Micro–computed Tomographic Evaluation of the Shaping Ability of XP-endo Shaper, iRaCe, and EdgeFile Systems in Long Oval-shaped Canals

Abstract

Introduction: This study evaluated the shaping ability of the XP-endo Shaper (FKG Dentaire SA, La Chaux- de-Fonds, Switzerland), iRaCe (FKG Dentaire SA), and EdgeFile (EdgeEndo, Albuquerque, NM) systems using micro–computed tomographic (micro-CT) technology.

Methods: Thirty long oval-shaped canals from mandibular incisors were matched anatomically using micro-CT scanning (SkyScan1174v2; Bruker-microCT, Kontich, Belgium) and distributed into 3 groups (n = 10) according to the canal preparation protocol (ie, XP-endo Shaper, iRaCe, and EdgeFile systems). Coregistered images, before and after preparation, were evaluated for morphometric measurements of the volume, surface area, structure model index (SMI), untouched walls, area, perimeter, roundness, and diameter. Data were statistically compared between groups using the 1-way analysis of variance post hoc Tukey test and within groups with the paired sample t test (α = 5%).

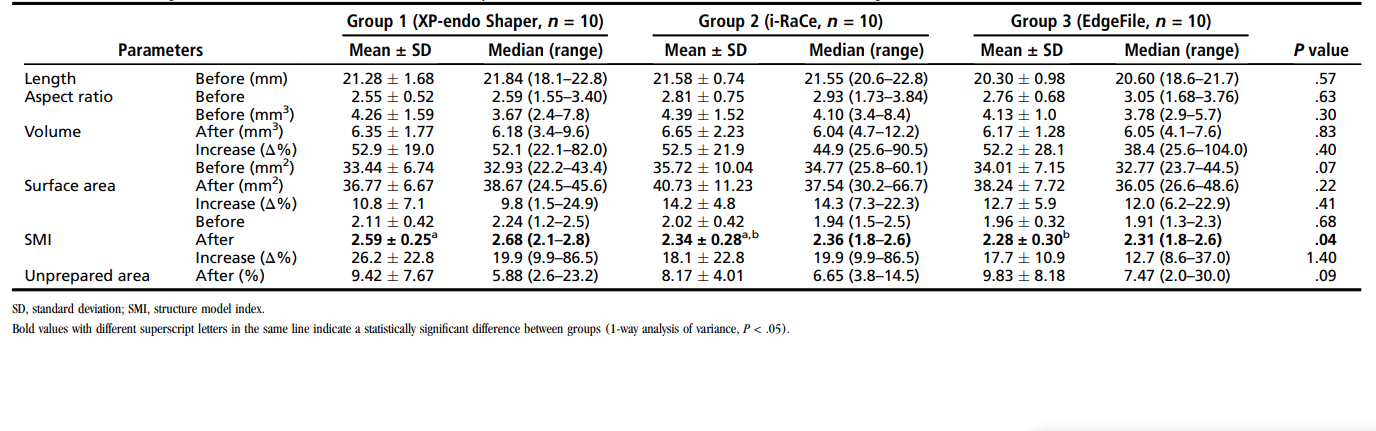

Results: Within groups, preparation significantly increased all tested parameters (P < .05). No statistical difference was observed in the mean percentage increase of the volume (〜52%) and surface area (10.8%–14.2%) or the mean percentage of the remaining unprepared canal walls between groups (8.17%–9.83%) (P > .05). The XP-endo Shaper significantly altered the overall geometry of the root canal to a more conical shape (SMI = 2.59) when compared with the other groups (P < .05). After preparation protocols, changes in area, perimeter, roundness, and minor and major diameters of the root canals in the 5 mm of the root apex showed no difference between groups (P > .05).

Conclusions: The XP- endo Shaper, iRaCe, and EdgeFile systems showed a similar shaping ability. Despite the XP-endo Shaper had significantly altered the overall geometry of the root canal to a more conical shape, neither technique was capable of completely preparing the long oval-shaped canals of mandibular incisors. (J Endod 2018;44:489–495)

The main goal of root canal preparation is to remove the inner layer of the dentin while allowing the irrigant to reach the entire length of the canal space, eradicating bacterial populations or at least reducing them to levels that allow for periradicular tissue healing.

However, it is widely recognized that fulfilling this goal with the available endodontic armamentarium may be a challenging task when preparing flattened or oval-shaped root canals. Therefore, to make canal shaping more efficient and predictable, several nickel-titanium (NiTi) instruments with an optimal geometry and surface have been developed within the last decades.

The iRaCe system (FKG Dentaire SA, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland) was introduced as a simplified sequence of the original RaCe system (FKG Dentaire SA). Its active cutting regions are electrochemically polished and have twisted areas with alternating cutting edges. Research findings on iRaCe instruments have shown some advantageous properties compared with other systems regarding the maintenance of the canal curvature. In recent years, the EdgeEndo company (Albuquerque, NM) has launched 4 different constant tapered systems (X1, X3, X5, and X7) to be used with the same handpiece, speed, kinematics, and torque as their specified competitor’s recommended settings. The reciprocating (X1) and rotary (X3, X5, and X7) instruments are made of an annealed heat treated NiTi alloy brand named Fire-Wire (EdgeEndo), which has been claimed to increase the cyclic fatigue resistance and torque strength of the instruments. More recently, a new file system known as the XP-endo Shaper (FKG Dentaire SA) was introduced. This snake-shaped instrument is made of a proprietary alloy (MaxWire [FKG Dentaire SA] [Martensite-Austenite electropolish-fleX]) that reacts at different temperature levels. The file has an initial taper of .01 in its M phase when it is cooled, but, upon exposure to body temperature (35◦C), the taper changes to .04 according to the molecular memory of the A phase. As stated by the manufacturer, the tip of the XP-endo Shaper, the Booster Tip, has 6 cutting edges and enables the instrument to start shaping after a glide path of at least ISO 15 and to gradually increase its working field to achieve ISO 30.

Several methodologies were developed to evaluate the shaping ability of NiTi systems, but currently 3-dimensional nondestructive high-resolution X-ray micro–computed tomographic (micro-CT) imaging is considered the gold standard. Even though there is accumulating evidence on the efficacy of several rotary and reciprocating systems, comprehensive knowledge regarding the shaping ability of the XP-endo Shaper, iRaCe, and EdgeFile (EdgeEndo) systems is still lacking. Therefore, the purpose of this ex vivo study was to evaluate the shaping ability of these instruments in long oval-shaped root canals of mandibular incisors using micro-CT imaging technology.

Material and Methods

Tooth Specimen Selection and Groups

After local ethics committee approval, 100 noncarious, straight, single-rooted human mandibular incisors with fully formed apices were randomly selected from a pool of extracted teeth, mounted on a custom attachment, and imaged separately at an isotropic resolution of 26.7 μm using a micro-CT device (SkyScan 1174v.2; Bruker microCT, Kontich, Belgium). The scanner parameters were set at 50 kV, 800 μA, 180◦ rotation around the vertical axis, and a rotation step of 0.7◦ using a 1-mm-thick aluminum filter. The acquired projection images were reconstructed into cross-sectional slices using NRecon v.1.6.9 software (Bruker-microCT) with a beam hardening correction of 10%, smoothing of 3, ring artifact correction of 3, and an attenuation coefficient ranging from 0.002 to 0.120.

Preoperative 3-dimensional (3D) models of the root and root canals were rendered (CTVol v.2.2.1, Bruker microCT) for qualitative evaluation of the canal configuration. Then, 3D and 2-dimensional (2D) parameters of the root canals were calculated according to a previous publication using CTAn v.1.14.4 software (Bruker microCT). 3D measurements (root canal length, volume, surface area, and the structure model index [SMI]) were based on a surface-rendered volume model of the root canal in the 3D space extending from the cementoenamel junction level on the buccal aspect of the root to the apex, whereas 2D morphometry (area, perimeter, roundness, and minor and major diameters) was performed at a 1-mm interval in the 5 mm of the root apex on individual binarized cross-sectional images of the root canal starting 0.5 mm from the apical foramen. The canal shape was classified by calculating the mean aspect ratio, defined as the ratio of the major to the minor diameter, of all slices in the 10 mm of the root apex. A canal was identified as a long oval-shaped canal when the ratio of the long to short canal diameter was >2 (ie, when 1 dimension was at least 2 times that of a measurement made at right angles).

Aiming to enhance the internal validity of the experiment, 30 mandibular incisors with a single long oval-shaped root canal were selected and matched to create 10 groups of 3 teeth based on the morphologic aspects of the root canal systems. Then, 1 tooth from each group was randomly assigned to 1 of the 3 experimental groups (n = 10) according to the canal preparation protocol (ie, XP-endo Shaper, iRaCe, or EdgeFile). After checking the normality assumption (Shapiro-Wilk test) and homoscedasticity (Levene test), the degree of homogeneity (baseline) of the 3 groups with respect to the 2D (area, perimeter, roundness, and diameter) and 3D root canal (length, volume, surface area, and SMI) morphometric parameters was statistically confirmed at a significance level of 5% (P > .05, 1-way analysis of variance test) (Tables 1 and 2).

Root Canal Preparation

Conventional access cavities were prepared, canals were accessed, and patency was confirmed with a size 10 K-file (FKG Dentaire SA). When the tip of the instrument was visible through the main foramen, 0.5 mm was subtracted to determine the working length (WL). No coronal flaring was performed, and a glide path was achieved to the WL with a size 15 K- file (FKG Dentaire SA). Then, root canal preparations were performed by previously trained operators in each system. In group 1 (n = 10), the tip of the XP-endo Shaper instrument was inserted into the canal, and the instrument was activated in the rotate mode (Rooter, FKG Dentaire SA; 800 rpm and 1.0 Ncm), applying long and light up-and-down movements. Once it reached the WL, 5 more up-and-down movements were applied over the entire WL, and the instrument was removed from the canal while it was rotating. In group 2, iRaCe R1 (15/.06), R2 (25/.04), and R3 (30/.04) instruments were sequentially used in rotary motion up to the WL (FKG Rooter motor, 600 rpm and 1.5 Ncm). In group 3, the Edge- File X1 instrument (25/.06) was activated in reciprocating motion using the WaveOne motor setting (VDW Silver motor; VDW GmbH, Munich, Germany) until it reached the WL. The final apical preparation was then performed using the EdgeFile X7 rotary instrument (30/.04) (VDW Silver motor; 350 rpm and 3 Ncm). In the iRace and EdgeFile groups, after instruments had negotiated to the WL, they were used with a light brushing motion. Irrigation was performed throughout the

preparation procedure with a total of 18 mL of a preheated 2.5% sodium hypochlorite solution (38◦C 1◦C) delivered using a 30-G NaviTip needle (Ultradent, South Jordan, UT) adapted to a disposable plastic syringe placed up to 2 mm short of the WL, with a gentle in-and-out movement. In all groups, the preparation protocol was repeated over the entire length of the canal until a size 30/.04 gutta-percha master point fit at the WL. Then, canals were flushed with 3 mL 17% EDTA (5 minutes), 3 mL sodium hypochlorite 2.5% (5 minutes), and 2 mL distilled water (1 minute) and dried with paper points. Roots were then submitted to a postoperative scan and reconstruction applying the initial parameter settings.

Micro-CT Analysis

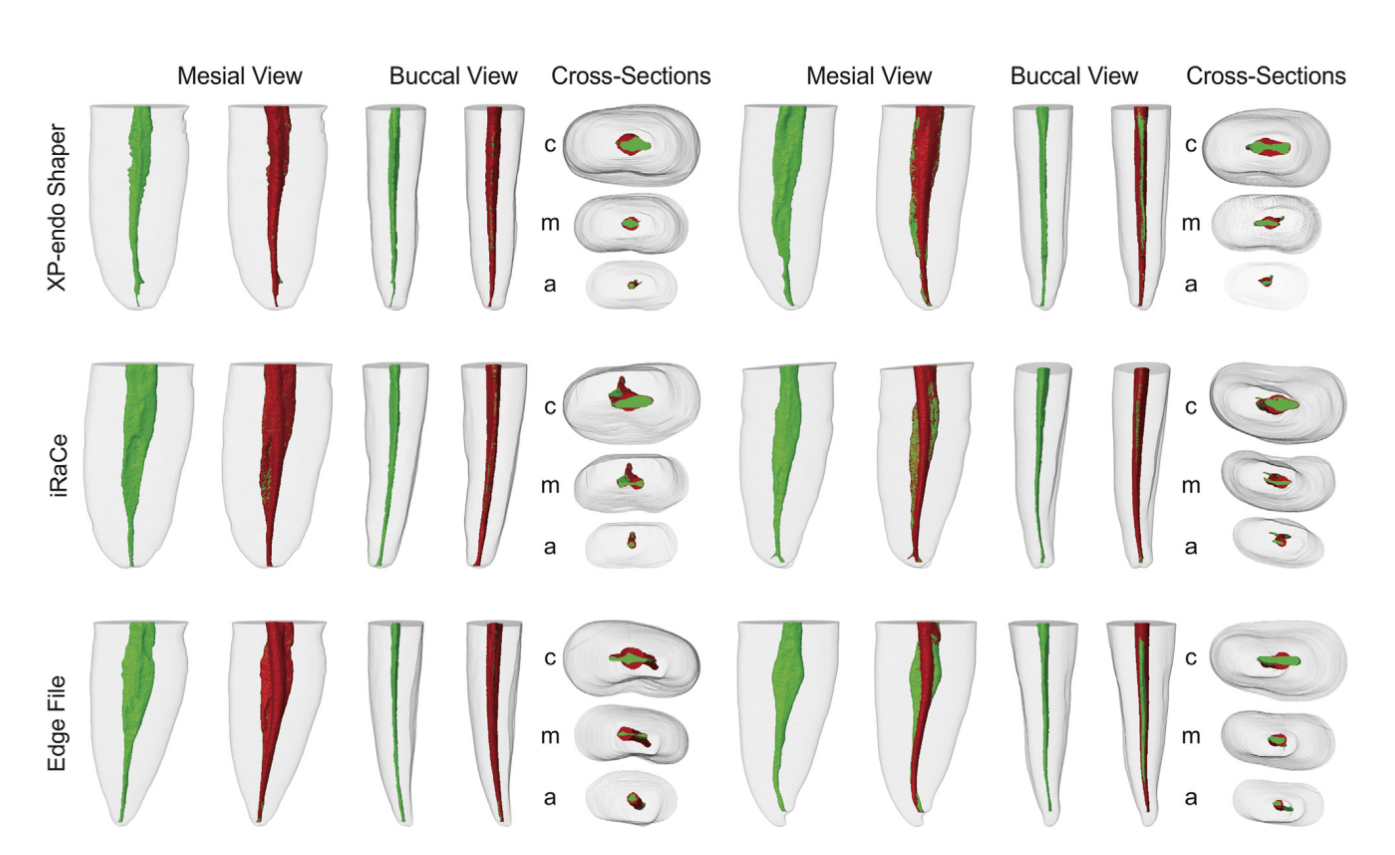

Pre- and postoperative models of the canals were rendered with CTAn v.1.14.4 software and coregistered with their respective preoperative data sets using the rigid registration module of the 3D Slicer 4.3.1 software (available from http://www.slicer.org). A qualitative comparison between groups was performed using color-coded models of the matched root canals (green and red colors indicate pre- and postoperative canal surfaces) with CTVol v.2.2.1 software (Bruker microCT) (Fig. 1).

Postoperative parameters (volume, surface area, SMI, area, perimeter, roundness, and minor and major diameters) were acquired with CTAn v.1.14.4 software. Then, the increment in diameter per millimeter in the apical canal (taper) was determined before and after preparation in both the mesiodistal and buccolingual directions. The mean percentage increases (D%) of the volume, surface area, and SMI parameters were calculated according to the formula ([Pa–Pb]/ Pb)*100, where Pb and Pa represent the parameters’ values assessed before and after preparation, respectively. Spatially registered surface models of the roots were also compared regarding the unprepared area of the root canal, which was calculated by using the distances between the surface of the root canals before and after preparation determined at every surface point. Then, the percentage of the remaining unprepared surface area was calculated using the formula (Au/Ab)*100, where Au represents the unprepared canal area and Ab the root canal area before preparation. An examiner blinded to the preparation protocols performed the analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Data were normally (Shapiro-Wilk test) and homoscedastically (Levene test) distributed regarding the canal length, surface area, SMI, area, perimeter, roundness, and diameter and compared between groups using the 1-way analysis of variance post hoc Tukey test, whereas the statistical analyses of the volume and untouched canal walls were performed with the Kruskal-Wallis test. The paired sample t test was used to compare the pre- and postpreparation parameters within groups. The significance level was set at 95% (SPSS v17.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Tables 1 and 2 display the analysis of the tested 3D (canal length, volume, surface area, SMI, and unprepared area) and 2D (area, perimeter, roundness, and minor and major diameters) parameters, respectively, before and after root canal preparation of 30 mandibular incisors using different systems. In general, the preparation protocols significantly increased all measured parameters in each group (P < .05). Qualitative evaluation, displayed as superimpositions of unprepared (green) and prepared (red) areas, showed that all groups maintained the overall canal shape. Canals presenting a more flatlike geometry or a larger buccolingual extension showed more areas of untouched canal walls after preparation (Fig. 1).

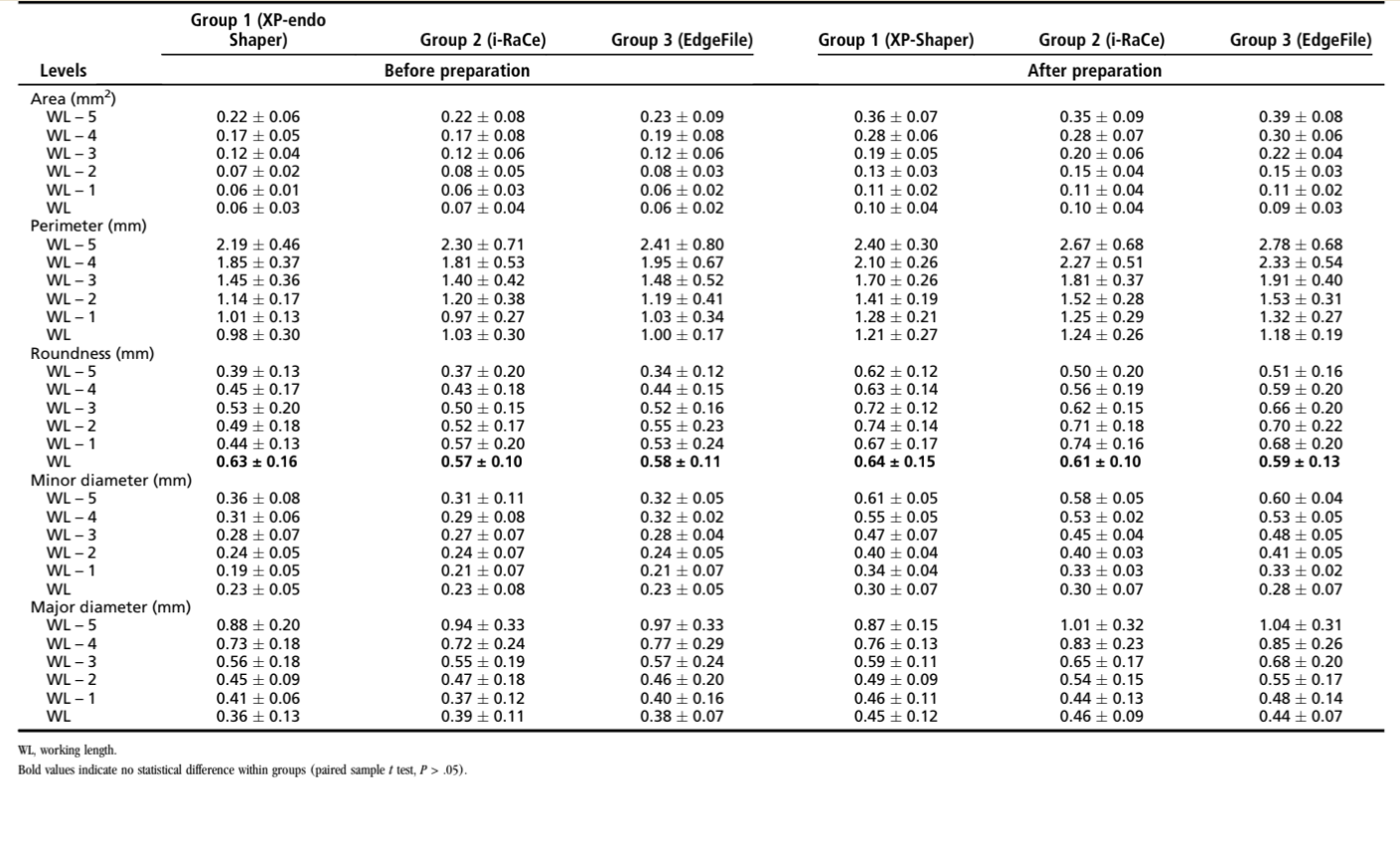

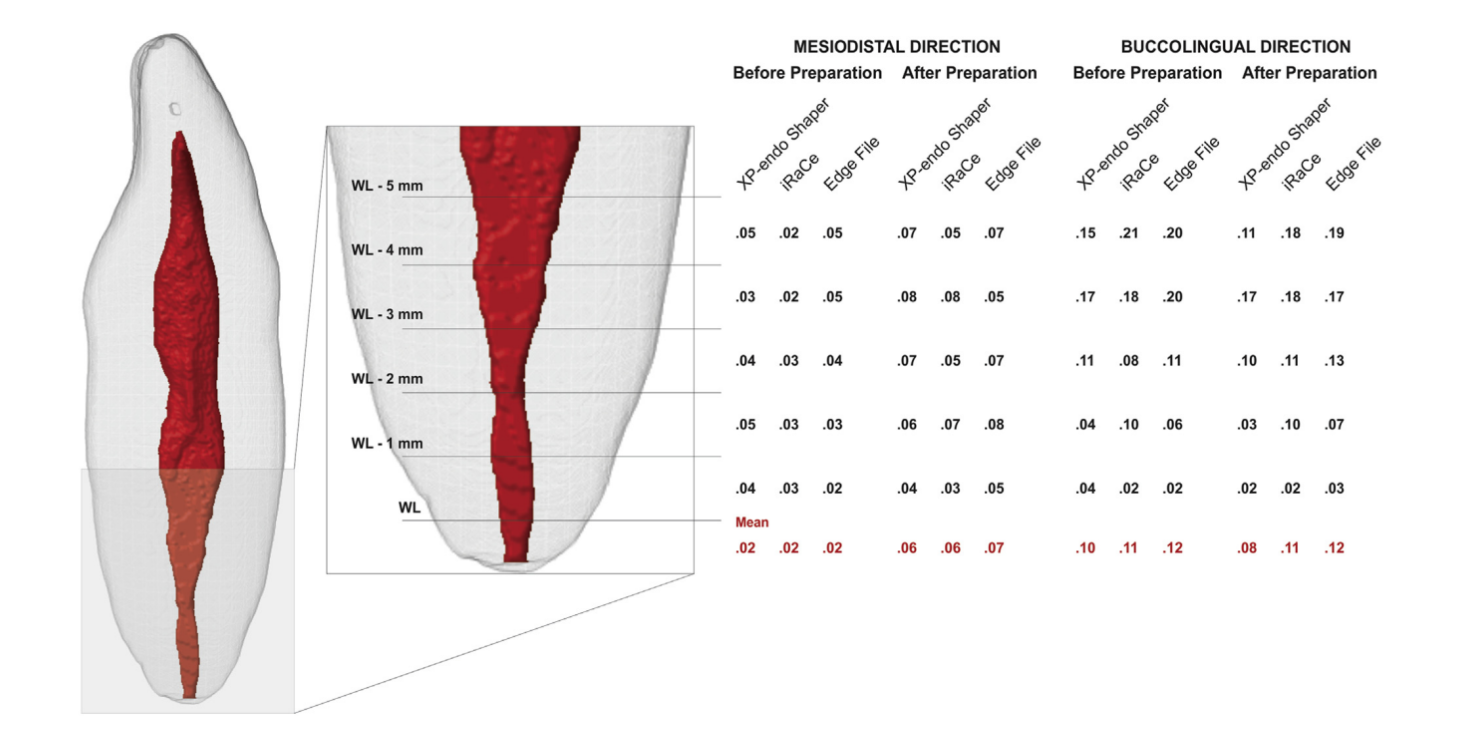

No statistical difference was observed between groups regarding the mean percentage increase of the volume (〜52%) and surface area (10.8%–14.2%) or the mean percentage of the remaining unprepared surface area (8.17%–9.83%) (Table 1, P > .05). Regarding the percentage increase of the SMI parameter, the XP-endo Shaper system significantly altered the overall 3D geometry of the root canal (SMI) to a more conical shape (2.59) when compared with the iRaCe (2.34) and EdgeFile (2.28) systems (Table 1, P < .05). A comparison of the 2D morphometric parameters of the root canals in the 5 mm of the root apex showed no difference between groups (Table 2, P > .05). After preparation, the mean apical canal taper increased 3 times in the mesiodistal direction in all groups (from .02–.06), whereas no significant variation was observed in the buccolingual direction (Fig. 2).

Discussion

This study evaluated the effects of 2 recently launched preparation systems (XP-endo Shaper and EdgeFile) on root canal geometry using micro-CT technology. The iRaCe rotary system was used as a reference technique for comparison. Despite dissimilarities in the cross-sectional design and kinematics reported to affect the shaping ability of NiTi preparation systems, a comparison between groups after preparation revealed no differences in the percentage increase of the volume and surface area, the unprepared canal surfaces, and some 2D parameters (area, perimeter, roundness, and diameter) in this study. These results may be explained by the mode action of the XP-endo Shaper and the similar dimensions of the final instruments used in the other experimental groups. The manufacturer has claimed that the NiTi alloy that the XP-endo Shaper is made of can shift its crystalline structure at body temperature to adapt to the root canal wall. Operating at 800 rpm, its adaptive core design (ISO size 30/.01) is able to start shaping a root canal at ISO size 15 and to achieve ISO size 30, and also increase the taper from .01 to at least .04, reaching a final canal preparation of a minimum 30/.04 in size, which are the dimensions of the final instruments used in the EdgeFile and iRace groups.

The surface convexity (3D geometry) of the root canal and the cross-sectional shape at the apical third in this study were evaluated using SMI and roundness morphometric parameters. An ideal plate, cylinder, and sphere have SMI values of 0, 3, and 4, respectively, whereas the roundness value of a discreet 2D object ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 signifying a line and 1 a perfect circle. At the apical third, the similarity of the groups regarding the roundness values after preparation (Table 2) can be justified because the root canals used to be anatomically more round in shape at this level. Additionally, as it would be expected after using tapered rotary and reciprocating instruments, the increasing of the SMI values showed that the long oval-shaped root canals became more cone frustum shaped after preparation. Interestingly, despite its specific preset shape, small diameter, and narrow taper, the XP-endo Shaper instrument significantly changed the root canal to a more conical shape (SMI = 2.59) than the EdgeFile (SMI = 2.28) and iRace (SMI = 2.34) systems (Table 1). This may be explained because the XP-endo Shaper instrument must be activated at a high rotational speed using long up-and-down movements throughout canal preparation.

Even with the progress made with the development of NiTi instruments with different metallurgical properties and geometric designs, in this study the quality of the root canal preparation was less than ideal. In agreement with previous reports, all tested systems have left a relatively high mean percentage of untouched canal walls (8.17%– 9.83%), mostly when the canal shape had a flatlike geometry, which confirms a previous statement that variations in canal geometry before shaping procedures have more influence on the changes that occurred during preparation than the instrumentation techniques themselves. Untouched areas in necrotic canals may harbor unaffected residual bacterial biofilms and serve as a potential cause of persistent infection. Considering that the remaining infection is an important risk factor for post-treatment apical periodontitis, chemomechanical preparation assumes a pivotal role in treatment because it acts mechanically and chemically on bacterial communities colonizing the main canal. The mean range of the untouched canal areas in this study was lower compared with previous reports using a similar methodology, probably because of the differences in the sampling approaches and the preparation protocols; however, no difference was observed among the experimental groups, possibly because of the light brushing motion used after the iRaCe and EdgeFile instruments reached the WL.

In the present study, the major diameter of the root canal was defined as the distance between the 2 most distant pixels in the binarized canal image, whereas the minor diameter was the longest chord through the root canal that could be drawn in the direction orthogonal to that of the major diameter. After preparation, the minor and major diameters at the apical canal increased from 0.23–0.30 mm and from 0.36– 0.45, respectively (Table 2). This means that the final preparation diameter at the WL was equivalent to ISO sizes 30 and 45 in the mesiodistal and buccolingual directions, respectively, which may be also explained by the brushing motion used with the final instruments. On the other hand, the average canal taper increased mostly in the mesiobuccal direction, but, as it would be expected after using constant tapered instruments, a continuous taper increasing progressively from the apical to the coronal direction was not possible to be observed (Fig. 2). This may be explained by anatomic irregularities on the original shape of the root canal system, which avoid instruments to touch all canal wall surfaces (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

The key role of laboratory-based studies is to develop well- controlled conditions that can reliably compare certain factors. Therefore, in the present study, care was taken to ensure that the sample was anatomically matched in terms of preoperative geometric parameters determined by micro-CT imaging. This procedure creates a reliable baseline and ensures the comparability of the groups by standardization of the canal morphology in each sample, enhancing internal validity and potentially eliminating significant anatomic biases that may confound the outcomes. In addition, long oval-shaped canals were selected because this anatomic variation has been considered a difficult challenge in clinical practice, and root canals were prepared by dentists with expertise in each 1 of the tested protocols.

The concept of using a single NiTi instrument to prepare the entire root canal was proposed a few years ago. In several clinical situations, this is an interesting proposal because it may be cost-effective and may shorten the learning curve for practitioners to adopt the new technique. Lately, several manufacturers have been developing instruments following this ‘‘one file shaper’’ proposal, such as the Self-Adjusting File (ReDent-Nova, Ra’anana, Israel), Reciproc (VDW), and WaveOne (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) systems. In this study, the single-file XP-endo Shaper was as effective in preparing long oval-shaped canals of mandibular incisors as the other tested multiple-file systems. However, it was unable to reach areas that the other instruments could not access despite its extreme flexibility and capacity to contract and expand within the root canal, as stated by the manufacturer. Nonetheless, it is also important to point out that in this study the XP-endo Shaper protocol was finished when a size 30/.04 gutta-percha master point fit at the WL, which happened very fast in most of the samples as soon as the instrument reached the WL and 5 more up-and-down movements were applied. Therefore, it is plausible to hypothesize that the shaping ability of the XP-endo Shaper could be optimized by increasing the preparation time, the number of up-and-down movements, and/or its rotational speed. This remains to be determined by further studies.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that the XP-endo Shaper, iRaCe, and EdgeFile systems showed a similar shaping ability. Despite the XP-endo Shaper system significantly altering the overall geometry of the root canal to a more conical shape, neither technique was capable of completely preparing the long oval-shaped canals of mandibular incisors.

Authors: Marco A. Versiani, Kleber K.T. Carvalho, Jardel F. Mazzi-Chaves, Manoel D. Sousa-Neto

References:

- Siqueira JF Jr, Roças IN. Clinical implications and microbiology of bacterial persistence after treatment procedures. J Endod 2008;34:1291–301.

- Versiani MA, Pécora JD, de Sousa-Neto MD. Flat-oval root canal preparation with self-adjusting file instrument: a micro-computed tomography study. J Endod 2011;37:1002–7.

- Marceliano-Alves MF, Sousa-Neto MD, Fidel SR, et al. Shaping ability of single-file reciprocating and heat-treated multifile rotary systems: a micro-CT study. Int Endod J 2015;48:1129–36.

- Siqueira JF Jr, Alves FR, Versiani MA, et al. Correlative bacteriologic and micro- computed tomographic analysis of mandibular molar mesial canals prepared by self-adjusting file, reciproc, and twisted file systems. J Endod 2013;39:1044–50.

- Versiani MA, Leoni GB, Steier L, et al. Micro-computed tomography study of oval-shaped canals prepared with the self-adjusting file, reciproc, waveone, and Pro-Taper universal systems. J Endod 2013;39:1060–6.

- Saber SE, Nagy MM, Schafer E. Comparative evaluation of the shaping ability of Pro-Taper Next, iRaCe and Hyflex CM rotary NiTi files in severely curved root canals. Int Endod J 2015;48:131–6.

- Baumann MA. Reamer with alternating cutting edges - concept and clinical application. Endod Topics 2005;10:176–8.

- EdgeEndo. EdgeFile X1 directions for use. Available at: http://edgeendo.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/DFU-EdgeFile-x1.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2017.

- FKG Dentaire SA. XP-Endo shaper: the one to shape your success. Available at: http:// www.fkg.ch/sites/default/files/201704_fkg_xp_endo_shaper_brochure_v4_en_web.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2017.

- Bayram HM, Bayram E, Ocak M, et al. Effect of ProTaper Gold, Self-Adjusting File, and XP-endo Shaper instruments on dentinal microcrack formation: a micro-computed tomographic study. J Endod 2017;43:1166–9.

- Peters OA, Laib A, Gohring TN, Barbakow F. Changes in root canal geometry after preparation assessed by high-resolution computed tomography. J Endod 2001; 27:1–6.

- Versiani MA, Pécora JD, Sousa-Neto MD. Microcomputed tomography analysis of the root canal morphology of single-rooted mandibular canines. Int Endod J 2013;46: 800–7.

- Wu MK, R’Oris A, Barkis D, Wesselink PR. Prevalence and extent of long oval canals in the apical third. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;89:739–43.

- Markvart M, Darvann TA, Larsen P, et al. Micro-CT analyses of apical enlargement and molar root canal complexity. Int Endod J 2012;45:273–81.

- Gagliardi J, Versiani MA, de Sousa-Neto MD, et al. Evaluation of the shaping characteristics of ProTaper Gold, ProTaper NEXT, and ProTaper Universal in curved canals. J Endod 2015;41:1718–24.

- Paqué F, Ganahl D, Peters OA. Effects of root canal preparation on apical geometry assessed by micro-computed tomography. J Endod 2009;35:1056–9.

- Azim AA, Piasecki L, da Silva Neto UX, et al. XP Shaper, a novel adaptive core rotary instrument: micro-computed tomographic analysis of its shaping abilities. J Endod 2017;43:1532–8.

- Elnaghy AM, Elsaka SE. Torsional resistance of XP-endo Shaper at body temperature compared with several nickel-titanium rotary instruments. Int Endod J 2017 Aug 1; http://doi.org/10.1111/iej.12815 [Epub ahead of print].

- Hildebrand T, Rüegsegger P. Quantification of bone micro architecture with the structure model index. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 1997;1: 15–23.

- Versiani MA, Alves FR, Andrade-Junior CV, et al. Micro-CT evaluation of the efficacy of hard-tissue removal from the root canal and isthmus area by positive and negative pressure irrigation systems. Int Endod J 2016;49:1079–87.

- Siqueira JF Jr, Perez AR, Marceliano-Alves MF, et al. What happens to unprepared root canal walls: a correlative analysis using micro-computed tomography and histology/scanning electron microscopy. Int Endod J 2017 Mar 17; http://doi.org/10.1111/iej.12753 [Epub ahead of print].

- Paqué F, Peters OA. Micro-computed tomography evaluation of the preparation of long oval root canals in mandibular molars with the self-adjusting file. J Endod 2011;37:517–21.

- Al-Omari MA, Aurich T, Wirtti S. Shaping canals with ProFiles and K3 instruments: does operator experience matter? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010;110:e50–5.

- Yared G. Canal preparation using only one Ni-Ti rotary instrument: preliminary observations. Int Endod J 2008;41:339–44.