Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Enhance Physicochemical Characteristics of Grossman Sealer

Abstract

Introduction: Metallic antibacterial nanoparticles have been shown to provide distinct antibacterial advantage and antibiofilm efficacy when applied in infected root canals. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the influence of incorporating zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-Np) on the physicochemical properties of Grossman sealer.

Methods: Grossman sealer was prepared according to its original formula. Additionally, 4 experimental sealers were prepared by replacing the zinc oxide component of the powder with ZnO-Np (average size of 20 nm) in different amounts (25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%). Characterization of the setting time, flow, solubility, dimensional changes, and radiopacity were performed according to American National Standards Institute (ANSI)/American Dental Association (ADA) Specification 57. Scanning electron microscopic and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopic analyses were conducted to assess the ultrastructural and chemical characteristics of experimental sealers subjected to the solubility test. Statistical analyses were performed with analysis of variance and post hoc Tukey-Kramer tests with a significance level of 5%.

Results: A statistically significant difference in the setting time was observed among groups (P < .05), but only 25% ZnO-Np sealer complied with ANSI/ADA requirements. There was a significant difference in the flow characteristics between the control and 25% and 75% ZnO-Np experimental sealers (P < .05), but all sealers conformed to ANSI/ADA standardization; 25% ZnO-Np sealer showed significantly less solubility (1.81% 0.31%) and dimensional change (—0.34% 0.12%) than other sealers (P < .05). All sealers showed ultrastructural changes with increasing solubility.

Conclusions: ZnO-Np decreased the setting time and dimensional changes characteristic of Grossman sealer; 25% ZnO-Np improved the physicochemical properties of Grossman sealer in accordance with ANSI/ADA requirements. (J Endod 2016;■:1–7)

The root canal sealer performs several functions during root canal obturation, including filling the spaces between the core filling material and the canal wall as well as filling root canal irregularities such as apical ramifications and deltas. Over the last 8 decades, gutta-percha and zinc oxide (ZnO)-eugenol–based sealers have been the most widely used filling material in endodontics. ZnO-containing sealer was introduced by Rickert and Dixon and later improved by Grossman; however, in both formulations, precipitated silver used for radiopacity produced sulfides, which caused tooth discoloration. Thus, silver was eliminated from the composition, whereas zinc chloride was substituted with almond oil to avoid tooth discoloration and at the same time increase setting time. Later, anhydrous sodium tetraborate was added to the powder, and almond oil was removed from the eugenol because the addition of the former improved the working time of the sealer. Previous studies have examined the role of different constituents on the physical characteristics of Grossman sealer; however, despite the popularity of ZnO-containing sealers, very few improvements have been made in its composition until a few years ago.

Nanoparticles (Np) are ultrafine particles of insoluble constituents with a diameter less than 100 nm. In the last decade, they have opened new possibilities and significant interest in health care, mainly because of their distinct chemical, biological, and broad-spectrum antibacterial characteristics. Recently, nanoparticles of ZnO (ZnO-Np) and/or chitosan were added to the original composition of ZnO-containing sealers. This modification inhibited biofilm formation within the sealer-dentin interface, reduced cytotoxicity, and improved sealing ability and antibacterial properties of the ZnO-based sealer. Although antibacterial activity, sealability, and cytotoxicity may be desirable, root canal sealers must possess several physical characteristics for optimal functioning as a root canal sealer. Thus, the aim of this in vitro study was to evaluate the effect of incorporating different degrees of ZnO Np on the setting time, flow, solubility, dimensional changes, and radiopacity properties of Grossman sealer. The ultrastructural and chemical characteristics of the experimental sealers during solubility were also analyzed. This study will aid in determining the optimal levels of ZnO-Np required for the ideal functioning of improved Grossman sealer.

Materials and Methods

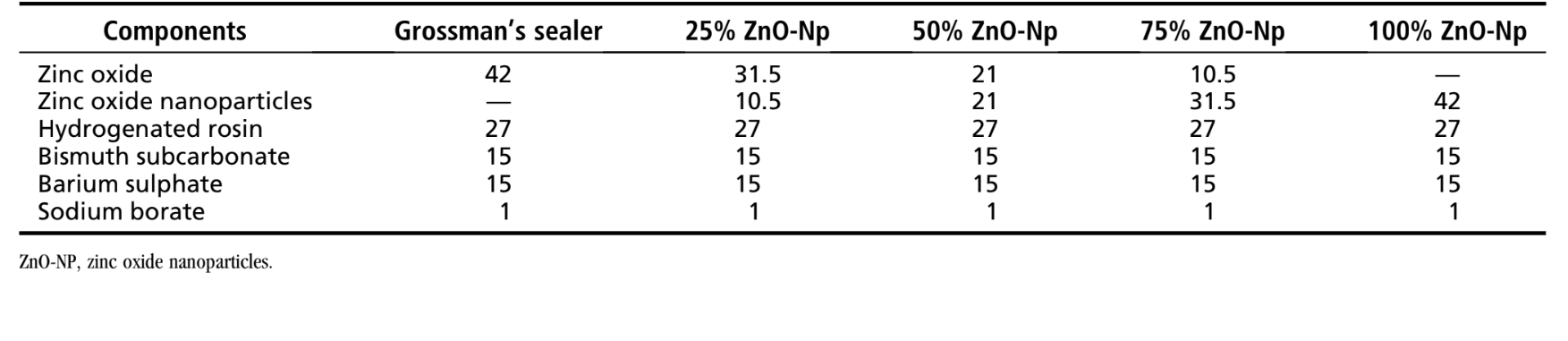

The composition of the ZnO sealer used as a control in this study followed the original instructions to prepare Grossman sealer, which contains ZnO (42%), hydrogenated resin (27%), bismuth subcarbonate (15%), anhydrous sodium tetraborate (1%) as powder, and eugenol as liquid. Additionally, 4 experimental root canal sealers were prepared by replacing the ZnO component of the powder with ZnO-Np (Nanostructured & Amorphous Materials, Inc, Houston, TX) in different percentage amounts (25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%) (Table 1). All ZnO-Np used in this study were of analytical grade (99.5% purity, spherical particles with an average size of 20 nm, specific surface area ≥40 m2/g, bulk density of 0.1–0.2 g/cm3, pH value of 6.5–7.5).

The powder/liquid ratio and spatulation time for the sealers were established according to Sousa Neto et al. The appropriate smooth and creamy consistency was standardized when the suspended mix clung to the inverted spatula blade for 10–15 seconds before dropping from the spatula. Therefore, for a mean spatulation time of 120 seconds, a mean of 1.1 g powder for 0.20 mL eugenol was used. A single operator characterized the physicochemical properties, whereas another examiner who was blinded to the experimental materials performed the analysis of the results. All tests were performed at 23° ± 2°C and 50% ± 5% relative humidity inside a cabinet containing a heater (800-Heater; PlasLabs, Lasing, MI), and the materials were exposed to the experimental conditions 48 hours before the beginning of procedures. The mean of 5 replicates for each sealer was recorded to determine the setting time, flow, dimensional change, and radiopacity.

Setting Time

The external border of a plaster of paris ring (internal diameter = 10 mm, height = 2 mm) was secured with wax on a glass plate, filled with the sealer, and transferred to a chamber (37°C, 95% relative humidity). The setting time was recorded after 150 ± 10 seconds from the start of mixing with a Gilmore-type needle (mass of 100 ± 0.5 g) having a flat end (cross-sectional diameter of 2.0 ± 0.1 mm), which was carefully lowered vertically onto the horizontal surface of the sealer. The needle tip was cleaned, and the probing was repeated until indentations ceased to be discernible. If the results differed by more than 5%, the test was repeated.

Flow

A total of 0.5 mL of the sealer was placed on a glass plate (10 × 10 × 3 mm) using a graduated disposable 3-mL syringe. At 180 ± 5 seconds after the onset of mixing, another plate (mass of 20 ± 2 g) and a load of 100 N were applied centrally on top of the material. Ten minutes after the commencement of mixing, the load was removed, and the average of the major and minor diameters of the compressed discs was calculated using a digital caliper with a resolution of 0.01 mm (Mitutoyo MTI Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). If the major and minor diameters of the discs were uniformly circular and both measurements were consistent to be within 1 mm, the results were recorded.

Solubility

Twenty 1.5-mm-thick cylindrical Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene; DuPont, Knivsta, Sweden) molds (internal diameter = 7.75 mm) supported by a glass plate were filled with freshly mixed sealer. After partially embedding an impermeable nylon thread (3 cm in length) into the sealer, another glass plate was positioned on the mold, and the assemblies were transferred to a chamber (37°C, 95% relative humidity) for a period corresponding to 3 times the sealer setting time. After this period, 10 samples from each group were removed from the mold, weighed, placed in pairs, and suspended by the nylon thread inside a plastic vessel containing 7.5 mL ultrapure deionized water (MilliQ; Millipore, Billerica, MA) for 7 days (37°C, 95% relative humidity). The samples were then removed from the containers, rinsed with deionized water, blotted dry with absorbent paper, and placed in a dehumidifier for 24 hours before weighing them again. The weight loss of each sample, expressed as a percentage of the original mass (m% = mi — mf), was taken as the solubility of the test material.

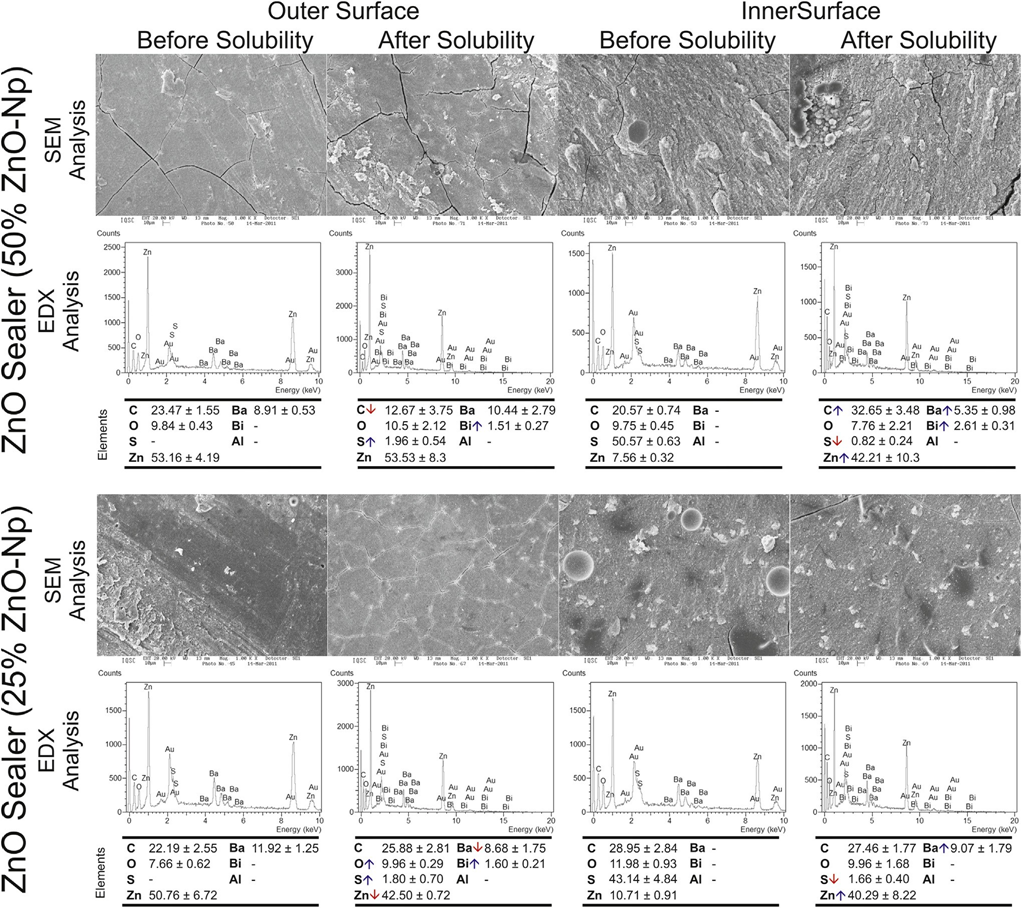

Scanning Electron Microscopic/Energy-dispersive X-ray Analysis

Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopic analyses were performed on 10 samples submitted to the solubility test, and 10 samples prepared during this experimental step, but not exposed to deionized water, were analyzed. Each sample was sectioned into halves, fixed on a metallic stub, and sputter coated with gold palladium (Bal-Tec AG, Balzers, Germany) at 20 mA. A scanning electron microscope (Zeiss LEO 440; LEO Electron Microscopy LTD, Cambridge, UK) equipped with an EDX system (Isis System Series 200; Link Analytical, Lidingö, Sweden) was used for imaging and to determine the elemental composition at the outer and inner surfaces of the sealers at 5 random regions of interest (analytic area = 0.01 mm2). The results were recorded based on their average.

Dimensional Change

A 3.58-mm-high cylindrical Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene, Du-Pont) mold measuring 3 mm in diameter was placed on a glass plate and filled with a freshly mixed sealer. Then, a glass coverslip was pressed onto the upper surface of the mold, and the assembled unit was kept firmly bound with a C-shaped clamp for a period corresponding to 3 times the sealer setting time (37°C, 95% relative humidity). Subsequently, the flat ends of the mold were ground with 600-grit wet sandpaper, the sample was removed from the mold, measured with a digital caliper, and stored individually in a 50-mL vessel containing 2.24 mL deionized distilled water for 30 days (37°C, 95% relative humidity). Each sample was later removed from the container, blotted dry with absorbent paper, and measured again for length. The percentage of the dimensional alterations was calculated by using the following formula: ([L30 — Li]/Li)*100, where Li and L30 are the length of the sample before and after 30 days of storage, respectively.

Radiopacity

An acrylic plate containing 4 wells (1-mm depth and 5-mm diameter) was placed over a glass plate, and freshly mixed sealers were carefully introduced into the wells using a syringe. Then, another glass plate was placed on top of the well for a period corresponding to 3 times the setting time (37°C, 95% relative humidity). The acrylic plate was later positioned alongside with an aluminum step wedge (Margraf Dental MFG Inc, Jenkintown, PA), and a digital radiograph was acquired (Digora System; Soredex Orion Corporation, Helsinki, Finland) at 70 kVp and 8 mA (object-to-focus distance = 30 cm; exposure time = 0.2 seconds). The exposed imaging plate of the sample was scanned (Digora Scanner) and analyzed for radiopacity. The average of the gray levels in a standardized region of interest for each sealer, described by the function ‘‘density mean,’’ was determined using software Digora v.5.1 for Windows (Digora System).

Statistical Analysis

Because the results showed normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test) and homoscedasticity (Levene test), 1-way analysis of variance and post hoc Tukey-Kramer tests were used for comparison between groups, with a significance level set at 5% (SPSS 17.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

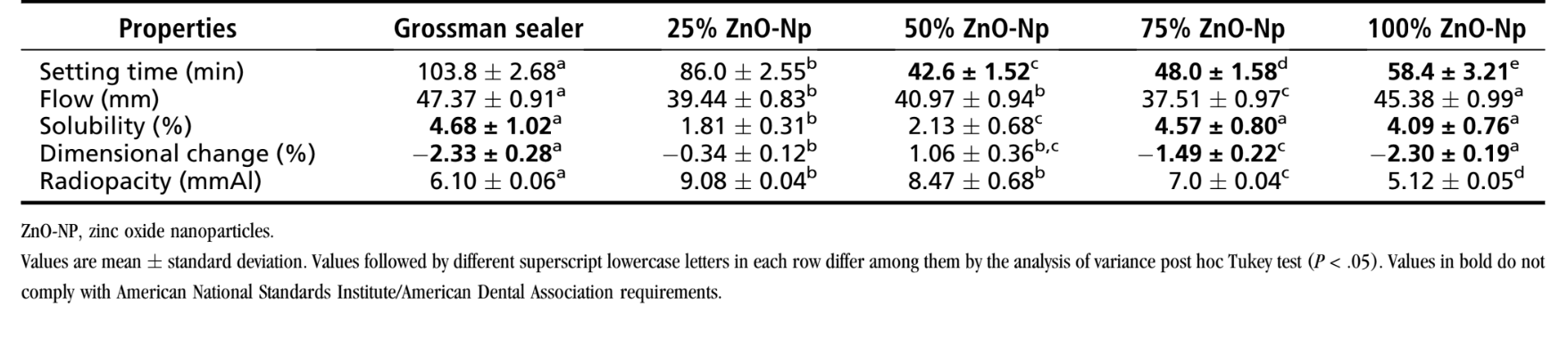

The results of the physicochemical tests of Grossman sealer and the experimental ZnO-Np–based sealers are summarized in Table 2.

Setting Time

A statistically significant difference of the setting time was observed among groups (P < .05). The setting time of 25% ZnO-Np sealer (86.0 ± 2.55 minutes) was the only experimental material that complied with American National Standards Institute (ANSI)/American Dental Association (ADA) requirements. Increasing the amount of ZnO-Np to 50%, 75%, or 100% decreased the mean setting time of the sealer.

Flow

All sealers conformed to ANSI/ADA standardization. Overall, there was no significant difference among the control and ZnO-Np– based experimental sealers (P > .05); however, mixing 25%–75% ZnO-Np with the sealer significantly reduced the flow characteristics (P < .05).

Solubility

Solubility values of Grossman (4.68 % 1.02%), 75% ZnO-Np (4.57% 0.80%), and 100% ZnO-Np (4.09% 0.76%) sealers showed no statistical difference (P > .05) and were higher than ANSI/ADA requirements. Only 25% and 50% ZnO-Np sealers conformed to ANSI/ADA standardization, but 25% ZnO-Np sealer showed significantly less solubility (1.81% 0.31%) than the other tested sealers (P < .05).

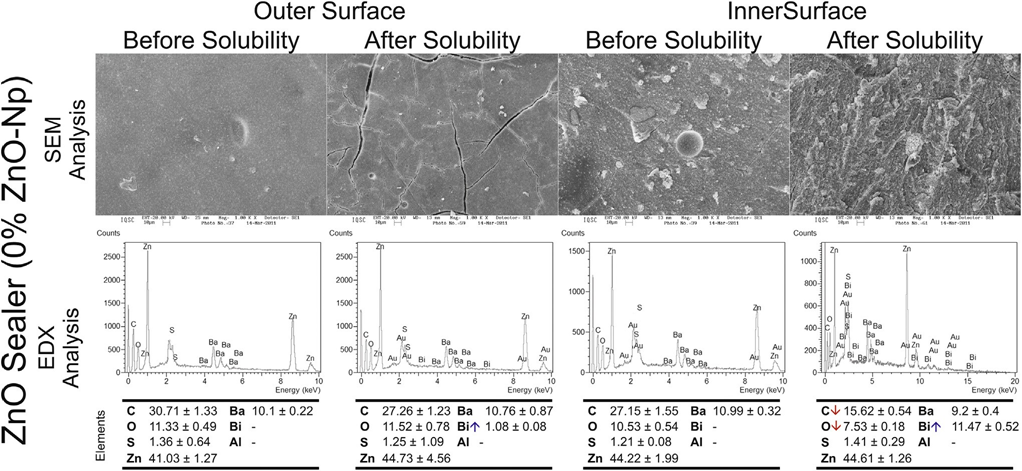

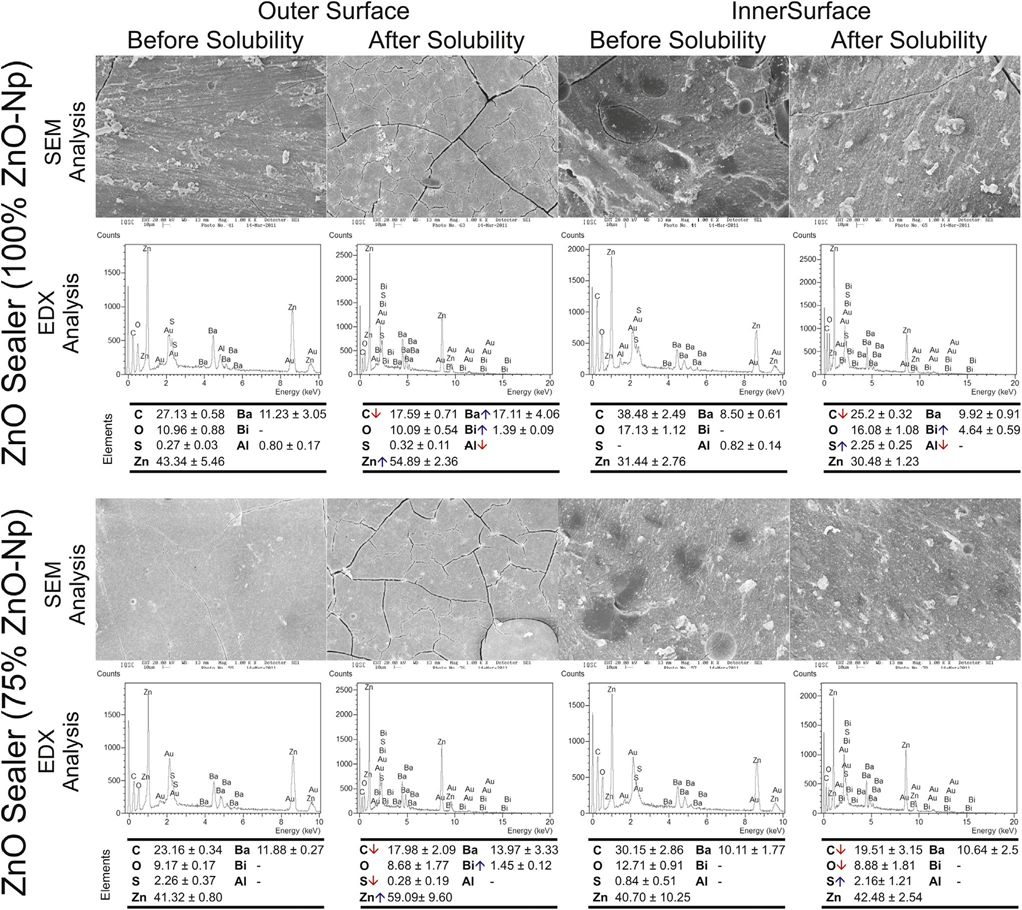

SEM/EDX Analysis

Typical SEM micrographs and corresponding EDX spectra of elements obtained from the samples before and after water storage in the solubility test are shown in Figures 1–3. Overall, it was noted that all the surfaces presented morphological changes after the solubility test. Energy-dispersive X-ray analysis of the outer and inner surfaces of all the sealers displayed Zn, Ba, C, O, S, and Bi peaks in a decreasing order.

SEM analysis of Grossman sealer (Fig. 1) and experimental 50%–100% ZnO-Np sealers (Fig. 2) showed a compact outer surface before the solubility test, with the appearance of cracks and small porosities after exposure to water. Analysis of the inner surface revealed irregular structures with particles of different dimensions and shapes that decrease in number after the solubility test. The loss of the matrix was evident, and the filler particles (granular material) were more distinguishable. Overall, in these sealers, EDX showed an increase of Bi and a significant reduction in C values after the test.

surfaces of the control group (Grossman sealer) before and after the solubility test. The down and up arrows in the energy-dispersive X-ray analysis mean decreasing and increasing in the average of elemental constitution after the solubility test, respectively.

The outer and inner aspects of 25% ZnO-Np sealer (Fig. 3), before and after the solubility test, were compact and mostly homogeneous rough surfaces. Cracking was not observed in the outer surface before or after the test. In the inner surface of the specimens, a nonhomogeneously dispersion of irregular-shaped particles was observed. A few small cracks could be also observed after the solubility test, but they may have been caused by the sectioning procedure. In the outer surface, energy- dispersive X-ray analysis showed a reduction of Zn and Ba and increased O, Bi, and S values, whereas in the inner surface there were an increase in Ba and Zn and a decrease in S values. No changes in C value were detected after the solubility test in either the outer or inner surfaces.

surfaces of the control and experimental sealers with 50% and 25% of zinc oxide nanoparticles before and after the solubility test. The down and up arrows in the

energy-dispersive X-ray analysis mean decreasing and increasing in the average of elemental constitution after the solubility test, respectively.

Dimensional Change

All materials exhibited postsetting shrinkage (negative values), and the dimensional changes of Grossman (—2.33% ± 0.28%), 75% ZnO-Np (—1.49% ± 0.22%), and 100% ZnO-Np (—2.30% ± 0.19%) sealers did not conform to ANSI/ADA requirements.

The lowest mean dimensional change was observed in 25% ZnO-Np sealer (—0.34% ± 0.12%).

Radiopacity

All sealers showed radiopacity above 3 mm aluminum as recommended by ANSI/ADA. The radiopacity values of 25% ZnO-Np (9.08 ± 0.04 mmAl) and 50% ZnO-Np (8.47 ± 0.68 mmAl) sealers were statistically similar (P > .05) but higher than the other groups (P < .05).

Discussion

Setting time is the time necessary for the sealer to achieve its definitive properties. It depends on the constituents, particle size, ambient temperature, and relative humidity. There is no stipulated standard setting time for sealers, but clinical advantage demands that it must be long enough to allow the placement and adjustment of core root filling when necessary. According to the manufacturer, Grossman sealer hardens in approximately 2 hours at 37°C and 100% relative humidity; however, the precise setting time is dependent on the quality of the ZnO, pH of the resin, manipulation technique, consistency, degree of humidity, and temperature/ dryness of the mixing slab/spatula. The observed decrease in the setting time of the experimental sealers in this study may be attributed to the increased rate of hydration reaction in the sealers prepared with ZnO-Np.

The ability of an endodontic sealer to flow into the noninstrumented portions of the root canals and between the gutta-percha–root dentin interface, without increasing the risk of periapical extrusion, is an important characteristic, which is influenced by the particle size, rate of shear, temperature, time, internal diameter of canals, and rate of insertion. The ANSI/ADA standards require that a sealer should have a diameter of no less than 20 mm, and the tested Np-containing sealers in this study conformed to this requirement. The enhanced flow properties in the Np-incorporated sealers could be explained by the ability of ZnO-Np to disrupt the bulk cohesion and reduce the frictional forces between large particles more effectively.

Solubility indicates the loss of material mass when immersed in water. Ideally, it should not exceed 3%. In the current study, a modified solubility test that allowed testing of a smaller volume of samples was used. The high solubility of Grossman sealer (4.68% ± 1.02%) observed may be caused by the continuous release of free eugenol, which is slightly hydrosoluble and present in the set ZnO sealer. The continuous leaching out of eugenol by water would result in the progressive decomposition of zinc eugenolate and disintegration of sealer. Besides, the addition of anhydrous sodium borate, which is highly soluble in water, combined with the disintegration of rosin during the hydrogenation process favors detachment of particles from the material and an increase in porous structure, leading to an increased dissolution rate, which helps to explain the results. Interestingly, the addition of 25% or 50% of ZnO-Np to the sealer formulation significantly reduced the solubility in a level that complies with ANSI/ADA requirements. These findings are caused by the high reactivity of Nps, which makes the cement micro-structure denser and reduces porosity.

Dimensional stability is an important property for endodontic sealers. Shrinkage of sealers over time may create gaps in its interface, leading to the loss of marginal adaptation and bacterial leakage, which, in turn, may compromise the outcome of the root canal treatment. According to ANSI/ADA standards, the dimensional change of a sealer after setting should not exceed 1% shrinkage or 0.1% expansion. In this study, all sealers had some degree of postsetting shrinkage, which is in accordance with previous studies. Grossman, 75% ZnO-Np, and 100% ZnO-Np sealers had the highest dimensional change results, which can be explained by their high solubility values. As mentioned earlier, the degree of degradation of ZnO-eugenol–based sealers observed during the solubility test exceeds the degree of water absorption after setting because of the leaching out of excess and non-reacted eugenol as well as the hydrolysis of set zinc eugenolate, which may affect the dimensional stability. On the other hand, the ANSI/ ADA requirement for dimensional changes after setting complied with the addition of 25% of ZnO-Np in the powder. As highlighted in previous studies, an effective size and uniform distribution of ZnO-Np may reduce the hygroscopicity of the sealer, improving its dimensional stability.

The relative radiopacity of root filling materials is essential for the control of placement. Although the standards require only a lower limit to this property, it should be realized that extreme contrast in a material may lead to a false impression of a dense and homogenous fill. In the present study, ANSI/ADA requirements were fulfilled in all tested sealers. The high values of radiopacity observed in the ZnO-eugenol–based sealers have been explained by the presence of 3 components, bismuth subcarbonate, barium sulphate, and ZnO. It is interesting to notice that the addition of 25%–50% of ZnO-Np significantly increased the radiopacity characteristics of the experimental ZnO-Np sealers, as reported in a recent study.

In the present study, the replacement of 25% of the conventional ZnO powder by ZnO-Np improved the setting time, flow, solubility, dimensional stability, and radiopacity of Grossman sealer in adherence to ANSI/ADA requirements. Considering that the physicochemical properties of the endodontic sealers are mostly determined by the type and proportions of their main components, it may be hypothesized that the combination of 25% of ZnO-Np with 75% of conventional ZnO allowed a better stabilization of the crystalline matrix of the sealer.

Actually, the evidence to support this statement is based on the slight loss of components of the sealer during the solubility test, mostly the carbon element, and the organic component from the hydrogenated rosin. In Grossman sealer, the hydrogenated rosin contributes to increased flow and decreased solubility. Rosin is a solid form of resin obtained from pines and some other plants. It consists of a complex mixture of different substances including organic acids such as plicatic acid, pimaric acid, and, in special cases, abietic acid (C20H30O2), which are obtained from the hydrogenation of rosin. Although nanosized materials can be useful in endodontics, they may also be potentially dangerous once they have unrestricted access to the host tissue because they may evade the host immune system. Thus, further safety studies on the incorporation of ZnO-Np to root canal sealer must be conducted before its clinical application.

Overall, ZnO-Np incorporation decreased the setting time and dimensional changes characteristic of Grossman sealer. The replacement of 25% of conventional ZnO powder with ZnO-Np improved the setting time, flow, solubility, dimensional stability, and radiopacity of Grossman sealer, which were all in adherence to ANSI/ADA requirements.

Authors: Marco Aurélio Versiani, Fuad Jacob Abi Rached-Junior, Anil Kishen, Jesus Djalma Pécora, Yara Terezinha Silva-Sousa, Manoel Damião de Sousa-Neto

References

- Suresh Chandra B, Gopikrishna V. Grossman’s Endodontic Practice, 13th ed. Haryana, India: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2014.

- Ørstavik D. Materials used for root canal obturation: technical, biological and clinical testing. Endod Topics 2005;12:25–38.

- Rickert U, Dixon CM. The controlling of root surgery. In: Transactions of the 8th International Dental Congress, Section 111a. Paris, France: FDI World Dental Federation; 1931:15–22.

- Grossman LI. Filling root canals with silver points. Dent Cosmos 1936;78:679–87.

- Grossman LI. An improved root canal cement. J Am Dent Assoc 1958;56:381–5.

- Grossman LI. Algunas observaciones sobre obturaci´on de conductos radiculares. Rev Asoc Odont Argent 1962;50:61–6.

- Grossman LI. Endodontic Practice, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1974.

- Grossman LI. Physical properties of root canal cements. J Endod 1976;2:166–75.

- Sousa-Neto MD, Guimarães LF, Saquy PC, Pécora JD. Effect of different grades of gum rosins and hydrogenated resins on the solubility, disintegration, and dimensional alterations of Grossman cement. J Endod 1999;25:477–80.

- DaSilva L, Finer Y, Friedman S, et al. Biofilm formation within the interface of bovine root dentin treated with conjugated chitosan and sealer containing chitosan nano-particles. J Endod 2013;39:249–53.

- Javidi M, Zarei M, Omidi S, et al. Cytotoxicity of a new nano zinc-oxide eugenol sealer on murine fibroblasts. Iran Endod J 2015;10:231–5.

- Javidi M, Zarei M, Naghavi N, et al. Zinc oxide nano-particles as sealer in endodontics and its sealing ability. Contemp Clin Dent 2014;5:20–4.

- Kishen A, Shi Z, Shrestha A, Neoh KG. An investigation on the antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy of cationic nanoparticulates for root canal disinfection. J Endod 2008;34:1515–20.

- Kishen A. Nanotechnology in Endodontics: Current and Potential Clinical Applications, 1st ed. Switzerland: Springer; 2015.

- Sousa Neto MD, Guimarães LF, Gariba Silva R, et al. The influence of different grades of rosins and hydrogenated resins on the powder-liquid ratio of Grossman cements. Braz Dent J 1998;9:11–8.

- American National Standards Institute/American Dental Association. Specification No. 57–57 Endodontic Sealing Material. Chicago, IL; 2000.

- Carvalho-Júnior JR, Correr-Sobrinho L, Correr AB, et al. Solubility and dimensional change after setting of root canal sealers: a proposal for smaller dimensions of test samples. J Endod 2007;33:1110–6.

- Ørstavik D. Physical properties of root canal sealers: measurement of flow, working time, and compressive strength. Int Endod J 1983;16:99–107.

- Ye Q. The study and development of the nano-composite cement structure materials. New Build Mater 2001;1:4–6.

- Resende LM, Rached-Júnior FJ, Versiani MA, et al. A comparative study of physico-chemical properties of AH Plus, Epiphany, and Epiphany SE root canal sealers. Int Endod J 2009;42:785–93.

- Kogima T, Elliott JA. Effect of silica nanoparticles on the bulk flow properties of fine cohesive powders. Chem Eng Sci 2013;101:315–28.

- Wilson AD, Batchelor RF. Zinc oxide-eugenol cements: II. Study of erosion and disintegration. J Dent Res 1970;49:593–8.

- Hattori Y, Otsuka M. NIR spectroscopic study of the dissolution process in pharmaceutical tablets. Vibrational Spectroscopy 2011;57:275–81.

- Ji T. Preliminary study on the water permeability and microstructure of concrete incorporating nano-SiO2. Cem Concr Res 2005;35:1943–7.

- Viapiana R, Moinzadeh AT, Camilleri L, et al. Porosity and sealing ability of root fillings with gutta-percha and BioRoot RCS or AH Plus sealers. Evaluation by three ex vivo methods. Int Endod J 2016;49:774–82.

- Zhou HM, Shen Y, Zheng W, et al. Physical properties of 5 root canal sealers. J Endod 2013;39:1281–6.

- Kazemi RB, Safavi KE, Spangberg LS. Dimensional changes of endodontic sealers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1993;76:766–71.

- Clausen CA, Kartal SN, Arango RA, Green F 3rd. The role of particle size of particulate nano-zinc oxide wood preservatives on termite mortality and leach resistance. Nano-scale Res Lett 2009;6:427.

- Freeman MH, McIntyre CR. Comprehensive review of copper-based wood preservatives. Forest Products J 2008;58:6–27.

- Gorduysus M, Avcu N. Evaluation of the radiopacity of different root canal sealers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009;108:e135–40.

- Guerreiro-Tanomaru JM, Trindade-Junior A, Costa BC, et al. Effect of zirconium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles on physicochemical properties and antibiofilm activity of a calcium silicate-based material. ScientificWorldJournal 2014; 2014:1–6.

- Savioli RN. Study of the influence of each chemical component inGrossman cement on its physical properties [thesis]. Ribeirão Preto: University of São Paulo; 1992.

- Norman AD, Phillips AW, Swartz ML, Faankiewicz L. The effect of particle size on the physical properties of zinc oxide-eugenol mixtures. J Dent Res 1964;43:252–62.

- Fiebach K, Grimm D. Natural resins. In: Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 7th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2000.

- Padovani GC, Feitosa VP, Sauro S, et al. Advances in dental materials through nano-technology: facts, perspectives and toxicological aspects. Trends Biotechnol 2015; 33:621–36.