Microcomputed tomography analysis of the root canal morphology of single-rooted mandibular canines

Abstract

Aim: To investigate the anatomy of single-rooted mandibular canine teeth using microcomputed tomography (μCT).

Methodology: One hundred straight single-rooted human mandibular canines were selected from a pool of extracted teeth and evaluated using μCT. The anatomy of each tooth (length of the roots, presence of accessory canals and apical deltas, position and major diameter of the apical foramen and distance between anatomical landmarks) as well as the two- and three-dimensional morphological aspects of the canal (area, perimeter, form factor, roundness, major and minor diameter, volume, surface area and structure model index) were evaluated. The results of the morphological analysis in each canal third were compared statistically using Friedman’s test (α = 0.05).

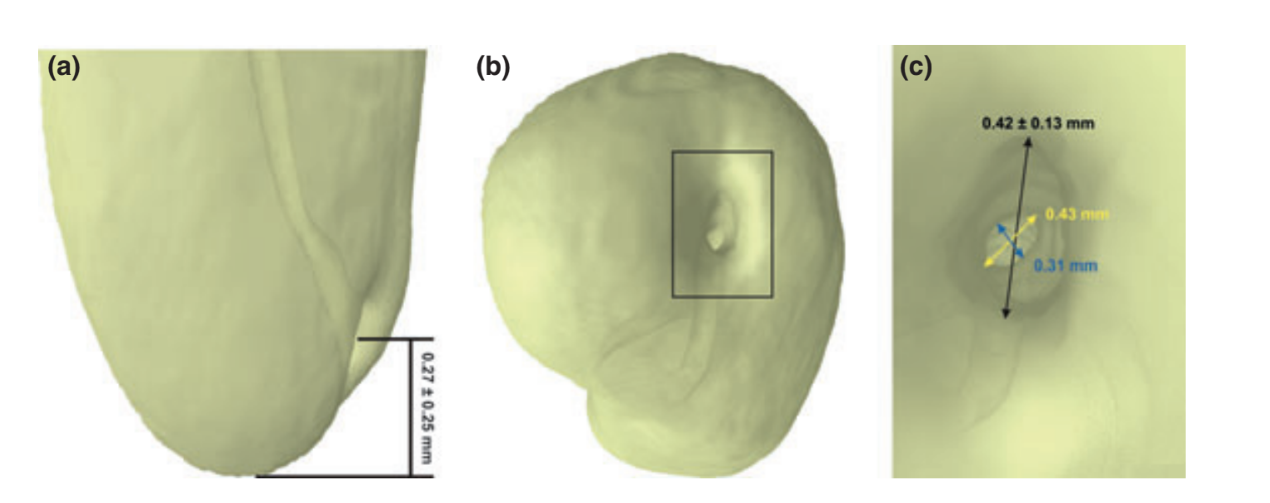

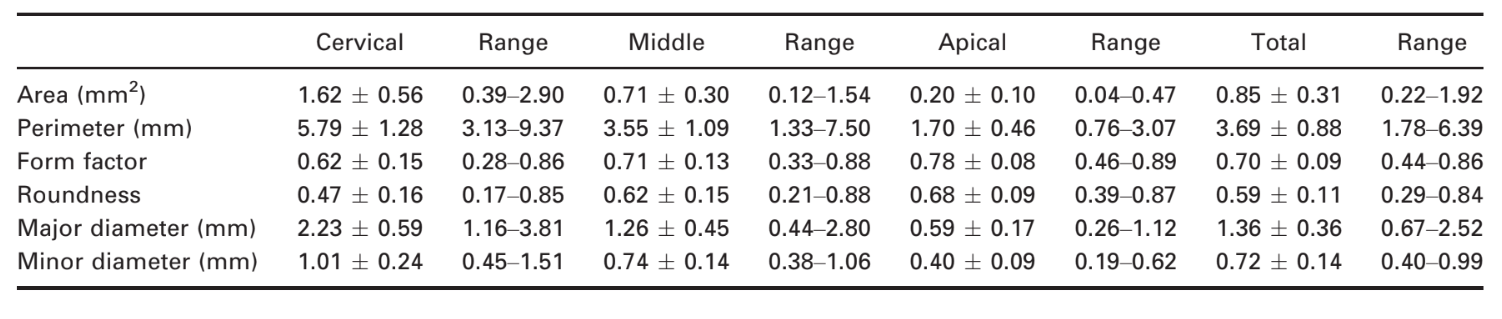

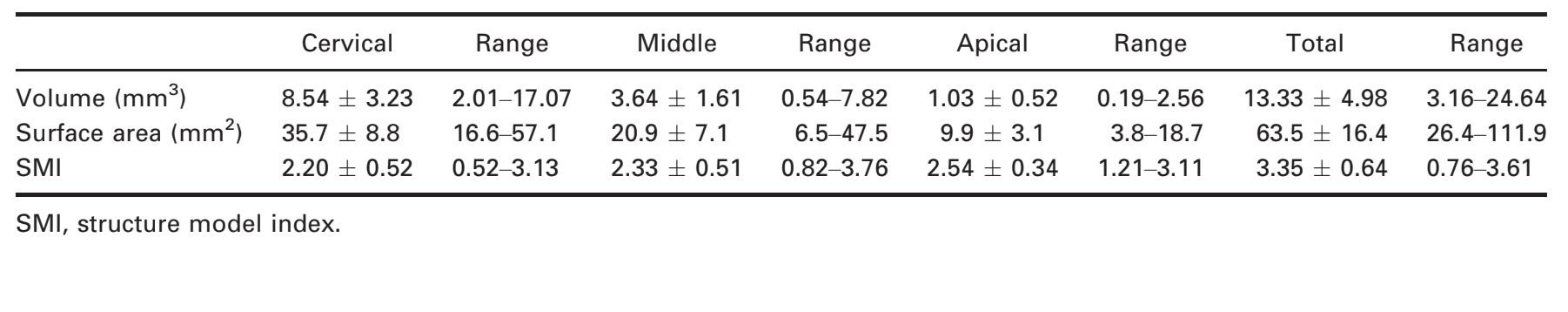

Results: The length of the roots ranged from 12.53 to 18.08 mm. Thirty-one specimens had no accessory canals. The location of the apical foramen varied considerably. The mean distance from the root apex to the major apical foramen was 0.27 ± 0.25 mm, and the major diameter of the major apical foramen ranged from 0.16 to 0.72 mm. Mean major and minor diameters of the canal 1 mm short of the foramen were 0.43 and 0.31 mm, respectively. Overall, the mean area, perimeter, form factor, roundness, major and minor diameters, volume, surface area and structure model index (SMI) were 0.85 ± 0.31 mm2, 3.69 ± 0.88 mm, 0.70 ± 0.09, 0.59 ± 0.11, 1.36 ± 0.36 mm and 0.72 ± 0.14 mm, 13.33 ± 4.98 mm3, 63.5 ± 16.4 mm2 and 3.35 ± 0.64, respectively, with significant statistical difference between thirds (P < 0.05).

Conclusions: The anatomy and morphology of the root canal of single-rooted canines varied widely in different levels of the root.

Introduction

The main role of laboratory-based studies is to develop well-controlled conditions that are able to reliably compare certain factors. The main confounding factor of ex vivo studies is the anatomy of the root canal system under investigation. Consequently, the results might demonstrate the effect of canal anatomy rather than the variable of interest (De-Deus 2012). Generally, the most common method for sample selection in endodontic research has been radiography. However, the accuracy of radiography in assessing the morphology of the root canal system is reduced because it provides only a two-dimensional image of a three dimensional structure (Pascon et al. 2009). Additionally, root canal anatomy has been evaluated using clearing techniques, longitudinal and transverse cross-sectioning and scanning electron microscope (Vertucci 1984). However, these methods are invasive and, therefore, cannot accurately reflect the morphology of the object being studied (Versiani et al. 2011a).

In recent years, microcomputed tomography (μCT) has gained increasing significance in the study of hard tissues in endodontics as it offers a reproducible technique that can be applied quantitatively as well as qualitatively for the three-dimensional assessment of the root canal system (Peters et al. 2001, Versiani et al. 2011a, b, 2012). Consequently, this method might improve the matching of teeth to enhance the internal validity of ex vivo experiments.

In endodontic research, different groups of teeth have been used. Amongst them, the single-rooted mandibular canine has been extensively used for testing materials and techniques (Spångberg 1990). Although its morphology has been investigated previously (De-Deus 1975, Vertucci 1984, Pécora et al. 1993), no research has been undertaken to evaluate its anatomy in detail using high-resolution computed tomography. Thus, considering that a thorough understanding of the variations in root canal morphology of single-rooted canine is essential for its experimental use in endodontic research, as well as for overcoming problems related with shaping and cleaning procedures, the purpose of this ex vivo study was to investigate the root canal anatomy of extracted single-rooted human mandibular canine teeth using microcomputed tomography.

Materials and methods

After ethics committee approval, one hundred straight single-rooted human mandibular canine teeth with fully formed apices and a single root canal were randomly selected from a pool of extracted teeth, decoronated, and stored in labelled individual plastic vials containing 0.1% thymol solution. After being washed in running water for 24 h, each tooth was dried, mounted on a custom attachment and scanned in a μCT scanner (SkyScan 1174v2; Bruker-microCT, Kontich, Belgium) at an isotropic resolution of 19.6 μm.

Images of each specimen were reconstructed from the apex to the level of the cemento-enamel junction with dedicated software (NRecon v. 1.6.3; Bruker-microCT), providing axial cross sections of the inner structure of the samples. For each tooth, evaluation was performed for the full canal length (approximately 790 slices) totalling up to 79 035 slices. Data-Viewer v. 1.4.4 software (Bruker-microCT) was used to evaluate the length of the roots, the presence of accessory canals and apical deltas, the position of the major apical foramen and distance between several anatomical landmarks at the apex. The major diameter of the major apical foramen as well as the buccolingual and mesio-distal diameters of the root canal 1 mm short of the apical foramen was also measured. CTAn v. 1.12 software (Bruker-microCT) was used for the two-dimensional (area, perimeter, form factor, roundness, major diameter and minor diameter) and three-dimensional (volume, surface area and structure model index) evaluation of the root canal.

Area and perimeter were calculated using the Pratt algorithm (Pratt 1991). The cross-sectional appearance, round- or more ribbon-shaped, was expressed as roundness and form factor. Roundness of a discreet two-dimensional object is defined as 4.A/(p.[dmax]2), where ‘A’ is the area and ‘dmax’ is the major diameter. The value of roundness ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 signifying a circle. The form factor is calculated by the equation (4.p.A)/P2, where ‘A’ and ‘P’ are object area and perimeter, respectively. Elongation of individual objects results in smaller values of form factor. The major diameter was defined as the distance between the two most distant pixels in that object. The minor diameter was defined as longest chord through the object that can be drawn in the direction orthogonal to that of the major diameter. Volume was calculated as the volume of binarized objects within the volume of interest. For the measurement of the surface area of the three-dimensional multilayer data set, two components to surface measured in a two-dimensional plane were used; first the perimeters of the binarized objects on each cross-sectional level and second the vertical surfaces exposed by pixel differences between adjacent cross sections. Structure model index (SMI) involves a measurement of surface convexity in a three-dimensional structure. SMI is derived as 6.((S’.V)/S2), where S is the object surface area before dilation and S’ is the change in surface area caused by dilation. V is the initial, undilated object volume. An ideal plate, cylinder and sphere have SMI values of 0, 3 and 4, respectively (Hildebrand & Ru€egsegger 1997). CTVox v. 2.4 and CTVol v. 2.2.1 software (Bruker-microCT) were used for visualization and qualitative evaluation of the specimens.

The results of two- and three-dimensional analyses of each third of the root canal were compared statistically using Friedman’s test with the significance level set as 5%. Data analysis was performed with SPSS v. 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

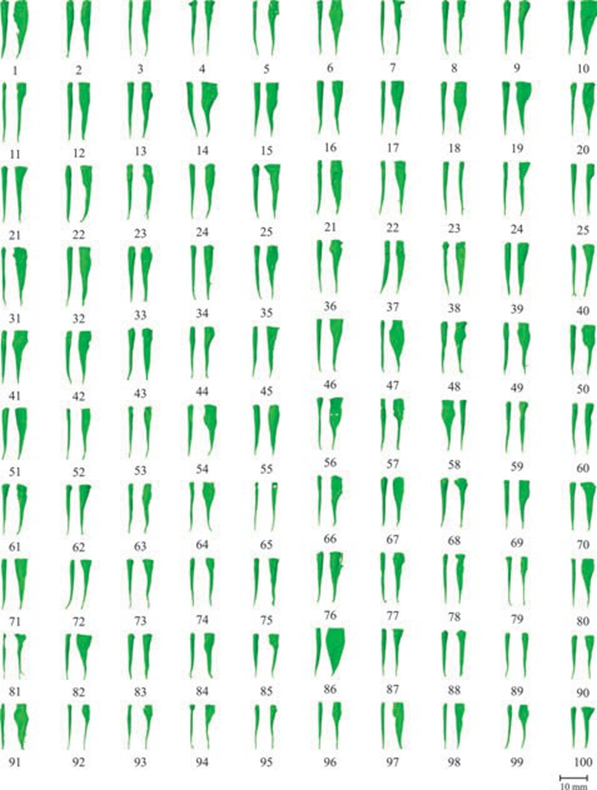

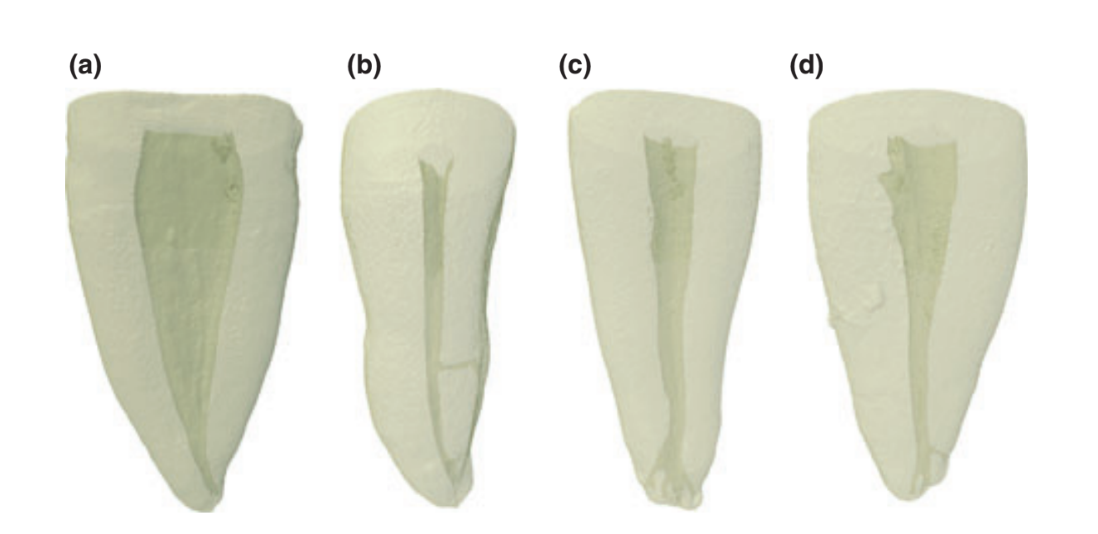

Three-dimensional reconstruction of the internal anatomy revealed that all specimens had only one main root canal (Fig. 1). The length of the roots measured from the apex to the cemento-enamel junction at the buccal aspect of the root ranged from 12.53 to 18.08 mm (15.57 ± 1.20 mm). Thirty-one specimens had no accessory canals (Fig. 2a), and four specimens had a lateral canal in the middle third (Fig. 2b). No accessory canals were observed in the cervical third of the samples, and apical deltas were observed in six specimens (Fig. 2c). In 62 canines, the number of accessory canals in the apical third ranged from 1 to 3, in a total of 112 canals (Fig. 2d).

The location of the major apical foramen varied considerably, tending to the disto-buccal (26%), distal (24%) and buccal (22%) aspects of the root. In five specimens, the apical foramen coincided with the anatomical apex, but the position of the foramen also occurred at the lingual (12%) and disto-lingual (11%) aspects of the root.

Mean sizes and distances (± SD) between reference landmarks at the apex are shown in Fig. 3. The perpendicular distance from the root apex to the major apical foramen ranged from 0 to 1.06 mm (0.27 ± 0.25 mm). The major diameter of the major apical foramen was 0.42 ± 0.13 mm, ranging from 0.16 to 0.72 mm. The bucco-lingual diameter of the root canal 1 mm short of the apical foramen ranged from 0.26 to 0.52 mm (mean of 0.43 mm) and was longer than its mesio-distal diameter that ranged from 0.19 to 0.41 mm (mean of 0.31 mm).

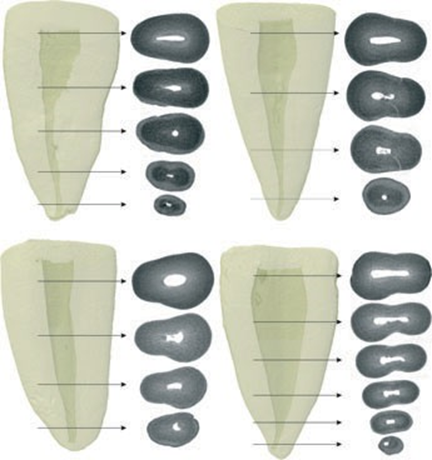

The results of two- (area, perimeter, form factor, roundness, and major and minor diameter) and three-dimensional (volume, surface area, and SMI) analysis are detailed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Significant statistical difference between cervical, middle and apical thirds was observed in all analysed data (P < 0.05). In the apical third, area, perimeter, major diameter, minor diameter, volume and surface area were significantly lower, whilst form factor, roundness and SMI were significantly higher than in the middle and cervical thirds (P < 0.05). Figure 4 shows the two-dimensional configuration of the root canal demonstrating that its cross-sectional appearance varied in different levels of the root in a same tooth, including round, oval, flat and irregular shapes.

Discussion

Knowledge of root canal anatomy and its variations is a basic requirement for successful root canal treatment (Vertucci 2005). The significance of canal anatomy has been emphasized by studies demonstrating that variations in canal geometry before cleaning and shaping had a greater effect on the changes that occurred during preparation than did the instrumentation techniques (Peters et al. 2001). The main purpose of this study was to evaluate mandibular canines with a single root canal that extended from the pulp chamber to the apex (type I) (Vertucci 1974). It has been reported that the prevalence of type I root canal configuration in mandibular canines ranged from 78% to 98% of the sample (Vertucci 1984, Pécora et al. 1993), but occasionally, it may have two roots and two canals (Versiani et al. 2011a).

Although canines are the longest teeth in the mouth, an enormous variation in its size and shape has been reported (Pécora et al. 1993, Woelfel & Scheid 2002). In the present study, the length of the roots ranged from 12.53 to 18.08 mm (15.57 ± 1.20 mm). These results are similar to Woelfel and Scheid (2002) who reported a mean length of 15.9 mm (9.5–22.2 mm) on 316 mandibular canines.

An accessory canal has been defined as any branch of the main pulp canal or chamber that communicates with the external surface of the root, whilst an apical delta is the presence of multiple accessory canals at or near the apex (American Association of Endodontists 2012). In the present study, 69% of the sample had accessory canals located at the middle (n = 4) and apical thirds (n = 65). Apical deltas were observed only in 6% of the sample. De-Deus (1975) investigated the frequency, location and direction of the accessory canals in 1140 human teeth using clearing technique. He found that only three out of 44 mandibular canines (6.8%) had one or two accessory canals. Using the same method, Vertucci (1984) evaluated one hundred mandibular canines and found apical deltas in six teeth and accessory canals in 30% of the sample, located at the cervical (n = 1), middle (n = 5) and apical (n = 24) thirds. Such differences could be explained through differences in sample origin or racial factors, as well as the evaluation methods. However, these results confirm the evidence that, in mandibular canines, accessory canals are most prevalent in the apical third (Vertucci 1984).

The classic concept of apical root anatomy is based on three anatomical and histological landmarks: the apical constriction, the cemento-dentinal junction and the apical foramen (Kuttler 1955). Although, theoretically, it is desirable to prepare the canal to the apical constriction (Ricucci & Langeland 1998), this landmark presents morphological variations that make its identification unpredictable (Dummer et al. 1984). In the present study, the traditional single constriction was observed in 52% of the sample. This result is supported by previous studies on different groups of teeth, using microscopy (Dummer et al. 1984) and micro-CT (Meder-Cowherd et al. 2011), in which different types of apical constriction were observed.

In the present study, the distance from the apex to the major foramen ranged from 0 to 1.06 mm (0.27 0.25 mm), and the eccentric placement of the major foramen was recognized in almost all specimens (95%), often lying on the buccal aspect of the root, as previously observed (Kuttler 1955, Chapman 1969, Burch & Hulen 1972, De-Deus 1975, Dummer et al. 1984, Blasković-Subat et al. 1992, Pécora et al. 1993, Vertucci 2005, Martos et al. 2009, 2010). In the literature, the mean distance between the major apical foramen and the anatomical root apex in mandibular canines has been reported to be 0.35 mm (Green et al. 1956), 0.47 ± 0.35 mm (Dummer et al. 1984), and 0.42 ± 0.32 mm (Martos et al. 2009), which were higher than the present results. These dissimilarities are probably related to sample origin, racial factors and the evaluation methods. Radio- graphically, an apical foramen located buccally or lingually is superimposed over the root structure, making it difficult to view the exit point of the instrument (Nekoofar et al. 2006, Martos et al. 2009, 2010). Therefore, the displacement of the major foramen has the potential to cause an incorrect measurement of the canal and might result in over-instrumentation during root canal preparation (Kuttler 1955, De-Deus 1975, Dummer et al. 1984, Wu et al. 2000, Nekoofar et al. 2006).

The location of the cemento-dentinal junction varies considerably. In general, it is located approximately 1 mm from the major foramen and may not coincide with the apical constriction (Nekoofar et al. 2006). Its diameter also varies extensively and was determined to be 298 μm for canines (Ponce & Vilar Fernandez 2003). In the present study, the mean bucco-lingual and mesio-distal diameters of the root canal 1 mm from the apical foramen were 0.43 and 0.31 mm, respectively. These results are in accordance with Wu et al. (2000) who also investigated canal diameters in the apical region of mandibular canines and found that the mean bucco-lingual and mesio-distal diameters 1 mm short of the major foramen were 0.47 and 0.36 mm, respectively. These results have definite implications for shaping and cleaning procedures because only the mesio-distal diameter is evident on radiographs. Besides, it shows that the size of the root canal 1 mm short of the major foramen in mandibular canines is similar to the diameter of size 35–45 K-files.

The diameter of the major apical foramen has been thought to be the most important factor that influences the performance of electronic apex locators for measuring working length (Nekoofar et al. 2006). In the present study, the mean size of the major apical foramen was similar to the tip of a size 40 K-file (0.42 0.13 mm), but ranged from 0.16 to 0.72 mm. Green (1956) also studied the anatomy of the root apex of 50 mandibular canine and found the apical diameter similar to a size 30 K-file. Considering that the sample was collected at random, this variation might be related to the physiological and pathological conditions of the teeth at the time of extraction (Martos et al. 2009, 2010).

Overall, the qualitative evaluation (Fig. 1) showed that the root canal of mandibular canines were wider mesiodistally than buccolingually. This condition was more evident in the cervical third in comparison with the middle and apical thirds. The area, perimeter, volume and surface area results reflected this morphological feature because they were significantly higher in the cervical than in the middle and apical thirds. Unfortunately, these results cannot be compared with others as there is no information on this subject in the literature to date. Thus, the clinical relevance of such findings is still to be determined. However, these morphological parameters should be taken into consideration when selecting a sample in laboratory-based studies because variations in canal geometry have been considered to affect the results of such studies (Peters et al. 2001).

Canals may have different shapes in cross section in different levels of the root in a same tooth (Wu et al. 2000). Recesses in flat-, irregular- or oval-shaped canals may not be included in a round preparation created by rotation of instruments, and thus, they remain unprepared (Wu et al. 2000, Vertucci 2005, Versiani et al. 2011b). In the present study, the cross-sectional appearance was evaluated using two morphometric parameters: form factor and roundness. Overall, the results showed that whilst form factor diminished from the apical to the cervical third, the roundness increased. It means that the root canal at the apical third was more round or slightly oval in shape in comparison with the middle and cervical thirds. It is interesting to note that the results of this study were no different from those obtained with conventional methods (Wu et al. 2000). Nonetheless, algorithms used in μCT evaluation allow a description of the shape of the root canal mathematically. In this way, the most important data regarding the cross-sectional appearance of the root canals were its variation. The minimum and maximum values of roundness and form factor in all thirds were similar, despite the significance difference of the means observed between the thirds. It means that the same canal may have different cross-sectional forms throughout the root.

The SMI describes the plate- or cylinder-like geometry of an object (Hildebrand & Rüegsegger 1997) and has been used to assess root canal geometry (Peters et al. 2000, Versiani et al. 2011a,b, 2012). The SMI is determined by an infinitesimal enlargement of the surface, whilst the change in volume is related to changes of surface area, that is, to the convexity of the structure. These three-dimensional data are impossible to achieve using conventional techniques such as radiographs or grinding. If a perfect plate is enlarged, the surface area does not change, yielding an SMI of zero. However, if a rod is expanded, the surface area increases with the volume and the SMI is normed so that perfect rods are assigned SMI score of 3 (Peters et al. 2000). Overall, the mean SMI ranged from 2.20 to 2.54, which indicates that the root canal systems had a conical frustum-like geometry. However, a large discrepancy between the minimum and maximum values of SMI in all thirds was also observed (0.52–3.61). If these dissimilarities of the morphological parameters in each third were not taken into consideration during the sample selection in ex vivo studies, it might compromise the results.

Ex vivo experiments have been frequently used to evaluate materials and techniques in dentistry. In endodontics, a variety of teeth have been used in laboratory-based experiments including maxillary central incisors, premolars, molars and canines. The reproduction of the clinical situation might be regarded as the major advantage of the use of extracted human teeth. On the other hand, the wide range of variations in three-dimensional root canal morphology makes standardization difficult (Hülsmann et al. 2005). Thus, if selection bias is not taken into account when the sample is selected, then certain conclusions drawn might be incorrect. On the basis of μCT data, it should be possible to further improve sample selection using established morphological parameters to provide a consistent baseline. As the state of current knowledge on root canal anatomy advances rapidly, the clarification of the purposes of sample selection protocols may assist investigators in the field to arrive at meaningful conclusions (De-Deus 2012).

Conclusions

The anatomy and morphology of the root canal of single-rooted canine varied widely in different levels of the root. In summary:

The mean length of mandibular canine roots was 15.57 ± 1.20 mm;

No accessory canals were observed in the cervical third, and apical deltas were observed only in 6% of the sample;

The location of the major apical foramen varied considerably, tending to the buccal aspect of the root;

- The mean distance from the root apex to the major apical foramen was 0.27 0.25 mm;

- The mean size of the major apical foramen was 0.42 ± 0.13 mm;

In the apical third, area, perimeter, major diameter, minor diameter, volume and surface area were significantly lower, whilst form factor, roundness and SMI were significantly higher than in the middle and cervical thirds.

Authors: M. A. Versiani, J. D. Pécora & M. D. Sousa-Neto

References

- American Association of Endodontists (2012) Glossary of Endodontics Terms, 8th edn. Chicago: American Association of Endodontists.

- Blasković-Subat V, Maricić B, Sutalo J (1992) Asymmetry of the root canal foramen. International Endodontic Journal 25, 158–64.

- Burch JG, Hulen S (1972) The relationship of the apical foramen to the anatomic apex of the tooth root. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology 34, 262–8.

- Chapman CE (1969) A microscopic study of the apical region of human anterior teeth. Journal of the British Endodontic Society 3, 52–8.

- De-Deus QD (1975) Frequency, location, and direction of the lateral, secondary, and accessory canals. Journal of Endodontics 1, 361–6.

- De-Deus G (2012) Research that matters – root canal filling and leakage studies. International Endodontic Journal 45, 1063–4.

- Dummer PM, McGinn JH, Rees DG (1984) The position and topography of the apical canal constriction and apical foramen. International Endodontic Journal 17, 192–8.

- Green D (1956) A stereomicroscopic study of the root apices of 400 maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology 9, 1224–32.

- Hildebrand T, Rüegsegger P (1997) Quantification of bone micro architecture with the structure model index. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering 1, 15–23.

- Hülsmann M, Peters OA, Dummer PMH (2005) Mechanical preparation of root canals: shaping goals, techniques and means. Endodontic Topics 10, 30–76.

- Kuttler Y (1955) Microscopic investigation of root apexes. Journal of American Dental Association 50, 544–52.

- Martos J, Ferrer-Luque CM, Gonzalez-Rodriguez MP, Castro LA (2009) Topographical evaluation of the major apical foramen in permanent human teeth. International Endodontic Journal 42, 329–34.

- Martos J, Lubian C, Silveira LF, Suita de Castro LA, Ferrer Luque CM (2010) Morphologic analysis of the root apex in human teeth. Journal of Endodontics 36, 664–7.

- Meder-Cowherd L, Williamson AE, Johnson WT, Vasilescu D, Walton R, Qian F (2011) Apical morphology of the palatal roots of maxillary molars by using micro-computed tomography. Journal of Endodontics 37, 1162–5.

- Nekoofar MH, Ghandi MM, Hayes SJ, Dummer PMH (2006) The fundamental operating principles of electronic root canal length measurement devices. International Endodontic Journal 39, 595–609.

- Pascon EA, Marrelli M, Congi O, Ciancio R, Miceli F, Versiani MA (2009) An in vivo comparison of working length determination of two frequency-based electronic apex locators. International Endodontic Journal 42, 1026–31.

- Pécora JD, Sousa Neto MD, Saquy PC (1993) Internal anatomy, direction and number of roots and size of human mandibular canines. Brazilian Dental Journal 4, 53–7.

- Peters OA, Laib A, Rüegsegger P, Barbakow F (2000) Three-dimensional analysis of root canal geometry by high-resolution computed tomography. Journal of Dental Research 79, 1405–9.

- Peters OA, Laib A, Gohring TN, Barbakow F (2001) Changes in root canal geometry after preparation assessed by high-resolution computed tomography. Journal of Endodontics 27, 1–6.

- Ponce EH, Vilar Fernandez JA (2003) The cemento-dentinocanal junction, the apical foramen, and the apical constriction: evaluation by optical microscopy. Journal of Endodontics 29, 214–9.

- Pratt WK (1991) Digital Image Processing, 2nd edn. New York: Wiley.

- Ricucci D, Langeland K (1998) Apical limit of root canal instrumentation and obturation, part 2. A histological study. International Endodontic Journal 31, 394–409.

- Spångberg LSW (1990) Experimental Endodontics. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press.

- Versiani MA, Pécora JD, Sousa-Neto MD (2011a) The anatomy of two-rooted mandibular canines determined using micro-computed tomography. International Endodontic Journal 44, 682–7.

- Versiani MA, P´ecora JD, Sousa-Neto MD (2011b) Flat-oval root canal preparation with self-adjusting file instrument: a micro-computed tomography study. Journal of Endodontics 37, 1002–7.

- Versiani MA, P´ecora JD, Sousa-Neto MD (2012) Root and root canal morphology of four-rooted maxillary second molars: a micro-computed tomography study. Journal of Endodontics 38, 977–82.

- Vertucci FJ (1974) Root canal anatomy of the mandibular anterior teeth. Journal of American Dental Association 89, 369–71.

- Vertucci FJ (1984) Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology 58, 589–99.

- Vertucci FJ (2005) Root canal morphology and its relationship to endodontic procedures. Endodontic Topics 10, 3–29. Woelfel JB, Scheid RC (2002) Dental Anatomy: Its Relevance to Dentistry, 6th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Wu MK, R’Oris A, Barkis D, Wesselink PR (2000) Prevalence and extent of long oval canals in the apical third. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics 89, 739–43.