3D mapping of the irrigated areas of the root canal space using micro-computed tomography

Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this study was to introduce a methodology to map irrigant spreadability within the root canal space using micro-computed tomography (micro-CT).

Materials and methods: Mandibular molars presenting Vertucci’s types I and II canal configurations were selected, and four scans using isotropic resolution of 19.5 μm were accomplished per tooth: prior to treatment (S1), after glide path (S2) and after root canal preparation (S3 and S4). A contrast solution (CS) was used to irrigate the canals at stages S2 and S4. The touched and untouched surface areas of the canals, the volume of irrigant-free areas and the percentage volume occupied by the CS were calculated. Density, surface tension and the spread pattern of the CS and 2.5 % NaOCl were also evaluated.

Results: In the type I mesial root, there was an increase in the percentage volume of free-irrigated areas from S2 to S4 preparation steps, whilst in the distal roots and type II mesial root, a decrease of irrigant-free areas was observed. The use of CS allowed the quantification of the touched surface area and the volume of the root canal occupied by the irrigating solution. Density (g/mL) and surface tension (mN/m) of the CS and 2.5 % NaOCl were 1.39 and 47.5, and 1.03 and 56.2, respectively. Besides, a similar spread pattern of the CS and 2.5 % NaOCl in a simulated root canal environment was observed.

Conclusions: This study introduced a new methodology for mapping the irrigating solution in the different stages of the root canal preparation and proved useful for in situ volumetric quantification and qualitative evaluation of irrigation spreading and irrigant-free areas.

Clinical relevance: Micro-computed tomographic technology may provide a comprehensive knowledge of the flush effectiveness by different irrigants and delivery systems in order to predict the optimal cleaning and disinfection conditions of the root canal space.

Introduction

Since the inception of the cleaning and shaping concept by Schilder, the use of instruments and chemicals has remained as the central paradigm of root canal therapy. However, particularly in root canal systems with intercanal connections, isthmuses and fins, adequate cleaning and shaping of the root canal space is a well-known difficult task. Cutting-edge advances with micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) analysis brought new perspectives on the overall mechanical preparation quality of the root canal space, confirming the inability of shaping tools in acting within the anatomical complexity of the root canal; overall, the amount of mechanically prepared root canal surface is frequently below 60 %.

These mechanical substandard results certainly compromise intracanal disinfection since pulp tissue or biofilm may remain untouched over noninstrumented dentine areas, offering the possibility for microorganisms to recolonize the canal system, leading to treatment failure. Thus, the use of an efficient irrigating protocol grabs the major role to optimize the final quality of the intracanal disinfection. In this way, considerable scientific efforts have been made to improve the overall efficiency of irrigating solutions, as well as its delivering methods, aiming to push chemicals to the hard-to-reach areas of the root canal.

During the chemomechanical preparation, spreading and flushing the irrigant throughout the canal space may be hampered by several factors, such as the unpredictable anatomical configuration of the root canal, limited irrigant exchange and volume, physico-chemical properties of the solution, intracanal gas formation and especially by the delivering technique of the solution. Using syringe irrigation, penetration of the solution will depend on the distance of the needle tip to the working length, the flow rate and the needle design. Irrigant refreshment will only happen 1 mm beyond the tip of a side-vented needle if a high flow rate is used; in contrast, when using a low flow rate, irrigant replacement in the apical third may not be sufficient.

To understand the intracanal effect of irrigants by different irrigation protocols, several experimental models have been used including histological cross sections, computational fluid dynamics (CFD), artificially created grooves and the clinical use of radiopaque solutions. However, these experimental models are limited to either providing quantitative data—like CFD—or allowing in situ evaluation—like histological models. None of them allows a 3D in situ assessment of the spreading efficacy of a given irrigant or irrigation delivery methods within the root canal space. Thus, the close-to-ideal experimental model should overcome these limitations, allowing reliable in situ volumetric quantitative evaluation of irrigation efficacy. It would also be able to track three-dimensionally whether irrigants reached defiant areas of the root canal space, mainly the ones untouched by the instruments, offering a deeper and comprehensive understanding on capabilities and limitations of different irrigation protocols. Ultimately, it would drive research towards the seeking requisite of a full microcirculation by irrigants into the anatomical complexities of the root canal system.

The aim of this methodological study sought to introduce a 3D model to trace irrigant spreadability within the root canal using a micro-CT approach. Total surface canal area and root canal volume were quantified and compared to the canal area touched by the instruments and the volume occupied by the irrigant, after different sequential trans-operative steps. The advantages of this method over the conventional approaches as well as its limitations were also carefully addressed.

Material and methods

Criterion of teeth selection

Twenty extracted human mandibular first molars with fully formed apices presenting straight roots were selected from a pool of extracted teeth, decoronated slightly above the cementoenamel junction and stored in labelled individual plastic vials containing 0.1 % thymol solution. Teeth were extracted for reasons not related to this study and initially selected based on radiographs taken in both bucco-lingual and mesio-distal directions to detect any possible root canal obstruction. In order to attain an overall outline of root canal anatomy, these teeth were pre-scanned in a low resolution (60 μm) using a micro-CT scanner (SkyScan 1174v2; Bruker microCT, Kontich, Belgium). Based on the 3D models of these pre-scan set of images, two teeth with similar lengths and presenting a type I and II Vertucci’s canal configurations system in the mesial root, respectively, and only one distal canal, were selected and scanned again at an isotropic resolution of 19.7 μm. The other teeth were kept for further use.

Root canal preparation and irrigation

The canals were negotiated to length with a size 10 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland), and the coronal thirds were flared with a size 2 LA Axxess bur (SybronEndo, Orange, CA, USA) in a low-speed contra-angle handpiece using circumferential motion. Flaring was followed by irrigation with 5 mL of 2.5 % NaOCl delivered in a syringe with a 30-gauge needle (NaviTip; Ultradent Products Inc., South Jordan, UT, USA) to the deepest penetration of the needle. Patency was confirmed by inserting a size 10 K-file through the apical foramen before and after completion of root canal preparation. Working length (WL) was established at 1 mm from canal length. Then, the apex of each root was covered with hot, flexible glue that was allowed to solidify creating a closed root canal system. This set-up allows recapitulation of canal patency but prevents fluid extrusion from the apical foramen during canal preparation.

A glide path was established by rotary NiTi preparation up to a size 20, taper 0.04 instrument (Mtwo; VDW, Munich, Germany), and canals were irrigated with 2 mL of 2.5 % NaOCl. After that, the irrigating solution was aspirated using a Capillary tip .014 (Ultradent Products Inc.) attached to a high-speed suction pump, for 1 min, with gentle up and down motion, followed by drying with absorbent paper points size 20 for 5 s each. Then, the specimen was fixed on a custom attachment within a micro-CTscanner (SkyScan 1174v2), and the root canals were immediately filled with intravascular contrast medium (Ioditrast® 76, Justesa, Mexico) using positive pressure irrigation with a 30-gauge NaviTip needle (Ultradent) to the deepest possible intracanal penetration of the needle. The extruded solution was aspirated adjacent to the coronal opening avoiding any solution to draw off the external root surface. Then, the teeth filled with the contrast solution (CS) were rescanned.

After complete aspiration of the CS, confirmed by radio- graphic examination, mesial and distal root canals were prepared using WaveOne Small and Large (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) instruments, respectively, powered by a torque-limited electric motor (VDW Silver; VDW, Munich, Germany), according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. Irrigation was performed in exactly the same manner for all specimens using 25 mL of 2.5 % sodium hypochlorite delivered in a syringe with a NaviTip 30-gauge needle (Ultradent Products Inc.) inserted at 1 mm from WL. After a new scan, the root canals were vacuum-dried and filled again with the CS, and a final scan was performed.

Micro-CT analysis

Four high-resolution scans were accomplished per tooth: prior to treatment (S1), after glide path (S2; with CS), after root canal preparation (S3; without CS) and after root canal preparation (S4; with CS). The lengths of the teeth were scanned at 50 kV, 80 μA, at an isotropic pixel size of 19.7 μm, performed by 180° rotation around the vertical axis, camera exposure time of 7,000 ms, rotation step of 0.6° and frame averaging of 2. X-rays were filtered with 500-μm aluminium filter, and a flat-field correction was taken on the day, prior to scanning to correct for variations in the pixel sensitivity of the camera. Images were reconstructed using NRecon v.1.6.3 (Bruker microCT) with a beam hardening correction of 15 %, smoothing of 2 and an attenuation coefficient range of −0.013–0.11, providing 700–900 axial cross– sections of the inner structure of each sample.

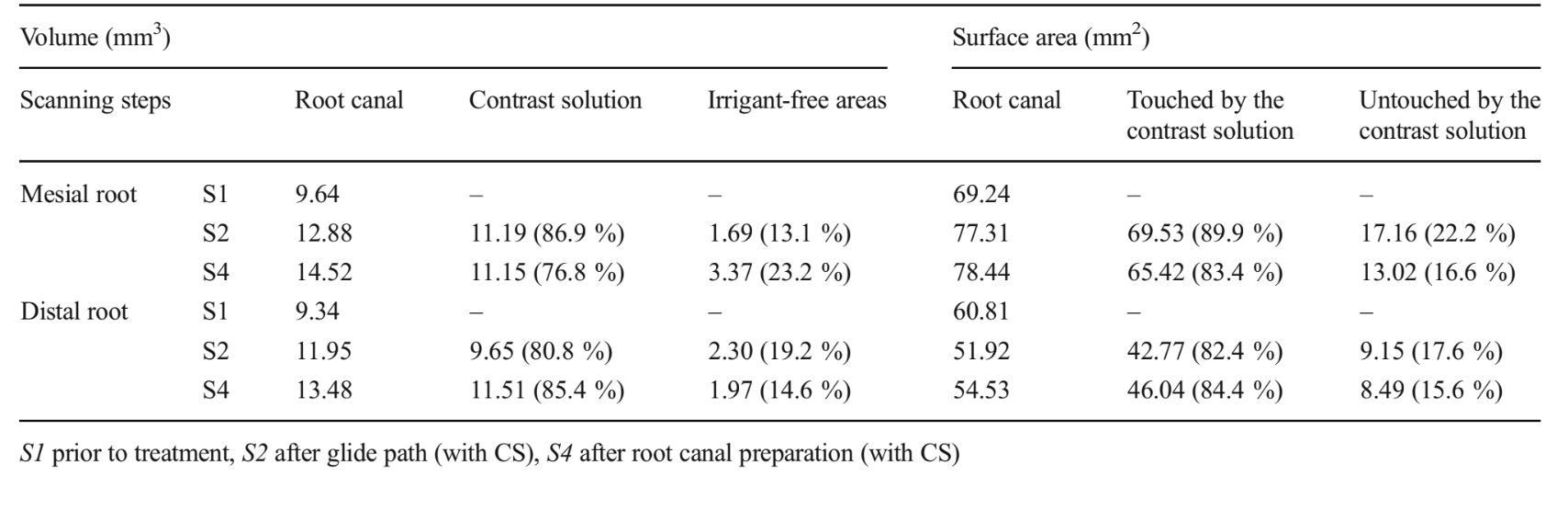

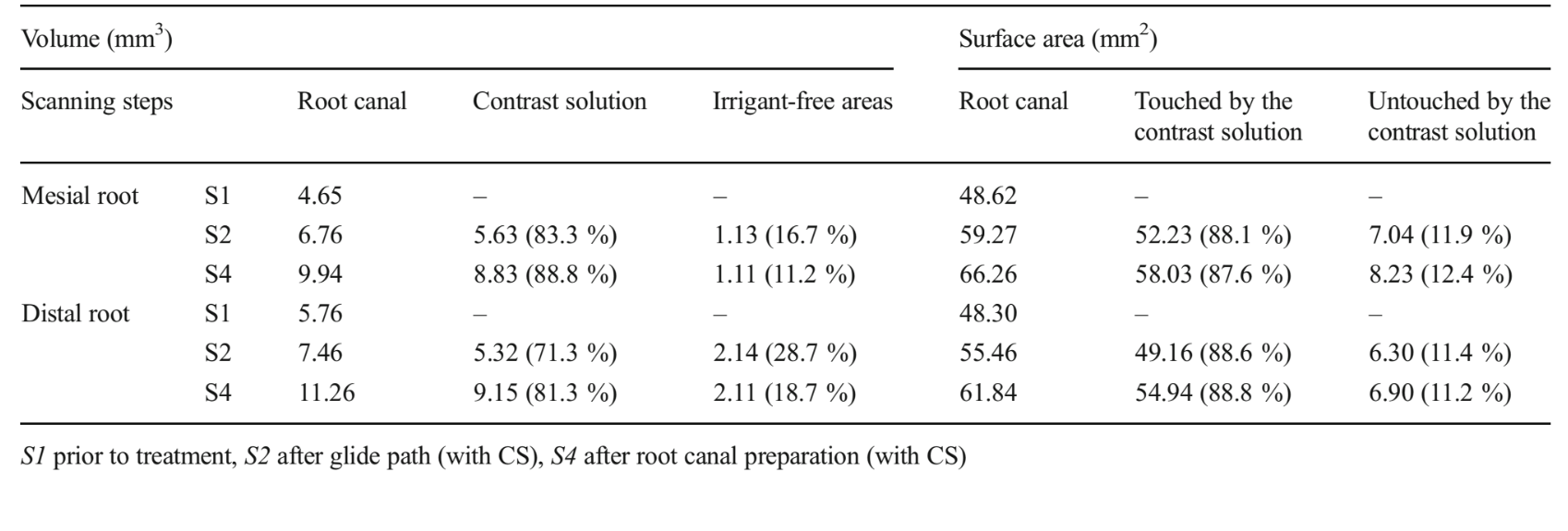

Superimposition of pre- and post-preparation datasets was ensured with PMOD software (PMOD Technologies Ltd., Zurich, Switzerland). For calculation of the parameters and surface representations of the root canal space and CS, the original greyscale images were processed with a slight Gaussian low-pass filtration for noise reduction, and an automatic segmentation threshold was used to construct polygonal surface representations of the dentine, root canal and CS, using CTAn v.1.12 software (Bruker microCT). The different contrast levels of the CS, the irrigant-free areas and the dentine yielded excellent segmentation of the specimens. Colour-coded models (green, black and blue indicate the original root canal anatomy, the CS and irrigant-free areas, respectively) enabled qualitative comparison of CS spreading pattern and the location of the irrigant-free areas during the different stages of the root canal preparation using CTVol v.2.2.1 soft- ware (Bruker microCT).

Separately and for each slice, regions of interest were chosen to allow the calculation of (a) the surface canal areas untouched by the instruments; (b) the total volume and surface area of the root canal; (c) the total volume of the CS; (d) the volume of root canal space not filled with the CS (irrigant-free areas) and (e) surface canal areas touched and untouched by the CS, using CTAn v.1.12 software (Bruker microCT). Then, DataViewer v.1.4.4 software (Bruker microCT) was used for the two-dimensional qualitative evaluation of the entrapped gas bubble areas in different levels of the root canal.

Methodological repeatability

After the final scan (S4), the root canals were vacuum-dried, and the removal of the CS was confirmed by radiographic examination. Then, the root canals were filled again with the CS using the aforementioned protocol, and a new scan using the previously described parameters was performed. This procedure was repeated five times (one scan per day on five consecutive days) for each specimen and the volume of irrigant-free areas per root canal calculated using CTAn v.1.12 software (Bruker microCT). The repeatability of the measurements was verified by measuring the interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) using MedCalc for Windows version 13.1.2.0 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium).

Validation of the CS

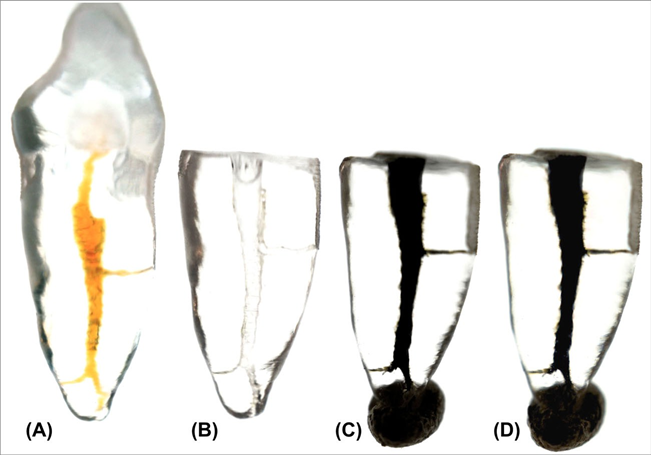

A transparent resin maxillary anterior tooth replica (TrueTooth™ #9-001; DELendo, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) was used as an in vitro intracanal standard model to qualitatively evaluate the spread of the irrigation solutions. After decoronation of the replica, preparation of the canal was performed using the aforementioned protocol for the distal roots of the mandibular molars. After that, the apical exit of the replica was closed using sticky wax. Then, the canal was irrigated with 1 mL of the CS mixed with 0.1 mL of India ink using a gauge 27 NaviTip (Ultradent Products Inc.) inserted up to 3 mm close to the apex. The filled root canal replica was set over a white lightening source and photographed using a high-resolution digital camera (Sony Nex-7; Sony, Shinagawa, Japan). After that, the canal was rinsed with 20 mL of tap water and the replica ultrasonically vibrated until no single trace of the CS mixed with India ink was seen in the root canal. After aspiration, the canal was irrigated with 1 mL of 2.5 % NaOCl mixed with 0.1 mL of India ink and immediately photographed under the same conditions. This small amount of India ink mixed with the irrigants allowed the visual evaluation of the spreadability of the solutions in a high-resolution computer screen.

Surface tension, density and the intra-canal spreading pattern were analyzed in order to certify the physico-chemical similarity between the contrast and sodium hypochlorite solutions, mixed or not with India ink.

Surface tension was measured with an automatic optical tensiometer (Dataphysics OCA20 Measuring System; Dataphysics, Filderstadt, Germany) by the so-called pendant drop shape analysis. In this method, the outer shape of a drop of liquid hanging from a syringe tip, photographed using a CCD camera, is determined from the balance of two forces. One is the effect of the force of the weight and lengthens the drop in a vertical direction, and the other works on the upper surface tension, keeping the drop in a spherical form in order to minimize the surface. Characteristic for the equilibrium is the change in the bend along the contour of the drop. This force equilibrium is described mathematically by the Young-Laplace comparison. In the present study, a detailed analysis of the drop contour and the surface tension limit was determined automatically with SCA 22 Surface and Interfacial software (Dataphysics). Density was calculated by dividing the mass per unit volume of each of the irrigant solutions.

Results

Micro-CT analysis

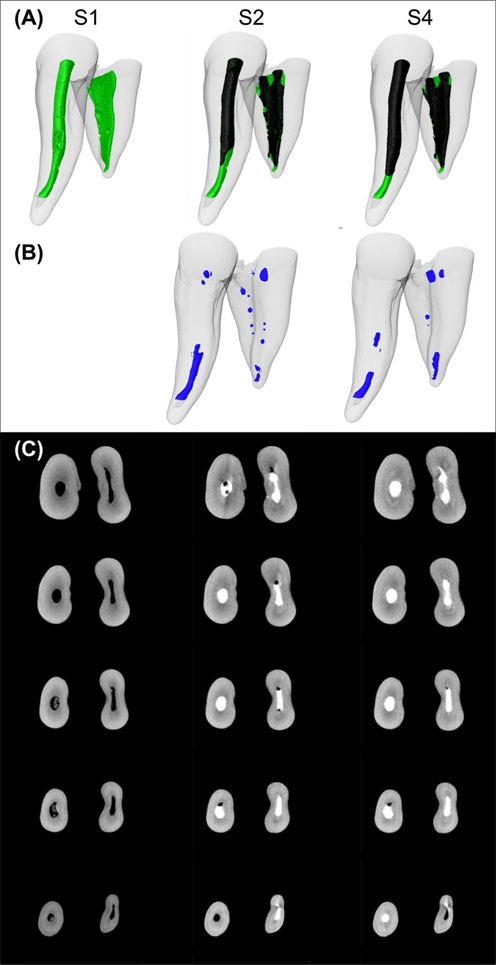

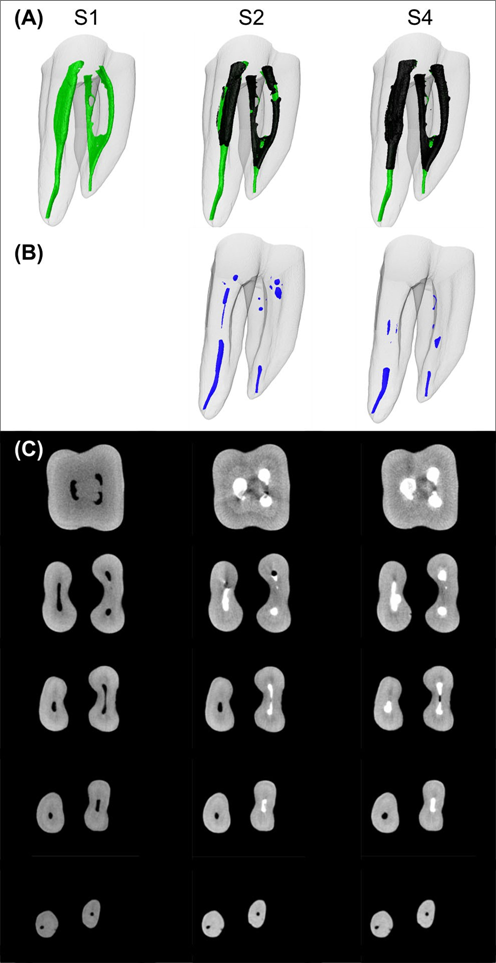

Tables 1 and 2 show the percentage volume of the root canal filled with the CS and irrigant-free areas, as well as the percentage surface areas of the root canal touched and untouched by the CS after glide path and complete root canal preparation. Evaluation of the prepared root canal without contrast (S3) showed that the percentage surface canal areas untouched by the instruments in the mesial and distal roots was 57.4 and 11.8 % in the type I molar and 35.3 and 9.5 % in the type II molar, respectively. In the type I root canal configuration molar, the surface area of the mesial canal touched by the CS diminished from 89.9 to 83.4 % after root canal preparation. Simultaneously, the percentage volume of irrigant-free areas increased from 13.1 to 23.2 %. On the other hand, in the distal roots and in the type II root canal configuration molar, the surface area of the root canal touched by the CS progressively increased followed by the volume reduction of the irrigant-free areas. Three-dimensional models of the root canals, CS and irrigant-free areas, as well as cross sections of the roots in different levels, show that root canals in both specimens were progressively filled with the CS from glide path to the entire root canal preparation together with the reduction of the irrigant-free areas (Figs. 1 and 2).

Methodological repeatability

ICC statistical analysis results showed that the degree of consistency among measurements of the volume of irrigant-free areas was very high (ICC=0.995, CI=0.981–0.999), indicating the repeatability of the method.

Validation of the CS

Images of the intracanal rinsed replicas demonstrated a similar spreading of the solutions mixed with India ink (contrast and sodium hypochlorite) in a simulated root canal environment (Fig. 3). CS showed a surface tension ranging from 47.46 to 47.53 mN/m during all the experimental procedure time, while 2.5 % NaOCl solution showed a rapid surface tension decrease, which stabilized in 56.2 mN/m after 250 s. The densities of the CS and 2.5 % NaOCl were 1.39 and 1.03 g/ mL, respectively. The amount of India ink mixed with the irrigant solutions did not affect the surface tension and density results.

Discussion

Incomplete debridement of root canal space is indeed critical for suboptimal disinfection. Ideally, efficient irrigation solutions and protocols are required to provide fluid penetrability to such an extent as to accomplishing a micro-circulation flow throughout the intricate root canal anatomy; this is the rationale used to counterbalance the suboptimal debridement quality obtained by currently available technology to mechanically enlarge the root canal space. Despite the several irrigation protocols proposed over the last decades, full and comprehensive in situ three-dimensional knowledge of the spreadability of the solution within the root canal space using different irrigation regimens is still limited. Irrigant penetrability and spreadability in the root canal space microenvironment can be mainly regarded as a result of the fluid dynamics process promoted by a given irrigation protocol. As a rule, fluid dynamics involves irrigating solution properties and features of the delivery method per se, such as velocity, pressure, density and temperature, as functions of space, time and environment. Inside the nonstandard, unpredictable and intricate root canal space, irrigating penetrability is markedly affected by fluid dynamics. Additionally, root canal space is dynamically changed by shaping procedures, which create debris capable to block the irrigant penetrability into isthmus areas, for instance. Therefore, an in situ volumetric experimental model is undoubtedly useful to provide better understanding of irrigant penetrability within the root canal space and how fluid dynamics is influenced by root canal anatomy and mechanical instrumentation.

Unfortunately, there is no well-built background on irrigant penetrability, as there is a lack of experimental models able to provide both in situ and quantitative data. Overall, the currently available in situ experimental models, such as histological methods, allow either a qualitative or a quantitative observation of the surrogate outcomes on cleaning efficacy, such as pulp tissue, dentinal debris or smear layer removal. These methodological approaches certainly are able to provide valuable information about the quality of cleaning and shaping procedures, which cannot otherwise be obtained, but they are unable to show some critical factors, such as the volume of the solution or the root canal areas effectively touched by the irrigant. Besides, the destructive approach of these methods stands for its major drawback, since the preoperative condition of the root canal is unknown.

Experimental models, which use artificial irregularities, grooves or extensions in the root canal walls, also allow in situ comparison of the presence of debris before and after irrigation. Though, the presence of debris is another surrogate outcome, which indirectly indicates irrigant efficiency. Furthermore, the inability to provide quantitative data and the huge gap between the natural real root canal space anatomy and the artificially created root canal extensions account for its intrinsic limitations. Computational fluid dynamic (CFD) models, on the other hand, provide a standard computed controlled environment, in which several parameters related to fluid dynamics can be measured and calculated. Nevertheless, it has the crucial limitation of not being an in situ model, making it unable to dynamically simulate other critical clinical factors that might influence fluid dynamics during irrigation, such as pulp tissue, dentine chips, vapour lock phenomenon and, mainly, the intricate root canal anatomy.

More recently, the use of CS to visualize the irrigating solution in the root canals using the radiographic method was introduced. Even though being able to provide an in vivo evaluation in human teeth, the use of a two-dimensional radiographic visualization prevents tracking the actual irrigant behaviour, as well as does not provide quantitative volumetric data. Plainly speaking, this means that current research is inconclusive in determining if irrigants can reach the root canal areas where shaping instruments are unable to act.

The micro-CT experimental model incepted here overcomes several limitations displayed by the aforementioned methods, as it provides direct quantitative volumetric and in situ mapping of irrigant within the root canal space. The volume of irrigation can be correlated, for instance, to the full root canal volume and per canal region as well, providing useful 2D and 3D information related to irrigation efficiency. It also allows detailed three-dimensional visualization of the hard-to-reach areas, as being possible to correlate this observation with the presence of some anatomical irregularity or the presence of dentinal debris that by chance might block the spread of the irrigant.

To date, there is currently a clear and important knowledge gap whether the area untouched by the mechanical preparation is touched by the irrigant. This information can be obtained with the proposed method, by correlating the surface area touched by the irrigant with the surface area touched and untouched by the instrument in the different steps of the root canal preparation. This way, an irrigation protocol able to spread out larger root canal areas and thus better compensates the suboptimal mechanical debridement can be noticeably identified by the current method. A comprehensive quantification of irrigant-free areas can also be calculated and correlated, for example, to the irrigant delivery method, fluid activation system, irrigation needle penetration and design, root canal configuration, amount of hard tissue debris or shaping protocols.

In the last decade, micro-CT has gained increasing significance in endodontics, as it offers a reproducible technique that can be applied quantitatively, as well as qualitatively for the three-dimensional assessment of the root canal system. In the study of different irrigation protocols, this quantitative approach may be used to increase the statistical power and reproducibility of comparative ex vivo studies; i.e. data can be further subjected to inferential statistical models to assess the relevance of different irrigation protocols following the established parameters. This interesting aspect definitely opens a new methodological appraisal to study irrigation efficiency, bringing the possibility to a better understanding of the in situ irrigant behaviour.

Despite this new methodological approach that allows for a visual assessment and quantification of the irrigant solution and irrigant-free areas using the same specimen in every step of the root canal treatment, an important limitation is that it only examines a static condition of the irrigant rather than the process of fluid dynamics during irrigation. However, this is also a limitation present in most of the previous studies as well. Another limitation of the current method is that a CS is required in order to identify and separate the solution from the hard dental tissues, as dentine. Despite the physical-chemical analysis of the CS and 2.5 % NaOCl presented similar values, they were not the same. Surface tension of the CS presented lower values compared to the 2.5 % NaOCl solution, while density was higher in the latter. Therefore, CS spreading in the root canal space may follow a different pattern compared to NaOCl. Nevertheless, the control experiment in transparent tooth replicas revealed a very similar spreading pattern for both solutions (Fig. 3) which means that this slight difference may be insignificant; i.e. the behaviour of CS is expected to be very close to the NaOCl solution. An additional concern with this methodological approach would be related to whether the calculated values and observed distribution of the contrast medium within the root canal are reproducible when using the same tooth several times. A set-up for ensuring this repeatability showed the truthfulness of the present micro-CT model regarding the distribution of irrigant-free areas within the same root canal in consecutive measurements.

This control model has no intention to drive clinical spreadability results, but rather to provide a standard intra-canal environment to visually compare the spreading of the solutions. Thus, any effect of the plastic-made root canal on wettability and solution’s spreadability is to affect similarly both solutions, which is irrelevant to the purpose of the model. Briefly, this proposed micro-CT model is able to provide in situ 3D mapping on irrigation penetrability into the root canal space; therefore, room is open to find out a similar CS to the conventional NaOCl solution than the one incepted herein.

A comprehensive knowledge of the flush effectiveness by different irrigants and delivery systems is of paramount importance to predict the optimal cleaning and disinfection conditions of the root canal space. Since the debridement quality promoted by the current available cleaning and shaping technology is largely dependent upon the chemical action of the irrigants, it lays emphasis on the necessity to pursuit more efficient irrigants and protocols to reach maximal effectiveness in irrigation. This can be obtained only by the inception of robust, quantitative and reproducible experimental models to provide comprehensive and reliable three- dimensional mapping of the irrigation-spreading pattern within the complexities of the root canal system, which raises the meaning of the current in situ experimental model.

The presented model allows a two- and three-dimensional in situ quantification of several outcome parameters related to irrigation in the complex root canal space, such as the volume of the solution and the surface area of the root canal touched and untouched by the irrigant. Moreover, as a nondestructive experimental model, it enables the correlation of these outcome parameters to several aspects that might influence irrigation penetrability, such as root canal anatomy and instrumentation-related factors, like accumulated hard-tissue debris or remaining pulp tissue, which can aid for reaching evidence-based guidelines for optimal and safe irrigation procedures.

Authors: Marco Aurélio Versiani, Gustavo De-Deus, Jorge Vera, Erick Souza, Liviu Steier, Jesus D. Pécora, Manoel D. Sousa-Neto

References:

- Schilder H (1974) Cleaning and shaping the root canal. Dent Clin N Am 18:269–296

- Ribeiro MVM, Silva-Sousa YT, Versiani MA, Lamira A, Steier L, Pécora JD, Sousa Neto MD (2013) Comparison of the cleaning efficacy of self-adjusting file and rotary systems in the apical third of oval-shaped canals. J Endod 39:398–410. doi:10.1016/j.joen. 2012.11.016

- De-Deus G, Souza EM, Barino B, Maia J, Zamolyi RQ, Reis C, Kfir A (2011) The self-adjusting file optimizes debridement quality in oval-shaped root canals. J Endod 37:701–705. doi:10.1016/j.joen. 2011.02.001

- Peters OA, Laib A, Gohring TN, Barbakow F (2001) Changes in root canal geometry after preparation assessed by high-resolution computed tomography. J Endod 27:1–6

- Versiani MA, Steier L, De-Deus G, Tassani S, Pécora JD, Sousa-Neto MD (2013) Micro-computed tomography study of oval-shaped canals prepared with the self-adjusting file, Reciproc, WaveOne, and Protaper Universal systems. J Endod 39:1060–1066. doi:10.1016/j. joen.2013.04.009

- Versiani MA, Pécora JD, Sousa-Neto MD (2011) Flat-oval root canal preparation with self-adjusting file instrument: a micro-computed tomography study. J Endod 37:1002–1007. doi:10.1016/j.joen. 2011.03.017

- Siqueira JF Jr, Alves FRF, Versiani MA, Roças IN, Almeida BM, Neves MAS, Sousa Neto MD (2013) Correlative bacteriologic and micro–computed tomographic analysis of mandibular molar mesial canals prepared by self-adjusting file, Reciproc, and Twisted File systems. J Endod 39:1044–1050. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2013.04.034

- Vera J, Siqueira JF Jr, Ricucci D, Loghin S, Fernandez N, Flores B, Cruz AG (2012) One-versus two-visit endodontic treatment of teeth with apical periodontitis: a histobacteriologic study. J Endod 38: 1040–1052. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2012.04.010

- Nair PN, Henry S, Cano V, Vera J (2005) Microbial status of apical root canal system of human mandibular first molars with primary apical periodontitis after “one-visit” endodontic treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 99:231–252

- Brito PR, Souza LC, Machado de Oliveira JC, Alves FR, De-Deus G, Lopes HP, Siqueira JF Jr (2009) Comparison of the effectiveness of three irrigation techniques in reducing intracanal Enterococcus faecalis populations: an in vitro study. J Endod 35:1422–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.07.001

- Gu LS, Kim JR, Ling J, Choi KK, Pashley DH, Tay FR (2009) Review of contemporary irrigant agitation techniques and devices. J Endod 35:791–804. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2009.03.010

- Gulabivala K, Patel B, Evans G, Ng YL (2005) Effects of mechanical and chemical procedures on root canal surfaces. Endod Topics 10: 103–122

- Zehnder M (2006) Root canal irrigants. J Endod 32:389–398. doi:10. 1016/j.joen.2005.09.014

- Boutsioukis C, Verhaagen B, Versluis M, Kastrinakis E, Wesselink PR, van der Sluis LW (2010) Evaluation of irrigant flow in the root canal using different needle types by an unsteady computational fluid dynamics model. J Endod 36:875–879. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2009.12. 026

- Boutsioukis C, Lambrianidis T, Kastrinakis E (2009) Irrigant flow within a prepared root canal using various flow rates: a computational fluid dynamics study. Int Endod J 42:144–155. doi:10.1111/j.1365- 2591.2008.01503.x

- Vera J, Hernandez EM, Romero M, Arias A, van der Sluis LW (2012) Effect of maintaining apical patency on irrigant penetration into the apical two millimeters of large root canals: an in vivo study. J Endod 38:1340–1343. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2012.06.005

- Nadalin MR, Perez DE, Vansan LP, Paschoala C, Sousa-Neto MD, Saquy PC (2009) Effectiveness of different final irrigation protocols in removing debris in flattened root canals. Braz Dent J 20:211–214. doi: S0103-64402009000300007

- Gao Y, Haapasalo M, Shen Y, Wu H, Li B, Ruse ND, Zhou X (2009) Development and validation of a three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics model of root canal irrigation. J Endod 35:1282– 1287. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2009.06.018

- van der Sluis LW, Gambarini G, Wu MK, Wesselink PR (2006) The influence of volume, type of irrigant and flushing method on removing artificially placed dentine debris from the apical root canal during passive ultrasonic irrigation. Int Endod J 39:472–476. doi:10.1111/j. 1365-2591.2006.01108.x

- Vera J, Arias A, Romero M (2012) Dynamic movement of intracanal gas bubbles during cleaning and shaping procedures: the effect of maintaining apical patency on their presence in the middle and cervical thirds of human root canals-an in vivo study. J Endod 38: 200–203. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2011.10.026

- Vera J, Arias A, Romero M (2011) Effect of maintaining apical patency on irrigant penetration into the apical third of root canals when using passive ultrasonic irrigation: an in vivo study. J Endod 37:1276–1278. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2011.05.042

- Vertucci FJ (1984) Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 58:589–599

- Paqué F, Laib A, Gautschi H, Zehnder M (2009) Hard-tissue debris accumulation analysis by high-resolution computed tomography scans. J Endod 35:1044–1047. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2009.04.026