Jaw surgery for the treatment of sleep apnea syndrome

Machine translation

Original article is written in ES language (link to read it) .

Introduction

Maxillofacial surgeons perform bone surgery to correct skeletal and occlusal deformities of the jaws. Understanding the influence of skeletal movements on the soft tissues of the head and neck and their alterations in facial appearance has been the basis of orthognathic surgery. In recent years, the effects that maxillary advancement surgery has on the palate and the base of the tongue have been increasingly understood. In collaboration with pulmonologists and neurophysiologists, we pioneered the publication in 1991 of the relationship between sleep apnea syndrome and maxillofacial alterations and their solution with maxillomandibular advancements in the English literature.

Since then, there is demonstrated evidence that maxillomandibular advancement is highly effective in the multilevel treatment of OSA.

CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) is the gold standard for the treatment of OSAHS. The Cochrane review conducted in 2005 concluded that there is no evidence for the widespread use of surgery in patients with mild to moderate sleepiness associated with sleep apnea. Definitely, in patients with moderate to severe OSAS, who are unable to tolerate CPAP, surgery is the only alternative. The literature shows that 30-80% of patients do not use CPAP for a minimum of 4 hours per night and that 40-60% abandon it after 2 years. Considering that CPAP is a lifelong treatment, there is a growing interest in effective surgical solutions.

We believe there is a role in selected cases where a bony surgical procedure improves the airway at multiple levels (oro-hypopharynx).

Skeletal surgery

Maxillofacial surgeons with an interest in orthognathic surgery have experience in performing maxillary and mandibular osteotomies in the management of developmental or acquired anomalies of the facial skeleton and occlusion.

This surgery improves the appearance of the face and occlusion, which is the primary reason for seeking the size and relative position of the maxillae. It achieves facial harmonization, aesthetic improvement, and occlusal normalization.

Orthognathic surgery allows, through a combination of advancement-retrogression movements and vertical changes, to obtain aesthetic and functional results in a predictable and stable manner. This is carried out together with a preoperative orthodontic period that lasts between 12-14 months.

The postoperative result is a functional, stable occlusion and excellent aesthetics. The most common procedures are sagittal mandibular osteotomy, Le Fort I osteotomy, and genioplasty performed via the intraoral approach.

The Le Fort I osteotomy mobilizes the maxilla and the palate from the base of the skull at the level of the floor of the cranial fossa, expanding and advancing the airway. The sagittal osteotomy of the mandible, Obwegesser osteotomy, is performed with sagittal cuts, allowing the mandible to be moved forward with a large bone contact surface; the cuts begin at the lingual part of the ramus above the mandibular canal and end in the body of the mandible at the buccal part at the level of the first molar, the mandible is separated in half and the fragment with teeth is advanced with the maxilla and mandible in the position predetermined by splints in the desired occlusion.

Osteosynthesis is performed with plates and screws. The movements of the soft tissues can be predicted preoperatively based on the proposed bone movements using prediction software and are used to advise patients on changes in aesthetics and/or appearance. Orthognathic surgery is predominantly performed on patients with class II and III orthodontics to achieve class I with functional occlusion postoperatively. An occlusal, dental cephalometric study, and especially a facial analysis will be conducted as a basis.

Since the articles by Powel and Guilleminault and the one published by us, it is increasingly recognized that maxillary osteotomies have a positive or negative effect on the posterior airway at the level of the palate and/or tongue base. These changes are predictable and depend on the direction of the movement of the maxilla and mandible, which together with a genioplasty advancement significantly improves the posterior airway. In general, the magnitude of change must exceed 10-12 mm.

The posterior airway can be mediated in lateral cephalometric radiographs and more recently in CBCT studies. However, more important than the radiological findings is the resolution of the symptoms of OSAHS and the demonstrable improvement in polysomnographic studies. It has even been shown long ago that mandibular setback produces OSAHS in a previously healthy person, thus the value of bimaxillary advancement as a very effective multilevel treatment for severe OSAHS is increasingly diminished.

Maxillomandibular advancement

Patients offered orthognathic surgery must have moderate to severe OSAHS, confirmed by polysomnographic studies, and have failed other simpler treatments and lifestyle hygiene measures.

Airway obstruction is classified by Fujita into 3 levels. There are three areas of collapse in the airway:

- Type I: soft palate.

- Type II: base of the tongue and soft palate.

- Type III: at the base of the tongue.

Diagnosing the level of obstruction and collapse of the airway is difficult and includes techniques such as nasoendoscopy during sleep, CT of the upper airway, etc. Lateral cephalometric radiography and CBCT are useful for delineating the posterior airway. Mandibular advancement devices can be useful as predictors to define the level of obstruction at the base of the tongue. Our experience suggests that the more severe the OSAHS, the problem is multi-level, and the solution should be applied at both the oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal levels.

Criteria for maxillomandibular advancement

- Clear clinic of OSAHS Apnea-hypopnea index greater than 20

- Failure or abandonment of CPAP

- Obstruction at the base of the tongue or multilevel.

There is a clear misconception among professionals that only patients who would benefit from bimaxillary advancement or orthognathic surgery are those with a retruded mandible and class II malocclusion.

In patients with class I occlusion, we maintain the preoperative occlusion maximally advanced for both the maxilla and the mandible in such a way that a benefit and improvement in the airway at the level of the palate and base of the tongue is obtained.

It is interesting that one of the potential problems of bimaxillary advancement could be the change that accompanies the aesthetics of the face; however, in most cases, the effect has been seen as positive by our patients as it has a rejuvenating effect and results in faces that are more aesthetically harmonious according to current beauty standards.

Summary

In our series of 32 patients who were treated with bimaxillary advancement for moderate to severe OSA, the AIH index was 36.5, ranging from 25-74, reducing to a postoperative average of 8, ranging from 0 to 24, the average age was 41 years and the average BMI was 27.2.

The success rate was 92%. Two patients required preoperative tracheostomy which was removed after 4 days, they were extremely severe cases. One patient continues with CPAP despite the surgery. Bimaxillary advancement for the treatment of OSA is an effective multilevel procedure. Success rates exceed 85%. Patients require 3-4 days of hospitalization and 24 hours in ICU. The average time off work is 3 weeks considering this as a single procedure with a high percentage of cures for OSA. It is much cheaper than lifelong CPAP.

In line with the challenge of treating severe OSA in the most effective way, the European Respiratory Society has aimed to determine the value of other non-CPAP treatments. The conclusions regarding maxillomandibular advancement after reviewing the literature are that bimaxillary advancement is as effective as CPAP in patients who have failed or do not want conservative treatments, particularly young individuals, with no excessive BMI and/or other comorbidities.

This is our experience with a group of patients with severe OSA who are unable to tolerate CPAP and are exposed to all the associated risks and mortality of OSA. We believe that these patients have benefited extraordinarily and that similar patients accepting the risk of skeletal surgery is important.

Conclusions

Bimaxillary advancement surgery is useful in the treatment of moderate or severe sleep apnea syndrome. The percentage of healing and effectiveness is similar to CPAP and avoids prolonged lifelong treatment, and in the crisis era we live in, it is much cheaper than lifelong treatment with CPAP.

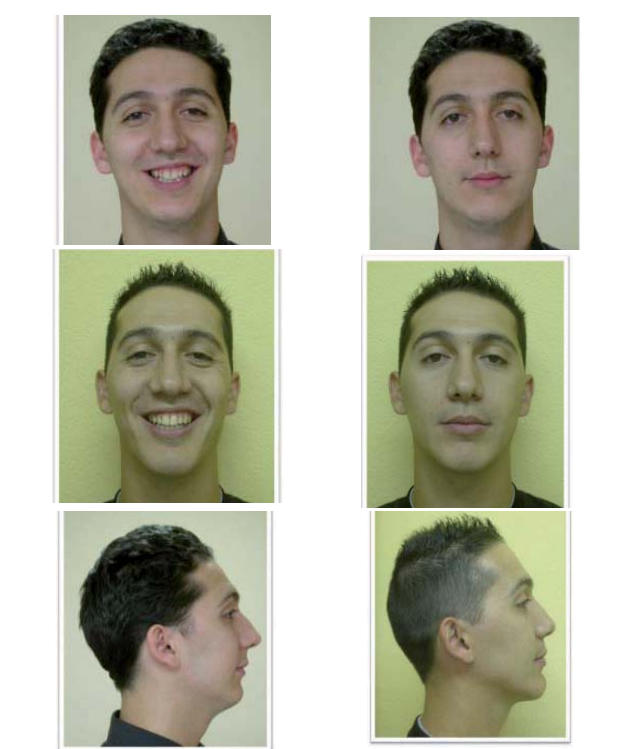

Clinical case No. 1

Orthodontist: Dr. Páez

The 23-year-old patient presented with severe sleep apnea syndrome. The patient came for consultation for palate and pharynx surgery. Evaluating his anthro-cephalometric characteristics, the patient was informed about the combination of bimaxillary advancement surgery and orthodontics. After a period of 10 months of preoperative orthodontics, the patient was operated on, undergoing a 14 mm mandibular advancement, 3 mm posterior descent, 14 mm mandibular advancement, and genioplasty. The patient evolved satisfactorily, with apneas and hypopneas disappearing.

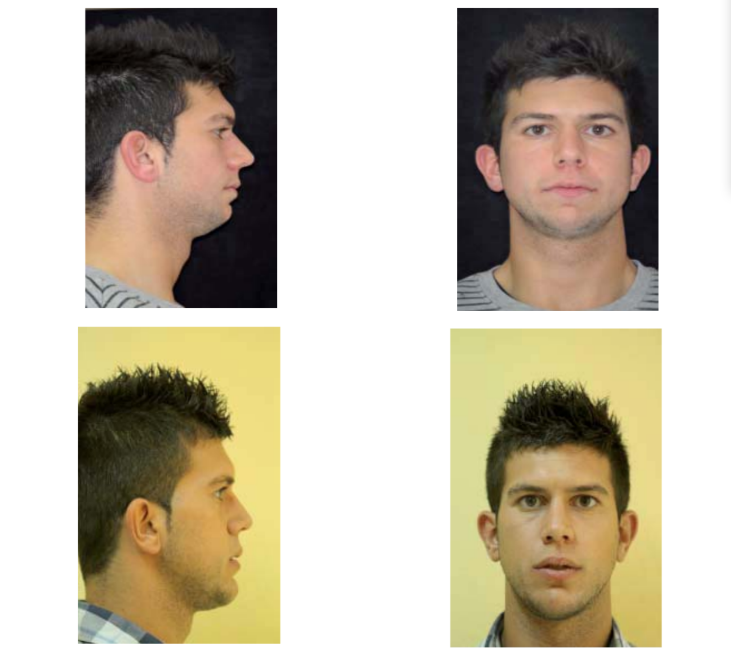

Clinical case No. 2

Orthodontist: Dr. Población.

Patient referred by the sleep unit of Ruber Internacional hospital. 22-year-old patient with severe sleep apnea syndrome and CPAP intolerance. The patient underwent surgical intervention with a maxillary advancement of 9 mm and a mandibular advancement of 12 mm, advancement genioplasty, and vertical augmentation. The polysomnographic parameters normalized. The cosmetic improvement after bimaxillary advancement surgery is evident.

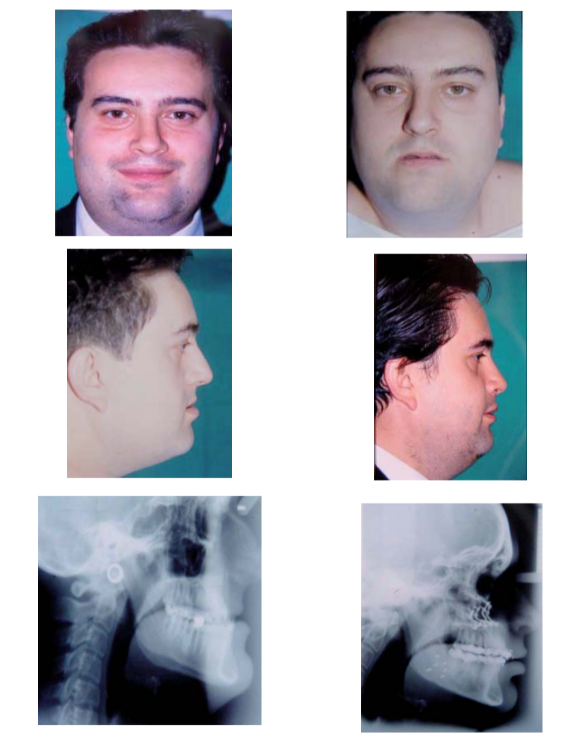

Clinical case no. 3

Orthodontist: Dr. Berraquero.

Patient with morbid obesity and skeletal Class III. The patient presents with moderate-severe osas associated. Considering the patient's significant respiratory problem, any type of mandibular setback was rejected due to the negative effect on the airway. The patient underwent surgery with a maxillary advancement of 15 mm and a mandibular advancement of 8 mm. The result of the surgery has been stable. The lateral cephalometric radiographs show a significant enlargement of the airway. The photos were taken 2 years later.

Clinical case No. 4

Orthodontist: Dr. Berraquero.

The patient suffers from sequelae of orthognathic surgery at another center. Since then, she has presented severe sleep apnea syndrome with episodes of significant desaturation. The patient underwent surgery involving a maxillary advancement of 9 mm, mandibular advancement of 14 mm through extraoral L osteotomies, performed with cranial vault grafts and extremely rigid fixation; advancement mentoplasty. The result of the surgery is stable, with the disappearance of snoring, drowsiness, and normalization of polysomnographic parameters.

Authors: César Colmenero, Marina Población Subiza, Silvia Rosón Gómez

References:

- Colmenero C, Esteban R, Albariño AB, Colmenero B. Sleep apnea associated with maxillofacial abnormalities. J. Laringol. Otol 1991; 105: 94-100.

- Rama A.N, Tekwani SH, Kushida C.A. Sites of obstruction in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 2002; 112: 1139-44.

- Kribbs NB, Redline S, Smith PL. Objective monitoring of nasal CPAP usage in OSA patients. Sleep Res. 1991; 20: 270.

- Quilleminanlt C, Powell BC. New surgical approaches for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome Sleep. 1984; 7: 1-2.

- Reley RW, Powell NB, Quilleminanlt C. Maxillary, mandibular and hyoid advancement an alternative to tracheostomy in OSA otolaryngology head and neck surgery. 1986; 94: 584-8.

- Robertson CO, Gooddey RH Rejda M. Subjective and objective treatment outcomes of maxillomandibular advancements for the treatment of OSA: Journal of oral maxillofacial surgery. 2005; 63: 148-54.