Enamel pearls in permanent dentition: case report and micro-CT evaluation

Objectives: To investigate the frequency, position, number and morphology of enamel pearls (EPs) using micro-computed tomography (μCT) and to report a case of an EP mimicking an endodontic/periodontic lesion.

Methods: A cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) was performed in a patient to evaluate a radio-opaque nodule observed on the left maxillary first molar during the radiographic examination. Additionally, 23 EPs were evaluated regarding frequency, position, number and morphology by means of μCT. The results were statistically compared using Student’s t-test for independent samples.

Results: 13 specimens presented one pearl, while 5 specimens presented two pearls. The most frequent location of the EPs was the furcation between the disto-buccal and the palatal roots of the maxillary molars. Overall, the mean major diameter, volume and surface area were 1.98 ± 0.85 mm, 1.76 ± 1.36 mm3 and 11.40 ± 7.59 mm2, respectively, with no statistical difference between maxillary second and third molars (p > 0.05). In the case report, CBCT revealed an EP between the disto-buccal and the palatal roots of the maxillary first left molar associated with advanced localized periodontitis. The tooth was referred for extraction.

Conclusions: EPs, located generally in the furcation area, were observed in 0.74% of the sample. The majority was an enamel-dentin pearl type and no difference was found in maxillary second and third molars regarding diameter, volume and surface area of the pearls. In this report, the EP mimicked an endodontic/periodontic lesion and was a secondary etiological factor in the periodontal breakdown. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology (2013) 0, 20120332. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20120332

Developmental abnormalities such as palatal grooves, cervical enamel projections or enamel pearls (EPs) may pre-dispose the affected area to plaque accumulation causing periodontal breakdown. The EP-associated lesion often presents as a periapical or a periodontal lesion with angular bone loss along the root surface on the radiograph. In some cases, its clinical features may result in drainage in the sulcus area, swelling, sinus tract, simulating an endodontic/periodontic lesion. A thorough examination including pulp vitality tests and careful radiographic examination is necessary to aid in the diagnosis and treatment options.

The first description of an EP was recorded in the first half of the 19th century and, since then, it has been referred to as enamel droplet, enamel nodule, enamel globule, enamel knot, enamel exostose, enameloma and adamantoma. The EP has been described as a well-defined globule of enamel, generally round, white, smooth and glasslike, that firmly adheres to the external root surface of teeth. Although it consists primarily of enamel, in most instances, a core of dentine or a pulp cavity may be found within it. Its aetiology remains obscure. The most acceptable theory is that the pearl develops because of a localized developmental activity of the Hertwig’s Epithelial Root Sheath cells that remained adherent to the root surface during root development differentiating into functioning ameloblasts. The EP has been evaluated in vivo and ex vivo using conventional radiography and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT). In the last decade, micro-computed tomography (μCT) has gained increasing significance as a non-invasive reproducible method for three-dimensional (3D) assessment of dental hard tissues. Using this technology, Anderson et al evaluated the mineral content gradient of EPs and found that the mineral content in the surface and deeper enamel regions of the pearl were similar to those observed in premolar enamel. To date, no study has attempted to investigate and compare the morphology of the EP in different teeth using μCT.

Thus, the aim of this study was to report a case of one EP associated with advanced localized periodontal destruction in a maxillary molar simulating an endodontic/periodontic lesion and to investigate the frequency, position, number and morphology of EPs using μCT. The null hypothesis was that the EPs located in maxillary second and third molars have a similar morphology.

Materials and methods

Case report

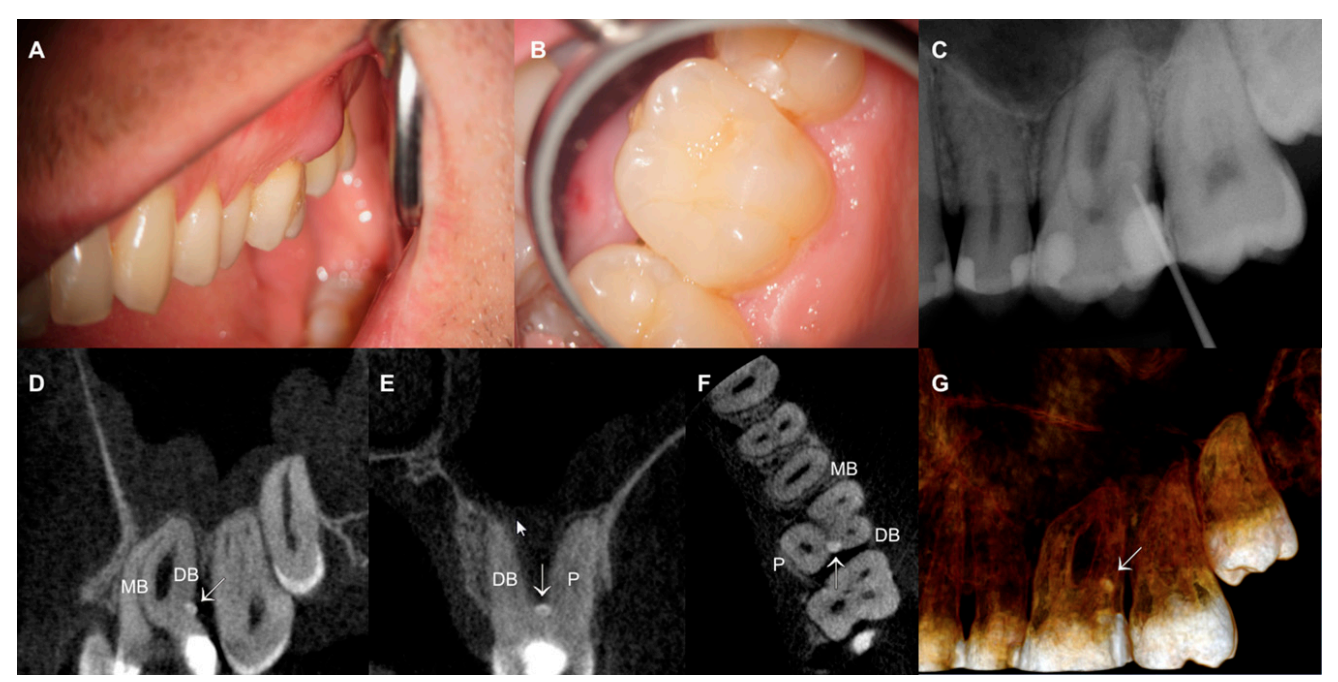

A 27-year-old male was referred by a general practitioner for the root canal treatment of the left maxillary first molar after presenting a swelling and a sinus tract on distobuccal surface (Figure 1a). The general health history was non-contributory and periodontal probing revealed a 10-mm pocket on the distal aspect of the tooth. The tooth was tender on palpation and exhibited no mobility or caries (Figure 1b). Pulp tests showed values within normal limits. The radiographic finding revealed the presence of deep resin restorations on the mesial and distal aspects of the crown and a narrow pulp chamber. Attempts to trace the sinus tract with a gutta-percha point revealed a round radio-opaque structure in the distal aspect of the tooth (Figure 1c). An informed consent was obtained and a CBCT scan (85 kVp, 10 mA, isotropic voxel size of 76 mm and exposure time of 10.80 s) with a limited cylindrical field of view (50337 mm) was performed (Kodak 9000 3D System; Carestream Health, Inc., Rochester, NY), following international statements. The CBCT exam showed the presence of a well-defined radio-opaque nodule comparable in density with the enamel of the crown between the disto-buccal and the palatal roots of left maxillary first molar (Figure 1d–g) consistent with the diagnosis of EP. Then, an immediate drainage of the purulent exudate was carried out and the tooth was referred for extraction and planning for an implant placement.

Micro-computed tomography evaluation

After the Ethics Committee’s approval was obtained (protocol 2009.1.972.58.4, CAAE 0072.0.138.000-09), 18 human teeth presenting one or more EPs on the root surface were selected from a pool of 2532 extracted teeth (origin and reasons for extraction unknown) and stored in labelled individual plastic vials containing 0.1% thymol solution until use. After being washed in running water for 24 h, each tooth was dried, mounted on a custom attachment and scanned in a μCT scanner (SkyScan 1174v2; Bruker-microCT, Kontich, Belgium) at an isotropic resolution of 19.6 mm. Images of each specimen were reconstructed from the apex to the coronal level with dedicated software (NRecon v. 1.6.3; Bruker-microCT), which provided axial cross-sections of the inner structure of the samples.

For the calculation of the morphometric parameters and surface representations of the specimens, the original greyscale images were processed with a slight gaussian low-pass filtration for noise reduction and an automatic segmentation threshold was used to separate root dentine from the enamel using CTAn v. 1.12 software (Bruker-microCT). This process entails choosing the range of grey levels necessary to obtain an image composed only of black and white pixels. The high contrast of enamel to the dentine yielded excellent segmentation of the specimens. Separately and for each slice, regions of interest containing the EP were chosen entirely to allow the calculation of its major diameter (mm), the volume (mm3) and the surface area (mm2). Then, a polygonal surface representation was constructed. The location of the EPs was acquired using DataViewer v. 1.4.4 (Bruker-microCT). CTVox v. 2.4 and CTVol v. 2.2.1 software (Bruker-microCT) were used for 3D visualization of the specimens.

The results of the morphological analysis of the EPs located at the second and third maxillary molars were statistically compared using Student’s t-test with the significance level set as 5% by using SPSS v. 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

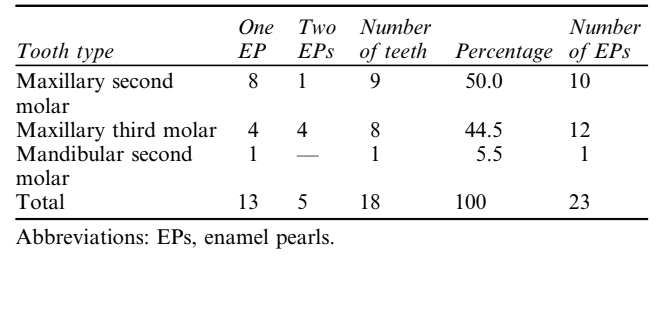

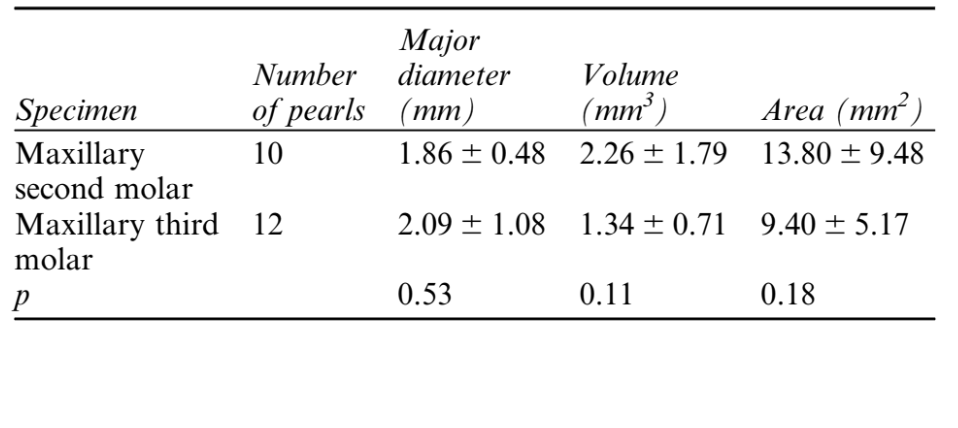

Table 1 shows the distribution of 23 EPs according to the type of tooth. Overall, 23 EPs were observed in 0.74% of the sample (18 out of 2532 teeth). It was found 10 EPs in 9 maxillary second molars, 12 pearls in 8 maxillary third molars and 1 pearl in 1 mandibular second molar.

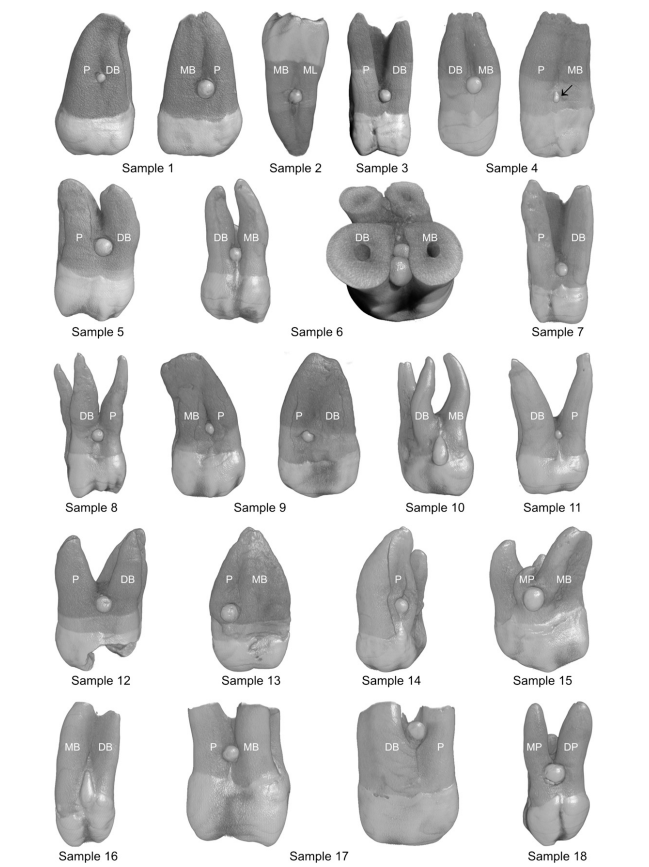

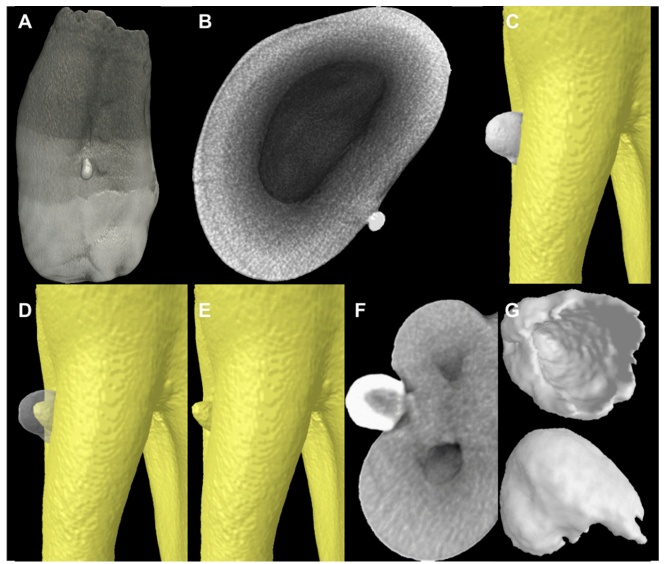

Figure 2 shows the 3D reconstruction of the sample. The EPs were located more frequently at the furcation between the disto-buccal and the palatal roots (n = 9; 39%), the disto-buccal and mesio-buccal roots (n = 5; 22%) and the mesio-buccal and palatal roots (n = 5; 22%). Macroscopically, EPs appeared spheroid, conical, ovoid, tear-drop or irregular shape.

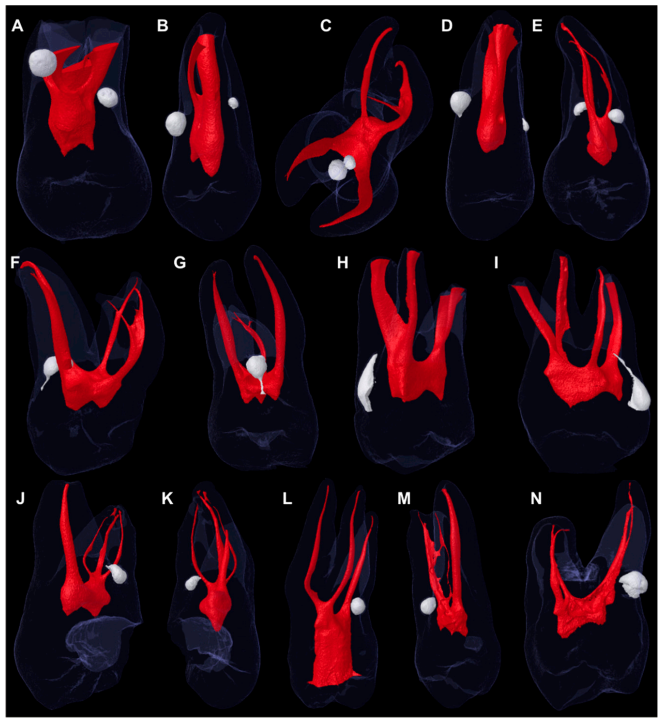

13 specimens (72%) presented only one pearl, while 5 specimens (28%) presented two pearls (Table 1; Figure 3a–e). The presence of cervical projections connecting the EP to the crown was also observed in four specimens (Figure 3f–i). No contact between the EPs and the root canal system was observed (Figure 3j–l, n). Only one specimen had a true EP, consisting entirely of enamel (Figure 4a, b), while the rest of the sample (n = 22; 96%) had a core of dentine (enamel-dentin pearl type; Figure 4c–g).

Overall, the mean major diameter, volume and surface area of the EPs were 1.98 ± 0.85 mm, 1.76 ± 1.36 mm3, and 11.40 ± 7.59 mm2, respectively, with no statistical difference between maxillary second and third molars (p > 0.05) (Table 2). Therefore, the null hypothesis was accepted.

Discussion

Clinically, an accurate early diagnosis of an EP may be helpful for the selection of an appropriate treatment aiming to prevent periodontal breakdown and avoiding unnecessary non-surgical root canal treatment or retreatment. In some cases, an EP does not produce symptoms, but as soon as it is detected, follow-up programs are crucial to prevent exacerbation of the lesion. If the pearl is exposed to the oral environment, odontoplasty, tunneling, root separation, resection, intentional replantation or extraction are indicated.

Anatomic abnormalities of root surfaces, such as EPs, are usually not apparent without the assistance of radiology. In a conventional radiographic examination, EP is depicted as dense, smooth radiopacity overlying any portion of the crown or root of an otherwise unaffected tooth. Despite the diagnosis of EP could be achieved with conventional radiograph, in the present study, the limited field of view CBCT scan was used to determine the extent of the lesion and its effect on surrounding structures. This imaging technique may be useful in selected cases of infrabony defects and furcation lesions where clinical and conventional radiographs do not provide the information needed for a proper management. Besides, the radiation dose of a limited field of view CBCT is similar to two periapical radiographs and in complex cases, evolving tooth extraction and implant placement, it may provide a dose savings over multiple traditional images. In the reported case, CBCT was valuable to show that the bone loss affected the furcation area and surrounding structures of left maxillary first molar and did not allow for a conservative treatment.

The reported prevalence of EPs has varied significantly among studies. Moskow and Canut reviewed previous studies on EPs and reported its prevalence ranging from 1.1–9.7%. This variation was associated with methodological and ethnic differences. EPs have a distinct predilection for the furcation area of molar teeth and furrow within the root structure. Although there are few reports of the occurrence of EPs on roots of maxillary premolars, canines and incisors, it is generally accepted that they are found most frequently on the roots of the maxillary molars followed by mandibular molars. When occurring on the roots of maxillary molars, they are most commonly seen between the disto-buccal and the palatal roots as in this case report.

In the present study, the frequency of EPs was lower (0.74%) than these results; however, it was consistent with two previous studies. Chrcanovic et al evaluated 45785 extracted teeth and found that 0.82% of the specimens presented one or more EPs. They also found that pearls were most frequent in the furcation between the disto-buccal and the palatal roots of maxillary first (43.03%) and second molars (39.24%). Akgül et al, in an in vivo study using CBCT scanning, reported that 0.83% of the molar teeth (36 out of 4334 specimens) had at least one EP. It is most common to find one EP per root, however, two of such structures located on opposite sides of the root can sometimes be found. According to Cavanha, the finding of three EPs is rare, and the presence of four pearls is exceptional. In the present study, only teeth with one (n = 13) or two pearls (n = 5) were identified.

EPs can also be connected to the cervical enamel extensions by a ridge of enamel. In the present study, this anatomical feature was observed in four specimens. In such cases, this extension of the enamel may contribute to enhancing plaque retention and protecting oral micro-organisms from the action of salivary enzymes and oral hygiene measures, pre-disposing a particular site to periodontitis. In the present study, it was observed that one small pearl was constituted solely of enamel, while the others have a core of dentine within. Root excrescences, which consist solely of enamel, are usually quite small (approximately 0.3 mm in diameter) and are called true EPs or simple EPs. Nevertheless, most of the pearls are enamel-dentin pearls, where the enamel layer caps a core of dentine. Some larger EPs may also contain pulp tissue, and these have been called enamel-dentin-pulp pearls.

The major diameter of the pearls ranged from 1.15 to 4.48 mm, with a mean of 1.98 mm, which is in accordance with previous studies. Risnes evaluated 8854 human molars and found that the diameter of the EPs ranged from 0.3 mm to 4 mm, mostly varying from 0.5 mm to 1.5 mm in diameter. Loh studied 5674 teeth and found that 57% of the pearls ranged in diameter from 1.0 mm to 1.9 mm. Sutalo et al analysed over 7000 teeth and found that the mean diameter of these enamel structures was 1.7 mm. The results of volume and surface area of the EPs achieved in the present study cannot be compared with others, as there is no information on this subject in the literature to date. Thus, the clinical relevance of such findings is still to be determined.

In conclusion, the evaluation of 18 molar teeth revealed the presence of 23 EPs located generally in the furcation area. The majority was an enamel-dentin pearl type and no difference was found in pearls located in maxillary second and third molars regarding diameter, volume and surface area. In this report, the EP mimicked an endodontic/periodontic lesion and was a secondary etiological factor in the periodontal breakdown.

Authors: MA Versiani, RC Cristescu, PC Saquy, JD Pécora and MD de Sousa-Neto

References:

- Cavanha AO. Enamel pearls. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1965; 19: 373–382.

- Chrcanovic BR, Abreu MH, Custodio AL. Prevalence of enamel pearls in teeth from a human teeth bank. J Oral Sci 2010; 52: 257–260.

- Goldstein AR. Enamel pearls as contributing factor in periodontal breakdown. J Am Dent Assoc 1979; 99: 210–211.

- Matthews DC, Tabesh M. Detection of localized tooth-related factors that predispose to periodontal infections. Periodontol 2000 2004; 34: 136–150.

- Moskow BS, Canut PM. Studies on root enamel (2). Enamel pearls. A review of their morphology, localization, nomenclature, occurrence, classification, histogenesis and incidence. J Clin Periodontol 1990; 17: 275–281.

- Risnes S. The prevalence, location, and size of enamel pearls on human molars. Scand J Dent Res 1974; 82: 403–412.

- Risnes S, Segura JJ, Casado A, Jimenez-Rubio A. Enamel pearls and cervical enamel projections on 2 maxillary molars with localized periodontal disease: case report and histologic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000; 89: 493–497.

- Saini T, Ogunleye A, Levering N, Norton NS, Edwards P. Multiple enamel pearls in two siblings detected by volumetric computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008; 37: 240–244.

- Skinner MA, Shiloah J. The role of enamel pearls in localized severe periodontitis. Quintessence Int 1989; 20: 181–183.

- Akgül N, Caglayan F, Durna N, Sümbüllü MA, Akgül HM, Durna D. Evaluation of enamel pearls by cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT). Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2012; 17: e218–e222.

- Romeo U, Palaia G, Botti R, Nardi A, Del Vecchio A, Tenore G, et al. Enamel pearls as a predisposing factor to localized periodontitis. Quintessence Int 2011; 42: 69–71.

- Lin HJ, Chan CP, Yang CY, Wu CT, Tsai YL, Huang CC, et al. Cemental tear: clinical characteristics and its predisposing factors. J Endod 2011; 37: 611–618.

- Lindere J, Linderer CJ. Handbuch der Zahnheilkunde. 1st edn. Berlin, Germany: Schlesinger; 1842.

- Kupietzky A, Rozenfarb N. Enamel pearls in the primary dentition: report of two cases. ASDC J Dent Child 1993; 60: 63–66.

- Anderson P, Elliott JC, Bose U, Jones SJ. A comparison of the mineral content of enamel and dentine in human premolars and enamel pearls measured by X-ray microtomography. Arch Oral Biol 1996; 41: 281–290.

- Gašperšič D. Histogenetic aspects of the composition and structure of human ectopic enamel, studied by scanning electron microscopy. Arch Oral Biol 1992; 37: 603–611.

- Darwazeh A, Hamasha AA. Radiographic evidence of enamel pearls in jordanian dental patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000; 89: 255–258.

- Versiani MA, Pécora JD, Sousa-Neto MD. The anatomy of two-rooted mandibular canines determined using micro-computed tomography. Int Endod J 2011; 44: 682–687.

- Pauwels R, Beinsberger J, Collaert B, Theodorakou C, Rogers J, Walker A, et al. Effective dose range for dental cone beam computed tomography scanners. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81: 267–271.

- AAE/AAOMR. Use of cone-beam computed tomography in endodontics Joint Position Statement of the American Association of Endodontists and the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011; 111: 234–237.

- Gašperšič D. Enamel microhardness and histological features of composite enamel pearls of different size. J Oral Pathol Med 1995; 24: 153–158.

- Loh HS. A local study on enamel pearls. Singapore Dent J 1980; 5: 55–59.

- Sutalo J, Ciglar I, Njemirovskij V. Incidence of enamel pearls in our population. Acta Stomatol Croat 1986; 20: 123–129.