A comparative histological evaluation of the biocompatibility of materials used in apical surgery

Abstract

Aim: To evaluate the biological properties of a variety of materials that could be used in apical surgery.

Methodology: The intraosseous implant technique recommended by the FDI (1980) and ADA (1982) was used to test the following materials: zinc oxide-eugenol (ZOE), mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA), and Z-100 light-cured composite resin. Thirty guinea-pigs, 10 for each material, divided into experimental periods of 4 and 12 weeks, received one implant on each side of the lower jaw symphysis. The connective tissue response alongside the lateral wall outside the cup served as a negative control for the technique. At the end of the observation periods, the animals were killed and the specimens prepared for routine histological examination to evaluate their biocompatibility.

Results: The reaction of the tissue to the materials diminished with time. The ZOE cement was highly toxic during the 4-week experimental period, but this profile changed significantly after 12 weeks, when it showed biocompatible characteristics. MTA and Z-100 showed biocompatibility in this test model at both time periods.

Conclusions: MTA and Z-100 composite were biocompatible at 4 and 12 weeks in this experimental model.

Introduction

Success in root canal treatment depends on the removal of the infected canal contents, followed by canal filling using a material of adequate compatibility to avoid irritation to the periapical tissues. Despite the constant evolution of concepts, new endodontic techniques and the development of more effective materials and instruments, the resolution of periapical pathosis is sometimes only achieved through surgical procedures (Tassery et al. 1999).

Apical surgery, however, should only be carried out when conventional root canal treatment has failed. The ideal material for apical root-end filling should have biocompatible characteristics, dimensional stability, adhesiveness, low solubility and the capacity to create a seal of the apical third of the canal to isolate the root canal system from the periapical region (Gartner & Dorn 1992). Biocompatibility has been demonstrated to be one of the most important factors (Pascon et al. 2001).

When considering the biological properties of endodontic materials, there are a broad range of characteristics that should be considered. The methodologies to evaluate these parameters comprise initial tests, secondary tests and usage studies. The initial evaluation should comprise basic in vitro methods of assessing the biological properties. The secondary assessments should be performed in vivo in laboratory animals and can include implantation experiments. The usage studies are carried out in primates or human beings (Spångberg 1969, Stanley 1985).

A large number of materials have been recommended for apical root-end filling. The aim of this study was to evaluate the tissue reaction of a variety of potentially useful materials used as a root-end filling using the experimental model recommended by the FDI (1980) and ADA (1982).

Materials and methods

The materials evaluated were zinc oxide-eugenol (ZOE) (S.S.White, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) (ProRootTM MTA; Dentsply Endodontics, Tulsa, OK, USA), and Z-100 light-cured composite resin (3M, St Paul, MN, USA). All materials were prepared in the manner advised by the manufacturer for their clinical use, and loaded into Teflon® carriers (Polytetrafluorethylene; DuPont, HABIA, Knivsta, Sweden), ensuring that air was not entrapped.

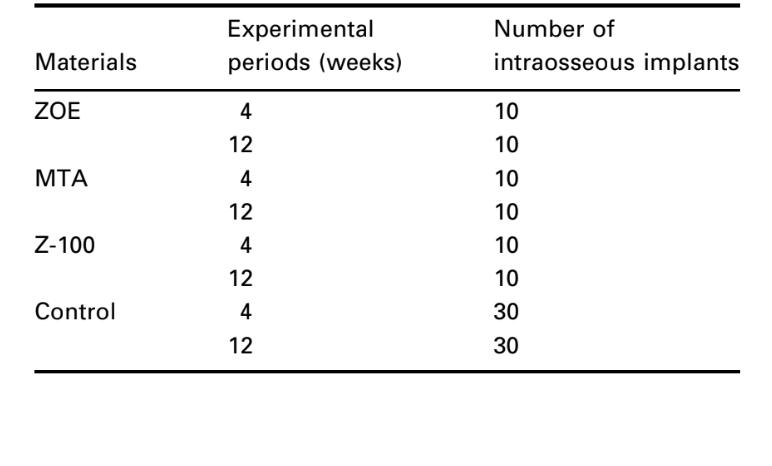

The intraosseous implant in the guinea-pig mandible (Spångberg 1969) and the standardized methods to evaluate the biological reactions recommended by the FDI (1980) and ADA (1982) were used. Thirty guinea-pigs (weighing ~800 g) were selected and each animal received two implants of the same material. Ten specimens were used to each material and observation period (Table 1). Additionally, the connective tissue response alongside the lateral wall outside the Teflon® cup served as a negative control for the technique.

The animals were anaesthetized intraperitoneally with 0.6 mL ketamine (100 mg mL–1), containing acepromazine (0.5 mg mL–1). In the mucobuccal fold of the mandibular incisors region, 0.6 mL xylocaine 2% with epinephrine (1 : 100 000) was injected, to prevent local discomfort. The guinea-pigs were shaved in the submandibular area, and the skin disinfected with 5% tincture of iodine. The distal ventral symphyseal region of mandible was exposed surgically under antiseptic conditions through an incision into the skin and muscle tissue. The mandibular bone on both sides of the symphysis was exposed, and cylindrical holes widened to a diameter of 2 mm and a depth of 2 mm were prepared with burs under sterile physiological saline irrigation. Sterilized cylindrical Teflon® cups, open at one end, and with their outer surfaces threaded to provide retention grooves, were filled under sterile conditions with the materials and inserted into the bony cavities in such a way that the filling materials were in contact with bony tissue. The cylinders were

2.0 mm long and had an inner diameter of 1.3 mm and an outer diameter of 2.0 mm. When the cups were in place, the soft tissues were replaced and sutured independently with a 3-0 resorbable material. The observation periods were 4 and 12 weeks, when the guinea-pigs were killed, the mandible was dissected out and the bone adjacent to the cups in situ sectioned in 10-mm blocks. The specimens were immersed in 10% buffered formalin solution and prepared for routine histological examination. Serial sections (5 lm thick) were cut and stained with haematoxylin–eosin (H & E) for cellular recognition.

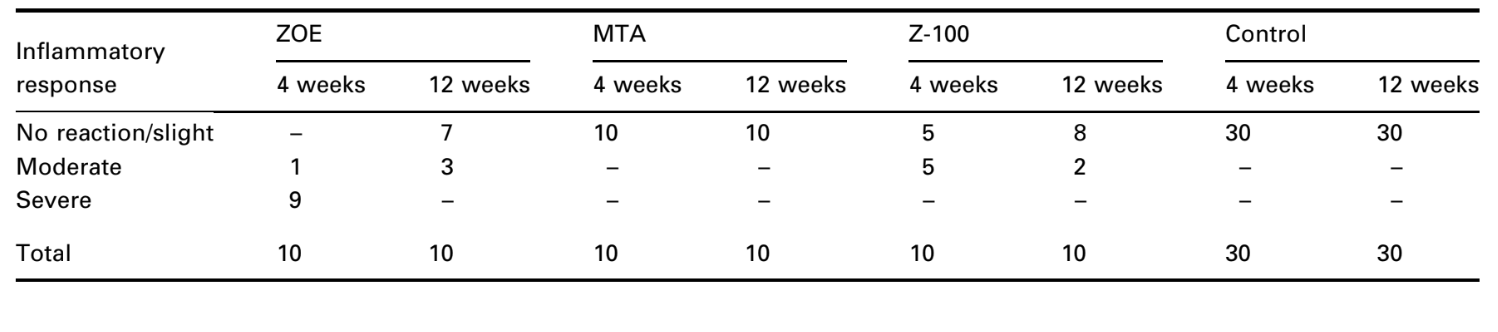

The interface at the opening of the cup, between the material and the bone, was examined and evaluated for the intensity of inflammation. Ten histological criteria were used to determine the inflammatory levels – presence or absence of neutrophilic leucocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, giant foreign body cells, dispersed material, capsule, newly formed healthy bone, necrotic tissue and resorption.

Two independent observers were used to evaluate the tissue reactions. The overall level of the tissue reaction was then rated as none to slight, moderate, and severe according to the histological criteria defined previously. It was considered biologically acceptable that the material showed none to slight reaction at both experimental periods of 4 and 12 weeks, or a moderate reaction at 4 weeks that diminished at 12 weeks.

Results

The number of intraosseous implants and the intensity of inflammatory response are presented in Table 2. The histological evaluations of the materials at 4 and 12 weeks are summarized in Table 3.

Four-week observations

Negative control

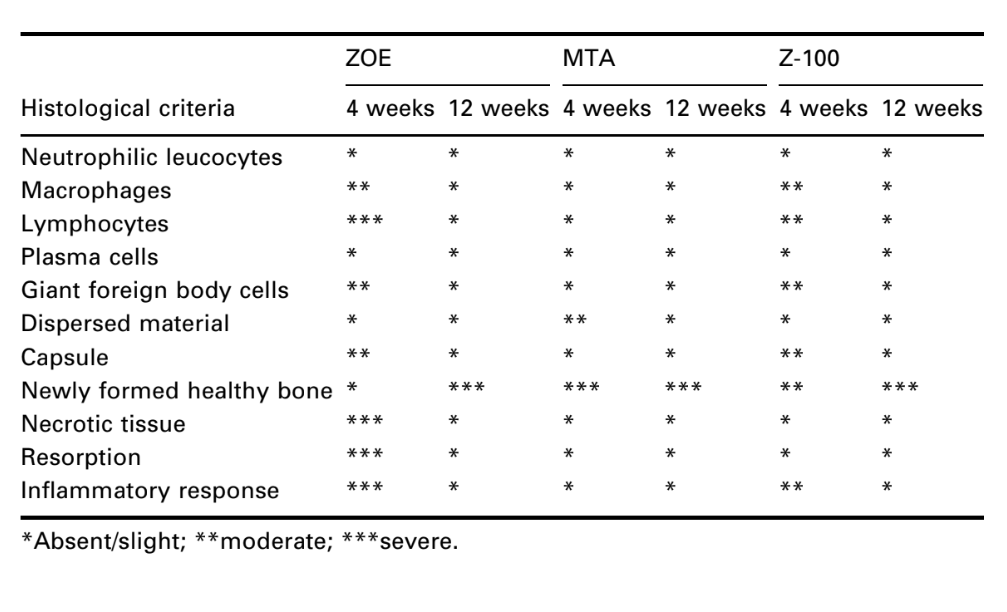

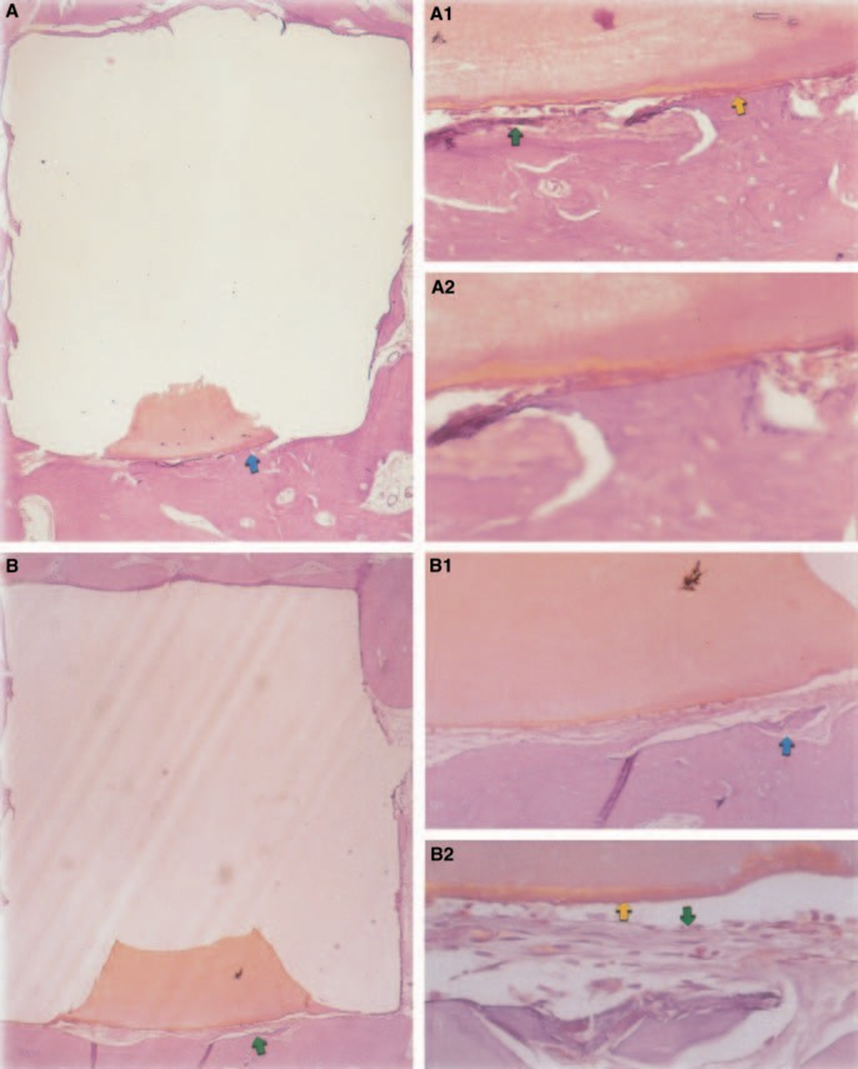

The connective tissue response alongside the lateral wall outside the Teflon® cups of all specimens served as a negative control for the technique. The grooves in the outer surface of the cups were filled with new bone tissue, and thin layers of connective tissue without inflammatory reaction could be seen between the cup and bone at all observation periods in all specimens (Fig. 6A1,A2).

Zinc oxide-eugenol

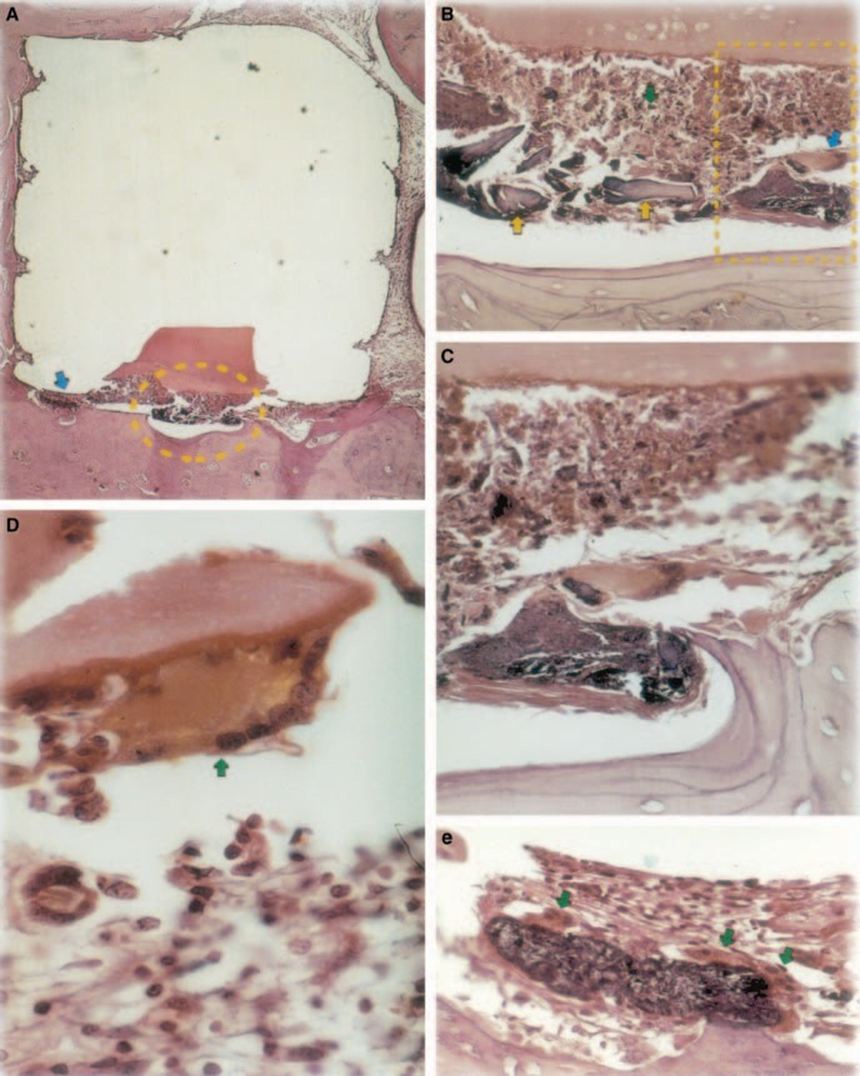

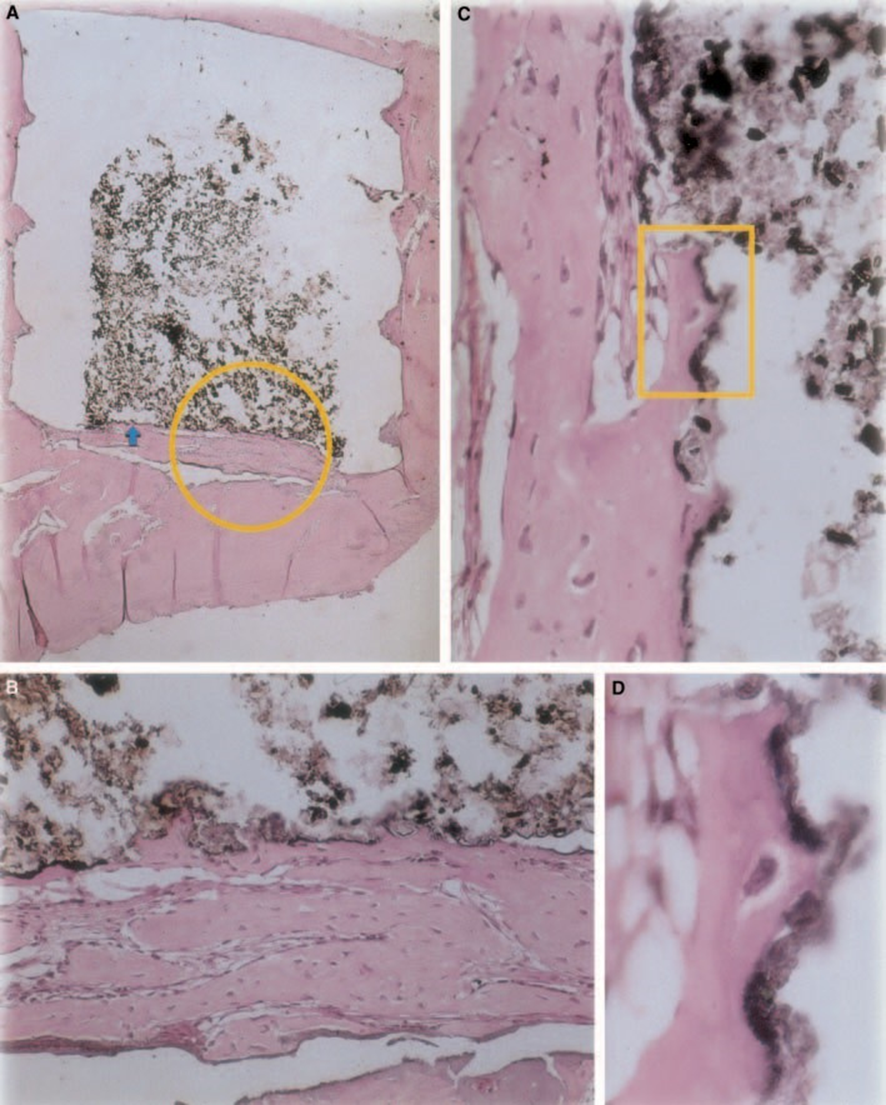

The reaction was severe with bone necrosis, resorption, mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate demonstrated by the presence of lymphocytes, macrophages and giant foreign body cells (Fig. 1C). The presence of foreign body giant cell agglomerates containing material in the cytoplasm, and necrotic tissue were common (Fig. 1D). There was greater collagen fibre deposition nearer the bone tissue than the material and low presence of inflammatory cells (Fig. 1B).

Mineral trioxide aggregate

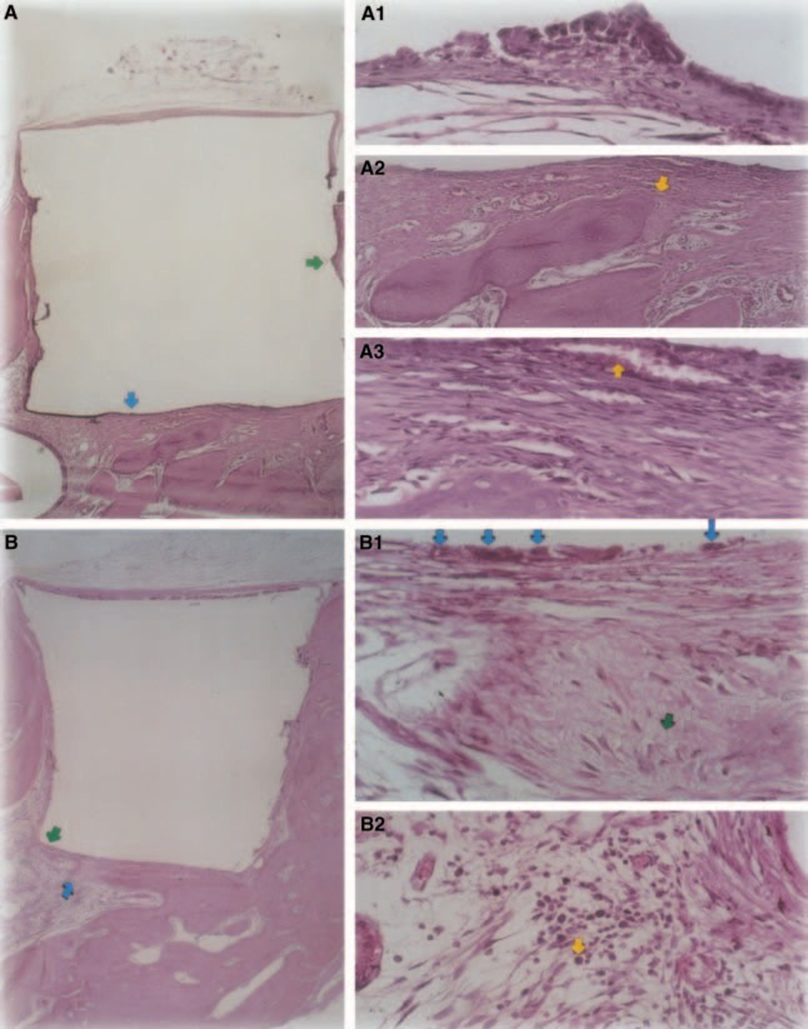

The inflammatory response was classified as none to slight. There was formation of healthy bone in close contact with the material (Fig. 3).

Z-100

Light to moderate inflammatory response was observed with dense connective tissue formation at the material/ bone tissue interface (Fig. 5A2,B1). This fibrous connective tissue was rich in fibroblasts; vessels, no inflammatory infiltrate, and mineral tissue deposition could be observed, demonstrating bone formation (Fig. 5A3). The presence of macrophages and foreign body giant cells near the material was a constant finding (Fig. 5A1,B1). Moderate chronic inflammatory infiltrate near the material was observed (Fig. 5B2).

Twelve-week observations

Negative control

The connective tissue response alongside the lateral wall outside the Teflon® cups of all specimens served as a negative control for the technique. It was possible to observe that the grooves in the outer surface of the cups were filled with new bone tissue, and a thin layer of connective tissue without inflammatory reaction could be seen between the cup and bone at all observation periods in all specimens (Fig. 6A1,A2).

Zinc oxide-eugenol

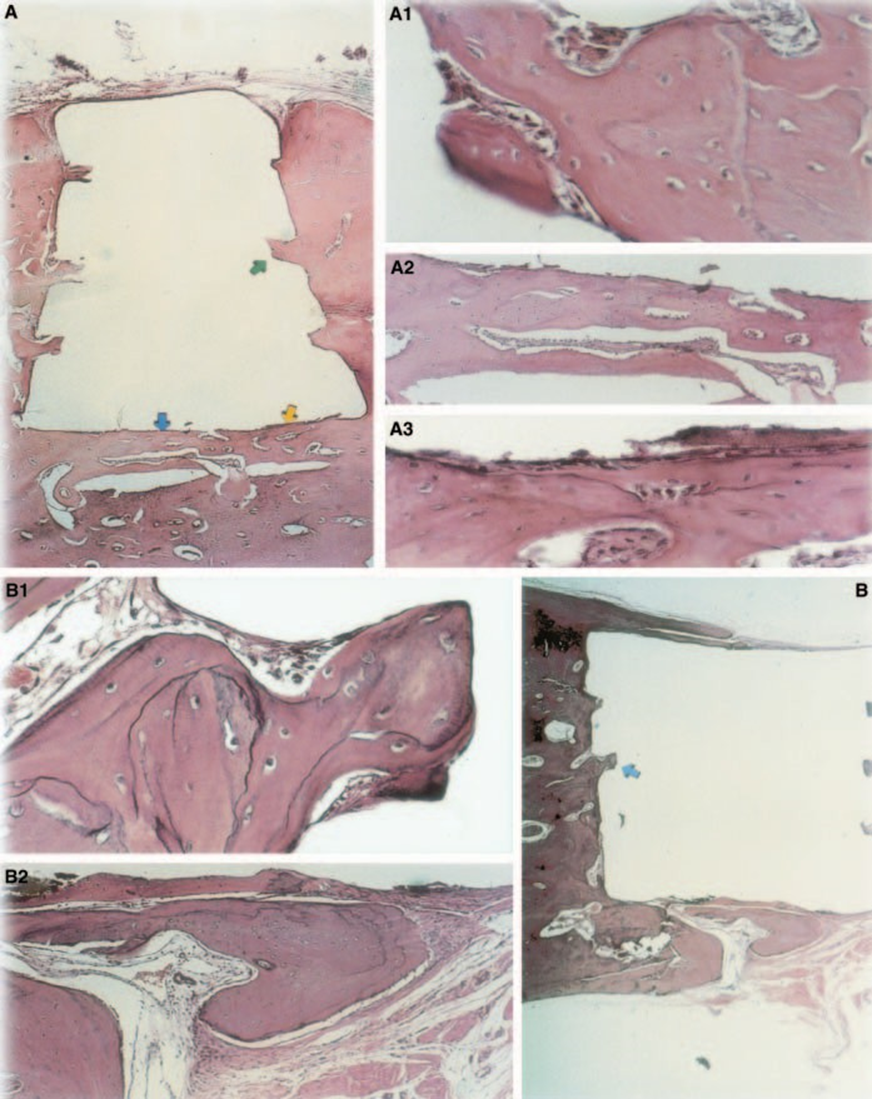

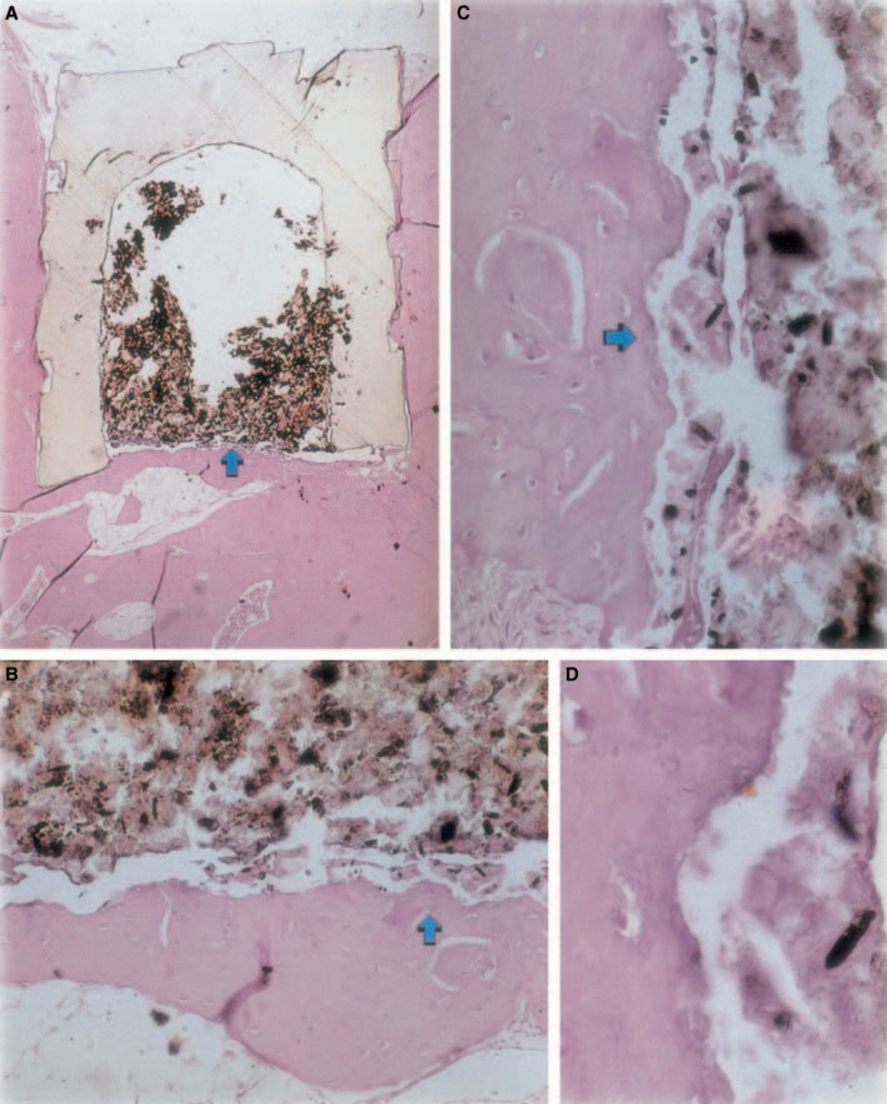

The inflammatory reaction varied from none to slight on the experimental period. There was bone formation in the interface (Fig. 2A,B). The bone around the cup was healthy and covered it completely. In some cases, there was a narrow layer of connective tissue between the implanted material and the new bone tissue (Fig. 2A1,A2,B1). There was, however, some resorption still present (Fig. 2B2).

Mineral trioxide aggregate

New bone tissue had formed at the material/tissue interface. There was no significant inflammatory reaction and when present, macrophages and giant foreign body cells were in the peripheral region, in close contact with the Teflon® cup. Healthy bone containing osteoblasts in close contact with the material was also observed (Fig. 4C).

Z-100

Connective tissue thickness was significantly decreased at the interface (Fig. 6A,B). The presence of inflammatory cells was low, except for foreign body giant cells (Fig. 6A3).

Discussion

Biocompatibility is one of the most important properties of a material used in apical root-end filling because it will be in contact permanently with living tissues in the periapical region. One of the objectives of periradicular surgery is to create a barrier between the periapical region and any physical and/or bacterial agents within the root canal system. The use of a noncompatible root-end filling material will interfere with healing in that area. Materials used in apical root-end filling, besides the necessary preliminary tests, must have their biocompatibility characteristics investigated (Torabinejad & Pitt Ford 1996).

The implant test in guinea-pig bone tissue recommended by the FDI (1980) permits the testing of the material as it is utilized in the clinical environment, prepared following the manufacturer’s recommendation. Although the results cannot be directly extrapolated to human beings, the test is standardized and allows for direct comparison between materials. The literature in this field provides results in various laboratories using the same materials to allow data to be compared (Pascon et al. 1987, Andreana et al. 1989, Pascon & Langeland 1989, Barbosa et al. 1993). The results obtained in this study confirmed the findings of others that any material placed in contact with tissues provokes a foreign body reaction (Figs 1D, 5B1 and 6A3).

The reactions along the external periphery of the Teflon® cup reflect the trauma caused by the surgical procedures necessary for the introduction of the Teflon® and its contents. Teflon® itself causes insignificant irritation in the tissues (Stanley 1985) and it was used as the carrier because of its biocompatibility (Spångberg 1969, ADA 1982). This was confirmed by the absence of inflammatory reactions on the lateral wall of the carriers at both observation periods.

The inflammatory response to ZOE was significantly greater than the other materials for both observation periods (Figs 1 and 2). This severe response to ZOE has been described in the literature (Pascon & Langeland 1989, Gulati et al. 1991, Guigand et al. 1999). It has also been demonstrated that any material that contains eugenol elicits a severe tissue reaction because of cellular respiration depression (Hume 1984). Serene et al. (1988) found that ZOE sealers activated the complement system and thus an inflammatory reaction. The prolonged inflammatory response to ZOE occurs because the reaction between the material and tissue fluids ultimately liberates eugenol from the material.

The presented results confirmed the findings reported by Torabinejad et al. (1997, 1998) concerning the inflammatory response of MTA (Figs 3 and 4). These authors tested this material in the tibias and mandibles of guinea-pigs, and as an apical root-end filling in monkeys, and reported its biocompatibility. No significant inflammatory response was observed.

Stabholz et al. (1985) introduced composite resins as apical root-end filling materials and compared their physical properties to silver amalgam, Cavit and zinc phosphate. There were not, however, any concerns about tissue response in their work. When resins were used as apical root-end materials, the results ranged from severe inflammation (Bruce et al. 1993) to a high degree of healing (Rud et al. 1991).

The results of the present study are similar to the ones of Rud et al. (1991), who suggested that composites had promising biocompatibility. Although it was a routine finding, bone growth in close contact with the Z-100 occurred, probably as a result of its low degree of toxicity (Fig. 6A2,B2).

Conclusions

- The toxicity level of the tested materials diminished with time.

- The cement based on ZOE was highly toxic during the 4-week experimental period, but this profile changed significantly after 12 weeks, when it showed biocompatible characteristics.

- All the materials studied, with the exception of ZOE, presented acceptable biocompatibility levels, within the two periods analysed.

- MTA presented excellent biological qualities with bone growth in close contact with the material and no interposing connective tissue.

- The MTA and Z-100 indicated biocompatibility in this secondary test.

Authors: C. J. A. Sousa, A. M. Loyola, M. A. Versiani, J. C. G. Biffi, R. P. Oliveira, E. A. Pascon

References

- ADA (1982) Biological Evaluation of Dental Materials. American Dental Association, New York, Document No. 41.

- Andreana S, Pascon EA, Langeland K (1989) Bone tissue response to hemofibrine [Abstract]. Journal of Dental Research 68, 381.

- Barbosa SV, Araki K, Spångberg LS (1993) Cytotoxicity of some modified root canal sealers and their leachable components. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology 75, 357–61.

- Bruce GR, McDonald NJ, Sydiskis RJ (1993) Cytotoxicity of retrofill materials. Journal of Endodontics 19, 288–92.

- FDI (1980) Recommended Standard Practices for the Biological Evaluation of Dental Materials. Federation Dentaire Internationale, London, Technical Report no. 9.

- Gartner AH, Dorn, SO (1992) Advances in endodontic surgery. Dental Clinics of North America 36, 357–78.

- Guigand M, Pellen-Mussi P, LeGolff A, Vulcain J-M, Bonnaure-Mallet M (1999) Evaluation of the cytocompatibility of three endodontic materials. Journal of Endodontics 25, 419– 23.

- Gulati N, Chandra S, Aggarwal PK, Jaiswal JN, Singh M (1991) Cytotoxicity of eugenol in sealer containing zinc-oxide. Endodontics and Dental Traumatology 7, 181–5.

- Hume WR (1984) Effect of eugenol on respiration and division on human pulp, mouse fibroblasts, and liver cells in vitro. Journal of Dental Research 63, 1262–5.

- Pascon EA, Langeland K (1989) Cytotoxicity of a new endodontic sealer [Abstract]. Journal of Dental Research 68, 244.

- Pascon EA, Spångberg L, Langeland K (1987) Cytotoxicity of endodontic sealers [Abstract]. Journal of Dental Research 66, 200.

- Pascon EA, Sousa CJA, Langeland K (2001) Biocompatibility of endodontic materials: cytotoxicity of a polyurethane resin derived from castor beam oil. Brazilian Endodontic Journal 5, 5–12.

- Rud J, Munksgaard EC, Andreasen JO, Rud V, Asmussen E (1991) Retrograde root filling with composite and a dentin-bonding agent. Part 1. Endodontics and Dental Traumatology 7, 118–25.

- Serene TP, Vesely J, Boackle RJ (1988) Complement activation as a possible in vitro indication of the inflammatory potential of endodontic materials. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology 65, 354–7.

- Spångberg L (1969) Biological effects of root-canal-filling materials. Part 7. Reaction of bony tissue to implanted root-canal-filling material in guinea pigs. Odontologisk Tidskrift 77, 133–59.

- Stabholz A, Friedman S, Abed J (1985) Marginal adaptation of retrograde fillings and its correlation with sealability. Journal of Endodontics 11, 218–23.

- Stanley HR (1985) Toxicity Testing of Dental Materials, 1st edn. Miami, FL, USA: CRC Press.

- Tassery H, Pertot WJ, Camps J, Proust JP, Déjou J (1999) Comparison of two implantation sites for testing intraosseous biocompatibility. Journal of Endodontics 25, 615–8.

- Torabinejad M, Pitt Ford TR (1996) Root-end filling materials: a review. Endodontics and Dental Traumatology 12, 161– 78.

- Torabinejad M, Pitt Ford TR, McKendry DJ, Abedi HR, Miller DA, Kariyawasam SP (1997) Histologic assessment of mineral trioxide aggregate as a root-end filling in monkeys. Journal of Endodontics 23, 225–8.

- Torabinejad M, Pitt Ford TR, Abedi, HR, Kariyawasam SP, Tang HM (1998) Tissue reaction to implanted root-end filling materials in the tibia and mandible of guinea pigs. Journal of Endodontics 24, 468–71.