Mandibular Laterodeviations, Functional and Skeletal. Their Resolution through Functional Orthopedics

Machine translation

Original article is written in ES language (link to read it) .

Within the universe of dysgnathias, lateral deviations are not precisely the easiest to resolve. However, like the general laws, when addressed during growth ages, their resolution is certain and stable.

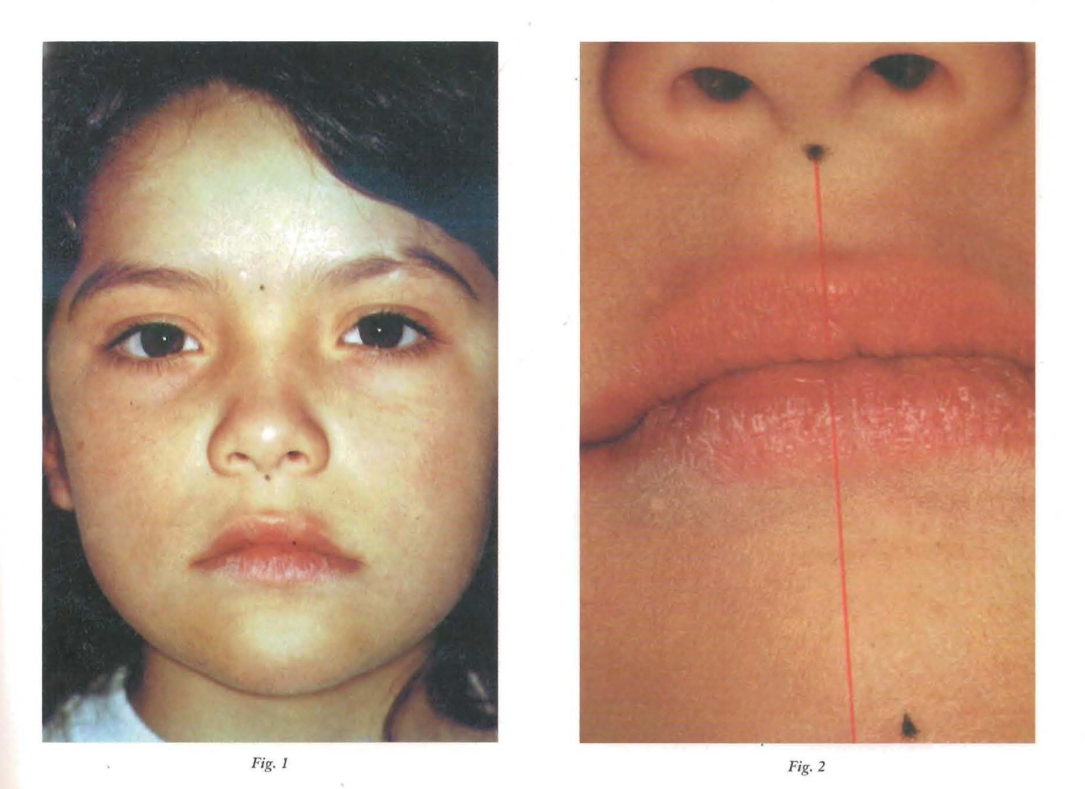

Framed within the alterations in the transverse direction, like so many other dysgnathias, this one has a pathognomonic facial sign: the deviation of the midline. (Photos 1 and 2).

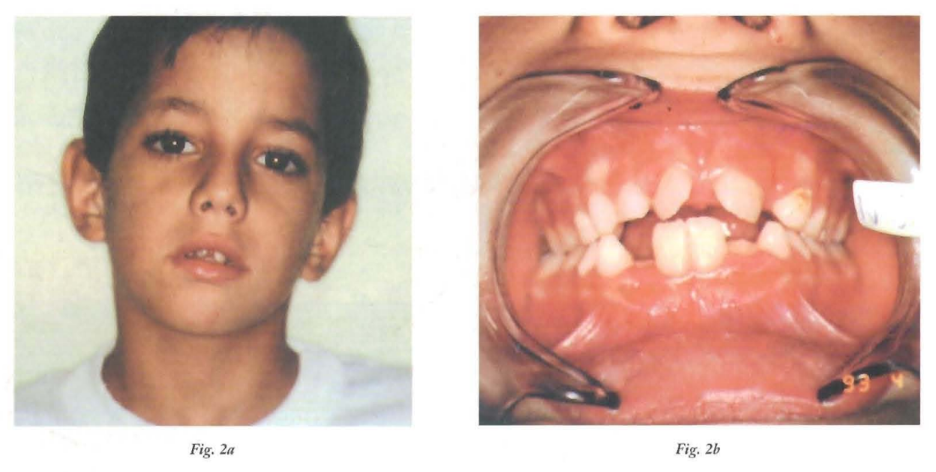

The altered cephalic position, with a tilt towards the opposite side of the mandibular deviation, is immediately a point of attention in our first encounter with the patient. (Photos 2a and 2b).

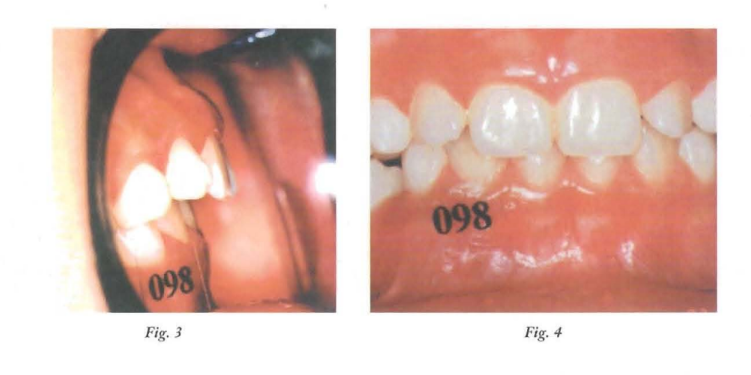

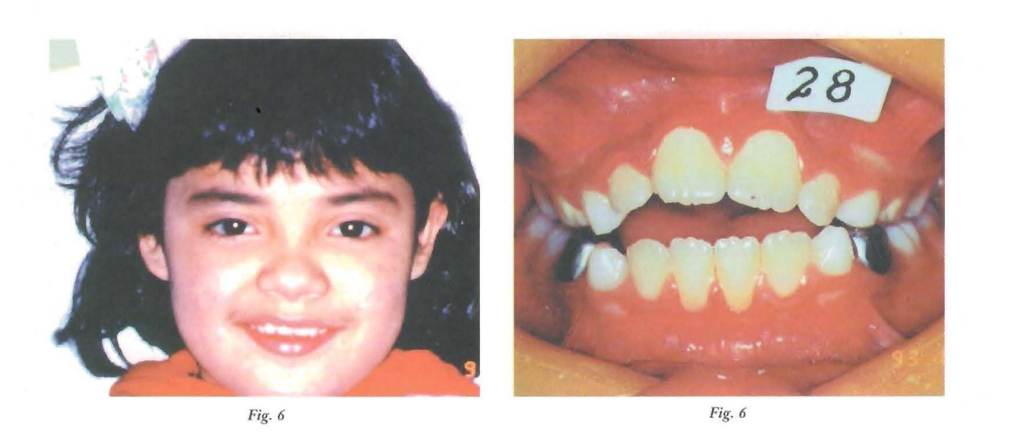

Addressing the dental arches, we observe the misalignment of the midlines. We must say that lateral deviations are a disorder associated with various dysgnathias. Indeed, we will find it associated with different alterations in the vertical sense: deep and open bites (Photos 3, 4, 5, and 6).

As well as in some mesial relationships and distorrelations (Photos 7, 7bis, 8, and 9).

The mismatch of the midline (having always ruled out a shift of the dental midline) is a common sign in two distinct types of lateral deviations: functional and skeletal. Understanding that the former are secondary signs to other pathologies, and that they resolve along the treatment of the primary ones, while the latter are shape alterations that have already been manifested in the bony architecture of the mandible.

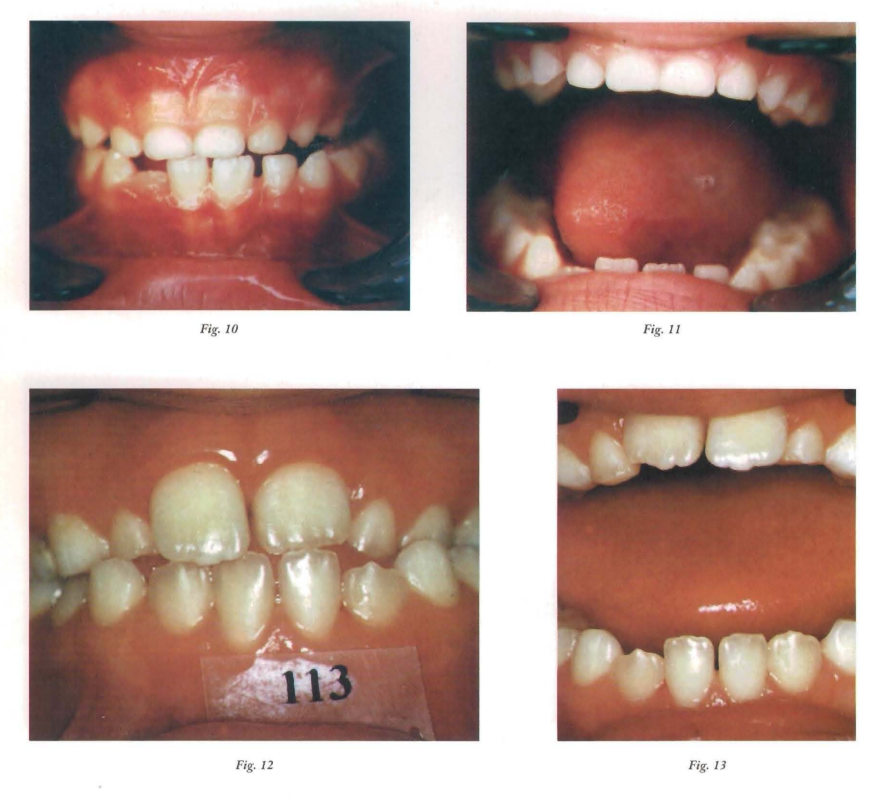

The differential diagnosis is performed with a clinical maneuver: maximum opening. In functional lateral deviations, we start from a centric occlusion with no coincidence of the dental midline; however, in maximum opening, the mandible returns to its centered position. In skeletal cases, during maximum opening, the deviation is maintained or exacerbated (photos 10, 11, 12, and 13).

Differential diagnosis of lateral deviations:

- Functional: in central opening.

- Skeletal: in opening it maintains or exacerbates the deviation.

Functional Lateral Deviations

What do we understand by functional lateral deviation? Well, it is one that does not yet affect the maxillomandibular bone structure, which is merely a position of comfort that the jaw adopts when encountering some obstacle in the closing path. Of course, if this problem occurs during growth periods and is not resolved, it ultimately manifests at the level of the bone architecture (skeletal lateral deviation).

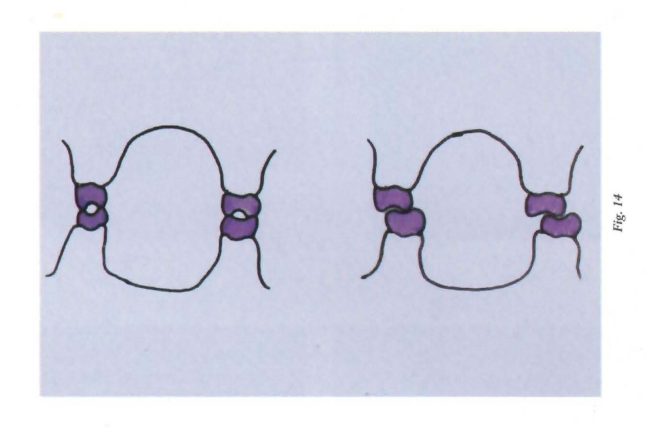

And what is the obstacle that the jaw encounters in its closing trajectory? A premature contact. In reality, the real obstacle is a discrepancy in the maxillomandibular transverse diameters, often due to a decrease in upper transverse diameters and sometimes also due to an increase in lower transverse diameters. Thus, this discrepancy is expressed in a cusp-to-cusp transverse relationship, which, being physiologically unfavorable, the patient corrects by laterally shifting the jaw until achieving a cusp-to-fossa relationship. (Photo 14)

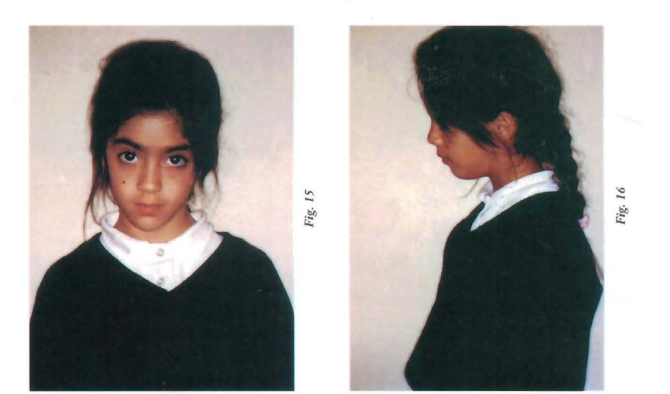

Let’s now look at the case of Noelia, who comes to the consultation at the age of 6. The first thing that catches our attention is the significant alteration in her posture! Whether we observe her from the front, where the presence of a scoliotic posture is noticeable, or from the side, there is an exaggeration of the physiological curves of the spine, with the classic "defeated child" posture that is often seen in mouth breathers. Likewise, at rest, Noelia's head remains tilted (Photos 15 and 16).

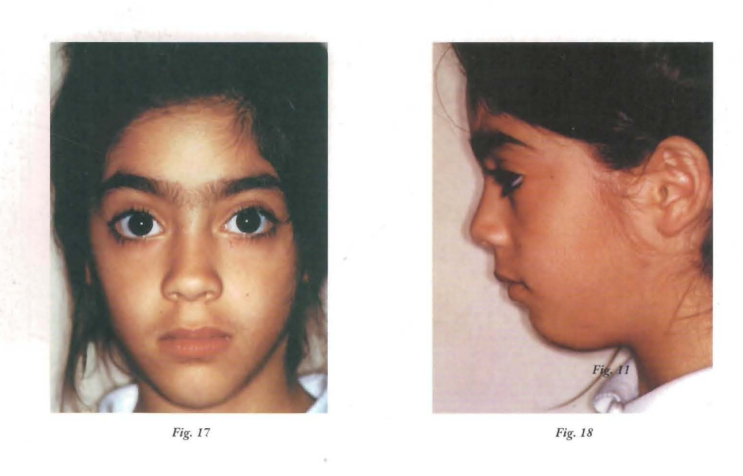

When observing the face from the front, the deviation of the facial midline to the right is evident (Photo 17 and 18).

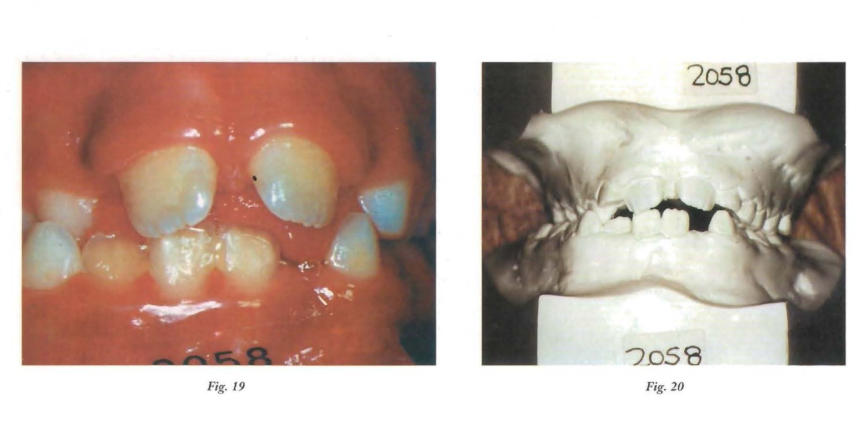

And we must also note the smallness of the nostrils and the contraction of the mentalis muscles, which together with the labial characteristics (shape, volume, tonicity, and texture of the hemimucosa), lead us to think of an anterior oral incompetence. The marked labiomental groove, as well as the underdeveloped cheekbones, complete the picture. The profile is slightly convex, the lips are everted, and the tongue bulges in the floor of the mouth, making us think of a low and backward postural attitude (Photos 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24).

When observing the mouth, we can say that the bases are regular, that there is a right posterior crossbite and a loss of dental midline, due to the deviated position of the jaw. On the other hand, the tongue is clearly seeking the inner surface of the lip to achieve anterior oral sealing. This labiolingual contact leaves its mark on the flattening of the anteroinferior alveolar ridge, and on the protrusion of the upper incisors.

Good. We are facing a lateral deviation. We then perform the clinical maneuver that allows us to make the differential diagnosis and we conclude that we are, happily, facing a functional problem! And we are facing a functional problem, not only because it is a functional lateral deviation, but also because the etiopathogenesis is functional. So, what happened here? There is mouth breathing, there is a low tongue posture, there is a lack of stimulus for the transverse development of the palate; there is a posterior transverse relationship cusp to cusp; there is a mandibular deviation to achieve a mandibular relationship cusp to fossa (Photos 25 and 26).

Upon observing the telerradiography, we find hypertrophy of the adenoids, lack of linguoalveolar contact (absence of posterior oral sealing), flattening of the soft chin (hyperactivity of the compensatory muscles of the chin), and a hyoid located further back than it should be (tongue back). From the cephalometric study conducted with the Schwartz cephalogram, we will mention an increased interbasal angle and a slight decrease in the size of the upper jaw.

Diagnosis of functional lateral deviation of the mandible with decreased upper transverse diameters, right posterior crossbite, mouth breathing, atypical swallowing, and low and back tongue posture.

Our therapeutic objectives in this case are: first, to recover the upper transverse diameters and desensitize the afferents of the maxillomandibular relationships. In a second stage, to reorganize the maxillomandibular relationships, together with functional and postural rehabilitation.

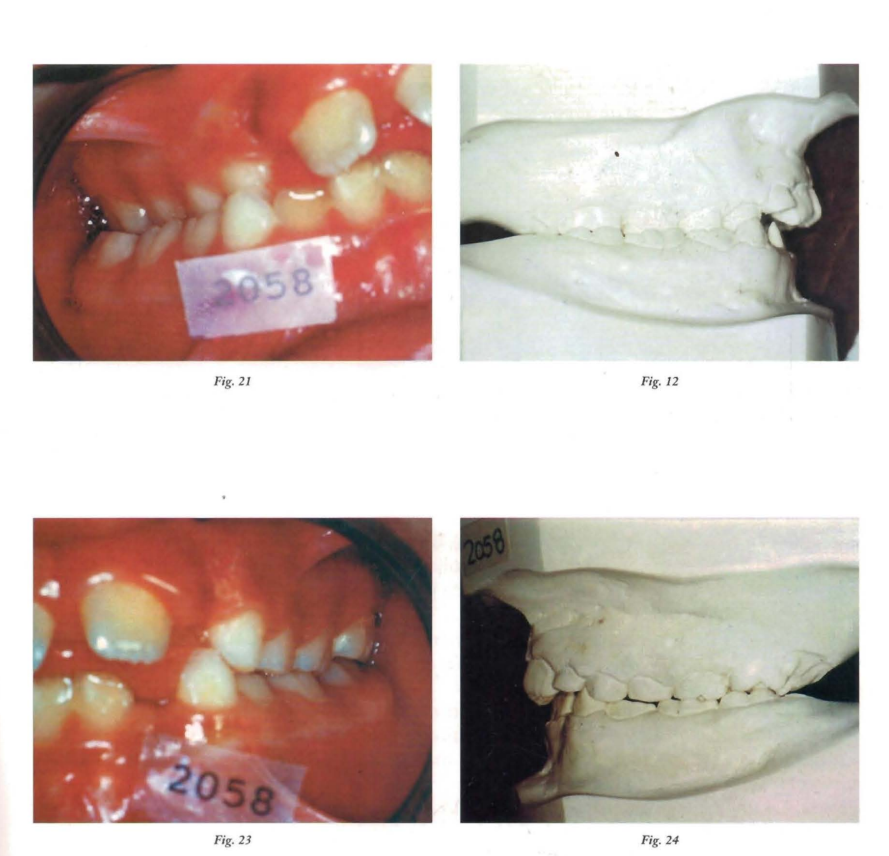

We decided to carry out the first stage with a plate with chewing pads, with a usage indication of 24 hrs. x 24 hrs. and activating 1/4 turn first every 7 days and then every 4 days. (Photo 27).

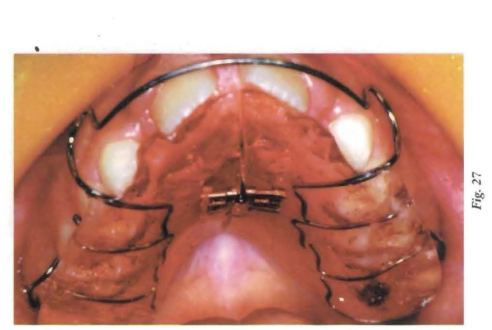

At six months, having achieved the therapeutic objectives of the first stage, we reevaluated (Photos 28, 29, 30, 31, and 32).

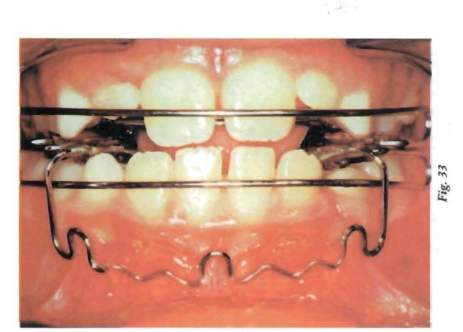

We then move on to the second stage in which we use an Open Elastic Activator from Klammt with lower retrolabial shields (Photo 33).

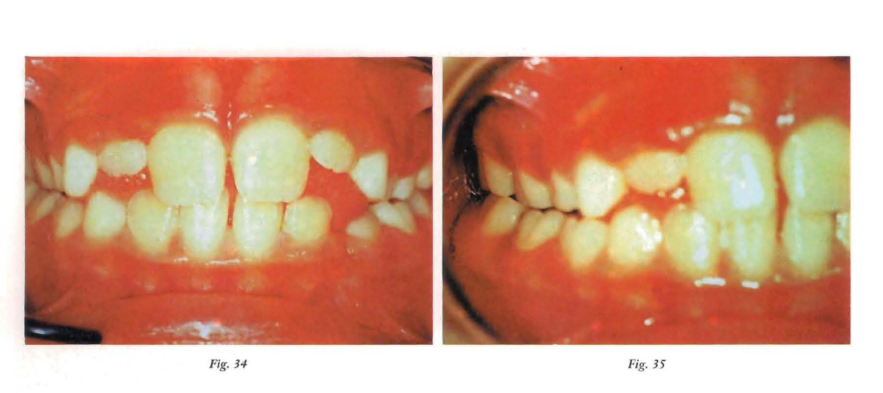

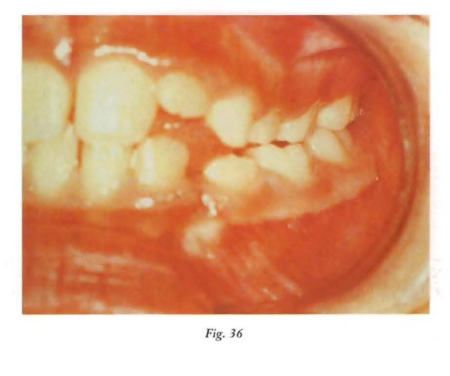

Six months later, the interincisal relationship and the transverse diameters have been ordered, as well as substantially improving the initial dysfunctions, although the habit in the abnormal cephalic posture persists (Photos 34, 35, and 36).

Skeletal laterodeviations

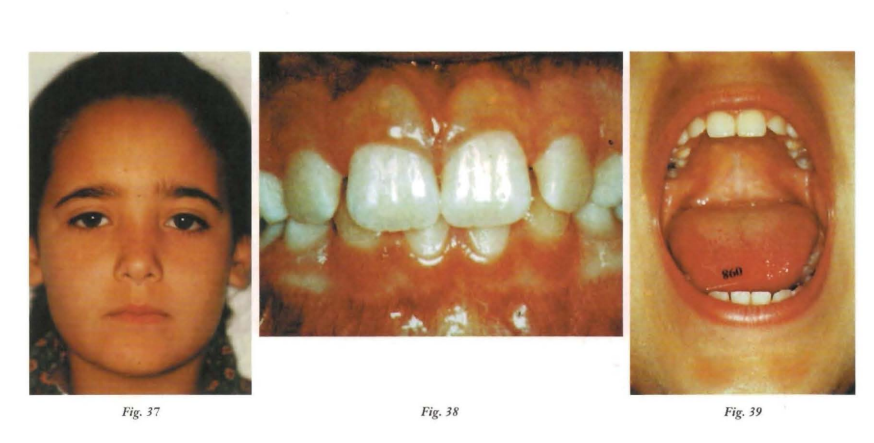

As we have already mentioned, these are those that occur due to alterations in the bone architecture and that we clinically distinguish by the altered facial midline and the permanence of the laterodeviation in occlusion and in maximum opening. (Photos 37, 38, and 39)

If we refer to the etiology, we must say that these alterations occur due to genetic disorders, in the case of ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint, when the patient has suffered a condylar fracture, or due to recurrent middle ear infections. We will analyze this pathology in light of two clinical cases:

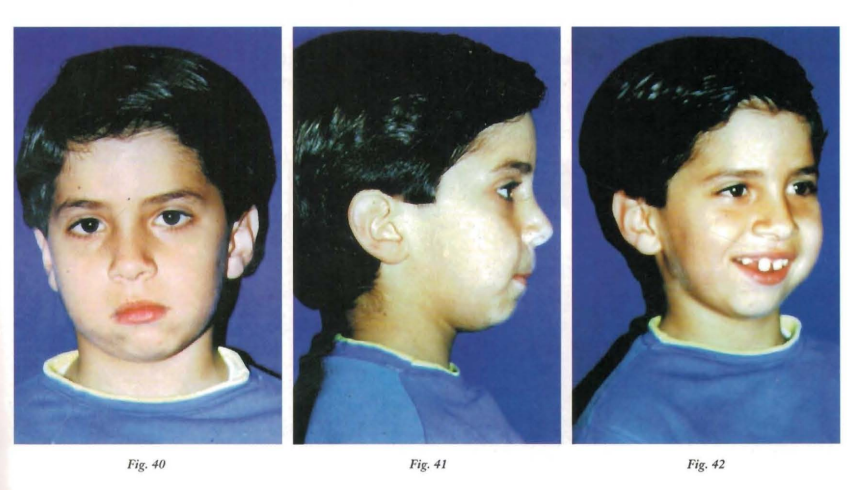

The child G. M. is brought to the consultation at the age of five by his mother, who notices "the twisted face." From the anamnesis, it is revealed that at the age of two there was a trauma with a clavicular fracture and a temporary upper canine fracture (Photos 40, 41, and 42).

Observed from the front, the deviation of the facial midline to the right is evident, a deviation that increases with maximum opening. The profile is convex with a noticeable delay of the soft Pg point.

G. M. is a mixed breather, with atypical swallowing and has the habit of sucking on the lower lip (Photos 43, 44, and 45).

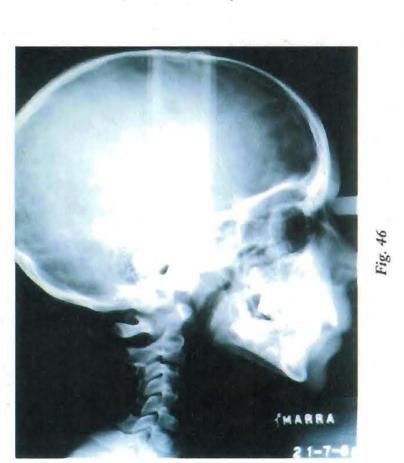

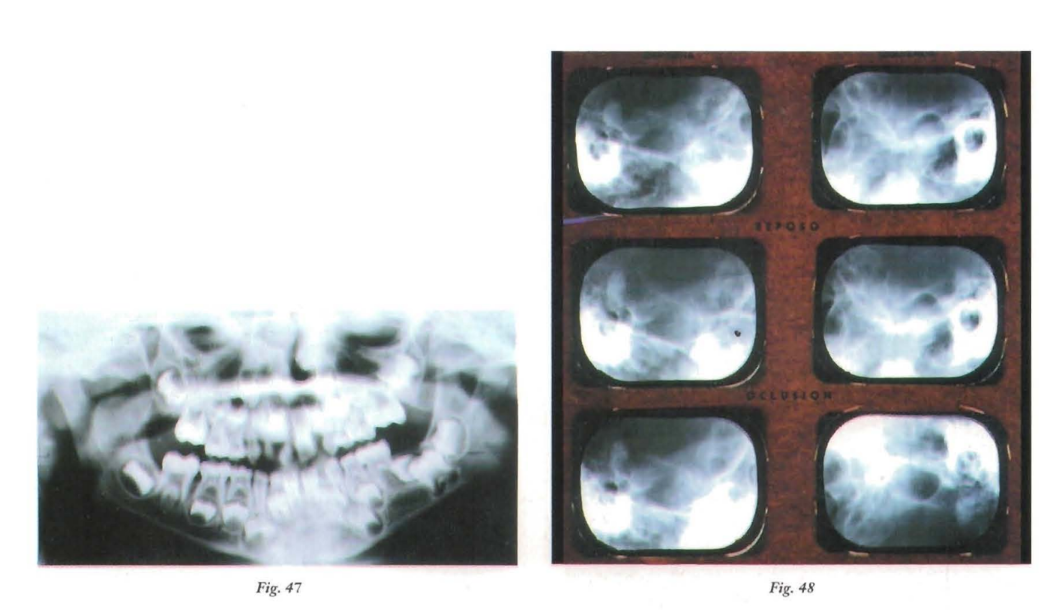

The dental arches, at a stage of replacement more evolved than chronological age, also show us the loss of the dental midline, repeating the deviation to the right, as well as the loss of the interincisal relationship due to the flattening of the anteroinferior alveolar ridge produced by labiolingual dysfunction. (Photos 46, 47, and 48)

The radiographic study gives us the answer: already in the panoramic view, the absence of the right condyle is observed, which is then confirmed with condylography. The telerradiographic analysis also shows a significant decrease in mandibular size along with a retroposition of the lower jaw (disto-relation).

That is to say, we are facing a structural lateral mandibular deviation with mandibular micrognathia, suggesting that the etiology would be traumatic, with associated swallowing alterations.

In growth ages, the difference in contraction strength between the elevating and depressing muscles of the jaw, as well as the increase in resting tone in the muscles adjacent to the traumatized area, can deform the mandibular body; therefore, it is essential to balance as soon as possible the mechanisms that govern the neuromuscular masticatory function.

It is necessary, and with the utmost urgency, to restore the free joint play, as well as to maximize propulsion and opening, seeking to avoid joint ankylosis, mandibular growth deformation, and decreased opening, all sequelae present if the appropriate treatment is not implemented.

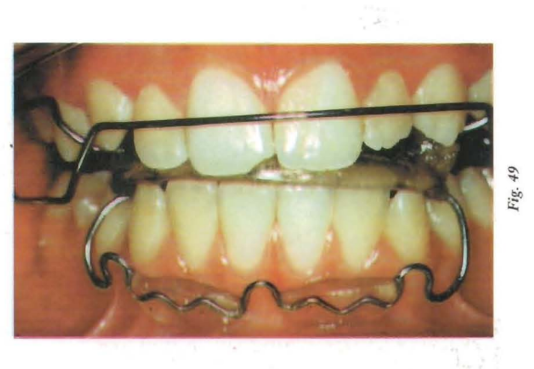

With the aforementioned as therapeutic objectives, a Bionator 11 with lower retrolabial shields is installed, aided by functional rehabilitation (Photo 49).

The device installed in the mouth, with an indication for almost permanent use, forces the centered functioning of the jaw, causing a neuromuscular adaptation.

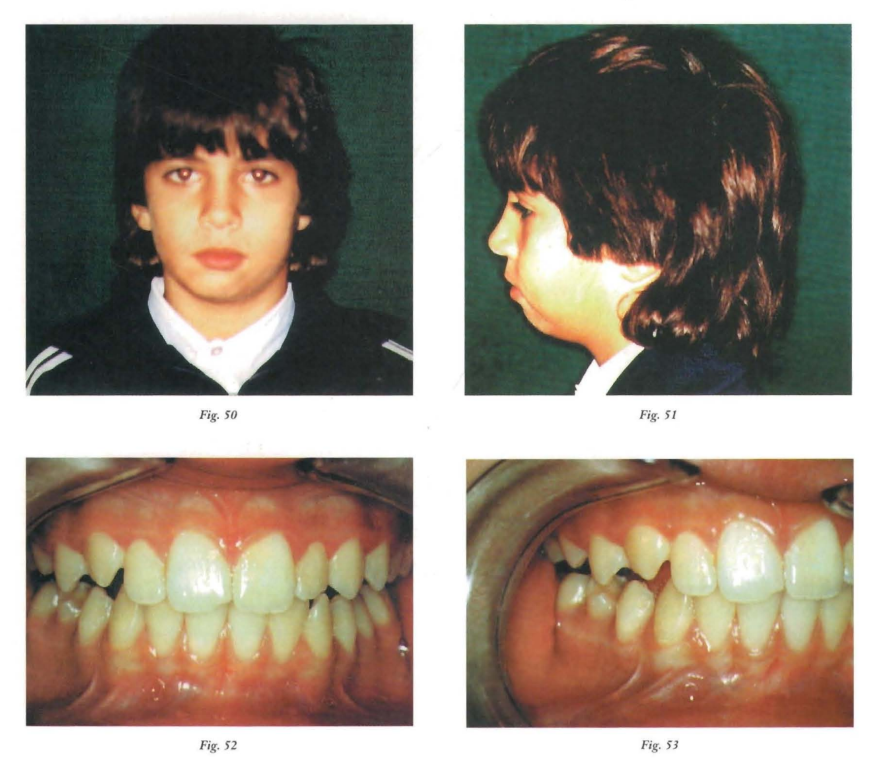

Once the replacement of the posterior sectors began, with the eruption guide of the bimaxillary functional appliance, a correct intra-arch engagement was formed, so that now, from the neuromuscular readaptation, the periodontal proprioceptive memory is achieved, which also aids in the correct mandibular position (Photos 50, 51, 52, 53, and 54).

Anita presents herself at the consultation during the course taking place at the Central Hospital "Dr. Castro Rendon" in the city of Neuquén, at 9 years and seven months old, referred by a colleague who had detected the presence of facial asymmetry.

The main background is a car accident as a result of which the right condyle was removed (fortunately, the MRI that was performed at that time was recovered).

At the time of the consultation, the general condition of the patient is normal, although a slight vertebral lordosis is detected.

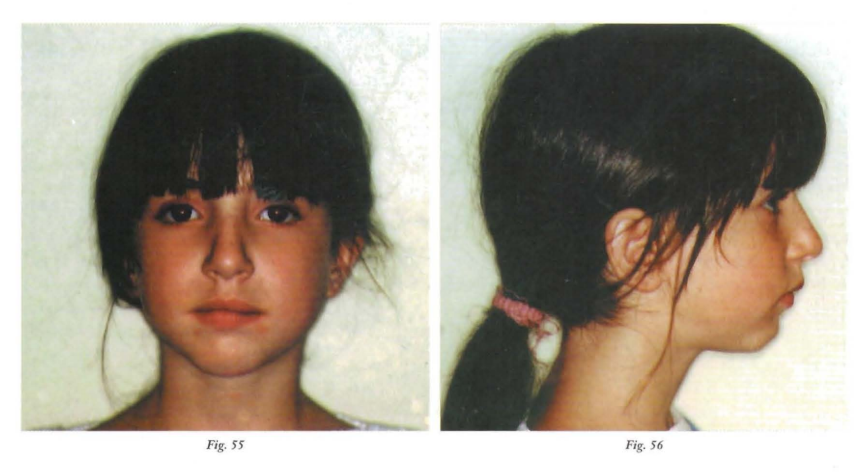

In the facial examination, we recognize right mandibular asymmetry, a short upper lip, and an everted lower lip. The labiomental groove is marked and the profile is convex, (Photos 55 and 56)

From a functional point of view, the patient is a mouth breather, as a consequence of which she maintains a low tongue posture with a short and hypotonic upper lip, a hypoactive lower lip, presenting anterior oral incompetence and a hyperactive chin.

When conducting the study of the A.T.M., we reach the most interesting part of the case, as it is the reason for the initial consultation and where our curiosity is most stimulated.

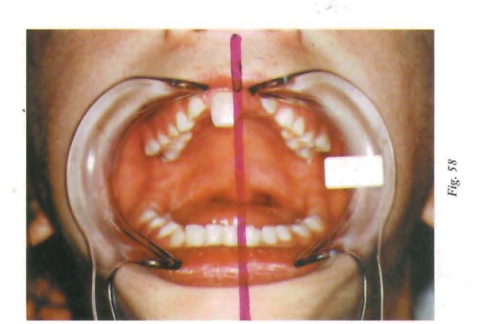

The most notable elements are: a significant limitation in opening (which does not exceed 30 mm) and a strong deviation to the right during maximum opening caused by the absence of the condyle (Photo 58).

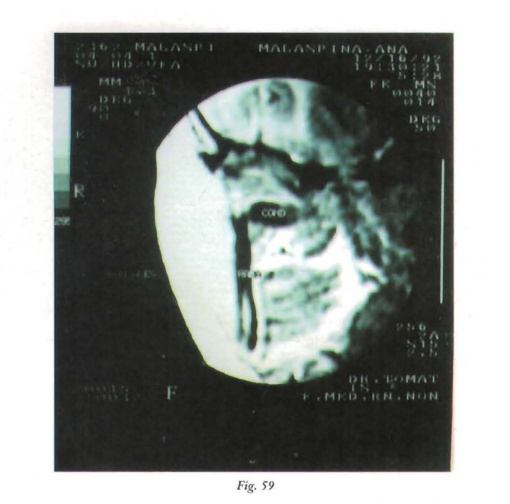

The study of the A.T.M. was completed with the information provided by the MRI performed at the time of the accident. It clearly shows that due to the trauma sustained during the accident, the condyle is positioned at almost 90 degrees from its neck, and the report stated verbatim "fracture of the right condyle, with displacement of the free fragment inward, forward, and downward. The articular meniscus appears to accompany the condylar fragment; the glenoid cavity has a normal morphology, with no structures inside it. This study was what decided the condilectomy (Photo 59).

We then proceeded to analyze the patient's mouth and observed that the apical base is regular; that the dental arches have their transverse diameters decreased, both the upper and lower, with the greatest discrepancy in the 6/6 diameters.

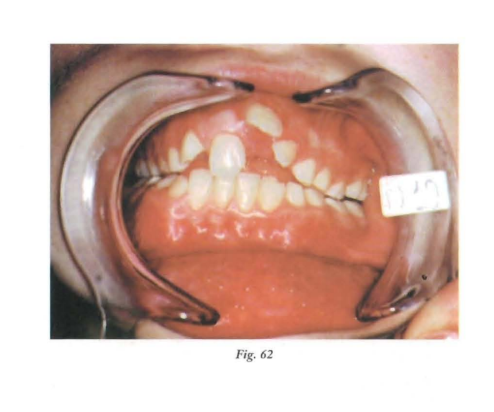

In the sagittal direction, the overjet is slightly increased. The molar key is of normal occlusion and the canine is of slight distocclusion. In the vertical direction, in some dental pieces, the crossbite is increased and in others it does not reach the measurements taken as normal (Photos 60, 61, and 62).

The incisal sum is 30 mm, and based on the bicigomatic diameter, it is considered that the dental size is normodontic, as the ca.EI. (individual facial bone coefficient) is 0.99. There is a significant dental dystopia with transposition between the upper lateral and canine on the left side.

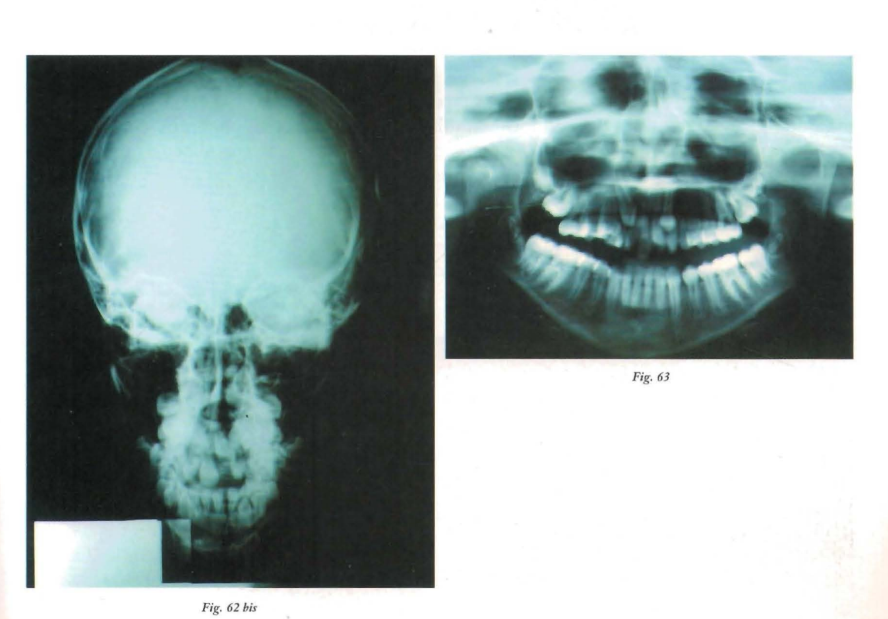

The cephalometric radiography highlights the presence of adenoids at the level of the lower third of the pterygomaxillary fossa, generating significant difficulty in the airway passage. We also confirm the low postural attitude of the tongue, already observed clinically. (Photos 62 bis, 63, and 64).

When performing cephalometric measurements, a noteworthy data point is the divergence of bases, with involvement of the lower jaw, mandibular distortion, and a slight increase in the size of the upper jaw.

Once the study of the patient, which we have summarized as much as possible for space reasons, is completed, the diagnosis is made, which as we all know is fundamental for setting therapeutic objectives and the treatment plan. We must address the morphological, functional, and structural problems of the patient, and in this particular case, analyze the serious issue represented by the absence of the mandibular condyle. In summary, we can say that we are facing a structural mandibular laterodeviation, with absence of the right condyle, distortion with divergence of bases, dental dystopias, and associated functional problems.

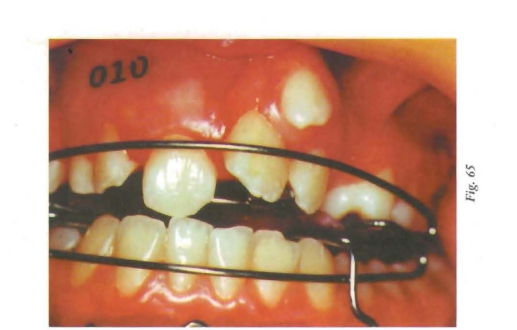

Anita was fitted at the beginning of the treatment with a Bionator II with lower retrolabial shields, and sixteen months later it was replaced with an Open Elastic Activator by Klamm with lower retrolabial shields (Photo 65).

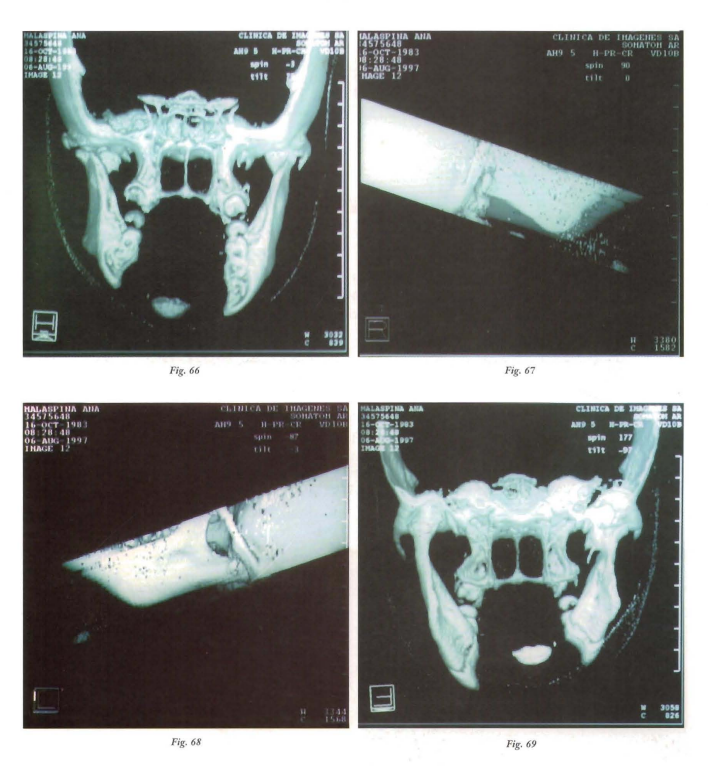

The main objective of the treatment was to rehabilitate mandibular movement, guiding the centric and generating a readaptation of soft tissues at the level of the injured T.M.J. Subsequent studies with computed tomography confirmed the formation of adaptive tissue in the condylar area, which led to normal mandibular kinetics, leaving the histology of the same as a question, a study that surpassed our possibilities as clinicians (Photos 66, 67, 68, and 69).

Once the clinical case has been analyzed, it is interesting to highlight some elements that we consider important. First of all, we must say that according to the collected bibliography and our experience, when a trauma of this nature occurs, every effort should be made to preserve the remaining condyle, as once repositioned in an adequate position, it serves as a matrix to regenerate the tissue.

Analyzing another aspect, we must say that when we focused on assembling the dental arches, the transposition between the left lateral and the canine and the location of the canine root forced us to place a tie apparatus. But it is important to highlight that the nocturnal use of the A.A.E.K. continued (Photo 70).

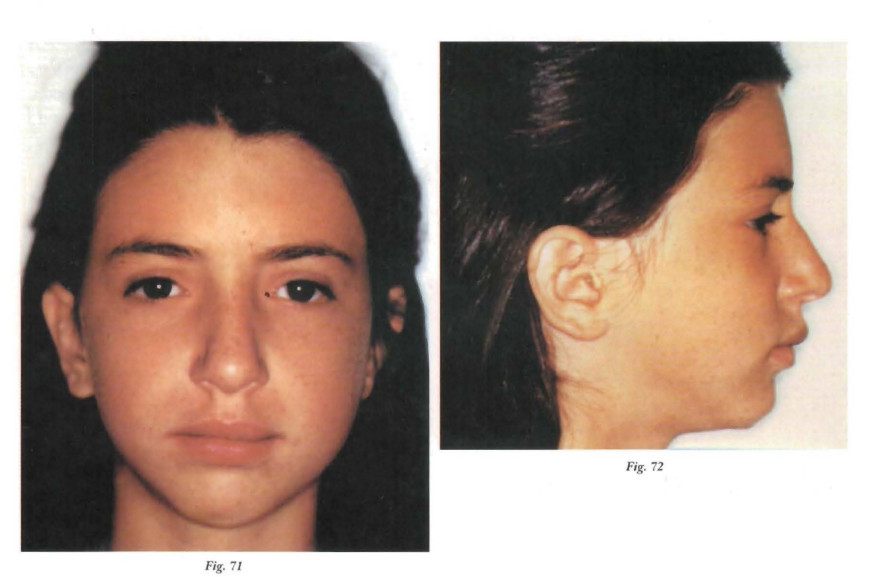

Through the implemented treatment, the growth of the right hemimandible was recovered almost to compensate for the asymmetry, and during the opening movement, from occlusion to maximum opening, no mandibular deviation is observed (Photos 71, 72, 73, 74, and 75).

This produced in us a new functional orthopedic experience, given that our concepts were always managed with moderately normal structures and all their components. In the face of this clinical case, and despite the gathered bibliography, we did not have a concrete and certain backing for our work, but we relied on our functional convictions and the results obtained support these general concepts that govern our treatments.

This is a case where, with functional orthopedics, and therefore from function, we have rehabilitated a system where an important element was missing; the condyle of the A.T.M. Through the rearrangement of the periarticular soft tissues and generating a centric engram, the function was reordered based on the remaining components.

Conclusions

Two different nosological entities are presented, functional mandibular lateral deviations and structural ones, with the same pathognomonic sign: the deviation of the facial midline.

A clinical case is presented showing the simple way to resolve the first and then, through two cases with severe A.T.M. lesions, the possibilities that Functional Orthopedics offers to resolve through compensation mechanisms.

G. Lorenz, N. H. Rivas, A. Ceccarelli

Bibliography

- Maxillofacial Orthopedics/Clinical and Apparatus. Temporomandibular Joint. Volume III John W. Witzig, Terrance J. Spahl. 1993 Scientific and Technical Publishing S.A.

- Diseases of the temporomandibular apparatus A multidisciplinary approach. Douglas H; Morgall, D.D.S., William P. Hall, M.O., James Veinvas, D.D.S. and F.A.C.D. Ed. Mundi.

- Proprioceptive sensitivity and transverse anomalies of the closure pathway. A. Coutand and G. Demadre Maysson. Journal "Orthodontics" No 76 year XXXVIII, Nov. 74.

- Response to therapeutic functional stimulus in a child with growth deficiency caused by unilateral ankylosis. Prof Dr. Carlos Ricardo Guardo. Rev. "Orthodontics", year XLVII Vol 47 No 94 Nov. 83.

- Summary of the main characteristics of facial growth. Prof Dr. Jean Oelaire. Rev. of the A.A.O.F.M. No 64, year 81.

- Manual on facial growth. Enlow, O. Ed. Intermedica Bs. As. Arg. 1982.

- Neuromuscular physiology and functional orthopedics. Guardo C. et al. Rev. Circle Arg. of Dentistry, No 3142-1972.

- Clinical implications of A.T.M. Robert M. Rickets O.D.S., M.S. Rev. "Orthodontics" No 61, year XX XI April 67.

- Orthopedic treatment in condylar-mandibular trauma. Nilda B. Bacigalupo, Maria N. T. de Duffy, Alberto N. R. Meroni, Carlos E. Meroni and Liliana C. Spinedi. Rev. of the A.A.O.F.M. Vol 13 No 42 1978.