Orthopedic Traction Devices in Orthodontics: Extraoral Appliances. Headgear, Facial Masks, Chin Cups

Orthopedic traction devices play a vital role in orthodontics, particularly in the correction of complex skeletal discrepancies. Extraoral appliances, such as headgear, facial masks, and chin cups, are designed to influence jaw growth and positioning in growing patients, reducing the need for invasive procedures later. These devices apply controlled forces to guide the development of the maxilla or mandible, addressing Class II and Class III malocclusions effectively.

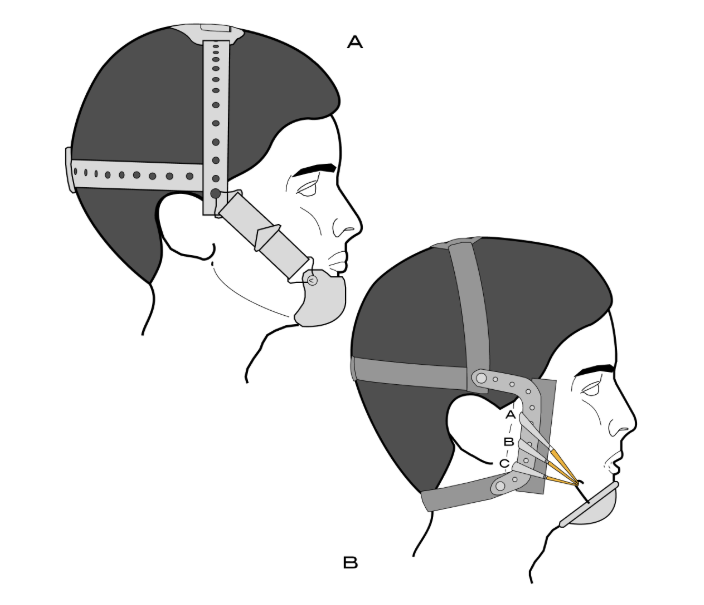

Facial Masks in Orthodontics

Class III malocclusions are among the most intricate orthodontic conditions, involving an anteriorly positioned lower jaw or a retruded upper jaw. These issues, which may include maxillary retrusion or mandibular prognathism (or both), pose significant challenges for both the dental and skeletal structures. However, advancements in orthodontic technology, particularly facemasks, have enabled significant improvements in the skeletal relationship between the upper and lower jaws, especially in growing patients.

Facemasks are extraoral appliances used to apply anteriorly directed forces to the maxilla, typically used alongside Rapid Palatal Expansion (RPE). This combination encourages the forward growth of the upper jaw, effectively addressing Class III malocclusions caused by a retruded maxilla. RPE not only expands the maxilla laterally but also loosens sutures, making it easier for the facial mask to pull the upper jaw forward. After expansion, the expander remains in place as a retainer while the facial mask continues to encourage forward growth.

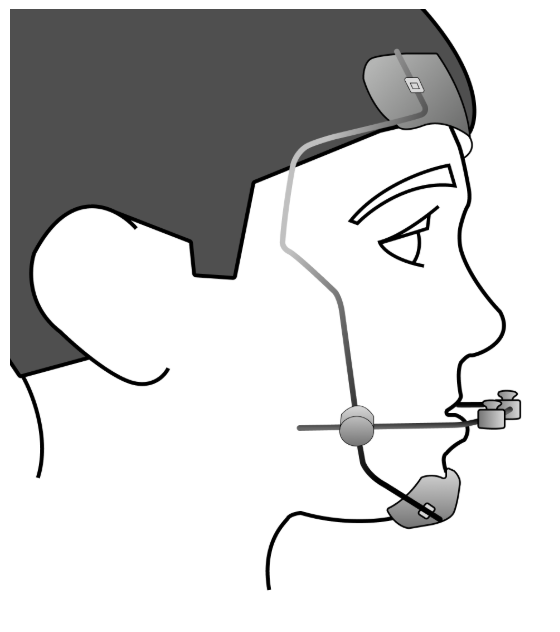

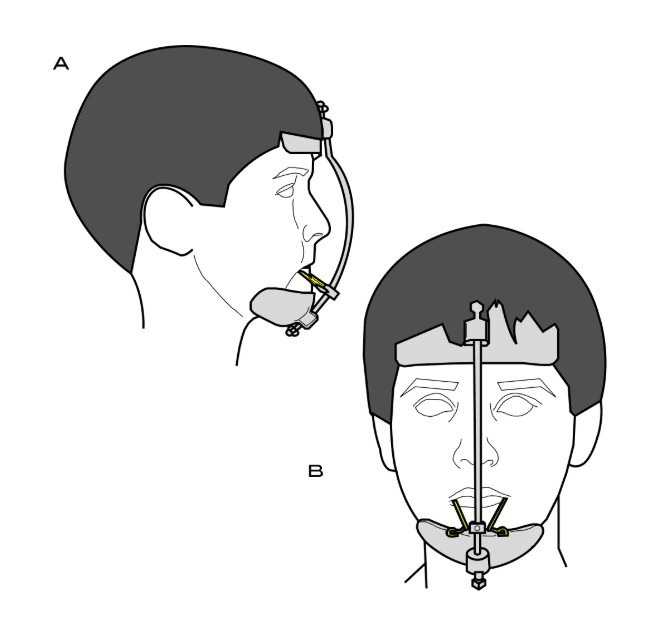

Facemasks work most effectively during the mixed dentition phase, taking advantage of the growth potential in younger patients. A facial mask consists of:

- forehead pad and a chin pad, connected by a steel support rod.

- crossbow that attaches to rubber bands, providing elastic traction on the maxilla to encourage forward and downward movement.

- bonded maxillary splint (often used with a maxillary expansion appliance) to anchor the device.

Face masks for Class III malocclusion are most effective in primary and early mixed dentition. Timing is everything in orthodontics, and early intervention can guide jaw growth, prevent complex malocclusions, and reduce the need for extractions or surgery in the future. We invite you to join Dr. Marco Rosa’s most comprehensive online course “Early Orthodontic Treatment: When and How?”, with which you’ll learn exactly when and how to intervene at the right moment. From rapid palatal expansion to functional appliances, from crossbite correction to managing impacted teeth – this 16-lesson course gives you a precise roadmap for early orthodontic treatment. Master the science of growth prediction, skeletal adaptation, and non-invasive correction to ensure the best outcomes for your young patients.

Facial Masks Mechanism of Action

Facemask therapy works by applying forward and downward forces to the maxilla, which leads to:

- Anterior movement of the maxilla: This addresses maxillary retrusion by shifting the maxilla forward, typically by 1-3 mm, with some cases showing more significant movement.

- Maxillary Dentition Movement: The upper incisors are often pushed forward, helping to correct the overjet.

- Bone Remodeling: The appliance stimulates the maxillary sutures and encourages new bone formation along the stretched connective tissue, aiding in the forward shift of the maxilla.

- Counterclockwise rotation of the maxilla: The posterior nasal spine (PNS) moves more downward than the anterior nasal spine (ANS), helping to reposition the maxillary structure.

- Mandibular changes: As a response to the forces applied, the mandible often rotates in a clockwise direction, causing the chin to move downward and backward, while increasing lower anterior facial height and reducing overbite. Mandibular growth is restricted to some extent during facemask therapy. Both early and late treatment resulted in reduced mandibular protrusion, but early treatment showed significantly smaller increments in mandibular length.

- Vertical Effects: The vertical dimension of the face may also be impacted, with some studies showing an increase in lower anterior facial height.

Types of Facial Masks:

Delaire Mask: The Delaire mask is made up of a metal frame that encircles the patient's face, featuring a horizontal frame with hooks for elastic traction.

Petite Mask: The Petite mask has a central metal frame made of round steel wire with protective caps at the ends. The center features a crossbar made from 0.25mm steel wire, with hooks or bends for elastic traction.

Tübinger Mask: The Tübinger mask comprises a metal frame with two rods running down the center of the face and curving around the patient's nose. It includes a crossbar for rubber traction.

Facial Mask + Braces: In the long term, orthodontic facial masks can flatten the face and hinder forward chin projection, pushing both the upper and lower jaws down and backward, into the airway. Facial masks restrict natural jaw growth and contribute to decreases in SNA and ANB angles, which are key parameters for airway size.

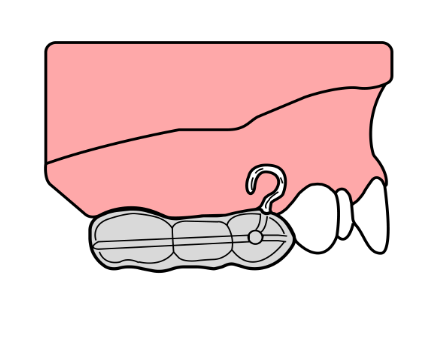

Facial Mask + Mini Plates: Facial masks combined with mini plates offer effective maxillary protraction without significant rotation in a shorter treatment time. The lower jaw demonstrates significantly less posterior rotation, and the increase in lower facial height is less pronounced. The unwanted dentoalveolar effects, such as mesialization and tipping of maxillary teeth and extrusion of molars, are minimized or eliminated by the use of mini plates. Mini-screws are activated by 1/4 mm daily before sleep until the desired maxillary width expansion is achieved. If expansion is not desired, the screw is activated for 8-10 days to break the suture and promote maxillary protraction. Once the patient adapts to wearing the maxillary splint, facial mask therapy begins, utilizing a sequence of elastics with increasing force (200, 350, 600 grams per side) until a significant orthopedic force is applied to the maxillary complex.

Facial Mask Treatment Timing

The ideal time to begin treatment with a facial mask is when the permanent upper central incisors are erupting, while the lower incisors have already emerged into occlusion. Achieving a positive horizontal and vertical overlap during treatment is essential for maintaining the anterior-posterior correction of Class III malocclusion.

Facemasks should ideally be worn for 20 hours a day for 4-6 months, after which they can be worn only at night. Prolonged use beyond 9-12 months is generally discouraged.

Facial Mask Post-Treatment Retention

After removing the facial mask and RME appliance, the patient can be retained using various devices, such as a simple retainer, FR-3 appliance, or chin cup. Since facial masks are typically used during early mixed dentition, a significant amount of time may pass before the final stage of non-removable appliances begins. Multiple orthopedic interventions may be necessary, so such patients should be monitored until the facial growth phase concludes.

Key Findings from Clinical Studies about Usage of Facial Masks in Orthodontics:

- Cephalometric analysis and diagnostic models before and after treatment have shown that facial masks produce minimal skeletal changes in adolescents aged 12-14.

- When selecting the method for dentoalveolar compensation of Class III skeletal anomalies with a facial mask, improvements in the profile are more closely associated with changes in the position of the incisors than the jaws.

- Treating severe Class III skeletal anomalies with dentoalveolar compensation in adolescents does not yield ideal aesthetic results.

- The facial mask does not restrict the growth of the lower jaw; instead, it leads to posterior rotation, improving the facial proportions in patients with hypodivergence, but worsening the proportions in patients with skeletal hyperdivergence. This factor must be considered when choosing an appliance and treatment method.

- Severe Class III malocclusions with large negative overjets (greater than 5 mm) may be less responsive to facemask therapy, especially when mandibular growth is excessive. For milder cases, facemask therapy shows more consistent and predictable results

Facemask therapy, when combined with rapid maxillary expansion, is a highly effective treatment for Class III malocclusions, particularly when initiated during the mixed dentition stage. The therapy provides both skeletal and dental corrections, moving the maxilla forward and achieving Class I molar relationships. While the initial effects are favorable, some relapse may occur due to continued mandibular growth. Long-term results show that the maxilla maintains its anterior position, but slight mandibular compensations may cause minor shifts back towards a Class III pattern. Despite these challenges, facemasks remain a critical tool in early orthodontic intervention for Class III malocclusions.

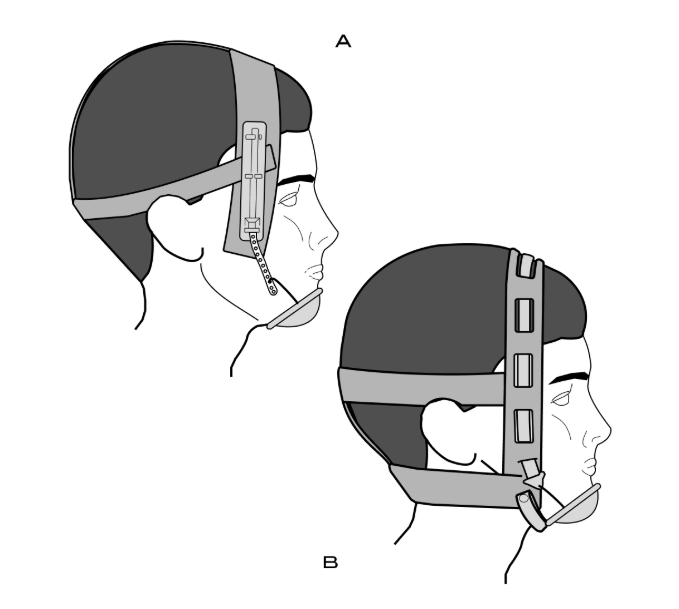

Chin Cups in Orthodontics

Chin cups are among the oldest orthopedic devices used to manage Class III malocclusions, especially those involving mandibular prognathism, where the lower jaw protrudes forward. These devices apply extraoral force to reposition the mandible. There are two main types of chin cups:

- Occipital-Pull Chin Cup: This type is primarily used for correcting mandibular prognathism by applying backward and upward force to the lower jaw.

2. Vertical-Pull Chin Cup: Designed for patients with excessive lower anterior facial height or steep mandibular planes, this device helps limit downward mandibular growth, which can lead to an increase in posterior facial height.

Mechanics and Application of Chin Cups

- Chin cups work by applying external force to the chin, guiding the direction of mandibular growth.

- The Occipital-Pull Chin Cup is most effective in younger patients with mild to moderate mandibular protrusion, especially when used during the mixed dentition phase.

- The force exerted by the chin cup encourages a downward and backward rotation of the mandible, which helps to reduce the prominence of the chin.

Effectiveness and Limitations of Chin Cups

- Mandibular Growth Limitation: The chin cup may slow down the growth of the mandible, though the long-term effects are mixed. Some studies report significant changes in mandibular growth, while others note no long-term effects, especially in patients treated after adolescence.

- Vertical Changes: Chin cups can alter vertical dimensions, often increasing lower anterior facial height. This is particularly useful in patients with a short lower facial height and a high mandibular plane angle.

Aesthetic and Functional Considerations: Chin cups are often less conspicuous than face masks, making them more acceptable to patients, especially during the retention phase.

Comparison of Face Masks and Chin Cups

Face Masks:

- Fast Acting: Produces significant skeletal and dentoalveolar changes within 4-6 months.

- More Visible: May be less acceptable to some patients due to its bulk and the requirement for full-time wear.

- Higher Efficacy in Younger Patients: The most effective when started early in the mixed dentition phase.

- Requires Active Monitoring: Frequent follow-ups are needed to ensure the treatment is proceeding effectively.

Chin Cups:

- Slower Acting: Requires more extended treatment periods compared to face masks, typically up to 12-24 months.

- Less Visible: More comfortable and aesthetically acceptable but less effective in severe cases of mandibular prognathism.

- Long-Term Efficacy: May lead to changes in mandibular growth, particularly in younger patients, but results are often less dramatic than those produced by face masks.

Both face masks and chin cups play crucial roles in the early orthodontic treatment of Class III malocclusions. Face masks are particularly effective for maxillary protraction, providing fast results when used in the early mixed dentition stage. Chin cups, on the other hand, are more suited for managing mandibular prognathism, typically requiring longer treatment periods and offering slower but more sustainable results.

The choice between these appliances depends on the severity of the malocclusion, patient age, and compliance levels. In many cases, a combination of both may be employed to achieve comprehensive correction, with each appliance contributing to different aspects of the malocclusion.

Early intervention with these orthopedic appliances can reduce the need for surgical intervention later in life, though it is important to manage patient expectations, as the timing of treatment and patient cooperation significantly affect the outcome.

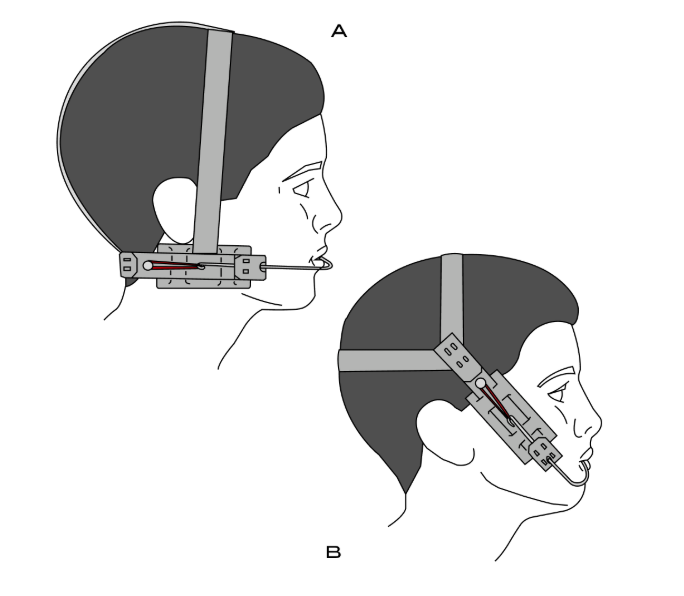

Headgear in Orthodontics

Headgear remains a crucial component in the treatment of Class II malocclusions, where the upper jaw protrudes relative to the lower jaw. This appliance plays a key role in correcting the relationship between the maxilla and mandible by applying force to control the growth of the upper jaw. It is particularly effective in cases with excessive maxillary protrusion or increased vertical growth.

However, the success of headgear treatment heavily depends on patient compliance. Numerous studies have highlighted that inconsistent use of headgear often leads to delays in treatment progress, longer chair time, and suboptimal results. A major challenge in headgear therapy is deciding whether intermittent or continuous force application is more effective for achieving the desired outcome.

Continuous vs. Intermittent Force in Orthodontics

1. Continuous Force Mechanics:

- In orthodontic treatments using continuous force, such as with fixed appliances, the rate of tooth movement is well-understood. The continuous application of force is directly related to the sustained bone resorptive response, which results in steady tooth movement.

- Biological Response: It is well-documented that continuous pressure for a certain duration (typically around 3 hours) is necessary to achieve the maximal displacement of a tooth’s root within the periodontal ligament (PDL), leading to effective tooth movement.

2. Intermittent Force Mechanics – Headgear:

- Intermittent Loads: With appliances like headgear, forces are applied intermittently, typically for around 12 to 14 hours per day (often overnight). The question arises whether this method can achieve the same effectiveness as continuous force application.

- Inconsistencies in Effectiveness: The response to intermittent forces, such as those from headgear, is less predictable and can vary significantly between patients, even when motivation and compliance are optimal. This inconsistency suggests that other physiological factors influence the effectiveness of intermittent force.

Are you curious to master the science of forces in orthodontics? Join the "Biomechanics Fundamentals of Orthodontic Therapy" online course and gain a deep understanding of force systems, tooth movement, and mechanical equilibrium in orthodontics. This course provides a structured approach to mastering force applications for predictable and efficient treatment outcomes. From force vectors, moments, and centers of resistance to torque mechanics, anchorage control, and cantilever applications, you’ll learn how to design precise, stable, and biomechanically sound orthodontic treatments. Through real-world clinical cases and mathematical calculations, you'll develop the expertise to analyze, plan, and apply forces effectively.

The best results are often achieved when headgear is worn continuously for 12 hours per day, ideally overnight, to synchronize with the body's natural circadian rhythm of PDL response. To optimize treatment outcomes, orthodontists should advise their patients to wear headgear without interruption during the daily wear period and to avoid frequent removal, which could compromise the force application needed for effective treatment.

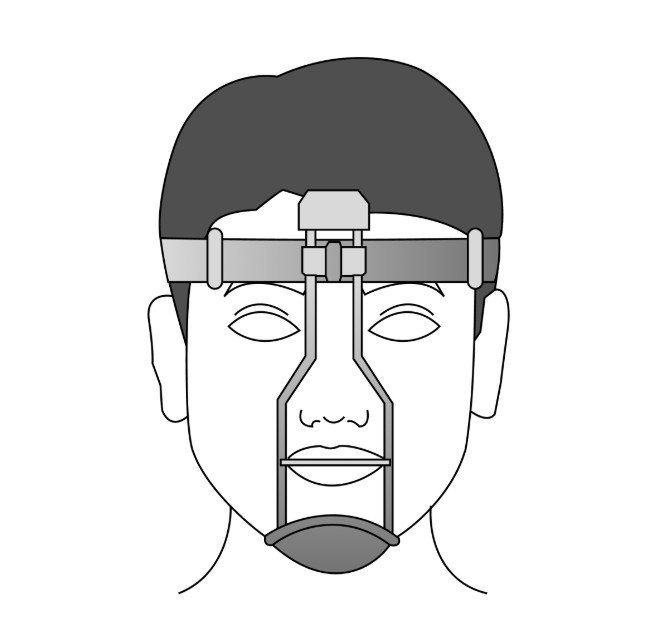

Types of Headgear and Their Applications

Orthodontic headgear comes in various forms, with the cervical headgear and high-pull headgear being the most commonly used appliances for skeletal Class II correction.

- Cervical Headgear:

- The cervical headgear is designed to exert a force that pulls the maxilla downward and backward. It has been shown to create significant orthopedic changes, particularly by tipping the maxillary molars and altering the growth direction of the maxilla. This effect is especially useful for controlling the vertical growth of the maxilla and helping manage cases of vertical dysplasia.

- Research has confirmed that cervical headgear is more effective than high-pull headgear in terms of the intensity of the forces applied. It creates higher stress in areas such as the zygomatic arches, palatal bones, and pterygoid plates, which are critical to the position and development of the maxilla.

- The cervical appliance’s action on the posterior palate can assist in lateral development of the alveolar processes, helping prevent issues like cross-bites during treatment. This effect is particularly beneficial in Class II malocclusions transitioning into a Class I relationship.

- High-Pull Headgear:

- The high-pull headgear applies force to the maxilla in an upward and backward direction. While it does produce stress on craniofacial structures, the force is generally less intense than that produced by cervical headgear. High-pull headgear specifically affects the anterior region of the maxilla, particularly below the anterior nasal spine.

- It has been shown to be less effective in altering the vertical position of the maxilla, especially when compared to cervical headgear. However, it is still valuable in cases where more direct movement of the maxilla is required.

Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Effects

The application of either cervical or high-pull headgear results in the transmission of forces to the deeper structures of the craniofacial complex, including:

- Pterygoid Plates: Both types of headgear produce high stresses at the pterygoid plates of the sphenoid bone. This is significant as the pterygoid plates are a posterior limit for maxillary movement.

- Zygomatic Arches: Both headgear types produce stress in the zygomatic arches, affecting the zygomaticotemporal suture. Cervical headgear generates a more intense force, particularly at lower load levels.

- Maxillary Molars: The forces from both cervical and high-pull headgear are transmitted to the maxillary molars, with cervical headgear exerting more tipping force on the molars compared to high-pull headgear. This force impacts the development of the alveolar bone surrounding the molars.

The posterior palate and zygomaticofrontal sutures also show variable stress under different headgear conditions. Notably, cervical traction tends to separate the palatine bones, which can be beneficial for preventing cross-bites.

Clinical Considerations

When selecting the appropriate headgear for a patient, the following factors should be considered:

- Cervical Traction: Ideal for patients who require significant orthopedic changes, particularly in Class II cases with vertical discrepancies. It is particularly useful for controlling maxillary growth and tipping the molars backward.

- High-Pull Traction: Best suited for patients where the primary concern is to alter the anterior region of the maxilla, such as correcting the overjet or influencing the position of the anterior nasal spine. It is less effective than cervical headgear in altering the overall maxillary position.

In clinical practice, the combination of both cervical and high-pull headgear may provide synergistic effects, where cervical traction can help control the posterior region of the maxilla, and high-pull traction can focus on the anterior region, offering a more balanced approach to the correction of Class II malocclusions.

The Twin Block appliance is commonly used with headgear, this combination helps modify jaw growth more effectively. How Twin Block works:

- A removable functional appliance with upper and lower acrylic plates that have bite ramps (blocks) at a 70° angle.

- Encourages forward growth of the mandible by repositioning it forward during function.

- Promotes dentoalveolar and skeletal changes in growing patients.

The vertical dimension also plays a critical role in ensuring optimal treatment outcomes. Activator and headgear combination therapy appears to increase vertical growth, especially in the mandibular region, which is important for maintaining facial harmony.

The most favorable outcomes of headgear and functional appliance therapy are typically achieved when treatment occurs during the middle to late mixed dentition period, which corresponds to the pubertal growth spurt. At this stage, the mandibular skeletal response is greatest, allowing for maximal skeletal changes and the correction of the Class II malocclusion.

Once the desired results are achieved with headgear, the treatment typically transitions to fixed appliances for further refinement and stabilization. This transition is crucial for maintaining the gains made during the headgear phase while ensuring that the treatment proceeds efficiently. Fixed appliances can work in tandem with functional appliances, ensuring that both dento-alveolar and skeletal changes are retained.

For non-extraction cases, braces and early use of Class II elastics may be preferable, depending on the patient’s specific needs. In cases with a high Frankfurt-mandibular angle or vertical maxillary excess, high-pull headgear can be used, while inclined bite planes or early Class II elastics may be more appropriate for patients with a low Frankfurt-mandibular angle and a deep overbite.

When should you expand the maxilla? When can you avoid extractions? How do you combine fixed and functional appliances for optimal results? Mixed dentition treatment can be challenging – are you making the right decisions at the right time? Join the course “Orthodontics in Growing Patients” and explore the most effective strategies for treating mixed dentition, the proper use of functional and fixed appliances, digital workflows for treatment planning, and the management of complex cases such as deep bite, open bite, and impacted canines.

Comparison Table of Facemask, Occipital-Pull Chin Cup, Vertical-Pull Chin Cup, Cervical Headgear and High-Pull Headgear

Feature | Facial Mask | Occipital-Pull Chin Cup | Vertical-Pull Chin Cup | Cervical Headgear | High-Pull Headgear |

| Primary Function | Maxillary protraction (Class III correction) | Mandibular retrusion (Class III correction) | Reduces lower facial height, vertical control | Maxillary molar distalization, vertical control | Maxillary molar distalization, vertical control |

| Design | Forehead and chin pads connected by support rods with elastics | Chin cup with head strap, occipital pull | Chin cup with head strap, vertical pull | Headgear with neck strap and cheek pads | Headgear with neck strap and high-positioned pads |

| Main Force Application | Forward and downward traction on maxilla | Forces applied to the chin to move mandible backward | Vertical pull on chin, affecting mandibular growth | Forces applied to maxillary molars for distalization | Forces applied to maxillary molars for distalization |

| Primary Use | Class III malocclusion, maxillary retrusion | Class III malocclusion, mandibular prognathism | Class III malocclusion, excessive lower facial height | Class II malocclusion, maxillary molar distalization | Class II malocclusion, maxillary molar distalization |

| Mode of Wear | Full-time wear (20 hours/day), then nighttime wear | Full-time wear (20 hours/day) | Full-time wear (20 hours/day) | Full-time wear (12-16 hours/day) | Full-time wear (12-16 hours/day) |

| Treatment Duration | 4-6 months full-time, then retention phase | 6-12 months depending on severity | 6-12 months depending on severity | 12-18 months depending on malocclusion severity | 12-18 months depending on malocclusion severity |

| Indication | Best in early mixed dentition for Class III correction | Used for mandibular prognathism (Class III) | Used for high mandibular plane angles and vertical control | Best for Class II malocclusion with maxillary protrusion | Best for Class II malocclusion with maxillary protrusion |

| Anchorage | Bonded maxillary splint (expansion or fixed) | Chin cup with occipital head strap | Chin cup with vertical pull mechanism | Cheek pads and neck strap, anchors to maxillary molars | High-positioned pads and neck strap, anchors to maxillary molars |

| Effect on Maxilla | 1-2 mm of forward movement, maxillary protraction | No direct effect on maxilla | No direct effect on maxilla | No direct effect on maxilla | No direct effect on maxilla |

| Effect on Mandible | Downward and backward rotation, reduces mandibular protrusion | Reduces mandibular protrusion by backward rotation | Vertical and downward rotation of mandible | Minimal to no effect on mandible | Minimal to no effect on mandible |

| Age Suitability | Early mixed dentition (before full eruption of maxillary incisors) | Early mixed dentition (Class III with mandibular prognathism) | Early mixed dentition, high mandibular plane angles | Early mixed dentition, late mixed dentition, adolescence | Early mixed dentition, late mixed dentition, adolescence |

| Commonly Used For | Class III malocclusion, maxillary retrusion | Class III malocclusion, mandibular prognathism | Excessive lower facial height, vertical Class III | Class II malocclusion with maxillary protrusion | Class II malocclusion with maxillary protrusion |