Micro-CT assessment of dentinal micro-cracks after root canal filling procedures

Aim: To evaluate the frequency of dentinal micro-cracks after root canal filling procedures with GuttaCore (GC), cold lateral compaction (CLC) and warm vertical compaction (WVC) techniques in mandibular molars using micro-computed tomographic analysis.

Methodology: Thirty mesial roots of mandibular molars, with a type II Vertucci’s canal configuration, were prepared to working length with a Reciproc R40 instrument and randomly assigned to one of 3 experimental groups (n = 10), according to the technique used for root filling: GC, CLC or WVC. The GC group was filled with a size 40 GC obturator, while CLC and WVC groups used conventional gutta-percha cones. AH Plus sealer was used in all groups. The specimens were scanned at an isotropic resolution of 14.25 μm before and after root canal preparation and after root filling. Then, all pre- and postoperative cross-sectional images of the roots (n = 41,660) were screened to identify the presence of dentinal defects.

Results: Overall, 30.75% (n = 12,810) of the pre + post-filling images displayed dentinal defects. In the GC, CLC and WVC groups, dentinal micro-cracks were observed in 18.68% (n = 2,510), 15.99% (n = 2,389), and 11.34% (n = 1,506) of the cross-sectional images, respectively. All micro-cracks identified in the post-filling scans were also observed in the corresponding post-preparation images.

Conclusion: Root fillings in all techniques did not induce the development of new dentinal micro-cracks.

Introduction

The main purpose of root filling is to create a fluid-tight seal within the root canal space to prevent the passage of fluids/toxins, which could compromise the treatment outcome (Schilder 1967). Cold lateral compaction (CLC) and warm vertical compaction (WVC) are techniques largely recommended to improve the overall quality of the root filling (Harvey et al. 1981). Although CLC has been used for many decades and was proven clinically effective (Aqrabawi 2006, Marquis et al. 2006), it appears to generate forces that trigger the development of dentinal defects (Shemesh et al. 2009). Similarly, despite the improved adaptation of the filling materials to the root canal walls using WVC techniques (Keleş et al. 2014), the forces produced during vertical compaction of the thermoplasticed materials with pluggers may also initiate tensile stresses that might cause or aggravate dentinal cracks (Shemesh et al. 2010). The challenge is to pursue a filling technique that improves the spreadability of the filling materials within the root canal system and, at the same time, maintaining the tensile stress over the root canal walls to a minimum. These goals can be achieved using carrier-based thermoplastic techniques in which gutta-percha is softened in an oven before being carried into the root canal (Gutmann 2011). To date, however, no study has assessed the incidence of dentinal defects after root filling with this technique.

The body of evidence on dentinal cracks induced by root filling procedures is based on two- dimensional, destructive conventional models. Therefore, there is a lack of non-destructive longitudinal experimental report on the possible cause-effect relationship between root filling and dentinal micro-cracks. Micro-computed tomography technology (micro-CT) has allowed new perspectives for endodontic research by enabling quantitative and qualitative non-destructive assessment of the root canal system before and after endodontic procedures (Versiani et al. 2013, Keleş et al. 2014, De-Deus et al. 2015a). Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the frequency of dentinal micro-cracks observed after root filling with GuttaCore (GC; Dentsply Tulsa Dental Specialties, Tulsa, OK, USA), CLC and WVC techniques through micro-CT analysis. The null hypothesis was that these root filling techniques are unable to generate dentinal micro-cracks.

Materials and methods

Sample selection

Approval for the project was obtained from the local Ethics Committee. One hundred and ninety-three human mandibular first and second molars with completely separated roots, extracted for reasons not related to this study, were obtained from a pool of teeth. All roots were initially inspected with the aid of a stereomicroscope under 12X magnification to detect and exclude teeth with pre- existing cracks. Then, digital radiographs were taken in the buccolingual direction to determine the curvature angle of the mesial root (Schneider 1971). Only teeth with moderate curvature of the mesial root (ranging from 10° to 20°) and root canals patent to their length with a size 10 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) were selected. The specimens were decoronated, and the distal roots were removed by using a low-speed saw, water cooling (Isomet; Buhler Ltd, Lake Bluff, NY, USA) leaving mesial roots with approximately 12 ± 1 mm in length to prevent the introduction of confounding variables. As a result, ninety-three mesial roots of mandibular molars were selected and stored in 0.1% thymol solution at 5°C.

To obtain an overall outline of the root canal anatomy, the mesial roots were prescanned in a relatively low isotropic resolution (70 μm) using a micro-CT scanner (SkyScan 1173; Bruker microCT, Kontich, Belgium) at 70 kV and 114 mA. Based on the 3D models achieved from the pre-scan set of images, thirty specimens with Vertucci’s type II canal configuration (Vertucci 1984) were scanned at an increased isotropic resolution of 14.25 μm using 360° rotation around the vertical axis, a rotation step of 0.5º, camera exposure time of 7000 milliseconds, and frame averaging of 5. X-rays were filtered with a 1 mm-thick aluminum filter. The images were reconstructed with NRecon v.1.6.9 software (Bruker microCT), using 40% beam hardening correction and ring artifact correction of 10 and resulting in the acquisition of 700-800 transverse cross-sections per tooth.

Cleaning and shaping

A thin film of polyether impression material was used to coat the root surface to simulate the periodontal ligament (Liu et al. 2013), and each specimen was placed corono-apically inside a custom-made epoxy resin holder (Ø 18 mm) to streamline further co-registration processes. Apical patency was determined by inserting a size 10 K-file into the root canal until its tip was visible at the apical foramen, and the working length (WL) was set 1.0 mm shorter than this measurement. Then, a glide path was established with a size 15 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer) up to the WL.

Mesial root canals were prepared with a Reciproc R40 instrument (VDW, Munich, Germany) driven with the VDW Silver motor (VDW) in “RECIPROC ALL” mode. The instrument was used with a slow in-and-out pecking motion of about 3 mm in amplitude with a light apical pressure in a reciprocating motion until the WL was reached. After 3 pecking motions, the instrument was removed from the canal and cleaned. Following each file use or insertion, patency was confirmed using a size 10 K-file. Irrigation was performed using a total of 30 mL 5.25% NaOCl, followed by a final rinse with 5 mL 17% EDTA (pH = 7.7) and 5 mL bidistilled water. Hence, a total volume of 40 mL irrigant was used per canal. Then, canals were dried with absorbent Reciproc R40 paper points (VDW). After cleaning and shaping procedures, the mesial roots were scanned and reconstructed using the previously mentioned parameters.

Root canal filling

After root canal preparation, the specimens were randomly assigned to one of the 3 experimental groups (n = 10), according to the technique used for root filling: GC, CLC, and WVC.

In the GC group, each canal was filled with a size 40, 0.06 taper GC obturator (Dentsply Tulsa Dental Specialties) and AH Plus sealer (Dentsply De Trey, Konstanz, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s directions. Briefly, the shape of the canal space at the WL and passive fit of the obturator were assessed using a verifier instrument (Dentsply Tulsa Dental Specialties). Then, a GC obturator was heated (GuttaCore Heater Obturator Oven; Dentsply Tulsa Dental Specialties) for 30 seconds and slowly inserted up to the WL with the canal previously coated with AH Plus sealer. Thereafter, the shaft and handle of the obturator were removed using a round bur in a high-speed handpiece under copious water spray at the cementoenamel junction level.

In the CLC group, a size 40, 0.02 taper gutta-percha master cone (Dentsply Tulsa Dental Specialties) coated with AH Plus sealer was inserted up to the WL. Lateral condensation was achieved in each canal using fine-medium accessory cones (DiaDent, Burnaby, BC, Canada) with the aid of a size B finger spreader (Dentsply Maillefer). The spreader was firstly introduced 3 mm short of the WL and compaction was carried out until 6 mm coronal from this point. The coronal excess of gutta-percha was removed with a heated instrument.

In the WVC group, each canal was fitted with a Reciproc R40 gutta-percha cone (VDW; size 40, 0.06 taper) that was used to apply the AH Plus sealer on the canal walls. A plugger (M Plugger; EIE/Analytic, Redmond, WA, USA) that penetrated to within 5 mm of the WL was selected. A System B unit (SybronEndo, Orange, California, USA) was preset to 200°C during the condensation of the primary gutta-percha cone (down-pack) and to 100°C when adapting and condensing the apical portion of the backfill by compacting 2-mm increments of heated gutta-percha; finally, at 250°C, the remainder of the secondary cone was softened prior to vertical condensation. In CLC and WVC groups, the force applied to the spreader or plugger was controlled using a household digital scale and kept at a maximum of 2 kg (Blum et al. 1997).

After root filling procedures, the coronal 1-mm of the filling materials was removed, the cavity filled with a temporary filling material (Cavit; 3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany), and the teeth stored in sterile, distilled water (37° C and 100% relative humidity) to ensure complete setting of the sealer. Then, a post root filling micro-CT scans of each specimen was performed using the same parameters. A single-experienced operator performed all experimental procedures to avoid interoperator variability.

Dentinal micro-crack evaluation

An automatic superimposition process based on the outer root contour using 1000 interactions with Seg3D v.2.1.5 software (SCI Institute’s National Institutes of Health-National Institute of General Medical Sciences CIBC Center, Bethesda, MD, USA) co-registered the image stacks of the specimens after canal preparation and after root filling procedures. Then, the cross-sectional images of the mesial roots were screened by 3 previously calibrated examiners from the furcation level to the apex (n = 41,660) to identify the presence of dentinal micro-cracks. Firstly, post-filling images were analyzed and the number of the cross-sections with dentinal defect was recorded. Afterward, the post- preparation corresponding cross-sectional images were examined to verify the pre-existence of such dentinal defect. To validate the screening process, image analyses were repeated twice at 2-week intervals; in case of divergence, the images were examined at the same time by the three evaluators until reaching an agreement.

Results

Overall, 30.75% (n = 12,810) of the pre + post-filling images displayed dentinal defects. Dentinal micro-cracks after cleaning and shaping procedures were observed in 18.68% (n = 2,510), 15.99% (n = 2,389), and 11.34% (n = 1,506) of the cross-sectional images of GC, CLC, and WVC groups, respectively. This was the same amount of defects observed in the corresponding post-filling images, which means that root canal filling procedures with all tested techniques did not generate new micro-cracks.

Discussion

This is the first study evaluating the incidence of dentinal defects after root canal filling using a non-destructive imaging methodology. Micro-CT technology provides the possibility to examine root before any root canal procedure. Considering that the overall storage conditions before, during and after the endodontic procedures might affect the incidence of dentinal defects, in the current study, extracted teeth stored in a liquid medium were used (Bürklein et al. 2013, Liu et al. 2013). Despite recently unpublished reports that have pointed out the occurrence of spontaneous cracking in thin cross-section slices of dentine after a short period of drying, no new micro-cracks were observed during the scanning procedures in the non-humid conditions. This may be explained because the structure of the root was kept intact as no sectioning procedure was performed. In this way, it may be hypothesized that the microstructure of the dentine is less affected by the non-humid conditions of 25- minutes scanning procedure than when the root is sectioned in thin slices.

The present results indicated that GC, CLC, and WVC techniques were not associated with the development of new dentinal defects, considering that each micro-crack observed in the cross- section slices after the root filling procedures was also present in the corresponding post-preparation images. This outcome contrasts with those of previous studies in which a direct relationship between canal filling and the development of dentinal micro-cracks was demonstrated (Shemesh et al. 2009, Barreto et al. 2012, Kumaran et al. 2013, Topçuoğlu et al. 2014, Çapar et al. 2015). Shemesh et al. (2009) observed that both lateral compaction and passive root filling techniques created dentinal defects, with the former showing significantly more defects. In another study, it was also reported that the lateral compaction group had significantly more dentinal defects than the prepared but non-filled control group (Shemesh et al. 2010). Similarly, Kumaram et al. (2013) found that lateral compaction significantly produced more defects than passive root filling. Topçuoğlu et al. (2014) observed dentinal defects in teeth filled using the passive technique while Çapar et al. (2015) showed that only 1 new crack was observed after single-cone filling procedures. Conversely, Barreto et al. (2012) did not find any differences regarding the incidence of dentinal defects when comparing prepared canals filled with different techniques. The discrepancy of the present results with those previously reported may be explained by differences in the methodological design, including dissimilarities regarding the filling protocols, observational methods, sample selection, and also the nomenclature used to classify the defects (Versiani et al. 2015).

The association of root canal filling techniques with the development of dentinal defects has been largely based on root-sectioning methods with direct visualization of the specimens by optical microscopy (Shemesh et al. 2009, Barreto et al. 2012, Kumaran et al. 2013, Topçuoğlu et al. 2014, Çapar et al. 2015). This procedure has the disadvantage of its destructive nature, which was probably the main cause of the reported outcomes. In the majority of these studies, control groups used unprepared teeth in which no dentinal defect was observed (Shemesh et al. 2009, Kumaran et al. 2013, Topçuoğlu et al. 2014, Çapar et al. 2015); however, in these groups, the authors did not take into account the potential damage to the root dentine produced by the combined action of the mechanical canal preparation and filling, the chemical attack of the NaOCl-based irrigant, and the sectioning procedures. This methodological flaw has been recently highlighted in two micro-CT studies in which root canal preparation with different nickel-titanium systems did not induce the formation of new dentinal micro-cracks (De-Deus et al. 2014, 2015b). Interestingly, in the three studies using the same conventional root-sectioning methods, dentinal defects were also observed in the untreated control group (Barreto et al. 2012, Bürklein et al. 2013, Arias et al. 2014). Authors linked its presence to excessive mastication or extraction forces applied to the roots (Barreto et al. 2012, Arias et al. 2014).

One may still argue that, compared to microscopic evaluation, the micro-CT output image may be of low resolution resulting in reduced threshold to evaluate the formation of new dentinal defects. In comparison to conventional tomography, micro-CT technology uses high-energy X-rays with smaller focal spots, finer and more densely packed detectors and longer exposure times, which are more effective at penetrating dense materials, allowing a spatial resolution that is far superior compared to various cross-sectional image outputs acquired with microscopes. In most of these studies, microscopic magnification ranges from 8X to 25X (Bier et al. 2009, Shemesh et al. 2009, Bürklein et al. 2013, Hin et al. 2013, Liu et al. 2013, Abou El Nasr & Abd El Kader 2014, Arias et al. 2014, Arslan et al. 2014, Kansal et al. 2014, Priya et al. 2014, Adl et al. 2015, Aydin et al. 2015, Karataş et al. 2015, Ustun et al. 2015). In a preliminary investigation by the present authors (data not yet published), a micro-CT investigation of several ranges and extensions of defective-positive dentinal slices was performed to address whether the full extension of dentinal micro-cracks visualized under conventional stereomicroscopy were also observed through micro-CT cross-sectional images. The results confirmed though the reliability of this contemporary technology for detecting dentinal defects as no single defect observed in the stereomicroscopy has undetected by the micro-CT.

Micro-CT non-destructive technology also has several advantages over the well-established root sectioning approach. While the later allows the analysis of only a few slices per tooth, which may result in loss of information, the highly accurate micro-CT method (De-Deus et al. 2014, 2015a, 2015b) enables the evaluation of hundreds of slices per sample. This explains the lower frequency of dentinal micro-cracks observed in control groups of root-sectioning models compared to micro-CT studies (De-Deus et al. 2014, 2015b). Besides, this new technology allows not only the visualization of pre-existing dentinal defects but also their precise location throughout the root, before and after canal filling, improving the internal validity of the experiment since each specimen acts as its own control. In addition, micro-CT technology allows overlapping further experiments on the same specimens, tracking the development of dentinal defects after root canal retreatment, post-space preparation, and post-removal procedures.

Figure legend

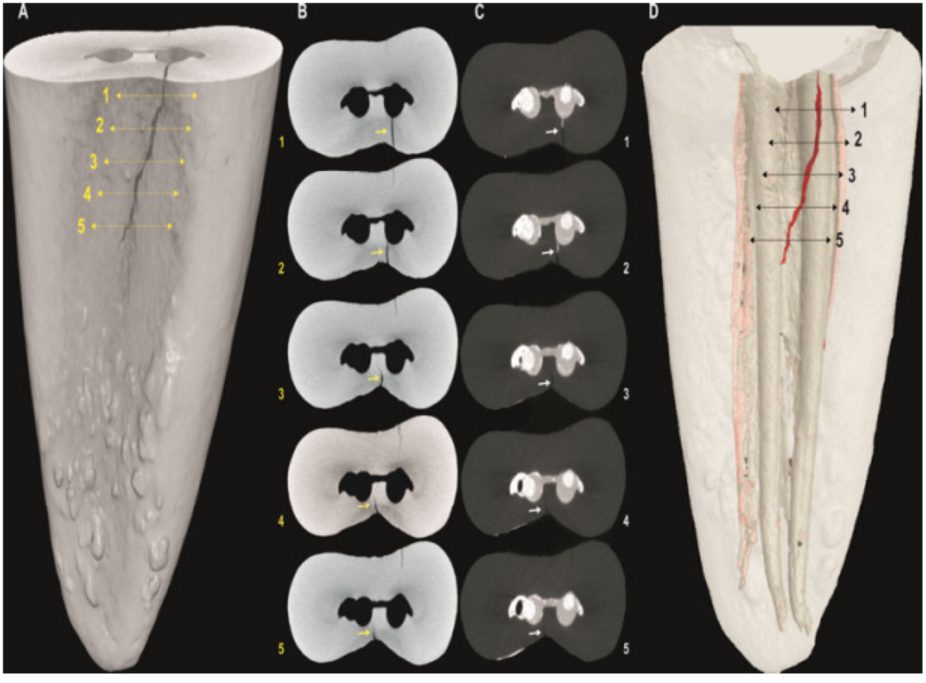

Figure 1 (a) 3D model of a mesial root of a mandibular first molar presenting a micro-crack in its distal aspect. (b-c) representative cross-sections of the coronal third of the same root after root canal preparation and filling, respectively showing that the fracture line changes its position according to the level of the section. While in the first 3 sections the fracture would be classified as a 'complete fracture', in the other sections, the extension of the same fracture would lead to classified then as 'incomplete fractures' or fractures not related to the root canals. (d) Image showing the 3D view of the micro-crack in the filled mesial root.

Conclusion

Under the conditions of this study, it can be concluded that root filling procedures with GC, CLC, and WVC techniques did not induce the development of new dentinal micro-cracks.

Authors: G. De-Deus, F. G. Belladonna, E. J. N. L. Silva, E. M. Souza, J. C. A. Carvalhal, R. Perez, R. T. Lopes, M. A. Versiani

References:

- Abou El Nasr HM, Abd El Kader KG (2014) Dentinal damage and fracture resistance of oval roots prepared with single-file systems using different kinematics. Journal of Endodontics 40, 849-51.

- Adl A, Sedigh-Shams M, Majd M (2015) The effect of using RC Prep during root canal preparation on the incidence of dentinal defects. Journal of Endodontics 41, 376-79.

- Aqrabawi JA (2006) Outcome of endodontic treatment of teeth filled using lateral condensation versus vertical compaction (Schilder’s technique). The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice 15, 17-24.

- Arias A, Lee YH, Peters CI, Gluskin AH, Peters OA (2014) Comparison of 2 canal preparation techniques in the induction of microcracks: a pilot study with cadaver mandibles. Journal of Endodontics 40, 982-85.

- Arslan H, Karataş E, Capar ID, Ozsu D, Doğanay E (2014) Effect of ProTaper Universal, Endoflare, Revo-S, HyFlex coronal flaring instruments, and Gates Glidden drills on crack formation. Journal of Endodontics 40, 1681-83.

- Aydin U, Aksoy F, Karataslioglu E, Yildirim C (2015) Effect of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid gel on the incidence of dentinal cracks caused by three novel nickel-titanium systems. Australian Endodontic Journal 41, 104-10.

- Barreto MS, Moraes Rdo A, Rosa RA, Moreira CH, Só MV, Bier CA (2012) Vertical root fractures and dentin defects: effects of root canal preparation, filling, and mechanical cycling. Journal of Endodontics 38, 1135-9.

- Bier CAS, Shemesh H, Tanomaru-Filho M, Wesselink PR, Wu M-K (2009) The ability of different nickel-titanium rotary instruments to induce dentinal damage during canal preparation. Journal of Endodontics 35, 236-38.

- Blum JY, Parahy E, Micallef JP (1997) Analysis of the forces developed during obturation: warm vertical compaction. Journal of Endodontics 23, 91-5.

- Bürklein S, Tsotsis P, Schäfer E (2013) Incidence of dentinal defects after root canal preparation: reciprocating versus rotary instrumentation. Journal of Endodontics 39, 501-4.

- Çapar İD, Uysal B, Ok E, Arslan H (2015) Effect of the size of the apical enlargement with rotary instruments, single-cone filling, post space preparation with drills, fiber post removal, and root canal filling removal on apical crack initiation and propagation. Journal of Endodontics 41, 253-6.

- De-Deus G, Silva EJ, Marins J et al (2014) Lack of causal relationship between dentinal microcracks and root canal preparations with reciprocation systems. Journal of Endodontics 40, 1447-50.

- De-Deus G, Marins J, Silva EJ et al (2015a) Accumulated hard tissue debris produced during reciprocating and rotary nickel-titanium canal preparation. Journal of Endodontics 41, 676-81.

- De-Deus G, Belladonna FG, Souza EM et al (2015b) Micro-computed tomographic assessment on the effect of ProTaper Next and Twisted File Adaptive systems on dentinal cracks. Journal of Endodontics 41, 1116-9.

- Gutmann JL (2011) The future of root canal obturation. Dentistry Today 30, 130-1.

- Harvey TE, White JT, Leeb IJ (1981) Lateral condensation stress in root canals. Journal of Endodontics 7, 151-5.

- Hin ES, Wu M-K, Wesselink PR, Shemesh H (2013) Effects of Self-Adjusting File, Mtwo, and ProTaper on the root canal wall. Journal of Endodontics 39, 262-4.

- Kansal R, Rajput A, Talwar S, Roongta R, Verma M (2014) Assessment of dentinal damage during canal preparation using reciprocating and rotary files. Journal of Endodontics 40, 1443-6.

- Karataş E, Gunduz HA, Kırıcı DO, Arslan H, Topcu MC, Yeter KY (2015) Dentinal crack formation during root canal preparations by the Twisted File Adaptive, ProTaper Next, ProTaper Universal, and WaveOne instruments. Journal of Endodontics 41, 261-4.

- Keleş A, Alcin H, Kamalak A, Versiani MA (2014) Oval-shaped canal retreatment with self-adjusting file: a micro-computed tomography study. Clinical Oral Investigations 18, 1147-53.

- Kumaran P, Sivapriya E, Indhramohan J, Gopikrishna V, Savadamoorthi KS, Pradeepkumar AR (2013) Dentinal defects before and after rotary root canal instrumentation with three different obturation techniques and two obturating materials. Journal of Conservative Dentistry 16, 522-6.

- Liu R, Hou BX, Wesselink PR, Wu MK, Shemesh H (2013) The incidence of root microcracks caused by 3 different single-file systems versus the ProTaper system. Journal of Endodontics 39, 1054-6.

- Marquis VL, Dao T, Farzaneh M, Abitbol S, Friedman S (2006) Treatment outcome in endodontics: the Toronto Study. Phase III: initial treatment. Journal of Endodontics 32, 299-306.

- Priya NT, Chandrasekhar V, Anita S, Tummala M, Raj TBP, Badami V, Kumar P, Soujanya E (2014) “Dentinal microcracks after root canal preparation” a comparative evaluation with hand, rotary and reciprocating instrumentation. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 8, 70-2.

- Schilder H (1967) Filling root canals in three dimensions. Dental Clinics of North America, 723-44.

- Schneider SW (1971) A comparison of canal preparations in straight and curved root canals. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology 32, 271-5.

- Shemesh H, Bier CA, Wu MK, Tanomaru-Filho M, Wesselink PR (2009) The effects of canal preparation and filling on the incidence of dentinal defects. International Endodontic Journal 42, 208- 13.

- Shemesh H, Wesselink PR, Wu MK (2010) Incidence of dentinal defects after root canal filling procedures. International Endodontic Journal 43, 995-1000.

- Topçuoğlu HS, Demirbuga S, Tuncay Ö, Pala K, Arslan H, Karataş E (2014) The effects of Mtwo, R- Endo, and D-RaCe retreatment instruments on the incidence of dentinal defects during the removal of root canal filling material. Journal of Endodontics 40, 266-70.

- Ustun Y, Sagsen B, Aslan T, Kesim B (2015) The effects of different nickel-titanium instruments on dentinal microcrack formations during root canal preparation. European Journal of Dentistry 9, 41-6.

- Versiani MA, Leoni GB, Steier L et al (2013) Micro-computed tomography study of oval-shaped canals prepared with the Self-Adjusting File, Reciproc, WaveOne, and ProTaper Universal systems. Journal of Endodontics 39, 1060-6.

- Versiani MA, Souza E, De-Deus G (2015) Critical appraisal of studies on dentinal radicular microcracks in endodontics: methodological issues, contemporary concepts, and future perspectives. Endodontics Topics 33, 87-156.

- Vertucci FJ (1984) Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology 58, 589-99.