Root Canal Preparation Does Not Induce Dentinal Microcracks In Vivo

Abstract

Introduction: This in vivo study aimed to evaluate the development of dentinal microcracks after root canal preparation of contralateral premolars with rotary or hand instruments using micro–computed tomographic technology.

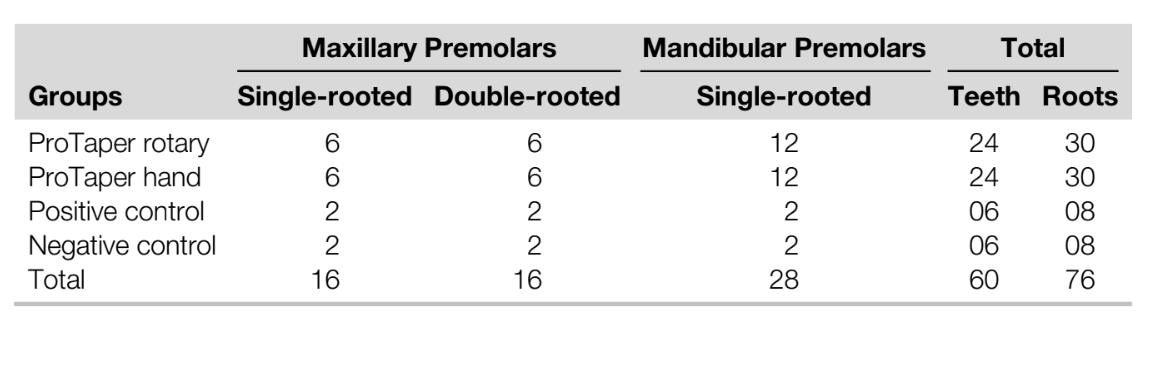

Methods: Sixty contralateral intact maxillary and mandibular premolars in which extraction was indicated for orthodontic purposes were selected and distributed into positive (n = 6, teeth with induced root microcracks) and negative (n = 6, intact teeth) control groups as well as 2 experimental groups (n = 24) according to the instrumentation protocol: ProTaper rotary (PTR) or ProTaper hand (PTH) systems (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland). After root canal preparation, teeth were extracted using an atraumatic technique and scanned at a resolution of 17.18 mm. A total of 43,361 cross-sectional images of the roots were screened for the presence of dentinal microcracks. The results were expressed as the percentage and number of root section images with microcracks for each group.

Results: All roots in the positive control group showed microcracks at the apical third, whereas no cracks were observed in the specimens of the negative control group. In the PTR group, 17,114 cross-sectional images were analyzed, and no microcrack was observed. In the PTH group, dentinal microcracks were observed in 116 of 17,408 cross-sectional slices (0.66%) of only 1 specimen. These incomplete microcracks extended from the external root surface into the inner root dentin at the area of reduced dentin thickness.

Conclusions: Root canal instrumentation with PTR and PTH instruments of contralateral maxillary and mandibular premolars did not result in the formation of dentinal microcracks in vivo. (J Endod 2019;45:1258–1264.)

Vertical root fracture (VRF) is 1 of the complications after root canal treatment that results in a poor prognosis of the root-filled teeth. Although several iatrogenic and noniatrogenic factors have been suggested to contribute to the occurrence of VRF, there has been a growing interest in the effect of the root canal treatment procedure as a risk factor that may increase the predisposition of endodontically treated teeth to fracture. Iatrogenic steps that contribute to dentin removal and/or increased wedging forces that exceeded the binding strength of dentin may result in root dentinal microcracks. Thus, root canal instrumentation may be a risk factor that leads to the formation of incomplete root dentinal cracks, which may progress under the influence of chewing forces to result in VRF.

Root canal shaping is an integral step in root canal treatment, which facilitates mechanical debridement and creates an optimal shape for adequate root canal irrigation, medicament delivery, and root filling. Many studies have implicated that crack or defect formation in root dentin can be caused by root canal instrumentation and obturation procedures per se. Others have highlighted that apical root dentinal microcracks may arise after root canal instrumentation at the apical foramen or beyond. Conversely, nondestructive evaluations by micro–computed tomographic (micro-CT) imaging have concluded that root canal preparation may not result in the formation of new dentinal microcracks and that dentin defects/ microcracks observed after preparation were preexisting cracks. A recent publication using cadaveric bone–block models concluded that microcracks observed in stored extracted teeth could be a result of extraction forces or storage conditions rather than a preexisting condition.

Most research on root canal instrumentation–derived dentinal microcracks has been performed under in vitro conditions with extracted teeth without standardization of age and pre-extraction conditions. More recently, in situ studies have also been conducted using a human cadaver model and a pig jaw model. However, in vivo evaluation is imperative in order to investigate the results of orthograde root canal instrumentation on dentinal microcrack formation in human teeth, while teeth remained in the oral environment supported by the periodontium. The presence of vital periodontal tissues is critical because it links teeth to the surrounding alveolar bone and aids in distributing forces to supporting bone. The purpose of this in vivo study was to evaluate the development of dentinal microcracks after root canal preparation of contralateral premolars using rotary and hand ProTaper Universal instruments (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) by means of micro-CT technology. The null hypothesis tested was that root canal instrumentation does not result in the formation of root dentinal microcracks in vivo. This study would provide clinically pertinent information on the probability of the occurrence of instrumentation-derived microcracks in root dentin.

Materials and methods

The study protocol was approved by the university ethical review board and registered in the national clinical trials registry (CTRI/ 2018/03/012519). Patients who required extraction of contralateral maxillary and mandibular first premolars for orthodontic treatment purposes were assessed. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient who agreed to participate (15–30 years old, healthy, nonmedicated human donors) after the methodology and purpose of the study were explained. The inclusion criteria were as follows: only intact vital premolar teeth presenting with relatively straight root canals (˂20˚curvature) and a fully formed apex without caries, restoration, previous root canal treatment, traumatic occlusion, or periodontal/ periapical disease. Based on these criteria, 60 contralateral premolar pairs (N = 60, 76 roots), including 16 double-rooted maxillary premolars, 16 single-rooted maxillary premolars, and 28 single-rooted mandibular premolars, were selected. All maxillary premolars (32 teeth) had 2 root canals (64 canals), whereas mandibular premolars (28 teeth and 28 canals) had 1 root canal each (Table 1).

Sample Size Calculation

The ideal sample size for this in vivo study on microcrack formation was calculated from the results of a previous study. The sample size was calculated using G power v.3.1.9.2 for Windows (University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) based on the proportional difference formula with an alpha-type error of 0.05 and a power beta of 0.95. The estimated sample size was 21 teeth per group.

Root Canal Preparation and Groups After local anesthesia and rubber dam isolation, access cavities were prepared using a round bur (Mani Inc, Tokyo, Japan) in a high-speed handpiece. The working length (WL) was established with an electronic apex locator (Dentaport ZX; J Morita, Tokyo, Japan) and radiographically verified with a stainless steel (SS) size 10 K-file (Mani Inc, Tokyo, Japan). A glide path was prepared with a SS size 15 K-file (Mani Inc). Contralateral premolars were randomly assigned to 2 experimental (n = 24) and 2 control (n = 6) groups in a split-mouth design using a coin toss method. This resulted in an equal and random distribution of tooth types. Canal preparation was performed according to the manufacturer’s directions as follows:

- The ProTaper rotary group (PTR, n = 24): in maxillary premolars (n = 12), rotary preparation was performed in both canals using S1 and S2 followed by F1, F2, and F3 instruments up to the WL. A similar protocol was followed in mandibular premolars (n = 12), and further apical enlargement was performed with F4 and F5 instruments. An X-Smart endodontic motor (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) was used with a specific torque and velocity for each instrument in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, and the instrumentation was performed with in- and-out strokes in an apical direction.

- The ProTaper hand group (PTH, n = 24): in maxillary premolars (n = 12), hand preparation was performed in both canals using a crown-down modified balanced force technique with S1 and S2 followed by F1, F2, and F3 manual instruments up to the WL without apical pressure. A similar protocol was followed with the mandibular premolars (n = 12), and further apical enlargement was performed with F4 and F5 manual instruments.

- The positive control group (n = 6): after extraction and access cavity preparation, instrumentation was performed intentionally beyond the apex with a SS size 80 K-file (Mani Inc) to induce microcracks.

- The negative control group (n = 6): intact teeth (no access preparation or instrumentation)

A single experienced operator, who was trained in the instrumentation protocols, performed all root canal preparations.

Instruments were used for 2 canals only and discarded. Apical patency was verified in between instruments in both groups with a SS size 10 K-file. Each canal was irrigated with 30 mL 3% sodium hypochlorite during preparation with a 30-G side-vented needle (Dentsply Maillefer). Final irrigation was performed with 5 mL 17% EDTA followed by 5 mL bidistilled water. Teeth were extracted by an experienced oral surgeon using an atraumatic technique, as previously reported. In brief, an intrasulcular incision was used to separate the mucoperiosteum from the root and bone.

Periotomes were used to sever the periodontal ligament from the root surface. Extraction was completed with luxators and forceps. The extracted teeth were stored in 0.1% thymol at 5°C for further evaluation.

Micro-CT Evaluation

All specimens were scanned using a micro- CT system (SkyScan 1176; Bruker-microCT, Kontich, Belgium) at 90 kV and 276 mA with an isotropic resolution of 17.18 mm with 180° rotation around the vertical axis, a rotation step of 0.7°, a camera exposure time of 650 milliseconds, and frame averaging of 2. X-ray was filtered with a 0.1-mm copper filter. Images were reconstructed with NRecon v.1.6.10.4 (Bruker-microCT) using 20% of beam hardening correction, ring artifact correction of 5, and smoothing of 5, resulting in the acquisition of approximately 1226 transverse cross sections per sample. A total of 43,361 cross-sectional images of roots from the cementoenamel junction to the apex were screened for the presence of dentinal microcracks using Dataviewer software version 1.5.1.2 (Bruker-microCT) by 2 previously calibrated examiners who were blinded to the experimental groups. Image analysis was repeated twice at 2-week intervals. In case of discrepancies, images were examined together, and an agreement was reached. A crack was identified as a break or disruption in the tooth structure without the separation of parts.

Statistical Analysis

The results were expressed as the percentage and number of cracked root section images for each group. The Fisher exact test was used to compare differences between the 2 experimental groups. All the analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 software (IBM Corp, Chicago, IL). The level of significance was set at P ˂ .05. The Cohen kappa was used to evaluate interexaminer variability.

Results

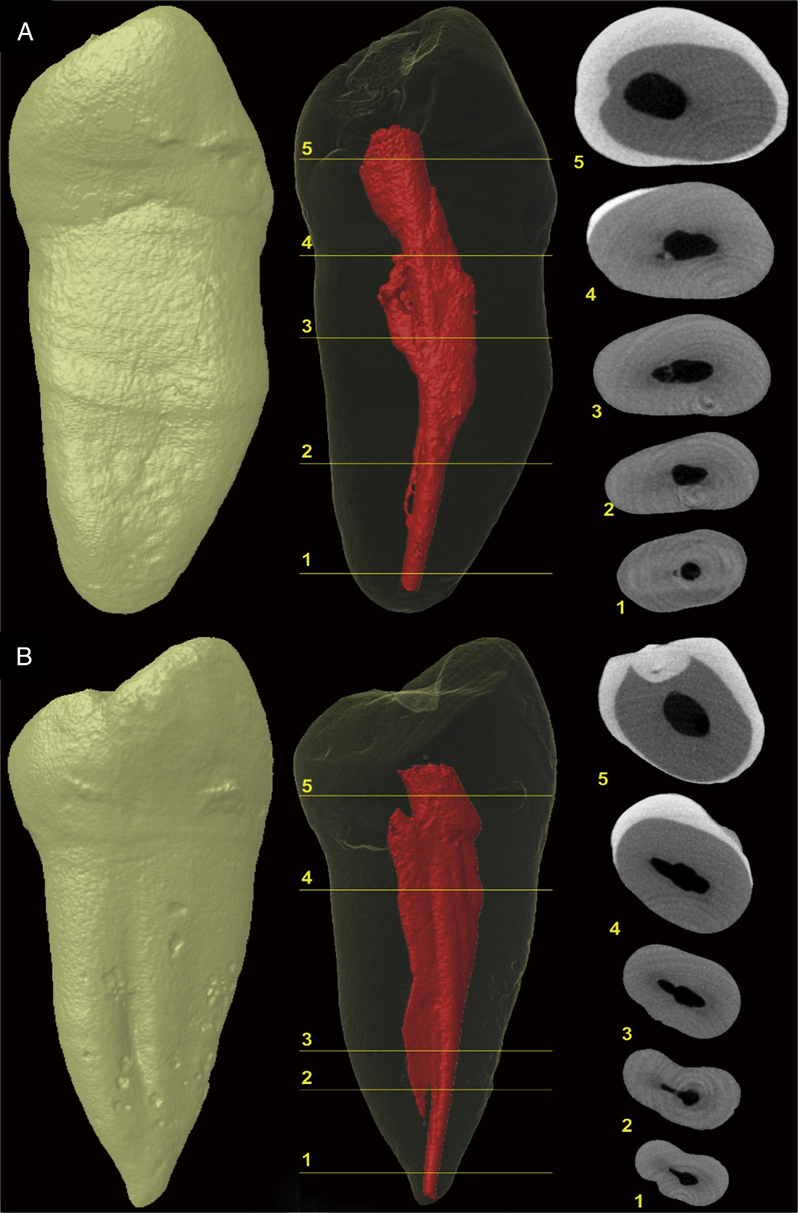

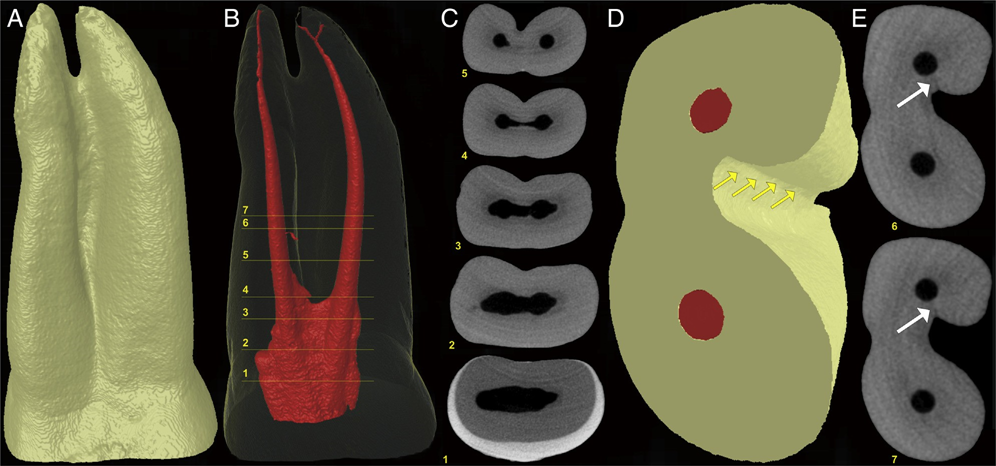

In the positive and negative control groups, 4210 and 4629 cross-sectional images of the roots were analyzed, respectively. All roots in the positive control group showed microcracks at the apical third in 792 (18.8%) sections, whereas no cracks were observed in the specimens of the negative control group (Fig. 1A and B). In the screened cross- sectional images from the PTR (n = 17,114) and PTH (n = 17,408) groups (Fig. 2A and B), microcracks were observed in 116 (0.66%) sections of the PTH group only, corresponding to 1 tooth sample. Dentin microcracks were observed in 1 tooth (1/24) in the PTH group and were not observed in the PTR group (0/24), which was not significant (P ˂ .05). These cracks extended from the external root surface into the inner root dentin at the area of reduced root dentin thickness (Fig. 3A–E). A Cohen kappa value of 0.9 was attained, indicating good interobserver reliability.

Discussion

The current study aimed to evaluate the formation of dentinal microcracks after in vivo root canal preparation of contralateral maxillary and mandibular premolars with ProTaper Universal rotary and hand instruments. Since 2014, experimental protocol has been suggested to play a major role in the results obtained while reporting postinstrumentation root microcracks. This research aimed to reduce the influence of confounding factors such as age, sex, and tooth type on sample selection by using contralateral premolars of the same patient presenting similar canal/root morphology according to a previously validated split- mouth study design. Additionally, root canal instrumentation systems used in the rotary (PTR) and hand (PTH) groups had a similar tip size and taper. The preparation protocols using the ProTaper system were chosen because of contradictory results from previous studies. Although ex vivo investigations using conventional sectioning and microscopic approaches have reported a variable incidence of microcracks (ie, 56%, 50%, and 16%) after canal instrumentation preparation with the ProTaper system, an in situ investigation using a pig jaw model reported no microcrack formation after canal instrumentation with this system.

Additionally, in vitro and in situ human cadaver–based experiments that used noninvasive micro-CT technology concluded that the mechanical instrumentation of root canals did not induce dentinal defects, whereas the microcracks observed were categorized as preexisting cracks.

The use of a human cadaver model allowed the assessment of preexisting microcracks in the experimental teeth. However, the approach does not allow the evaluation of teeth in their natural condition (i.e., supported by vital periodontium), which would most accurately reflect clinical conditions. In the current study, clinical steps for in vivo instrumentation were followed, and the teeth were subsequently evaluated using nondestructive micro-CT technology after atraumatic and careful extraction in order to avoid damage to the roots. Preoperative micro-CT scans were not performed because of the clinical nature of the study. Therefore, no information regarding the condition of the roots before canal preparation was available.

However, the current results supported the present practice because no dentinal microcrack was observed in the negative group and only one sample in the experimental groups had microcracks. This observation is in accordance with the previous micro-CT– based studies. In this study, all positive control specimens showed apical cracks in the buccolingual direction, involving the canal and the root surface, which can be attributed to the aggressive/intentional instrumentation beyond the root apex. In the experimental group, the only exception was a double-rooted maxillary first premolar of the PTH group, which showed a buccolingually oriented crack at the furcation region, similar to VRF. The crack was incomplete and originated from the root surface rather than from the root canal wall (Fig. 3E). Therefore, it could not be associated with canal preparation. Although the possibility of a preexisting crack cannot be fully excluded, in this specimen, it is likely that the presence of a deep groove in this root surface associated with the reduction of dentin thickness after instrumentation (Fig. 3D) favored microcrack formation when this root had been submitted to extraction forces.

Therefore, the null hypothesis that root canal instrumentation does not result in the formation of root dentinal microcracks in vivo was accepted. This finding is supported by a recent in situ cadaveric model study that suggests that microcracks observed in extracted teeth subjected to root canal procedures are the result of the extraction process and/or the postextraction storage conditions.

The current in vivo study was performed on patients requiring extraction of contralateral maxillary and mandibular first premolars as part of their orthodontic treatment. Maxillary premolars and mandibular premolars have been reported to be susceptible to VRF. Double-rooted maxillary premolars, single-rooted maxillary premolars, and single-rooted mandibular premolars were randomly and equally distributed in both experimental groups (Table 1). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report that assessed the potential correlation between in vivo root canal preparation and the formation of dentinal microcracks using highly accurate and noninvasive micro-CT technology. There was no significant difference between the experimental groups, suggesting that both hand and rotary instrumentation may not result in the formation of dentinal microcracks. However, 1 of the limitations of this study was that all patients were between 15 and 30 years of age. Root dentin in older individuals may exhibit a significant decrease in strength and resistance to fatigue because of changes in the microstructure and chemical composition. Also, postendodontic VRF has been reported to be more common in patients .40 years of age. Therefore, further research may be necessary to evaluate the results of root canal preparation in older patients. A micro- CT system resolution of 17.18 mm was used in this study, whereas future investigations with higher-resolution imaging may be beneficial.

Conclusion

Within the constraints of this in vivo study, it was concluded that the preparation of root canals with PTR or PTH instruments did not result in root dentinal microcracks. These findings also indicate that previous data from ex vivo experiments on root dentinal microcracks should be considered with caution.

Authors: Angambakkam Rajasekaran PradeepKumar, Hagay Shemesh, Durvasulu Archana, Marco A. Versiani, Manoel D. Sousa-Neto, Graziela B. Leoni, Yara T. C. Silva-Sousa, Anil Kishen

References:

- Tamse A. Vertical root fractures in endodontically treated teeth: diagnostic signs and clinical management. Endod Topics 2006;13:84–94.

- Versiani M, Souza E, De-Deus G. Critical appraisal of studies on dentinal radicular microcracks in endodontics: methodological issues, contemporary concepts, and future perspectives. Endod Topics 2015;33:87–156.

- Rivera EM, Walton RE. Longitudinal tooth cracks and fractures: an update and review. Endod Topics 2015;33:14–42.

- Onnink PA, Davis RD, Wayman BE. An in vitro comparison of incomplete root fractures associated with three obturation techniques. J Endod 1994;20:32–7.

- Ceyhanli KT, Erdilek N, Tatar I, Celik D. Comparison of ProTaper, RaCe and Safesider instruments in the induction of dentinal microcracks: a micro-CT study. Int Endod J 2016;49:684–9.

- Bier CA, Shemesh H, Tanomaru-Filho M, et al. The ability of different nickel-titanium rotary instruments to induce dentinal damage during canal preparation. J Endod 2009;35:236–8.

- Shemesh H, Bier CA, Wu M-K, et al. The effects of canal preparation and filling on the incidence of dentinal defects. Int Endod J 2009;42:208–13.

- Wilcox LR, Roskelley C, Sutton T. The relationship of root canal enlargement to finger-spreader induced vertical root fracture. J Endod 1997;23:533–4.

- Peters O. Current challenges and concepts in the preparation of root canal systems: a review. J Endod 2004;30:559–67.

- Adorno CG, Yoshioka T, Suda H. Crack initiation on the apical root surface caused by three different nickel-titanium rotary files at different working lengths. J Endod 2011;37:522–5.

- Adorno CG, Yoshioka T, Suda H. The effect of root preparation technique and instrumentation length on the development of apical root cracks. J Endod 2009;35:389–92.

- De-Deus G, C´esar de Azevedo Carvalhal J, Belladonna FG, et al. Dentinal microcrack development after canal preparation: a longitudinal in situ micro–computed tomography study using a cadaver model. J Endod 2017;43:1553–8.

- De-Deus G, Silva EJ, Marins J, et al. Lack of causal relationship between dentinal microcracks and root canal preparation with reciprocation systems. J Endod 2014;40:1447–50.

- De-Deus G, Belladonna FG, Souza EM, et al. Micro–computed tomographic assessment on the effect of ProTaper Next and Twisted File Adaptive systems on dentinal cracks. J Endod 2015;41:1116–9.

- De-Deus G, Cavalcante DM, Belladonna FG, et al. Root dentinal microcracks: a post-extraction experimental phenomenon? Int Endod J 2019;52:857–65.

- Bahrami P, Scott R, Galicia JC, et al. Detecting dentinal microcracks using different preparation techniques: an in situ study with cadaver mandibles. J Endod 2017;43:2070–3.

- Arias A, Lee YH, Peters CI, et al. Comparison of 2 canal preparation techniques in the induction of microcracks: a pilot study with cadaver mandibles. J Endod 2014;40:982–5.

- Rose E, Svec T. An evaluation of apical cracks in teeth undergoing orthograde root canal instrumentation. J Endod 2015;41:2021–4.

- Beertsen W, McCulloch CA, Sodek J. The periodontal ligament: a unique, multifunctional connective tissue. Periodontol 2000 1997;13:20–40.

- Graunaite I, Skucaite N, Lodiene G, et al. Effect of resin-based and bioceramic root canal sealers on postoperative pain: a split-mouth randomized controlled trial. J Endod 2018;44:689–93.

- Shen Y, Bian Z, Cheung GS, Peng B. Analysis of defects in ProTaper hand-operated instruments after clinical use. J Endod 2007;33:287–90.

- PradeepKumar AR, Shemesh H, Chang JW, et al. Preexisting dentinal microcracks in nonendodontically treated teeth: an ex vivo micro–computed tomographic analysis. J Endod 2017;43:896–900.

- Ratcliff S, Becker IM, Quinn L. Type and incidence of cracks in posterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent 2001;86:168–72.

- Johnsen GF, Sunde PT, Haugen HJ. Validation of contralateral premolars as the substrate for endodontic comparison studies. Int Endod J 2018;51:942–51.

- Capar ID, Arslan H, Akcay M, Uysal B. Effects of ProTaper Universal, ProTaper Next, and HyFlex instruments on crack formation in dentin. J Endod 2014;40:1482–4.

- Liu R, Hou BX, Wesselink PR, et al. The incidence of root microcracks caused by 3 different single-file systems versus the ProTaper system. J Endod 2013;39:1054–6.

- Fernandes PG, Novaes AB, de Queiroz AC, et al. Ridge preservation with acellular dermal matrix and anorganic bone matrix cell-binding peptide P-15 after tooth extraction in humans. J Periodontol 2011;82:72–9.

- Kishen A, Kumar GV, Chen N-N. Stress-strain response in human dentine: rethinking fracture predilection in postcore restored teeth. Dent Traumatol 2004;20:90–100.

- Chai H, Tamse A. Vertical root fracture in buccal roots of bifurcated maxillary premolars from condensation of gutta-percha. J Endod 2018;44:1159–63.

- PradeepKumar AR, Shemesh H, Jothilatha S, et al. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures in restored endodontically treated teeth: a time-dependent retrospective cohort study. J Endod 2016;42:1175–8.

- Tamse A. Iatrogenic vertical root fractures in endodontically treated teeth. Endod Dent Traumatol 1988;4:190–6.

- Yan W, Montoya C, Øilo M, et al. Reduction in fracture resistance of the root with aging. J Endod 2017;43:1494–8.

/public-service/media/default/158/GMj69_65311b2333f75.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/148/ix2WY_6531196adc6ec.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/147/bjsSM_65311952dfadf.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/460/aU9ju_671a20a2e53f3.png)