Impact of needle insertion depth on the removal of hard-tissue debris

Abstract

Aim: To evaluate the effect of depth of insertion of an irrigation needle tip on the removal of hard-tissue debris using micro-computed tomographic (micro-CT) imaging.

Methodology: Twenty isthmus-containing mesial roots of mandibular molars were anatomically matched based on similar morphological dimensions using micro-CT evaluation and assigned to two groups (n = 10), according to the depth of the irrigation needle tip during biomechanical preparation: 1 or 5 mm short of the working length (WL). The preparation was performed with Reciproc R25 file (tip size 25, .08 taper) and 5.25% NaOCl as irrigant. The final rinse was 17% EDTA followed by bidistilled water. Then, specimens were scanned again, and the matched images of the canals, before and after preparation, were examined to quantify the amount of hard-tissue debris, expressed as the percentage volume of the initial root canal volume. Data were compared statistically using the Mann–Whitney U-test.

Results: None of the tested needle insertion depths yielded root canals completely free from hard-tissue debris. The insertion depth exerted a significant influence on debris removal, with a significant reduction in the percentage volume of hard-tissue debris when the needle was inserted 1 mm short of the WL (P < 0.05).

Conclusions: The insertion depth of irrigation needles significantly influenced the removal of hard-tissue debris. A needle tip positioned 1 mm short of the WL resulted in percentage levels of hard-tissue debris removal almost three times higher than when positioned 5 mm from the WL.

Introduction

An important step for successful root canal treatment is the removal of organic and inorganic debris that, in an infected root canal system, may contain bacteria and serve as a nidus for reinfection (Versiani et al. 2016). This goal can be achieved by the combination of mechanical preparation with chemical irrigation to control or eliminate the causative agents of apical periodontitis (Kahn et al. 1995, Lee et al. 2004). However, large areas of untouched canal walls (Peters et al. 2001) and accumulation of hard-tissue debris in fins, isthmuses, irregularities and ramifications have been reported by several authors as an undesirable effect of mechanical preparation (Paqué et al. 2009, De-Deus et al. 2015, Versiani et al. 2016). Therefore, thorough irrigation of the root canal system is of utmost importance to remove infected debris (Haapasalo et al. 2010, Boutsioukiset al. 2014).

The main limitation of current irrigation techniques is the difficulty of spreading and flushing the solution in limited and narrow anatomical structures of the root canal system such as isthmuses or fins (Versiani et al. 2015). The effectiveness of the fluid dynamics of the irrigating solution during chemomechanical preparation relies on many variables, such as canal anatomy, the delivery system, volume, flow and type of irrigation agent, as well as the type and diameter of the irrigation needle (Abou-Rass & Piccinino 1982,Kahn et al. 1995). Despite extensive research on irrigation and agitation techniques, the conventional syringe and needle is still the most commonly used irrigation method (Shen et al. 2010, Thomas et al. 2014). In this technique, replenishment and exchange of irrigants depend upon the depth of needle, which may also affect the removal of accumulated hard-tissue debris (Abou-Rass & Piccinino 1982,Chow 1983, Albrecht et al. 2004, Sedgley et al. 2005, Hsieh et al. 2007). However, it remains uncertain which should be the ideal needle penetration depth to achieve a safe and effective debridement strategy and to establish evidence-based guidelines for root canal irrigation.

Recently, several authors have focused on the study of accumulated hard-tissue debris in recesses, isthmuses, irregularities and ramifications using micro-computed tomographic (micro-CT) imaging (Paqué et al. 2009, 2011, 2012, Robinson et al.

2013, De-Deus et al. 2015, Versiani et al. 2016); however, none of them evaluated the effect of the insertion depth of the needle tip on the removal of hard-tissue debris. Hence, the present study was designed to assess the effect of the position of the irrigation needle tip on the removal of hard-tissue debris in mesial root canals of mandibular molars using micro-CT. Micro-CT imaging allows monitoring the accumulation and removal of radiopaque structures in the main space of the root canal and its recesses and isthmuses during and after instrumentation (Robinson et al. 2012, De-Deus et al. 2014, 2015) whilst preserving sample integrity. The hypothesis tested was that the insertion depth of the irrigation needle tip does not have a significant impact on the removal of hard-tissue debris.

Materials and methods

Sample size estimation

An a priori Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was selected from the t-tests family in G*Power 3.1 software for Mac (Heinrich Heine, Universität Düsseldorf). Based on data from a previous study evaluating hard-tissue debris accumulation after irrigation procedures (Versiani et al. 2016), the effect size for this study was established (=1.87). An alpha-type error of 0.05, power beta of 0.95 and allocation ratio N2/N1 of 1 were also specified. A total of 18 samples (nine per group) were indicated as the ideal size required for observing significant differences.

Specimen selection

This study was revised and approved by the Ethics Committee, Nucleus of Collective Health Studies (protocol n° 2223 – CEP/HUPE). One-hundred and six human mandibular first and second molars with moderately curved mesial roots (10–20°) were selected from a pool of extracted teeth and stored in a 0.1% thymol solution at 5 °C. Digital radiographs taken in a buccolingual direction were used to calculate the angle of the curvature using AxioVision 4.5 software (Carl Zeiss Vision GmbH, Hallbergmoos, Germany), according to Schneider’s method (Schneider 1971).

The teeth were pre-scanned in a micro-CT device (SkyScan 1173; Bruker micro-CT, Kontich, Belgium) using an isotropic resolution of 70 lm at 70 kV and 114 mA to obtain a pre-treatment outline of the root canals. Following Fan et al. (2010), 20 specimens with mesial roots with isthmuses type I (narrow sheet and complete connection existing between two canals) or III (incomplete isthmus existing above or below a complete isthmus) were selected. Then, the specimens were scanned again at an increased isotropic resolution of 14.16 lm through 360° rotation around the vertical axis with a rotation step of 0.5°, camera exposure time of 7000 milliseconds and frame averaging of 5, using a 1.0-mm-thick aluminium filter. The acquired images were reconstructed into cross-sectional slices with NRecon v.1.6.9 software (Bruker micro-CT) using standardized parameters for beam hardening (40%), ring artefact correction (10) and similar contrast limits. The volume of interest was selected to extend from the furcation level to the apex of the root, resulting in the acquisition of 700–800 transverse cross sections per tooth.

Subsequently, mesial roots were matched to create two groups of 10 roots each based on the root canal configuration, three-dimensional (3D) morphologic aspects of the canals (volume and surface area), degree of curvature and root length. One root from each group was randomly assigned to one of the two groups (n = 10) according to the insertion depth of the irrigation needle: 1 or 5 mm short of the working length (WL). After checking for normality assumption (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity (Levene’s test) of the groups with respect to root canal volume and surface area, degree of curvature and root length, anatomical matching between groups was statistically confirmed (P > 0.05; independent samples t-test).

Root canal preparation

A single experienced operator performed all procedures. After access cavity preparation, the WL was determined by passing a size 10 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) through the major foramen and withdrawing it 1.0 mm. Next, the apical foramen of each root was sealed with hot glue and embedded in polyvinyl siloxane to create a closed-ended system (Susin et al. 2010). A glide path was established by scouting a stainless steel size 15 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer) up to the WL. Then, root canals were prepared with Reciproc R25 file size 25, .08 taper (VDW, Munich, Germany), powered by an electric motor (VDW Silver motor; VDW) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each instrument was used to enlarge four root canals, and four waves of instrumentation were performed to prepare each root canal. The WL was reached in the fourth wave for all canals.

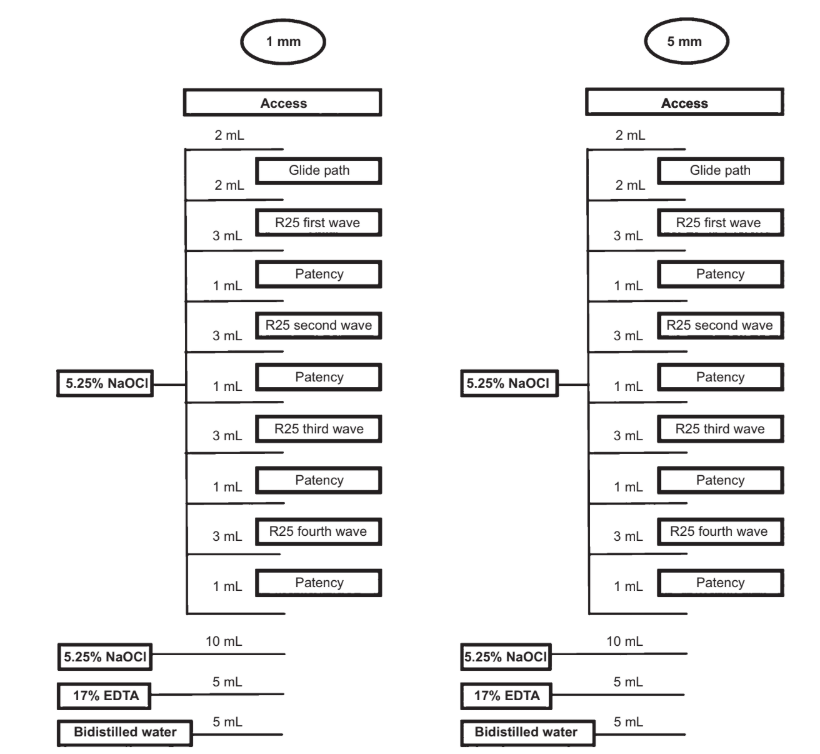

Throughout the biomechanical preparation, a total of 30 mL 5.25% NaOCl was delivered at a flow rate of 2 mL min—1 by a VATEA peristaltic pump (ReDent-Nova, Ra’anana, Israel) connected to a 30-gauge side-vented needle (Maxi-Probe; Dentsply Rinn, Elgin, IL, USA) placed without binding up to 1 or 5 mm short of the WL, according to each group. Each root canal was irrigated with 2 mL NaOCl after access and glide path procedures, respectively. Then, 3 mL NaOCl was used after each wave of instrumentation and 1 mL NaOCl after patency. After preparation, an additional rinse with 10 mL NaOCl was performed, followed by 5 mL 17% EDTA (pH = 7.7) delivered at a flow rate of 1 mL min—1 for 5 min. Finally, a 5-min 5-mL rinse with bidistilled water was used in the final irrigation to flush out the EDTA.

Thus, the overall volume of irrigant solutions per canal was 40 mL, in a total time of 25 min (Fig. 1). Irrigant aspiration was performed at the level of root canal orifices with a SurgiTip (Ultradent Products Inc., South Jordan, UT, USA) attached to a high-speed suction pump. Then, canals were dried with absorbent paper points (Dentsply Maillefer), imaged again with a micro-CT system and reconstructed with the same parameters used in pre-treatment scans.

Quantitative three-dimensional analysis

The image stacks of the specimens after preparation were rendered and co-registered with their respective preoperative data sets using an affine algorithm of the 3D Slicer 4.4.0 software (available from http://www.slicer.org) (Fedorov et al. 2012). Matched images of the canals were examined to calculate volume using the ImageJ software v.1.49 (Schneideret al. 2012). Then, quantification of hard-tissue debris was undertaken as described previously (Neves et al. 2014) and expressed as the percentage volume of the initial root canal volume for each specimen. Debris was considered as the material with density similar to dentine in regions previously occupied by air in the nonprepared root canal space and quantified by inter- section between images before and after canal instrumentation (Robinson et al. 2012, De-Deus et al. 2014). Subsequently, colour-coded pre- and postoperative root canal models and debris were rendered and qualitatively evaluated using the plugins 3D Viewer and 3D Object Counter, respectively, in the ImageJ software (Schmid et al. 2010, Schneider et al. 2012).

Statistical analysis

Data regarding the accumulated hard-tissue debris created after root canal preparation were calculated as the percentage volume of the initial root canal volume and input for statistics. Data were skewed (Shapiro-Wilk test) and, therefore, compared using Mann–Whitney U-test, with the alpha-type error set at 0.05.

Results

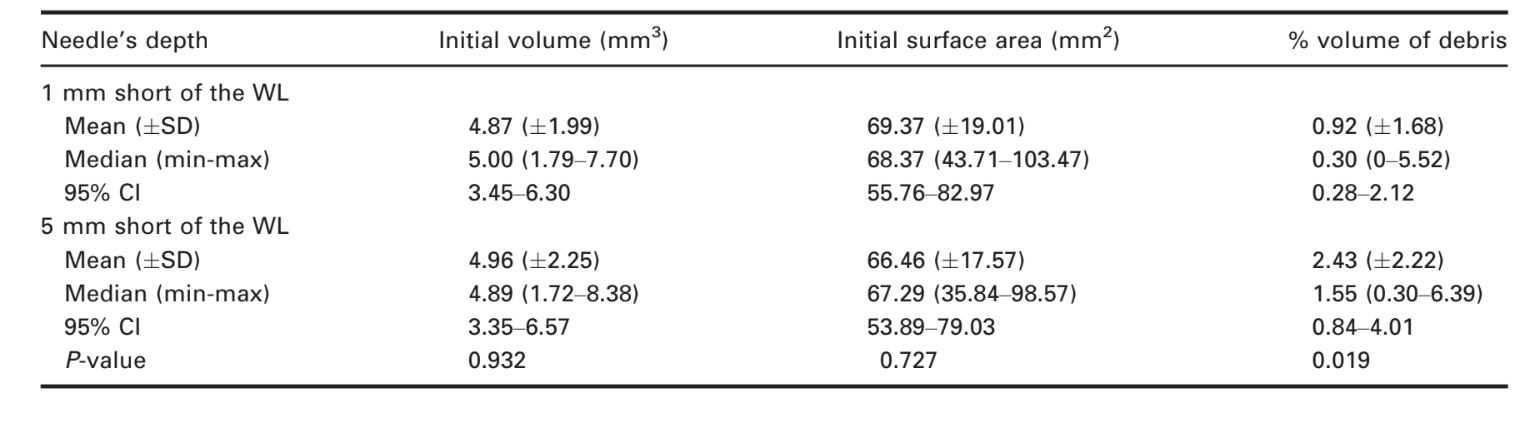

Irrigation of the root canals using the needle tip 1 mm short of the WL left a mean of 0.92% (± 1.68) of the total root canal system volume filled with accumulated hard-tissue debris. On the other hand, after irrigation using the needle tip 5 mm short of the WL, 2.43% (± 2.22) of the total canal volume was filled with accumulated hard-tissue debris. The difference between the groups was significant (Mann–Whitney U-test, P = 0.019) (Table 1).

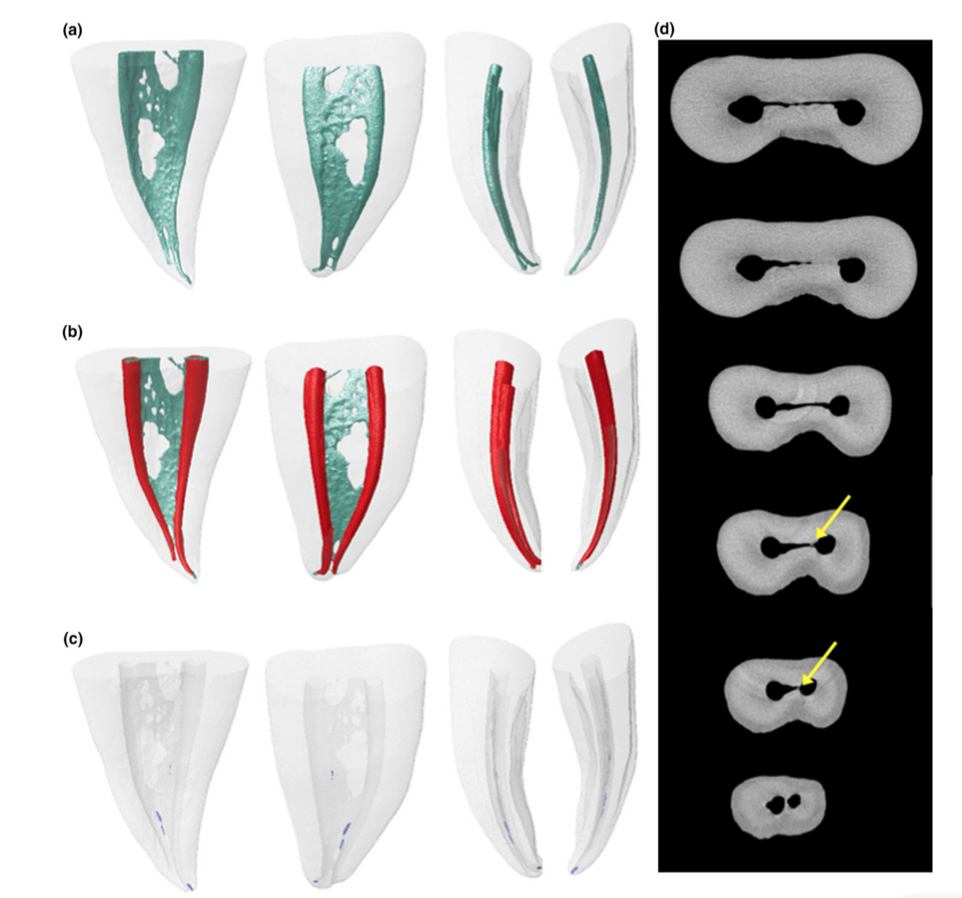

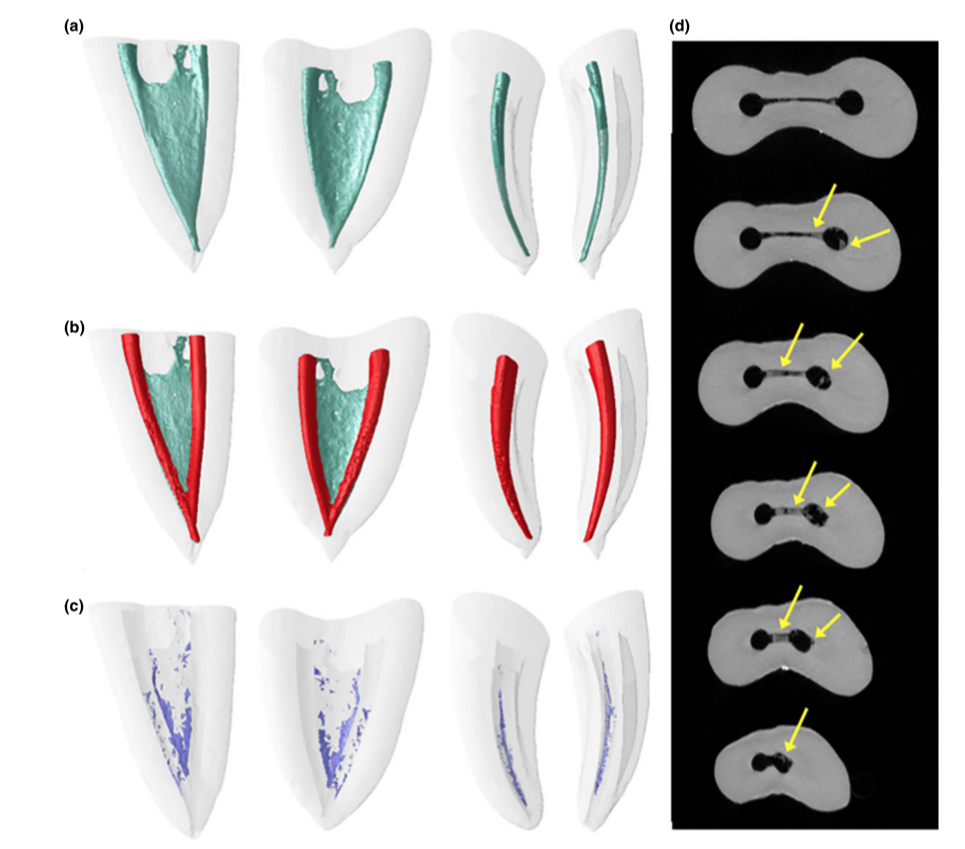

Representative 3D models and cross-sectional slices in Figs 2 and 3 show the distribution of the accumulated hard-tissue debris after root canal preparation irrigated with the needle tip positioned at 1 or 5 mm short of the WL in mesial roots of mandibular molars.

Discussion

It was hypothesized that dentine particles cut from the canal walls by rotary instruments were actively packed into soft-tissue remnants within the root canal space and became more resistant to removal by conventional syringe-and-needle irrigation (Paqué et al. 2009, 2012, Endal et al. 2011). This packed debris may potentially interfere with disinfection by preventing irrigant flow and neutralizing the antibacterial effects of the irrigating solution (Paqué et al. 2012). Therefore, debris generated during mechanical preparation must be removed by the flushing of the irrigant solution. However, it has been demonstrated that several factors may affect the efficiency of irrigation during chemomechanical preparation (Abou-Rass & Piccinino 1982). In the present study, the insertion depth of the irrigation needle was chosen as an independent variable to be tested on the reduction of accumulated hard-tissue debris, considering the lack of information on this subject in the literature, using a micro-CT methodological approach. Additionally, mesial roots of mandibular molars were selected because of the high incidence of isthmuses in comparison with roots from other teeth groups (Weller et al. 1995, Mannocci et al. 2005, Harris et al. 2013), which makes their debridement a laborious challenge. Several authors have advocated that irrigation procedures must provide an effective debridement of the root canal space (Chow 1983, Sedgley et al. 2005, Hsieh et al. 2007, Boutsioukis et al. 2010); however, the literature has limited information associating needle insertion depth and debris removal. Earlier studies using destructive methodological approaches reported that the proximity of the irrigation needle to the apex played an important role in the removal of debris (Brown & Doran 1975, Abou-Rass & Piccinino 1982,Chow 1983). Similarly, Sedgley et al. (2005) showed that needle depth had a significant effect on mechanical removal of bacteria from within the root canal space. A previous computational fluid dynamics study evaluating the effect of needle insertion depth on irrigant flow recommended that side-vented needles should be positioned within 1 mm to the WL if possible because the irrigant replacement reached the WL only when the side-vented needle was placed at this position (Boutsioukis et al. 2010).

More recently, several studies evaluating the accumulation of hard-tissue debris in recesses, isthmuses, irregularities and ramifications using micro-CT have been published (Paqué et al. 2009, 2011, 2012, Robinson et al. 2013, De-Deus et al. 2015, Versiani et al. 2016). This technology quantified the accumulation and removal of radiopaque debris in various areas of the root canal system (Robinson et al. 2012, De-Deus et al. 2014, 2015). This is a nondestructive technology that enables the same specimens to be assessed after different treatment steps to observe both quantitatively and qualitatively hard-tissue debris. A disadvantage of this method is that it is not possible to analyse remaining soft tissue (Paqué et al. 2009). Overall, previous micro-CT studies revealed that sequential or supplementary irrigation procedures during or after root canal preparation resulted in less hard-tissue debris in isthmus-containing root canal systems, which is in accordance with the present results. In this study, a significant reduction in the volume of hard-tissue debris was observed when the needle tip was placed 1 mm short of the WL, thus rejecting the tested hypothesis. In contrast, root canals in which the needle was 5 mm short of the WL exhibited almost a three-fold increase in the percentage volume of debris. However, both irrigation protocols did not succeeded in rendering mesial root canal systems free from hard-tissue debris. Thus, in conventional syringe–needle irrigation, optimization of the irrigation process can be related to the depth of needle penetration (Siu & Baumgartner 2010).

In the current study, a 30-G side-vented needle was used in both groups. This needle has a lumen on the lateral surface located 2 mm from the blunt tip and produces lower apical pressure than an open-end needle (Boutsioukis et al. 2007); however, its closed end is important to avoid inadvertent displacement of NaOCl into the periapical tissues. Although the irrigating solution used with conventional open-end syringe–needle technique does not reach more than 1 mm apically from the needle tip (Ram 1977), it has been reported that 42% of endodontists in North American had at least one accident with NaOCl extrusion (Kleier et al. 2008). Consequently, the deeper the needle penetration, the higher is the risk of irrigant extrusion (Psimma et al. 2013). This long-standing background explains why some professionals avoid reaching the WL whilst irrigating with NaOCl solution. The use of a penetration depth far from the WL may be protective against apical extrusion, how- ever, according to the present results, this will result in a significantly greater amount of remaining hard-tissue debris in isthmus-containing mesial roots of mandibular molars.

To help disseminate the concept of close-to-WL irrigation as demonstrated by the present study, it is important to avoid incidents with NaOCl solution, such as using low flow rate and pressure of irrigant delivery and preventing the binding of the needle to the canal walls, as it can act like a piston, forcing the solution beyond the apex. Moreover, the use of a side-vented type irrigation needle allows an upward turbulent motion around and beyond the end of the probe, which thoroughly irrigates the root canal system and prevents solution and debris from being extruded through the apical foramen (Kahn et al. 1995, Sainiet al. 2013).

Conclusions

Neither irrigation approach succeeded in rendering the isthmus-containing mesial root canal system free from accumulated hard-tissue debris; however, the depth of needle insertion significantly influenced the removal of hard-tissue debris. The needle tip positioned 1 mm short of the WL resulted in percentage levels of hard-tissue debris removal almost three times higher than when positioned at the 5 mm level. Within the conditions of this study, it may be concluded that the closer the needle is to the WL, the more efficient is the removal of hard-tissue debris. This outcome emphasizes that the choice of an adequate needle positioned at an appropriate level is an important step to optimize the overall quality of the irrigation procedure.

Authors: R. Perez, A. A. Neves, F. G. Belladonna, E. J. N. L. Silva, E. M. Souza, S. Fidel, M. A. Versiani, I. Lima, C. Carvalho, G. De-Deus

References:

- Abou-Rass M, Piccinino MV (1982) The effectiveness of four clinical irrigation methods on the removal of root canal debris. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Endodontics 54, 323–8.

- Albrecht LJ, Baumgartner JC, Marshall JG (2004) Evaluation of apical debris removal using various sizes and tapers of ProFile GT files. Journal of Endodontics 30, 425–8.

- Boutsioukis C, Lambrianidis T, Kastrinakis E, Bekiaroglou P (2007) Measurement of pressure and flow rates during irrigation of a root canal ex vivo with three endodontic needles. International Endodontic Journal 40, 504–13.

- Boutsioukis C, Lambrianidis T, Verhaagen B et al. (2010) The effect of needle-insertion depth on the irrigant flow in the root canal: evaluation using an unsteady computational fluid dynamics model. Journal of Endodontics 36, 1664–8.

- Boutsioukis C, Psimma Z, Kastrinakis E (2014) The effect of flow rate and agitation technique on irrigant extrusion ex vivo. International Endodontic Journal 47, 487–96.

- Brown JI, Doran JE (1975) An in vitro evaluation of the particle flotation capability of various irrigating solutions. Journal of the California Dental Association 3, 60–3.

- Chow TW (1983) Mechanical effectiveness of root canal irrigation. Journal of Endodontics 9, 475–9.

- De-Deus G, Marins J, Neves Ade A et al. (2014) Assessing accumulated hard-tissue debris using micro-computed tomography and free software for image processing and analysis. Journal of Endodontics 40, 271–6.

- De-Deus G, Marins J, Silva EJ et al. (2015) Accumulated hard-tissue debris produced during reciprocating and rotary nickel-titanium canal preparation. Journal of Endodontics 41, 676–81.

- Endal U, Shen Y, Knut A, Gao Y, Haapasalo M (2011) A high-resolution computed tomographic study of changes in root canal isthmus area by instrumentation and root filling. Journal of Endodontics 37, 223–7.

- Fan B, Pan Y, Gao Y, Fang F, Wu Q, Gutmann JL (2010) Three-dimensional morphologic analysis of isthmuses in the mesial roots of mandibular molars. Journal of Endodontics 36, 1866–9.

- Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J et al. (2012) 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 30, 1323–41.

- Haapasalo M, Shen Y, Qian W, Gao Y (2010) Irrigation in endodontics. Dental Clinics of North America 54, 291–312.

- Harris SP, Bowles WR, Fok A, McClanahan SB (2013) An anatomic investigation of the mandibular first molar using micro-computed tomography. Journal of Endodontics 39, 1374–8.

- Hsieh YD, Gau CH, Kung Wu SF, Shen EC, Hsu PW, Fu E (2007) Dynamic recording of irrigating fluid distribution in root canals using thermal image analysis. International Endodontic Journal 40, 11–7.

- Kahn FH, Rosenberg PA, Gliksberg J (1995) An in vitro evaluation of the irrigating characteristics of ultrasonic and subsonic handpieces and irrigating needles and probes. Journal of Endodontics 21, 277–80.

- Kleier DJ, Averbach RE, Mehdipour O (2008) The sodium hypochlorite accident: experience of diplomates of the American Board of Endodontics. Journal of Endodontics 34, 1346–50.

- Lee SJ, Wu MK, Wesselink PR (2004) The effectiveness of syringe irrigation and ultrasonics to remove debris from simulated irregularities within prepared root canal walls. International Endodontic Journal 37, 672–8.

- Mannocci F, Peru M, Sherriff M, Cook R, Pitt Ford TR (2005) The isthmuses of the mesial root of mandibular molars a micro-computed tomographic study. International Endodontic Journal 38, 558–63.

- Neves AA, Silva EJ, Roter JM et al. (2014) Exploiting the potential of free software to evaluate root canal biomechanical preparation outcomes through micro-CT images. International Endodontic Journal 48, 1033–42.

- Paqué F, Laib A, Gautschi H, Zehnder M (2009) Hard-tissue debris accumulation analysis by high-resolution computed tomography scans. Journal of Endodontics 35, 1044–7.

- Paqué F, Boessler C, Zehnder M (2011) Accumulated hard tissue debris levels in mesial roots of mandibular molars after sequential irrigation steps. International Endodontic Journal 44, 148–53.

- Paqué F, Rechenberg DK, Zehnder M (2012) Reduction of hard-tissue debris accumulation during rotary root canal instrumentation by etidronic acid in a sodium hypochlorite irrigant. Journal of Endodontics 38, 692–5.

- Peters OA, Scho€nenberger K, Laib A (2001) Effects of four Ni-Ti preparation techniques on root canal geometry assessed by micro computed tomography. International Endodontic Journal 34, 221–30.

- Psimma Z, Boutsioukis C, Kastrinakis E, Vasiliadis L (2013) Effect of needle insertion depth and root canal curvature on irrigant extrusion ex vivo. Journal of Endodontics 39, 521–4.

- Ram Z (1977) Effectiveness of root canal irrigation. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Endodontics 44, 306–12.

- Robinson JP, Lumley PJ, Claridge E et al. (2012) An analytical micro CT methodology for quantifying inorganic dentin debris following internal tooth preparation. Journal of Dentistry 40, 999–1005.

- Robinson JP, Lumley PJ, Cooper PR, Grover LM, Walmsley AD (2013) Reciprocating root canal technique induces greater debris accumulation than a continuous rotary technique as assessed by 3-dimensional micro-computed tomography. Journal of Endodontics 39, 1067–70.

- Saini M, Kumari M, Taneja S (2013) Comparative evaluation of the efficacy of three different irrigation devices in removal of debris from root canal at two different levels: an in vitro study. Journal of Conservative Dentistry 16, 509–13.

- Schmid B, Schindelin J, Cardona A, Longair M, Heisenberg M (2010) A high-level 3D visualization API for Java and ImageJ. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 274.

- Schneider SW (1971) A comparison of canal preparations in straight and curved root canals. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Endodontics 32, 271–5.

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 9, 671–5.

- Sedgley CM, Nagel AC, Hall D, Applegate B (2005) Influence of irrigant needle depth in removing bioluminescent bacteria inoculated into instrumented root canals using real-time imaging in vitro. International Endodontic Journal 38, 97–104.

- Shen Y, Gao Y, Qian W et al. (2010) Three-dimensional numeric simulation of root canal irrigant flow with different irrigation needles. Journal of Endodontics 36, 884–9.

- Siu C, Baumgartner JC (2010) Comparison of the debridement efficacy of the EndoVac irrigation system and conventional needle root canal irrigation in vivo. Journal of Endodontics 36, 1782–5.

- Susin L, Liu Y, Yoon JC et al. (2010) Canal and isthmus debridement efficacies of two irrigant agitation techniques in a closed system. International Endodontic Journal 43, 1077–90.

- Thomas AR, Velmurugan N, Smita S, Jothilatha S (2014) Comparative evaluation of canal isthmus debridement efficacy of modified EndoVac technique with different irrigation systems. Journal of Endodontics 40, 1676–80.

- Versiani MA, De-Deus G, Vera J et al. (2015) 3D mapping of the irrigated areas of the root canal space using micro-computed tomography. Clinical Oral Investigations 19, 859–66.

- Versiani MA, Alves FR, Andrade-Junior CV et al. (2016) Micro-CT evaluation of the efficacy of hard-tissue removal from the root canal and isthmus area by positive and negative pressure irrigation systems. International Endodontic Journal doi: 10.1111/iej.12559 [Epub ahead of print].

- Weller RN, Niemczyk SP, Kim S (1995) Incidence and position of the canal isthmus. Part 1. Mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar. Journal of Endodontics 21, 380–3.