry? Survival rates are not equivalent to success. Studies suggest that up to 65 percent of cases are affected by peri-implant mucositis and 47 percent by peri-implantitis. Early treatment of peri-implant mucositis and prevention of peri-implantitis is of utmost priority.

Diagnostics

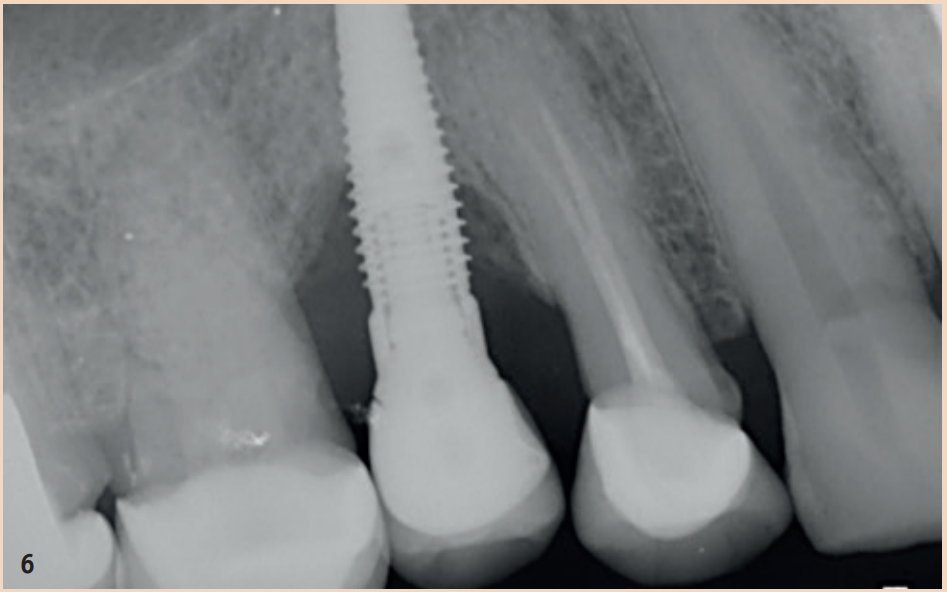

For the diagnosis of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis, only a periodontal probe and a single tooth radiograph are necessary.

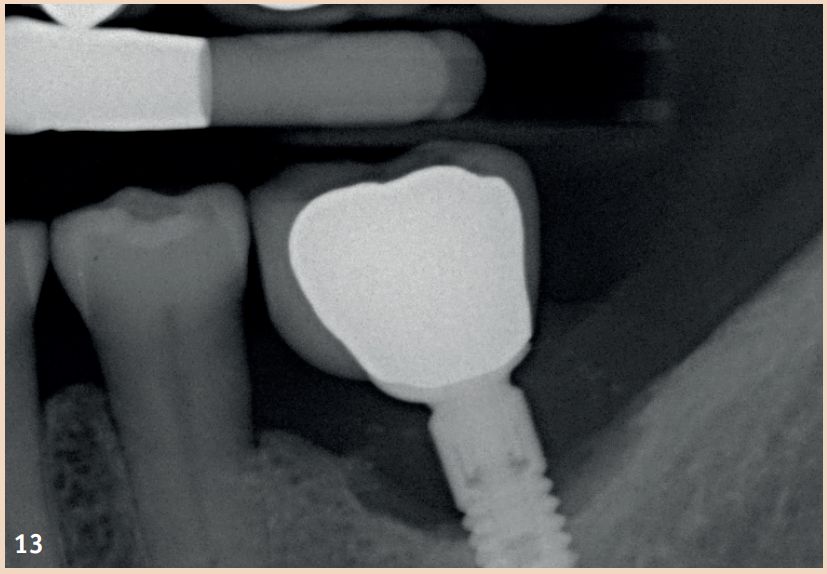

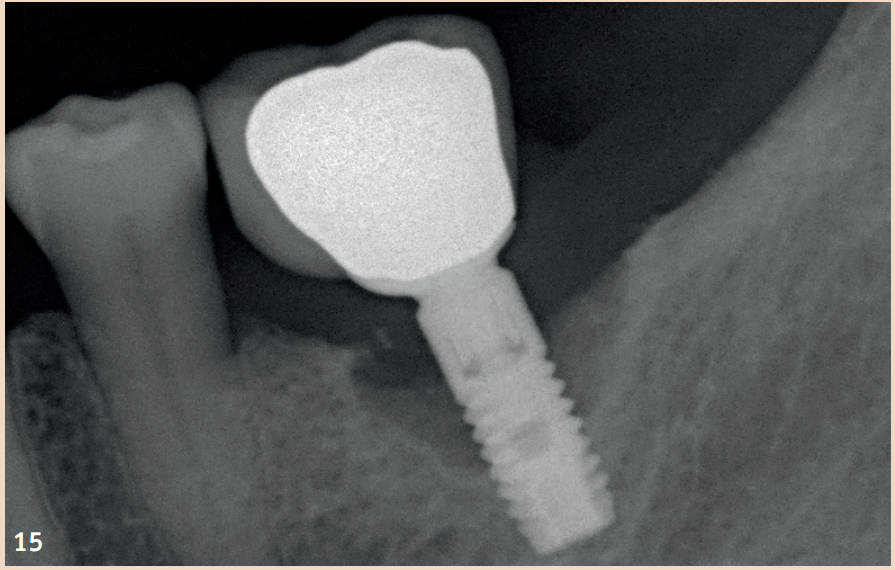

The regular probing of the peri-implant probing depths after the healing phase is recommended. The pressure should not exceed 0.25 N. The risk of damaging the implant surface during the probing process is unfounded, so conventional measuring probes do not need to be replaced by special measuring probes. Early detection of peri-implant mucositis is important, as the transition to peri-implantitis is gradual and the stage of the disease cannot currently be determined with any available tools. In addition to probing depths, Bleeding on Probing (BOP) is the focus, which gives the practitioner an initial insight into the inflammatory condition of the mucosa. While a positive BOP indicates at least peri-implant mucositis, suppuration is a sign of existing peri-implantitis. Literature indicates threshold values for bone loss between 0.4 mm and 5 mm, above which peri-implantitis can be diagnosed. There are also cases reported where bone loss of up to three screw threads was not considered peri-implantitis but still fell within the definition of peri-implant mucositis. However, these bone remodeling processes can only be recognized in X-rays and can be evaluated depending on the type of image taken.

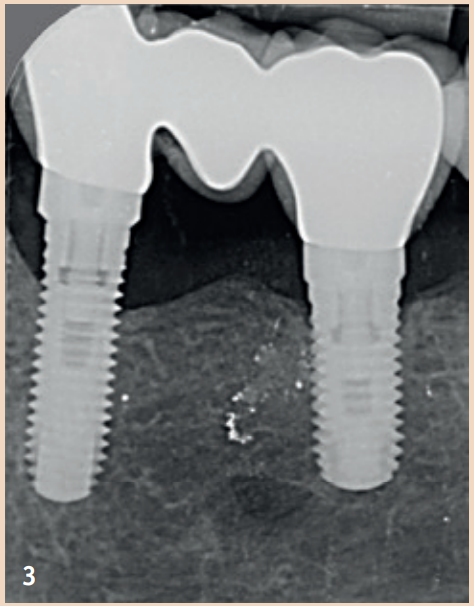

Generally recommended is the single tooth film, which is taken in right angle technique. To better assess the remodeling processes, it is recommended to take an X-ray image in addition to a probing finding at the time of the integration of the dental prosthesis (DP). The initial situation can thus be better compared with any resorption events that may occur during the course. Not every loss of bone around implants is equivalent to peri-implantitis. Rather, physiological remodeling processes after DP provision can also lead to bone loss. These are, compared to peri-implantitis, non-inflammatory and non-progressive.

Prevalence and Risk Factors

A systematic overview of the epidemiology of peri-implant health and diseases from 2015 dealt with post-implant complications. The prevalence of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis ranged, depending on the case definitions used, from 19 to 65 percent and from one to 47 percent. In subsequent meta-analyses, the mean prevalence for peri-implant mucositis was estimated at 43 (CI: 32–54 percent) and for peri-implantitis at 22 percent (CI: 14–30 percent).

General Risk Factors

Since peri-implantitis is attributed to bacterial "plaque," the ability of plaque to adhere to the implant surface is of great importance. It has been demonstrated that less biofilm adheres to smooth implant surfaces. Furthermore, preclinical studies have shown that bone loss in implants with polished surfaces was significantly lower compared to rough surfaces.

Smoking is considered a major influencing risk factor for the development of peri-implantitis.

Whether the absence or presence of attached/keratinized gingiva plays a role as another risk factor for the development of peri-implant diseases is scientifically controversial. There is a study that found no significant association between attached gingiva and peri-implantitis. In another study, however, an increased risk for both mucositis and peri-implantitis was demonstrated in the presence of attached/keratinized gingiva. The type of prosthetic implant restorations, whether fixed or removable, and the so-called prosthetic misfit or "faulty superstructure" could also have an influence on peri-implant diseases. There are currently no scientific results available for both factors. Additionally, the ability to maintain hygiene is being discussed. Serino and Ström (2009) found that implants with non-cleanable superstructures were more frequently affected by peri-implantitis.

Furthermore, a positive correlation between "implant age" and peri-implantitis prevalence was described in the systematic review by Derks and Tomasi (2015).

Periodontitis as a Risk Factor

A multitude of studies include periodontal health status in their assessments, allowing for possible associations between peri-implant diseases and periodontitis to be identified.

Marrone et al. 2013 showed that patients with active periodontitis are susceptible to the occurrence of peri-implantitis.

In the studies by Koldsland et al. 2011 and Ferreira et al. 2006, a positive correlation between the presence of periodontal disease and peri-implantitis was also found.

Patients with periodontal diseases show a statistically significant higher risk for peri-implant diseases.

In a cross-sectional study by Mir-Mari et al. from 2012, the prevalence of peri-implant diseases in a patient group integrated into a periodontal maintenance program was investigated. All subjects came from the same private practice, and the maintenance program included continuous re-evaluations every three to six months.

After completing the examinations, it was shown that the prevalence of peri-implantitis in patients of a private practice, with periodontal follow-up treatment, is between 12 and 22 percent. Nearly 40 percent had peri-implant mucositis. These prevalence values are comparable to results obtained from university clinic patients.

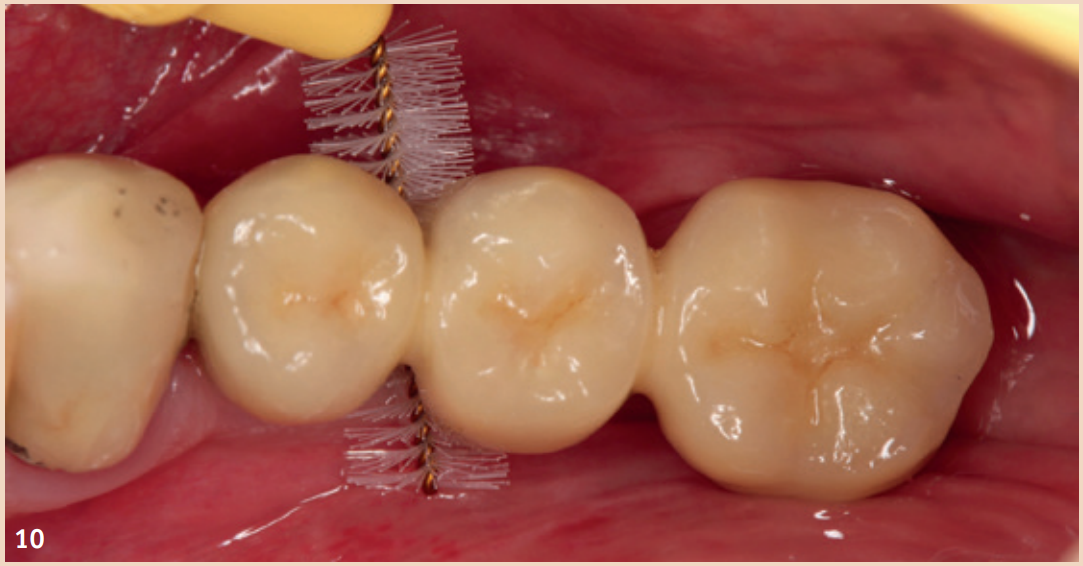

Therapy

Even though the therapy for peri-implant mucositis does not lead to complete healing in all cases, it is better and more cost-effective for the patient, but should be monitored at short intervals of three months. The recommended therapy is limited to regular, systematic, and professionally conducted plaque removal and improving home oral hygiene. Additional aids such as rinses, ointments with various ingredients, antibiotics, or lasers have no additional benefit in the treatment of peri-implant mucositis. Smoking should be stopped if possible, and the dental prosthesis should be checked for proper fit and corrected if necessary. The therapy for peri-implantitis is divided into (1) non-surgical therapy and (2) surgical therapy.

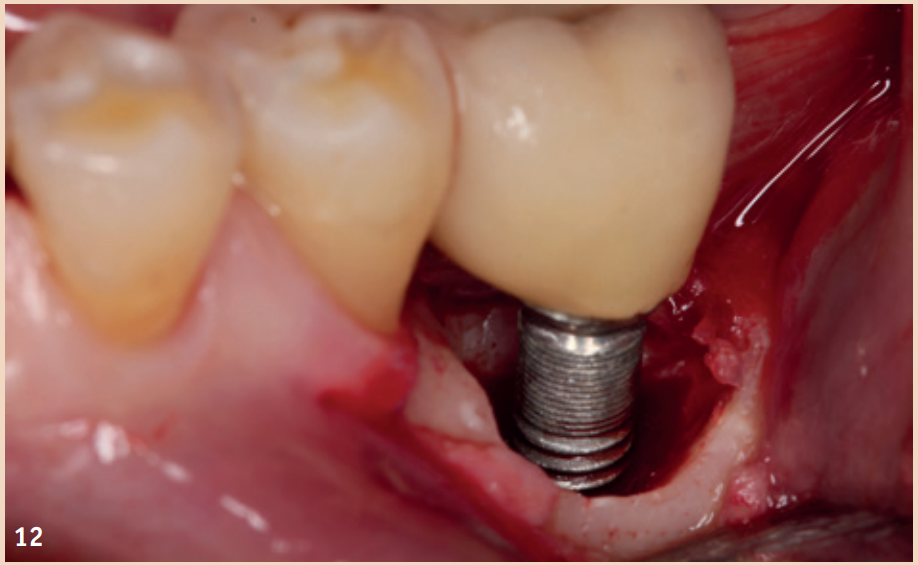

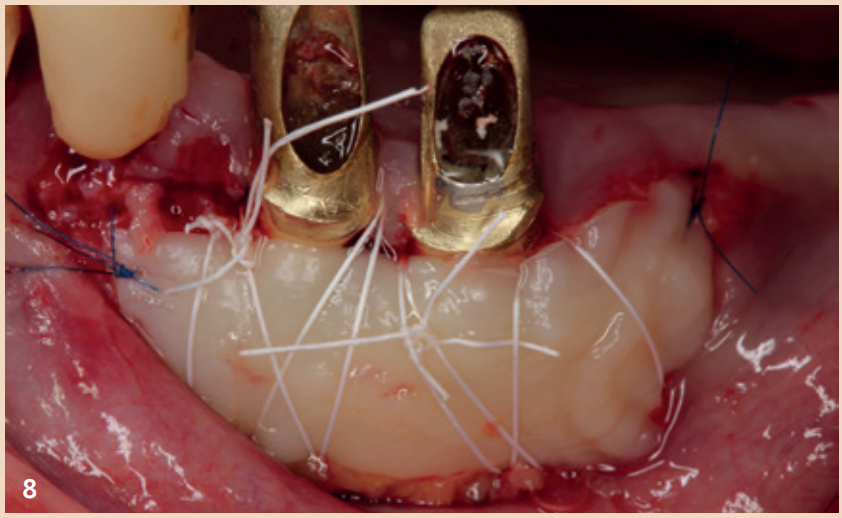

While adjunctive measures provided no additional benefit in peri-implant mucositis, they should be applied for the non-surgical therapy of peri-implantitis. In addition to the recommendation of powder-water jet devices with glycine powder, the Er:YAG laser also shows advantages regarding treatment success. Local antibiotics (doxycycline) and CHX chips can also be recommended as adjuncts. Even in the presence of peri-implantitis, the reduction of risk factors (inappropriate dental prosthesis, smoking) should not be overlooked. If there is already bone destruction of more than 7 mm, stopping the progression (stable result for more than six months) through purely non-surgical therapy is unlikely. In these cases, early surgical therapy should be preferred. None of the examined surgical therapy approaches showed an advantage in direct comparison. There is consensus only that the granulation tissue should be completely removed and that cleaning the implant surface plays a central role.

The defects that occur after cleaning can be filled with bone replacement material. Recessions are still very likely.

Outlook

Research in recent years clearly shows how differently the topic of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis is defined and observed. However, it cannot be said that there is an uncontrollable wave of peri-implantitis, and fortunately, the concerns of recent years have not been confirmed. To provide more clarity for practitioners and to give them better protocols for the treatment of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis, there is still a great need for research. Additionally, understanding regarding implants and the surrounding inflammation must increase. Implantation is promoted as a simple and safe method to quickly provide edentulous jaw areas with fixed teeth. This is indeed the case, but the conditions must be right to minimize subsequent interventions. Compared to other treatment methods, implants are still a relatively young field in dentistry. Changes in materials, surface characteristics, the type of implant (single-piece, multi-piece), the abutment connection, whether the prosthesis is cemented or screwed, the prosthesis itself, the patient (smoker, diabetes, oral hygiene, etc.), and last but not least, the practitioner all influence the likelihood of peri-implantitis. We will have to wait and see whether newer ceramic implants or the treatment of peri-implant inflammation with probiotics will lead to a reduction in risk. It remains exciting.

Conclusion

Peri-implant mucositis is defined as inflammation without bone loss/reduced bone level. The present inflammation affects the mucosa adjacent to the implant, whereas in the case of peri-implantitis, the inflammation is combined with bone loss. The etiological factor is referred to as "plaque." Similar to gingivitis, which represents inflammation of the marginal oral mucosa, plaque leads to mucositis. It is believed that some, but not all, mucosal changes progress to peri-implantitis.

Diagnosis is performed using a periodontal probe and an X-ray. Regular monitoring of peri-implant probing depths after the healing phase is recommended. The pressure should not exceed 0.25 N. Furthermore, Bleeding on Probing (BOP) should be assessed.

The prevalence of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis reaches values in studies, depending on the case definitions used, ranging from 19 to 65 percent and one to 47 percent. In subsequent meta-analyses, the mean prevalence for peri-implant mucositis was estimated at 43 percent and for peri-implantitis at 22 percent.

It has been demonstrated that less biofilm adheres to smooth implant surfaces. A systematic literature review has shown a clear correlation between smoking and peri-implant complications. Whether the absence of attached/keratinized gingiva is a possible risk factor for the development of peri-implant diseases is scientifically controversially discussed. There are both studies that found no correlation between periodontitis and peri-implantitis, as well as studies that show a significant association between both diseases. It is recommended to inform patients with periodontitis about the possible increased risk of developing peri-implantitis.

The early detection and subsequent treatment of peri-implant mucositis is the primary goal in the prevention of peri-implantitis. The recommended treatment for peri-implant mucositis is limited to regular, systematic, and professionally performed plaque removal and improving home oral hygiene. While adjunctive measures provided no additional benefit for peri-implant mucositis, they should be applied for the non-surgical treatment of peri-implantitis. In addition to the recommendation of powder-water jet devices with glycine powder, the Er:YAG laser or local antibiotics (doxycycline) and CHX chips also show advantages regarding treatment success. If there is already bone destruction of more than seven millimeters, stopping the progression (stable result for more than six months) through purely non-surgical therapy is unlikely. In these cases, early surgical therapy should be preferred. Regardless of the various surgical methods, there is consensus that the granulation tissue should be completely removed and that cleaning the implant surface plays a central role.

There is still a great need for research in the future to continuously reduce the prevalence rates of peri-implantitis, to identify the negative impact of risk factors on peri-implant health, and to develop new therapeutic approaches for the treatment of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis.