Pulp pathosis in inlayed teeth of the ancient Mayas: a microcomputed tomography study

Abstract

Aim: To evaluate three-dimensionally, using micro-computed tomography (lCT), the anatomical relationship between the cavity prepared to hold the inlay stone and the pulp chamber in the teeth of the ancient Maya.

Methodology: Six well-preserved teeth from Maya corpses found in an archaeological site in Guatemala (approximately 1600 year old) were selected and scanned using a high-resolution lCT system (SkyScan 1174v2; SkyScan N.V., Kontich, Belgium). The sample comprised six maxillary teeth: two canines, one premolar, two central incisors and one lateral incisor. All teeth had one or two inlay stones on the buccal surface of the crown. Each specimen was scanned at an isotropic resolution of 22.5 μm, a rotational step of 0.70°, a rotational angle of 180° and a 3.1-s exposure time, using a 1-mm-thick aluminium filter. Images of each specimen were reconstructed from apex to the crown with dedicated software (NRecon v1.6.1.5) in approximately 450 slices. CTan v1.11 and CTVol v2.1 were used for three-dimensional visualization and qualitative analysis of the external and internal anatomy of the teeth.

Results: The tooth modification in all samples was classified as type E1 (one stone on the buccal surface of the crown) or E2 (two stones on the buccal surface of the crown). In the canine teeth, the cavities created to insert the inlay stone did not reach the pulp chamber. Conversely, in the maxillary incisors, the cavities clearly perforated the pulp chamber resulting in massive internal inflammatory resorption or partial calcification of the pulp cavity. In the premolar tooth, a small perforation of the pulp chamber under the buccal cusp, without morphological alteration of the intraradicular dentine, was observed.

Conclusions Microcomputed tomography analysis of teeth of the ancient Maya civilization showed that the inlay cavities cut reached the pulp chamber in the maxillary incisors and premolar teeth, with the potential to cause pulp and periapical disease.

Introduction

Evidence of body modification can be seen in almost every culture throughout history. Some of the most common forms of body modification include tattooing, body piercing, scarification, the binding of different parts of the body and the reshaping and filing of teeth (Gonzalez et al. 2010). Archaeological records of tooth modification have been found in many areas of the world, but it is most common to the ancient Mesoamerican civilizations (Van Rippen 1917, Whittlesey 1935, Rubin de la Borbolla 1940, Fastlicht 1948, Sweet 1963, Williams & White 2006, Vukovic et al. 2009). The Mayas were a Mesoamerican civilization with a highly developed culture that inhabited the Yucatan Peninsula, which comprises the Mexican states of Yucatán, Campeche and Quintana Roo; the northern part of the nation of Belize; and Guatemala’s northern. The nation’s history began about 2500 B.C., but their culture flourished from 300 A.D. to 900 A.D (Whittington & Reed 2006, Williams & White 2006). Based on archaeological findings, at least 60% of the total population was engaged in some form of tooth modification (Tiesler 1999).

In Maya’s dental practice, teeth were filed into points, ground into rectangles or cavities were prepared to permit the insertion of round pieces of stone in over a hundred different patterns. This relatively complex procedure was carried out using a hard tube that was spun between the hands or in a rope drill, with slurry of powdered quartz in water as an abrasive, to cut a cavity through the tooth enamel to allow placement of an inlay (Whittington & Reed 2006, Williams & White 2006, Vukovic et al. 2009, Gonzalez et al. 2010). These inlays were made of various minerals and were ground to fit the cavity so precisely, and the adhesive was so effective that many burials found by archaeologists today still have them firmly in place (Williams & White 2006, Gonzalez et al. 2010).

Most of the studies in this field involve the description and classification of artificially modified teeth; nonetheless, only a few examined the consequences on tooth and surrounding tissues (Gwinnett & Gorelick 1979). These studies were performed using X-ray and scanning electron microscopic analysis and have shown that, most of the time, the base of the cavity prepared to hold the inlay remained at a distance from the pulp cavity. However, perforation of the pulp chamber has also been reported, which ultimately led to periapical disease and abscess formation (Fastlicht 1948, Tiesler 2002, Whittington & Reed 2006, Gonzalez et al. 2010).

The aim of this ex vivo study was to evaluate three-dimensionally the anatomical relationship between the cavity prepared to hold the inlay stone and the pulp chamber in the teeth of the Maya, and its influence within the pulp cavity, using microcomputed tomography.

Materials and methods

Six well-preserved Maya’s teeth donated by a private collector and found in an archaeological site in Guatemala (approximately 1600 year old) were selected. All teeth had one or two inlay stones on the buccal surface of the crown.

For the experimental procedure, each specimen was vertically positioned on a metal holder in the centre of the stage and scanned in a desktop X-ray microfocus CT scanner (SkyScan 1174v2; SkyScan N.V.) at an isotropic resolution of 22.5 μm, a rotational step of 0.70°, a rotational angle of 180° and a 3.1-s exposure time, using a 1-mm-thick aluminium filter. The system consisted of a sealed air-cooled X-ray tube (20–50 kV, 40W, 800 μA) with a precision object manipulator with two translations and one rotation direction. The system also included a 14-bit CCD camera based on a 1.3-megapixel (1304 · 1024 pixels) CCD sensor.

Images of each specimen were reconstructed from apex to the crown with dedicated software (NRecon v1.6.1.5; SkyScan), which provided axial cross-sections of the inner structure of the samples in approximately 450 slices. CTan v1.11 and CTVol v2.1 (Skyscan) were used for the three-dimensional visualization and qualitative analysis of the external and internal anatomy of the teeth.

Results

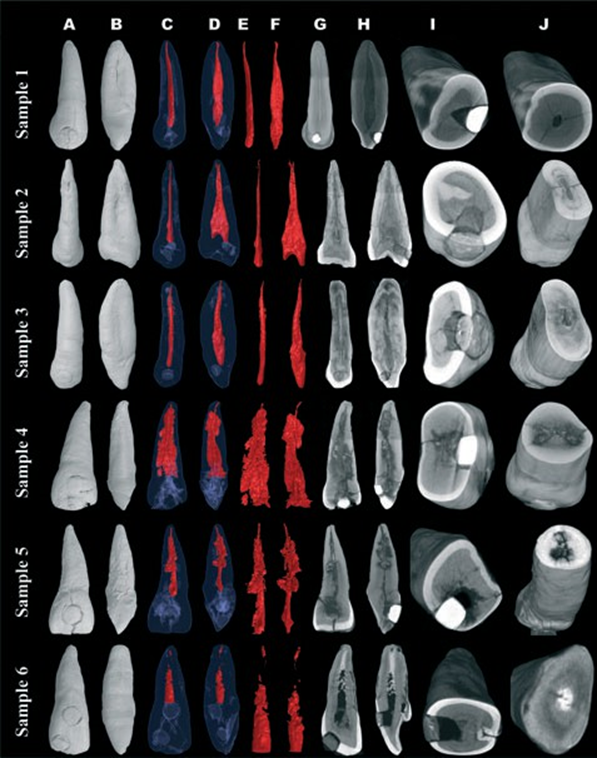

The sample comprised six maxillary teeth: two canines (samples 1 and 3), one premolar (sample 2), two central incisors (samples 4 and 5) and one lateral incisor (sample 6). Figure 1 shows the three-dimensional reconstructions of the internal and external anatomy of all specimens. The tooth modification presented in all specimens (column A) was classified as type E1 (one stone on the buccal surface of the crown), except one lateral incisor (sample 6) that was E2 (two stones on the buccal surface of the crown). In the canine teeth (samples 1 and 3), the cavities made to insert the inlay stone did not reach the pulp chamber (columns C to J). Conversely, in the maxillary incisors (samples 4–6), the cavities clearly perforated the pulp chamber (columns G to J) resulting in massive internal inflammatory resorption (samples 4 and 5, columns C to F) and partial calcification of the pulp cavity (sample 6, columns C to J). In the premolar tooth (sample 2), only a small perforation of the pulp chamber under the buccal cusp (column H), without morphological alteration of the underlying dentine (columns C to J), was observed.

stone cavity in relation to the root cavity, as well as the extension of the internal root resorption (samples 4 and 5) and the calcification of the pulp cavity (sample 6).

Discussion

Nowadays, white, properly shaped, well-aligned teeth constitute the standard for beauty and are also an indicator of health, hygiene and economic status (Gonzalez et al. 2010). Nonetheless, in ancient Mesoamerican civilizations, nontherapeutic tooth modification was a distinguishing mark of high status (Romero Molina 1970), of belonging to a tribe or clan (Alt et al. 1998) or of beauty (Van Rippen 1917, Rubin de la Borbolla 1940, Fastlicht 1948).

A complete classification of artificial modifications to human teeth has been produced by Alt et al. (1998). However, the present study used the system of Romero Molina (1970) because it constitutes the Mesoamerican standard for categorization (Williams & White 2006).

Romero defined seven basic types of tooth modifications based on the study of a collection of 1212 teeth. Each type was subdivided into at least five variants, resulting in a total of 59 different types, classified in accordance with the nature of the alteration of the crown contour, the inclusion of decorative details on the buccal surfaces or a combination of both (Gonzalez et al. 2010).

Tooth modification was found predominantly in the anterior teeth, commonly the maxillary incisors and occasionally the maxillary canines (Rubin de la Borbolla 1940, Fastlicht 1948), although cases have been documented on maxillary premolar teeth (Tiesler 1999). Regional differences have also been observed concerning the type of tooth modification. López Olivares (2006) has reported that Romero’s types E, F and G were more common in Guatemala, supporting the theory that it may represent identification with a local polity or familial lineage (Williams & White 2006). These findings are consistent with the analysed specimens.

In Maya culture, alteration of the crown contour was the most common form of tooth modification, followed by inlays or incrustations (Gonzalez et al. 2010). The types of stones used for the inlays varied geographically and temporally but include pyrite, jade, turquoise, jadeite, haematite and obsidian (Sweet 1963). In the present study, the inlays were composed of different minerals, and their radiopacity varied; no attempt was made to identify their constituents because it would damage the samples.

The most convincing evidence that tooth modification was practiced on living subjects of the Maya civilization comes from dental disease associated with excessive tooth preparation (Fastlicht 1948, Gwinnett & Gorelick 1979, Tiesler 1999, Whittington & Reed 2006, Gonzalez et al. 2010). Using radiography, dentists and anthropologists observed periapical radiolucencies related to modified teeth (Rubin de la Borbolla 1940, Fastlicht 1948, Romero Molina 1970, Whittington & Reed 2006, Gonzalez et al. 2010).

Regarding samples 1 and 3 (maxillary canine teeth), the anatomical relationship between the base of the cavity and the pulp chamber remained distant from the pulp space. As a consequence, it may be inferred that the modification procedure caused no injury to pulp tissue. On the other hand, sample 2 (premolar tooth) had an exposed pulp chamber under the buccal cusp. Inlays were secured by either pressure or cement (Rubin de la Borbolla 1940), and even though its composition was virtually identical to that of Portland cement (Sweet 1963), no hard tissue barrier was observed under the inlay. Multiple levels of responses and interactions occur in reaction to mechanical injuries of the dental pulp. Depending on the severity and duration of the insult and the host response, two distinct hard tissue changes may be induced: resorption or calcification (Torabinejad & Walton 2009), as observed in samples 4–6.

Three forms of internal root resorption have been reported, although varying terminology has been used to describe them: surface, inflammatory and replacement resorptions (Levin et al. 2009). The former occurs when just minor areas of the root canal wall have been resorbed; it might be self-limiting and might repair if the pulp is relatively healthy and if the irritating stimulus has been removed (Andreasen et al. 2007). The latter is a metaplastic type of change to the dental pulp in which the pulp first is replaced by bone, and then subsequently the dentine is replaced by bone, that appears lamella-like, with entrapped osteocyte-like cells that resemble osteons (Andreasen et al. 2007, Patel et al. 2010).

In the present study, the three-dimensional reconstruction of samples 4 and 5 suggested that both teeth developed an internal inflammatory resorption, i.e. a progressive destruction of intraradicular dentine and dentinal tubules along the canal walls (Lyroudia et al. 2002). Although chronic inflammation is commonly present in pulpal infections, other conditions prevail for the recruitment and activation of odontoclast precursors within the dental pulp (Patel et al. 2010), for example the adjacent odontoblast layer and predentine must be disrupted for the activated clastic cells to adhere to the intraradicular mineralized dentine (Wedenberg & Lindskog 1985); the pulp tissue apical to the resorptive lesion must have a viable blood supply to provide cells and their nutrients, whereas the infected necrotic coronal pulp tissue provides stimulation for those cells (Tronstad 1988).

In samples 4 and 5, it is possible that the activation of odontoclasts occurred because of the loss of predentine as a consequence of trauma or excessive heat generated during the modification procedure (Wedenberg & Lindskog 1985) and the presence of an infected necrotic coronal pulp tissue because of pulp exposure to the oral environment (Torabinejad & Walton 2009). Ultimately, as the canal was left untreated, internal resorption continued until the inflamed connective tissue filling the resorptive defect degenerated, advancing the lesion in an apical direction (Patel et al. 2010). Degenerative changes to the pulp such as pulp calcification or pulp atrophy/fibrosis are related to ageing or sublethal injury, resulting in chronic irritation to the pulp (Levin et al. 2009). This pathologic calcification is defined as an abnormal tissue deposition of calcium salts, together with smaller amounts of iron, magnesium and other mineral salts and consists in two forms. When the deposition occurs in otherwise normal tissues, it is known as metastatic calcification, and it almost always results from hypercalcaemia secondary to some disturbance in calcium metabolism. In contrast, the deposition of calcium salts locally in dying tissues is known as dystrophic calcification; it occurs despite normal serum levels of calcium and in the absence of derangements in calcium metabolism. Dystrophic calcification is encountered in areas of necrosis, whether they are of coagulative, caseous or liquefactive type, and in foci of enzymatic necrosis of fat (Robbins et al. 2010).

In the present study, extensive pathologic calcification was observed in the middle and apical thirds of the root canal of sample 6 (maxillary lateral incisor). In this case, one of the cavities made for the insertion of inlay had reached the pulp tissue. As a reaction to tissue damage in a chronically inflamed pulp, thrombi in blood vessels and collagen sheaths around vessel walls have been considered as possible sites for the beginning of dystrophic calcifications. As irritation increased, the amount of calcification also increased, leading to partial obliteration of the root canal (Torabinejad & Walton 2009).

Conclusions

Intentional modifications of human teeth hold anthropological and social significance. Their study helps to understand past and present human behaviour from a geographic, cultural, religious and aesthetic perspective. Tomography analysis of teeth of the ancient Maya civilization showed that the inlay cavities cut reached the pulp chamber in the maxillary incisors and premolar teeth, with the potential to cause pulp and periapical disease.

Authors: M. A. Versiani, M. D. Sousa-Neto & J. D. Pécora

References:

- Alt KW, Rösing FW, Teschler-Nicola M (1998) Artificial modifications of human teeth. Dental Anthropology: Fundamentals, Limits, and Prospects, 1st edn. New York, NY, USA: Springer-Verlag Wien, pp. 386–415.

- Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L (2007) Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth, 4th edn. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Munksgaard.

- Fastlicht S (1948) Tooth mutilations in Pre-Columbian Mexico. Journal of the American Dental Association 36, 315–23.

- Gonzalez EL, Perez BP, Sanchez JA, Acinas MM (2010) Dental aesthetics as an expression of culture and ritual. British Dental Journal 208, 77–80.

- Gwinnett AJ, Gorelick L (1979) Inlayed teeth of ancient Mayans: a tribological study using the SEM. Scanning Electron Microscopy 12, 575–80.

- Levin LG, Law AS, Holland GR, Abbott PV, Roda RS (2009) Identify and define all diagnostic terms for pulpal health and disease states. Journal of Endodontics 35, 1645–57.

- López Olivares NM (2006) Cultural odontology: dental alterations from Petén, Guatemala. In: Whittington SL, Reed DM, eds. Bones of the Maya: Studies of Ancient Skeletons, 2nd edn. Washington, DC, USA: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 105–16.

- Lyroudia KM, Dourou VI, Pantelidou OC, Labrianidis T, Pitas IK (2002) Internal root resorption studied by radiography, stereomicroscope, scanning electron microscope and computerized 3D reconstructive method. Dental Traumatology 18, 148–52.

- Patel S, Ricucci D, Durak C, Tay F (2010) Internal root resorption: a review. Journal of Endodontics 36, 1107–21. Robbins SL, Kumar V, Cotran RS (2010) Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 8th edn. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Saunders/Elsevier.

- Romero Molina J (1970) Dental mutilation, trephination, and cranial deformation. In: Stewart TD, ed. Physical Anthropology, 1st edn. Austin, TX, USA: University of Texas Press, pp. 50–67. Rubin de la Borbolla DF (1940) Types of tooth mutilation found in Mexico. The American Journal of Physical Anthropology 26, 349–65.

- Sweet APS (1963) Pre-hispanic indian dentistry. Dental Radiography and Photography 36, 19–22.

- Tiesler V (1999). Head shaping and dental decoration among the ancient Maya: archaeological and cultural aspects. In: Proceedings of the 64th Meeting of the Society of American Archaeology. Chicago, IL, USA: Society of American Archaeology, pp. 1–11. Tiesler V (2002) Endodontics: decoration techniques in ancient Mexico – a study of dental surfaces using radiography and S.E.M. Oral Health 92, 33–41.

- Torabinejad M, Walton RE (2009) Endodontics: Principles and Practice, 4th edn. St. Louis, MO, USA: Saunders/Elsevier.

- Tronstad L (1988) Root resorption – etiology, terminology and clinical manifestations. Endodontics and Dental Traumatology 4, 241–52.

- Van Rippen B (1917) Pre-Columbian operative dentistry of the Indians of Middle and South America. Dental Cosmos LIX, 861–73.

- Vukovic A, Bajsman A, Zukic S, Secic S (2009) Cosmetic dentistry in ancient times – a short review. Bulletin of the International Association for Paleontology 3, 9–13.

- Wedenberg C, Lindskog S (1985) Experimental internal resorption in monkey teeth. Endodontics G Dental Traumatology 1, 221–7.

- Whittington SL, Reed DM (2006) Bones of the Maya: Studies of Ancient Skeletons, 1st edn. Tuscaloosa, AL, USA: The University of Alabama Press.

- Whittlesey HG (1935) History and development of dentistry in Mexico. Journal of the American Dental Association 6, 989–95. Williams JS, White CD (2006) Dental modification in the postclassic population from Lamanai, Belize. Ancient Mesoamerica 17, 139–51.