Comparison of the Intraosseous Biocompatibility of AH Plus, EndoREZ, and Epiphany Root Canal Sealers

Abstract

To evaluate the intraosseous biocompatibility of AH Plus, EndoREZ, and Epiphany root canal sealers as recommended by the Technical Report #9 of the Fédération Dentaire Internationale (FDI). Thirty guinea pigs, 10 for each material, divided into experimental periods of 4 and 12 weeks, received one implant on each side of the lower jaw symphysis. At the end of the observation periods, the animals were killed and the specimens prepared for routine histological examination. After analyzing both periods, the inflammatory tissue reaction to EndoREZ was considered severe. In the AH Plus group, the reaction changed from severe to moderate, while it was observed biological compatibility to Epiphany with bone formation and none to slight inflammatory reaction. It was concluded that Epiphany root canal sealer was the only material that presented intraosseous biocompatibility within the two analyzed periods. (J Endod 2006;32:656 – 662)

Success in root canal treatment depends on the complete removal of the infected canal contents, followed by obturation using a material of adequate compatibility to avoid possible irritation to the periradicular tissues. Because tissue injury induced by intracanal procedures may result in unfavorable responses to treatment, the practitioner’s choice on procedures to be used during root canal treatment should rely on those that are known to cause as little damage as possible. It has been demonstrated that foreign materials, such as root canal sealers, trapped into periradicular tissues after endodontic treatment can perpetuate apical periodontitis.

It has also been shown that biocompatibility to the periradicular tissues is the most important requisite, because any material not biologically acceptable may be responsible for failures. In regard to the biological properties of endodontic materials, there is a broad range of characteristics that should be considered. The methodologies to evaluate the parameters comprise, initial tests, secondary tests, and usage studies. The initial evaluation should comprise in vitro methods of assessing the toxicity profile of the material. The secondary tests should be performed in vivo, in laboratory animals, and can include implantation experiments. The usage studies are carried out in primates or human beings.

The materials that are currently used in clinical practice comprised resin-, zinc oxide-eugenol-, glass ionomer-, calcium hydroxide-, and silicone-based endodontic sealers. Resin filling materials have steadily gained popularity and are now accepted as root canal sealers and improvements in adhesive technology have fostered attempts to reduce apical and coronal leakage by bonding to root canal walls. Thus, the newly methacrylate-based resin sealers EndoREZ and Epiphany have been recently developed. The biological properties of EndoREZ have been previously investigated regarding its cytotoxicity and tissue biocompatibility. Otherwise, the biological properties for Epiphany, a dual curable dental resin composite sealer, are poorly investigated.

It has been stated that the biological basis for root canal therapy is lagging behind the impressive technological advances in Endodontics. However, although required before being promoted for clinical use, the majority of the materials lack even basic safety testing.

To date, no studies have been conducted to histologically analyze the effect of Epiphany implantation in bone. Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the biological properties of the newly developed methacrylate-based root canal sealers EndoREZ and Epiphany, comparing to a conventional, well established epoxy-amine resin root canal sealer AH Plus, using the protocol recommended by the Fédération Dentaire Internationale (FDI).

Materials and Methods

The materials evaluated were AH Plus (Dentsply, DeTrey, Konstanz, Germany), EndoREZ (Ultradent Products, Inc., South Jordan, UT), and Epiphany (Pentron Clinical Technologies, Wallingford, CT) root canal sealers. All materials were prepared according to the manufacturer’s recommendation for their clinical use, and loaded into Teflon carriers (Polytetrafluorethylene, DuPont, HABIA, Knivsta, Sweden), ensuring that air was not entrapped. The protocol for this experiment was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Uberlândia and the experiment was carried out in accordance with the ‘Principles of Laboratory Animal Care’ (NIH, No. 86-23, 1985).

The intraosseous implant in the guinea pig mandible and the standardized methods to evaluate the biological properties recommended by the Technical Report #9 FDI were used. Thirty guinea pigs (weighing ~800 g) were selected and each animal received two implants of the same material. Ten specimens were used for each material and observation period. Additionally, the connective tissue response alongside the lateral wall outside the Teflon cup served as a negative control for the technique.

The animals were anesthetized intraperitoneally with 0.6 ml ketamine containing acepromazine in a 1:1 proportion. To prevent local discomfort, 0.6 ml of 2% xylocaine with epinephrine (1:100,000) was injected in the mucobuccal fold of the mandibular incisors region. The submandibular area was shaved and the skin disinfected with 5% tincture of iodine. The distal ventral symphyseal region of mandible was exposed surgically under antiseptic conditions through an incision into the skin and muscle tissue. The mandibular bone on both sides of the symphysis was exposed, and cylindrical holes with a diameter of 2 mm and depth of 2 mm were prepared with burs, under sterile physiological saline irrigation. Sterilized cylindrical Teflon cups, open at one end, and with their outer surfaces threaded to provide retention grooves, were filled under sterile conditions with the materials and inserted into the bony cavities in such a way that the filling materials were in contact with bone, preserving the sterile condition. The cylinders were 2.0 mm long and had an inner diameter of 1.3 mm and an outer diameter of 2.0 mm. Random samples of the cylinders were placed in tubes of Brewer’s thioglycollate media and incubated aerobically for 4 days to determine their sterility.

When the cups were in place, the soft tissues were replaced and sutured independently with a 3-0 resorbable material. The observation periods were 4 and 12 weeks, when the guinea pigs were killed, the mandible was dissected out and the bone adjacent to the cups in situ sectioned in 10-mm blocks. The specimens were immersed in 10% buffered formalin solution and prepared for routine histological examination. Serial sections, with the microtome set at 5-µm thickness, were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for cellular recognition. Selected slides were stained using the Masson’s Trichrome and Brown and Brenn techniques for collagen and bacterial contamination recognition.

The interface at the opening of the cup, between the material and the bone, was examined and evaluated for the intensity of the inflammation. The FDI criteria evaluation is exclusively qualitative and no scoring index was used. Hence, the overall level of the tissue reaction was rated as none to slight, moderate, and severe depending of the presence or absence of neutrophilic leukocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, giant foreign body cells, dispersed material, capsule, newly formed healthy bone, necrotic tissue, and resorption.

Two independent observers blindly evaluated the reactions. Previously, however, each investigator was calibrated by twice scoring a standard set of 50 slides regarding the intensity and type of the inflammatory reaction. The interexaminer agreement, calculated as Cohen’s kappa, ranged from 0.8 to 0.95. Intraexaminer reproducibility was evaluated by a double scoring of 25 randomly selected slides at 1-month interval. In this case, Cohen’s kappa ranged from 0.85 to 0.91. It was considered biologically acceptable when the material showed none to slight reaction at both experimental periods, or moderate reaction at 4 weeks that diminished at 12 weeks.

Results

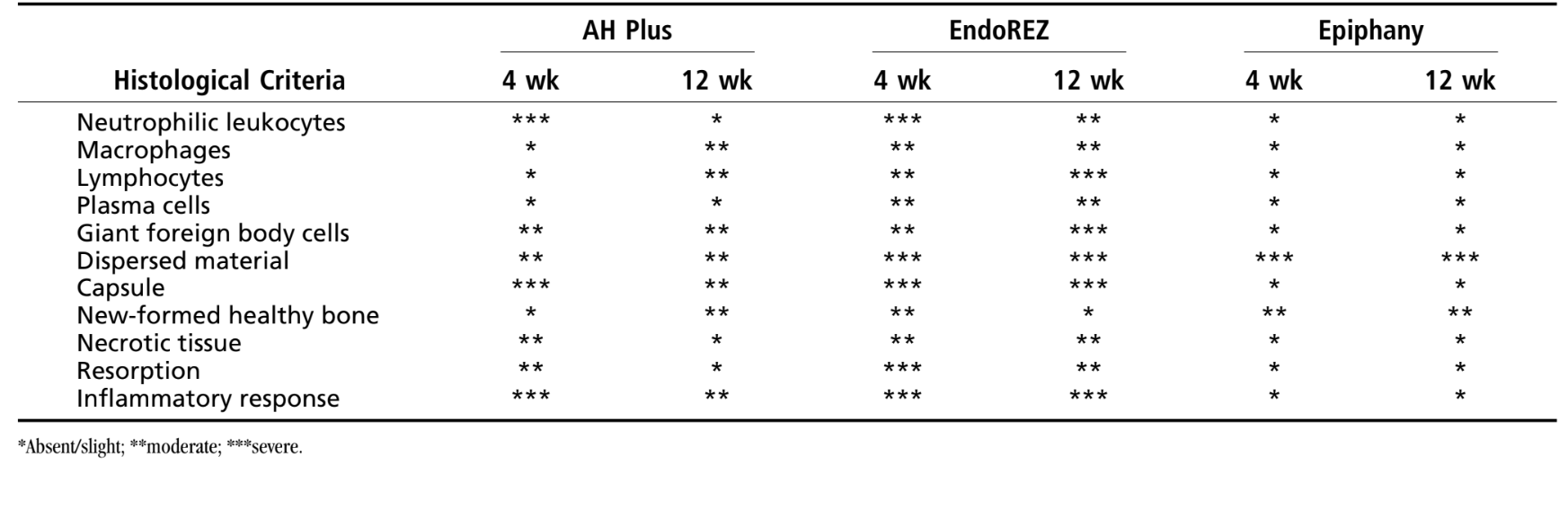

The number of intraosseous implants and the inflammatory response intensity are presented in Table 1. The histological evaluation of the materials at 4 and 12 weeks are summarized in Table 2.

None of the slides stained by the Brown and Brenn technique showed the presence of bacterial colonization in any of the experimental implants. The cylinders stored with those producing growth in the culture media were negative. The connective tissue response alongside the lateral wall outside the Teflon cups of all specimens served as a negative control for the technique. It was possible to observe that the grooves in the outer surface of the cups were filled with new bone tissue, and a thin layer of connective tissue, without inflammatory reaction, could be seen between the cup and bone at all observation periods in all specimens tested.

Four-Wk Observations

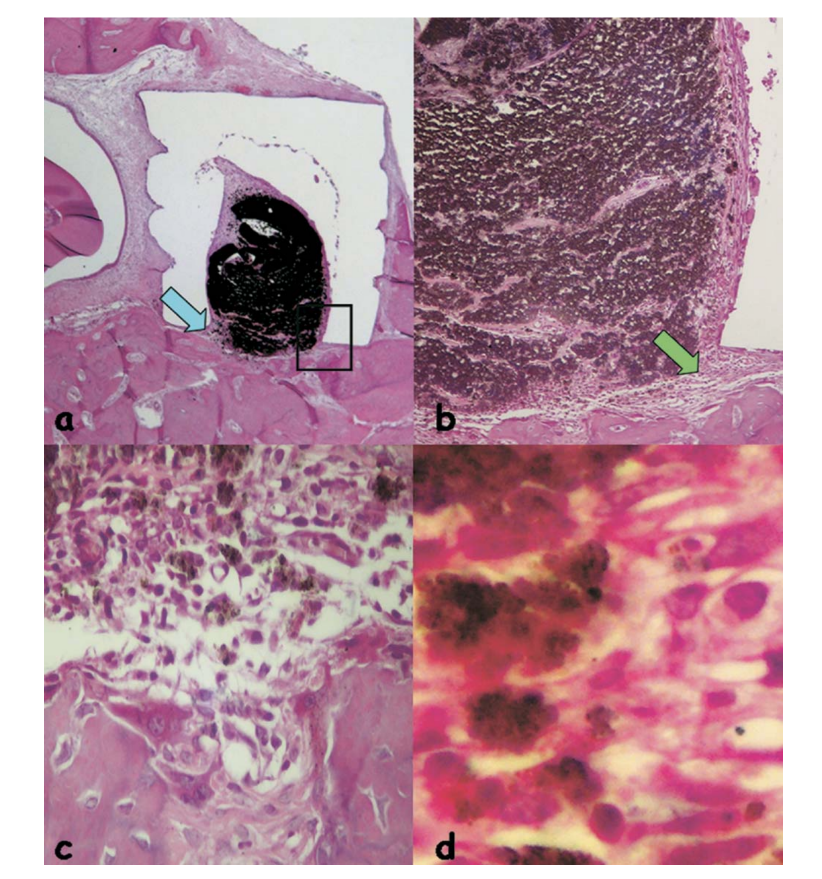

AH Plus

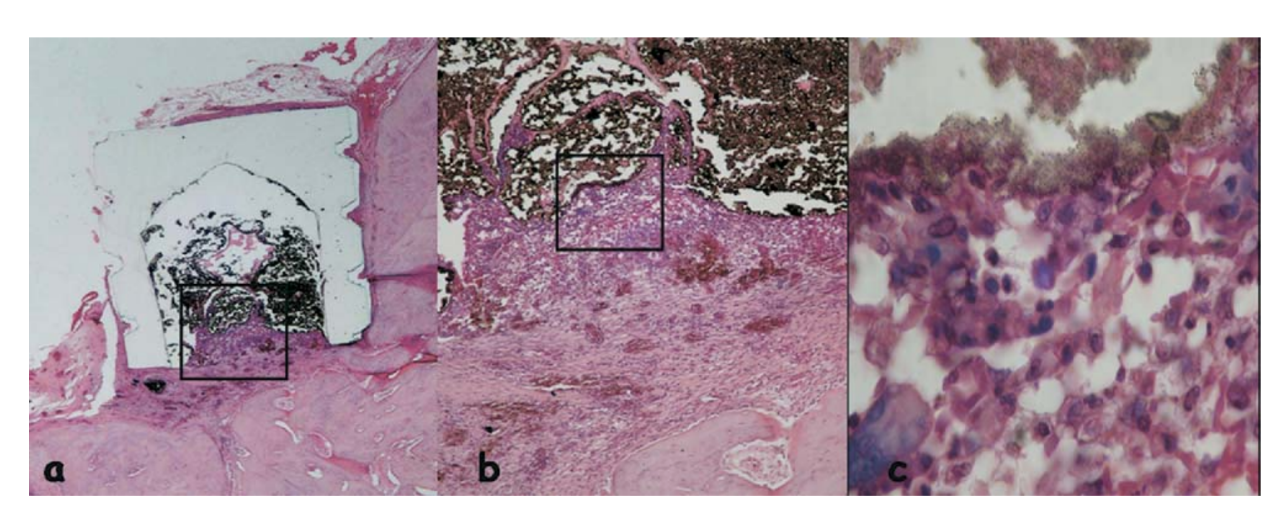

The reaction was considered severe. There was a thin layer of connective tissue interposing between the material and the bone (Fig. 1b) and the intense inflammatory infiltration showed the presence of lymphocytes, macrophages and giant foreign body cells, necrotic bone fragments (Fig. 1c).

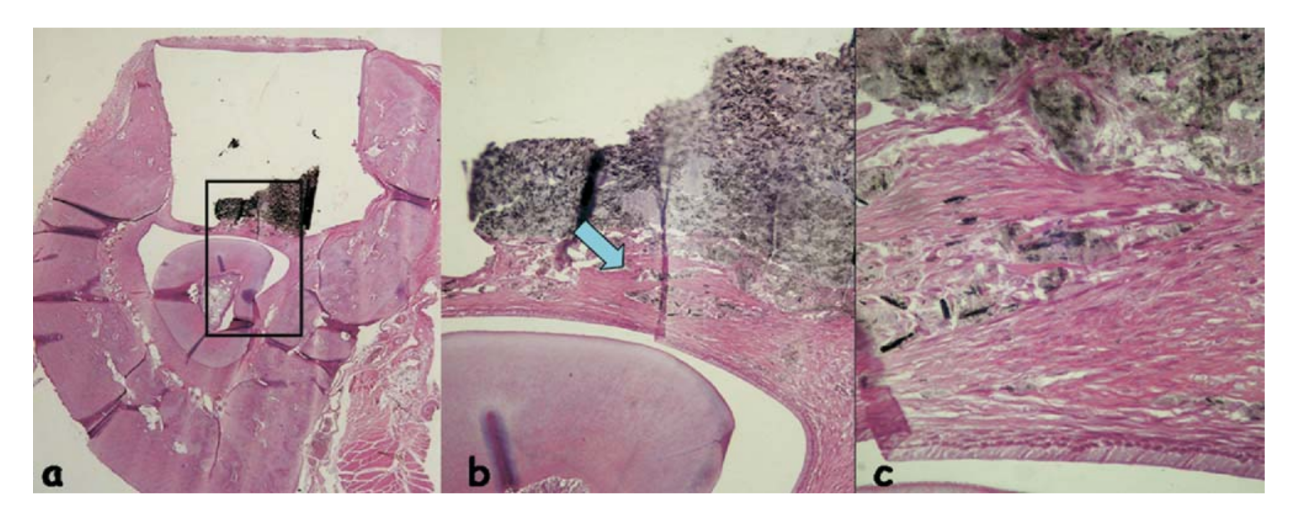

EndoREZ

The reaction was considered severe with an intense chronic inflammatory infiltrate, with the prevalence of lymphocytes, macrophages and giant foreign body cells (Fig. 3c). There were some dispersed material and the formation of a thick layer of connective tissue interposing between the material and bone (Fig. 3d).

and bone (outlined area in a) (H&E, original magnification 40x); (c) connective tissue with some dispersed material (green arrow in b) (H&E, original magnification 100x); (d) chronic inflammatory infiltrate and cells with fragments of the tested material (blue arrow in a) (H&E, original magnification 400x).

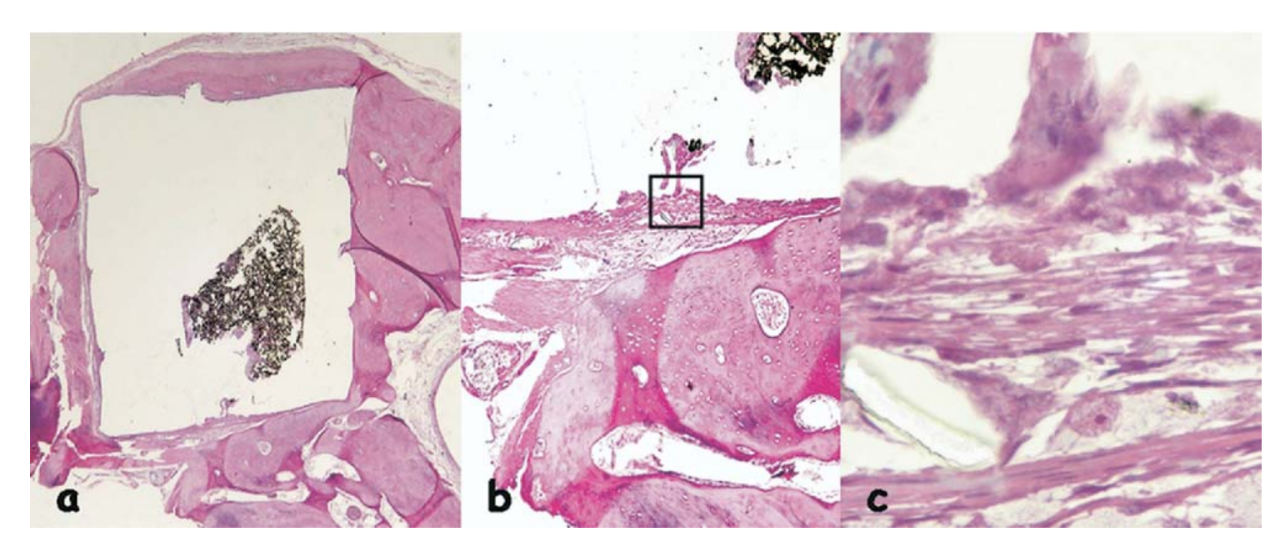

Epiphany

The inflammatory response was classified as none to slight. It was observed an organized connective tissue in close contact to the tested material (Fig. 5b), a few inflammatory cells and some dispersed material (Fig. 5c).

Twelve-Wk Observations

AH Plus

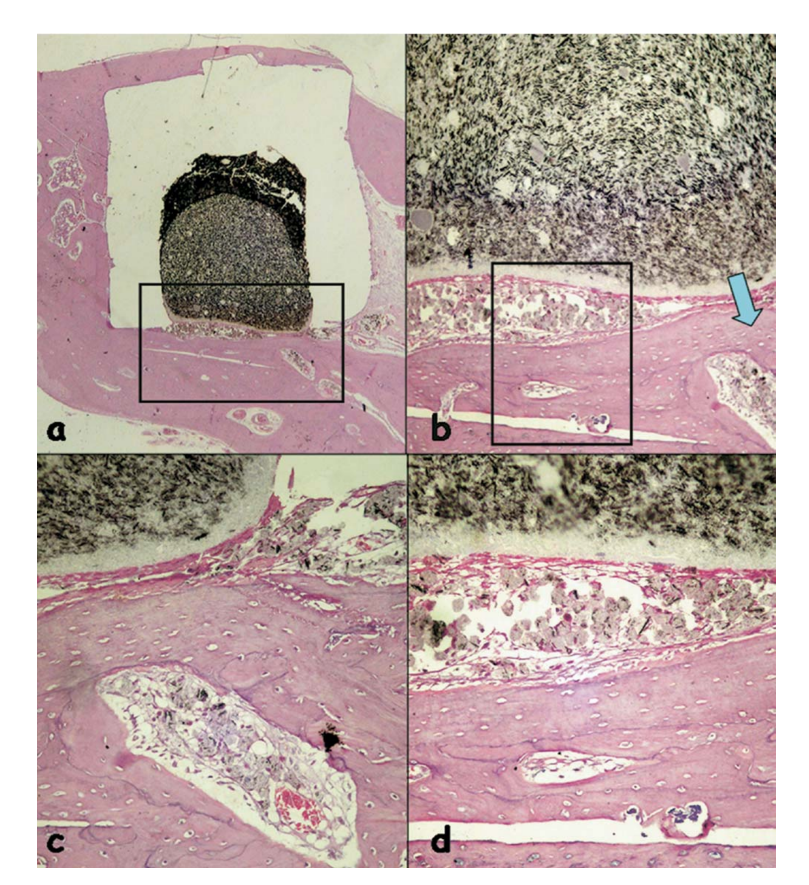

There was a chronic inflammatory reaction classified as moderate. It was observed the presence of some giant foreign body cells and thin layer of connective tissue interposed between the newly formed bone and the implanted material (Fig. 2c).

EndoREZ

The inflammatory reaction was still severe with an intense chronic inflammatory infiltrate, with the prevalence of lymphocytes, macrophages, and giant foreign body cells (Fig. 4b). It was observed the presence of some dispersed material, hemorrhagic areas, and hyperemic vessels (Fig. 4c).

Epiphany

The inflammatory reaction was classified as none to slight. It was observed the apposition of a neo-formed healthy bone close to the material (Fig. 6b) and a thin layer of connective tissue adjacent to the tested material without inflammatory cells (Fig. 6c, d).

(b) apposition of a newly formed healthy bone close to the material (outlined area in a) (H&E, original magnification 40x); (c) detail of the newly formed healthy

bone (blue arrow in b) (H&E, original magnification 100x); (d) thin layer of connective tissue juxtaposed to the tested material (outlined area in b) (H&E, original

magnification 200x).

Discussion

When a new material is introduced into the market, or an existing material is proposed for different application, its properties should be investigated and the results found compared to the results obtained by other investigators. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had responsibility for assessing and evaluating the biological effects of all drugs, materials, and devices used in human beings, including most dental products and devices. The FDA also provided for the recognition of standards established by private organizations, such as the ANSI/ADA. The revision of the first published Recommended Standard Practices for Biological Evaluation of Dental Materials was delayed to incorporate the essentials of FDA’s recommendations. This new document did not intended to discourage the industrial development of new and improved dental products by demanding overkill with biological tests. However, in this era of concern for chemical hazards, a toxicity profile on all new and improved materials should be developed to obtain relevant data on safety and efficacy. Even though no amount of experimental study can guarantee absolute safety for any substance, toxicological investigations provide data from which reasonable projections and predictions can be made about the conditions under which the agent can be safely used.

Although many tests as cytotoxicity, hemolysis, Ame’s test, Styles cell transformation, subcutaneous and bone implantations, sensitization, and endodontic usage test are listed for various levels of testing, they are not all required for each product. A judgment has to be made as to which tests are relevant. The initial tests are to provide a profile of toxicity in a biologic system, so that on a comparison basis the manufacturer will have a ball-park appreciation and realization of where his product lies. The FDA regulated devices fall under three classes, however, one of those that include the majority of dental devices and appliances would not be subject to standard-setting of premarket clearance. In other words, sometimes, even basic safety testing is not required before products can be promoted for clinical use.

The biocompatibility of dental materials is an important requirement because the toxic components present in these materials could produce irritation or even degeneration of the surrounding tissues, especially when accidentally extruded into the periradicular tissues.

Severe reactions have been reported after extrusion of some commonly used substances into the periradicular tissues. Overextended root canal sealers also represent chemical irritation, as virtually all endodontic sealers are highly toxic when freshly prepared. Furthermore, their irritating effect conceivably increases as the material/tissue contact surface area increases. Thus, the larger the volume of over-extended material, the larger the contact surface between sealer and the tissue, and the greater the intensity of chemical damage.

The implant test in guinea-pig bone tissue, as recommended by FDI, allows the testing of the material as it is utilized in the clinical setup. Although the results cannot be directly extrapolated to human beings, the test is standardized and direct comparison between materials can be established. The reactions alongside the cup external walls will reflect the trauma caused by the surgical procedures, necessary for the implantation. Teflon itself has been proven to cause only insignificant irritation of the tissues and it was used as the carrier because of its biocompatibility. Our results confirmed the absence of inflammatory reactions on the lateral wall of the carriers at both observation periods.

AH Plus, a two component paste root canal sealer, based on polymerization reaction of epoxy resin-amines, was tested for comparison. AH Plus sealer showed a severe reaction at 4-week observation period that diminished to moderate at 12 weeks (Figs. 1 and 2). The mechanism that may explain the inflammatory response regarding AH Plus sealer is the releasing of formaldehyde that has been shown to induce non-neoplastic responses, such as epithelial degeneration and a mixed inflammatory cell infiltration, besides allergic reaction and necrosis of the connective tissue. Another study has demonstrated that some sealers posed significant biological risks, particularly in freshly mixed condition. However, even after the setting period, toxicity may still exist. So, amines, present in AH Plus composition, which accelerate polymerization, could be also the reason for strong initial toxicity. Furthermore, inflammatory activity together with intact blood supply in the tissue repair process could eliminate initial toxicity of the material.

Recently, a new methacrylate-based endodontic sealer, EndoREZ was introduced as root canal sealer. EndoREZ is a hydrophilic, two-component, chemical-set material containing zinc oxide, barium sulfate, resins, and pigments in a matrix of urethane dimethacrylate resin. In the present study, EndoREZ caused severe inflammatory reaction at all experimental periods (Figs. 3 and 4). Using cultured cells, it was demonstrated that EndoREZ became more cytotoxic with time of exposure and presented significant cytotoxic risks when freshly mixed. The connective tissue reaction to silicone tubes filled with EndoRez implanted into the subcutaneous tissue of rats showed a severe reaction that significantly changed its profile after 30 days, with a moderate reaction after 3 months, and absence of inflammation at the fourth month observation period. Nevertheless, it was also reported that, in some animals, the inflammatory response persisted in all experimental periods. It was considered that after subcutaneous implantation of fresh EndoREZ, components such as zinc and barium were in direct contact with the tissue, and caused that severe initial reaction. In contrast to the results of the present research, Zmener et al. demonstrated a satisfactory bone tissue response at the 60-day observation period of EndoREZ implanted in the tibias of rats. The slow breakdown of EndoREZ sealer, illustrated by the dispersed material, and subsequent endocytosis by macrophages might have been the cause of such persistent chronic inflammation. Besides, root canal therapy performed with laterally condensed gutta-percha cones in conjunction with EndoRez seems to present an good overall success rate after 14 to 24 months recall evaluation.

In our study, AH Plus and EndoREZ showed no biocompatible characteristics because the reaction was severe in all periods and, according to FDI criteria, the material is considered unacceptable. Epiphany is a dual-curable dental resin-based composite sealer whose resin matrix is a mixture of bisphenol-A-glycidyl methacrylate, ethoxylate Bis-GMA, urethane dimetacrylate resin, and hydrophilic difunctional metacrylates. The results obtained in this work demonstrated optimal biological responses in both experimental periods for this material (Figs. 5 and 6). Recently, in an in vivo study, Epiphany was associated with less apical periodontitis. The authors correlated this finding to the superior resistance to coronal leakage of Epiphany, demonstrated in a previous work. However, Versiani et al., testing the solubility of Epiphany, demonstrated that it was higher than that established by ANSI/ADA Specification 57. The deionized distilled water used for the solubility test was submitted to the atomic absorption spectrometry and showed an extensive calcium release (41.46 mg/L). This high calcium release by Epiphany could explain the reduced apical periodontitis observed clinically and the results of the present work. Calcium ion release has showed to favor a more alkaline pH of the environment leading to biochemical effects that culminate in the acceleration of the repair process.

Conclusion

According to FDI criteria, the results obtained in this study allowed the conclusion that the Epiphany root canal sealer was the only material that presented intraosseous biocompatibility within the two analyzed periods.

Authors: Cássio J. A. Sousa, Cristiana R. M. Montes, Elizeu A. Pascon, Adriano M. Loyola, Marco A. Versiani

References:

- Sousa CJA, Loyola AM, Versiani MA, Biffi JCG, Oliveira RP, Pascon EA. A comparative histological evaluation of the biocompatibility of materials used in apical surgery. Int Endod J 2004;37:738 – 48.

- Siqueira JF Jr. Reaction of periradicular tissues to root canal treatment: benefits and drawbacks. Endod Topics 2005;10:123– 47.

- Nair PNR. Pathogenesis of apical periodontitis and the causes of endodontic failures. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2004;15:348 – 81.

- Spångberg L. Biological effects of root-canal-filling materials. Part 7. Reaction of bony tissue to implanted root-canal-filling material in guinea pigs. Odontol Tidsk 1969;77:133–59.

- Stanley HR. Toxicity testing of dental materials. United States: CRC Press, 1985.

- Zmener O, Banegas G, Pameijer CH. Bone tissue response to a methacrylate-based endodontic sealer: a histological and histometric study. J Endod 2005;31:457–9.

- Statement on posterior resin-based composites. ADA Council of Scientific Affairs: ADA Council on Dental Benefit Programs 1998;129:1627– 8.

- Tay FR, Loushine RJ, Weller RN, et al. Ultrastructural evaluation of the apical seal in roots filled with a polycaprolactone-based root canal filling material. J Endod 2005;31:514 –9.

- Boiullaguet S, Wataha JC, Lockwood PE, Galgano C, Golay A, Krejci I. Cytotoxicity and sealing properties of four classes of endodontic sealers evaluated by succinic dehydrogenase activity and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Eur J Oral Sci 2004;112:182–7.

- Louw NP, Pameijer CH, Norval G. Histopathological evaluation of a root canal sealer in subhuman primates [Abstract]. J Dent Res 2001;80:654

- Zmener O. Tissue response to a new methacrylate-based root canal sealer: preliminary observations in the subcutaneous connective tissue of rats. J Endod 2004;30:348 –51.

- Zmener O, Pameijer CH. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of a resin-based root canal sealer. Am J Dent 2004;17:19 –22.

- Shipper G, Teixeira FB, Arnold RR, Trope M. Periapical inflammation after coronal microbial inoculation of dog roots filled with gutta-percha or Resilon. J Endod 2005;31:91– 6.

- Bergenholtz G, Spångberg L. Controversies in endodontics. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2004;15:99 –114.

- Fédération Dentaire Internationale. Recommended standard practices for the biological evaluation of dental materials. Int Dent J 1980;30:174 – 6.

- Huang FM, Tsai CH, Yang SF, Chang YC. Induction of interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 gene expression by root canal sealers in human osteoblastic cells. J Endod 2005;31:679 – 83.

- Lindgren P, Eriksson K-F, Ringberg A. Severe facial ischemia after endodontic treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002;60:576 –9.

- Spångberg L, Pascon EA. The importance of material preparation for the expression of cytotoxicity during in vitro evaluation of biomaterials. J Endod 1988;14:247–50.

- Cohen BI, Pagnillo MK, Musikant BL, Dentsch AS. Evaluation of the release of formaldehyde for three endodontic filling materials. Oral Health 1998;88:37–9.

- Leonardo MR, de Silva LAB, Filho MT, de Silva RS. Release of formaldehyde by 4 endodontic sealers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1999;88:221–5.

- Morgan KT, Gross EA, Patterson DL. Distribution, progression, and recovery of acute formaldehyde-induced inhibition of nasal mucociliary function in F-344 rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1983;86:161–76.

- Kaplan AE, Ormaechea MF, Picca M, Canzobre MC, Ubios AM. Rheological properties and biocompatibility of endodontic sealers. Int Endod J 2003;36:527–32.

- Di Felice R, Lombardi T. Gingival and mandibular bone necrosis caused by a paraformaldehyde containing paste. Endod Dent Traumatol 1998;14:196 – 8.

- Matsumoto K, Inoue K, Matsumoto A. The effect of newly developed root canal sealers on rat dental pulp cells in primary culture. J Endod 1989;15:60 –7.

- Zmener O, Spielberg C, Lamberghini F, Rucci M. Sealing properties of a new epoxy resin-based root-canal sealer. Int Endod J 1997;30:332– 4.

- Miletić I, Devčić N, Anić I, Borčić J, Karlović Z, Osmak M. The cytotoxicity of Roeko-Seal and AH Plus compared during different setting periods. J Endod 2005;31:307–9.

- Zmener O, Pameijer CH. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of a resin-based root canal sealer. Am J Dent 2004;17:19 –22.

- Teixeira FB, Teixeira ECN, Thompson JY, Trope M. Fracture resistance of roots endodontically treated with a new resin filling material. J Am Dent Assoc 2004;135:646 –52.

- Shipper G, Trope M. In vitro microbial leakage of endodontically treated teeth using new and standard obturation techniques. J Endod 2004;30:154 – 8.

- Versiani MA, Carvalho-Júnior JR, Sasaki E, et al. A comparative study of physicochemical properties of AH Plus™ and Epiphany™ root canal sealers. Int Endod J (in press).

- ANSI/ADA Specification No. 57. Endodontic Sealing Material. Washington: USA. 2000.

- Seux D, Couble ML, Hartmann DJ, Gauthier JP, Magloire H. Odontoblast-like cytodifferentiation of human dental pulp ‘in vitro’ in the presence of a calcium hydroxide-containing cement. Arch Oral Biol 1991;36:117–28.