Myofunctional Therapy in Orthodontics. Functional Orofacial Disorders and Their Impact on Development

Myofunctional therapy (MFT) has gained recognition as a transformative approach in orthodontics, addressing underlying functional disorders that contribute to dentofacial anomalies. These include mixed swallowing patterns, improper tongue posture, mouth breathing, and weakened orofacial muscles. These dysfunctions, if left untreated, can adversely affect facial skeletal development, dental alignment, and even speech. The implications are particularly significant for children and adolescents, as these challenges can hinder their social adaptation and overall well-being.

What are other reasons for the development of dental alignment? Why do malocclusions emerge? Is it possible to conduct myofunctional therapy in combination with bioprogressive treatment protocols for the most effective treatment outcomes? Dive into our lessons "Etiology and Diagnosis of Malocclusions: Part 1 & Part 2" to gain a deeper understanding of the origins and principles behind malocclusions. These lessons explore the etiology from functional, traditional, and bioprogressive perspectives, alongside essential topics like Angle and Ricketts classifications, aesthetic smile analysis, and the timing of orthodontic treatment.

By integrating myofunctional therapy into orthodontic care, dental professionals can proactively address these issues. Combining therapeutic exercises with orthodontic appliances not only corrects structural concerns but also improves functional and aesthetic outcomes.

The Role of Myofunctional Therapy Across Developmental Stages

- Primary Dentition Phase

This stage focuses on setting the foundation for proper jaw growth and development. Myofunctional therapy serves as a primary intervention to eliminate harmful habits, encourage nasal breathing, and optimize oral posture. Exercises during this phase target the orbicularis oris, tongue, and jaw muscles, promoting healthy growth patterns.

- Mixed Dentition Phase

As permanent teeth begin to emerge, therapy aims to balance jaw alignment and support skeletal growth. Myofunctional therapy complements orthodontic appliances by addressing muscle imbalances and improving functional stability. Strengthening facial and oral muscles during this phase lays a stable foundation for future dental alignment.

- Permanent Dentition Phase

At this stage, MFT plays a supporting role in maintaining the results achieved through orthodontic treatment. By reinforcing orofacial musculature, therapy minimizes the risk of relapse, ensuring long-term stability of dental arches and bite alignment.

The Science Behind Myofunctional Therapy

The effectiveness of MFT lies in its ability to retrain orofacial muscles and correct harmful habits. Key elements include:

- Nasal Breathing: Encourages proper oxygenation and supports craniofacial development.

- Correct Tongue Posture: Promotes balance between dental arches.

- Facial Muscle Training: Enhances facial aesthetics and functional stability.

Benefits of Myofunctional Therapy Beyond Orthodontics

The impact of myofunctional therapy extends beyond dental health. By improving breathing, swallowing, and chewing, patients often experience better overall well-being. Early intervention can also prevent complications such as speech impediments, facial asymmetries, and reduced self-confidence, ensuring a higher quality of life.

Addressing Harmful Habits in Pediatric Patients

Harmful habits like thumb-sucking and mouth breathing are common contributors to dental and jaw anomalies. These habits can:

- Distort the shape of dental arches.

- Cause malocclusions in sagittal, transverse, and vertical planes.

- Lead to facial asymmetries and periodontal issues over time.

Thumb-Sucking: The sucking reflex is innate and peaks by six months of age, typically fading by one year. However, persistent thumb-sucking can develop into pathological oral habits that adversely affect bite formation. Long-term thumb-sucking often results in protrusion of upper front teeth, underdevelopment of the lower jaw, and an open bite.

This habit is most common among children who are bottle-fed or weaned prematurely. Stress or emotional discomfort can exacerbate thumb-sucking, which children often engage in during sleep or moments of relaxation. Persistent habits may lead to visible changes in the thumb, including thinning skin, bruising, and nail deformation.

Consequences of thumb-sucking include:

- Protrusion of upper incisors and shortening of the alveolar processes, leading to an open bite,

- Altered growth of the jaws,

- Inability to close the lips due to misaligned teeth,

- Deformation of dental arches to fit the shape of the thumb,

- Narrowing of the upper dental arch, contributing to crossbite or malocclusion.

Chronic thumb-sucking may also impact overall posture, respiratory function, and systemic health, emphasizing the need for early prevention and intervention.

Other Functional Orofacial Disorders and Their Impact on Development

Mouth Breathing: Nasal breathing is the physiological norm across all age groups. Under normal nasal breathing conditions, negative pressure is created in the oral cavity as air flows through the nasal passages and nasopharynx. During this process, the mouth remains closed, the tongue's tip rests against the oral surface of the upper incisors, and the tongue's body presses evenly against the palate. These conditions foster the development of a gently curved palate and well-formed dental arches. Mouth breathing, often caused by nasal obstructions like rhinitis or polyps, adenoids, disrupts the normal growth of facial structures, resulting in a high, narrow palate ("high-arched palate, or high-vaulted palate") and crowded teeth. This is due to positive pressure within the oral cavity, particularly on the palate, as the tongue rests at the floor of the mouth. This correlation often depends on the duration and severity of mouth breathing. Chronic mouth breathing also affects facial muscle tone, leading to further dental and skeletal anomalies.

Mouth breathing is truly a challenge that impacts health in profound ways – but with the right knowledge, you can make a difference! Join our course, "Airway and Sleep-Disordered Breathing: Integrating Myofunctional Protocols," to explore proven methods to diagnose and manage airway and sleep disorders effectively. Gain insights into the relationship between mouth breathing, TMD, and overall health, while mastering myofunctional protocols to address these issues holistically.

Speech and posture: Improper speech articulation and poor posture are frequently linked to dental abnormalities. Extended periods of poor seating posture or sleeping positions can exacerbate jaw and spine deformities, affecting a child’s overall health and development.

Mastication: Another common cause of open-mouth posture is prolonged consumption of liquid or soft foods that do not engage chewing muscles. This delays the transition from sucking to chewing. Children who struggle with chewing may avoid foods requiring jaw effort, leading to weak and undertrained masticatory muscles. Consequently, the lower jaw drops, lip closure becomes difficult, and mouth breathing sets in. Additionally, the tongue may rest in an incorrect low position, contributing to orthodontic problems like malocclusion and difficulties in sound articulation.

Tongue: When breathing through the mouth, the tongue often assumes an incorrect position, resting at the floor of the oral cavity – a condition known as glossoptosis. In a healthy swallowing pattern, the tongue's tip presses against the palate near the cervix of the upper front teeth, without protruding between the teeth. However, persistent tongue thrusting, tongue placement between the teeth, or pushing the tongue against the front teeth or cheeks in children older than 5 years may indicate a swallowing dysfunction.

Lingual Frenulum: Under normal conditions, the lingual frenulum is long and thin, extending from the middle third of the tongue to the mucous membrane of the floor of the mouth, just behind the sublingual folds. In pathological cases, the frenulum may be thick and short, attaching to the front third of the tongue and the periodontal tissue of the lower central incisors. This structural abnormality limits tongue mobility and is called a tongue-tie, or ankyloglossia. A shortened frenulum (a tongue-tie) restricts the tongue's movement, often causing it to rest between the incisors. This improper tongue position disrupts articulation and can lead to speech issues. It may also interfere with proper tooth eruption and result in an anterior open bite. However, not all tongue ties require surgical intervention and that myofunctional therapy can often improve function.

Preventive measures should focus on educating parents about the risks associated with harmful habits and ensuring timely orthodontic consultations. Proper furniture, posture during sleep, and addressing nasal or respiratory issues can significantly reduce the risk of malocclusions.

The Environmental-Genetic Nexus

Environmental influences significantly contribute to malocclusions. The equilibrium theory posits that the position of teeth within the dental arch results from the balance of forces exerted by internal (tongue, lips, cheeks) and external (habits such as thumb sucking) factors. Superimposed on these pressures are periodontal factors, including mesial drift and alveolar bone loss, and occlusal forces.

Key insights from this model include:

- Duration Over Intensity: Forces need to act for a sufficient duration (4–8 hours) to induce tooth movement. Prolonged low forces (5–10 g/cm²) are both effective and biologically conservative, while intense forces can cause root resorption and pain.

- Orthodontic Implications: Short-lived high-intensity forces, despite their magnitude, fail to move teeth, emphasizing the importance of controlled, sustained forces in treatment.

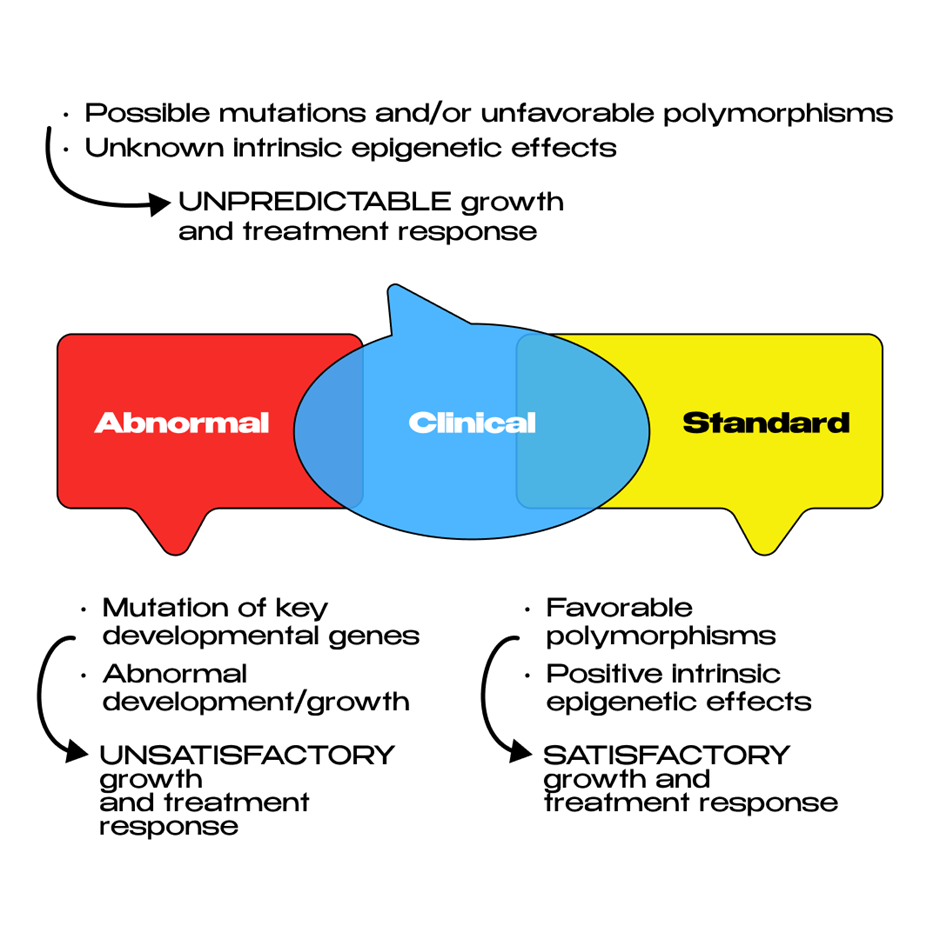

The Carlson model underscores the interplay between genetics and environmental factors in malocclusion and orthodontic outcomes. Localized disruptions such as trauma, ankylosis, or space loss exemplify environmental influences. Orthodontic treatment strategies must, therefore, address these external factors alongside genetic predispositions to achieve lasting results.

Myofunctional therapy: Exercises for Orofacial Development

The success of myofunctional therapy hinges on the severity of morphological and functional issues, the child’s dedication, and consistent supervision during exercises. Age-appropriate, engaging exercises are crucial for effectiveness, transforming treatment into an enjoyable activity. Children can practice individually or in groups at schools or daycare centers, under the supervision of parents, educators, and medical personnel.

When used as an independent treatment, myofunctional therapy is particularly effective for conditions like protrusion of the upper incisors with a neutral occlusion of posterior teeth. Exercises can be performed with or without special devices, such as labial or intraoral appliances.

Myofunctional therapy, a key component of myofunctional therapy, includes structured exercises targeting various muscle groups to restore function and symmetry. Examples include:

- Orbicularis Oris Muscle:

Training this muscle is essential, especially for children with habitual mouth breathing. After confirming nasal airway patency with a specialist, exercises can include:- Holding water in the mouth to assess nasal breathing ability.

- Blowing air onto lightweight objects like feathers.

- Compressing paper strips or cotton rolls with lips to strengthen muscles.

- Jaw and Tongue Muscles:

For addressing lower jaw alignment or improper tongue posture, recommended exercises include:- Slowly advancing the lower jaw until the front teeth overlap correctly and holding the position.

- Using resistance, such as pressing the lower jaw against fingers or wooden tools, to build strength.

- Speech-Related Exercises:

To improve tongue positioning and articulation:- Licking lips, reaching the tongue to the nose or chin.

- Clicking the tongue against the palate or practicing controlled tongue movements across teeth surfaces.

Exercises should incorporate elements of play, such as blowing onto suspended objects or using rubber rings and buttons connected by strings for resistance. Gamifying exercises makes them more appealing to children, ensuring regular practice.

Challenges and Future Directions

Myofunctional therapy is not universally applicable and has certain contraindications, including:

- Pathological hypertrophy of the facial musculature.

- Limited mobility of the temporomandibular joint.

- Class III malocclusion.

- Jaw developmental disorders caused by systemic diseases such as rickets.

While myofunctional therapy shows immense promise, challenges persist. Patient motivation and regular practice are critical to success, and the effectiveness of therapy often relies on parental involvement for younger patients. Advances such as video-guided programs offer innovative solutions, allowing patients to practice exercises at home with professional supervision.

If you’re interested to learn how myofunctional therapy truly works and want to effectively implement it in your own practice, our course is your ultimate opportunity. Join the first online congress on Myofunctional Orthodontics and Functional Jaw Orthopedics, designed to equip you with evidence-based knowledge and practical skills. Learn from top specialists across pediatric orthodontics, functional dentistry, and otorhinolaryngology as they share their extensive clinical experience and cutting-edge research!