Lack of Causal Relationship between Dentinal Microcracks and Root Canal Preparation with Reciprocation Systems

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to evaluate the frequency of dentinal microcracks observed after root canal preparation with 2 reciprocating and a conventional full- sequence rotary system using micro–computed tomographic analysis.

Methods: Thirty mesial roots of mandibular molars presenting a type II Vertucci canal configuration were scanned at an isotropic resolution of 14.16 mm. The sample was randomly assigned to 3 experimental groups (n = 10) according to the system used for the root canal preparation: group A—Reciproc (VDW, Munich, Germany), group B—WaveOne (Dentsply Maillefer, Baillagues, Switzerland), and group C—BioRaCe (FKG Dentaire, La-Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland). Second and third scans were taken after the root canals were prepared with instruments sizes 25 and 40, respectively. Then, pre- and postoperative cross-section images of the roots (N = 65,340) were screened to identify the presence of dentinal defects.

Results: Dentinal microcracks were observed in 8.72% (n = 5697), 11.01% (n = 7197), and 7.91% (n = 5169) of the cross-sections from groups A (Reciproc), B (WaveOne), and C (BioRaCe), respectively. All dentinal defects identified in the postoperative cross-sections were also observed in the corresponding preoperative images.

Conclusions: No causal relationship between dentinal microcrack formation and canal preparation procedures with Reciproc, WaveOne, and BioRaCe systems was observed. (J Endod 2014;40:1447–1450)

Recently, a new technique using reciprocating motion was proposed for root canal preparation. This approach relieves the stress on the instrument by special counterclockwise (cutting action) and clockwise (release of the instrument) movements and, therefore, increases its resistance to cyclic fatigue in comparison with traditional continuous rotation motion. Reciproc (VDW, Munich, Germany) and WaveOne (Dentsply Maillefer, Baillagues, Switzerland) are the main examples of commercially available single-file reciprocating systems for root canal preparation that alternate different values of counterclockwise and clockwise rotation movements, allowing 360◦ preparation after running a series of reciprocating movements.

Albeit the existence of a body of evidence on safety and shaping effectiveness of the reciprocating motion, concerns have been raised about some potential injurious side effect of this new kinematic applied to nickel-titanium instruments. According to some recent studies, reciprocating instruments would be more prone to promote the development or propagation of dentin microcracks and dentinal damage than conventional full-sequence rotary systems. This rationale claims that the root canal preparation using only a single large-tapered reciprocating instrument, which cuts substantial amounts of dentin in a short time, tends to create or aggravate more dentinal defects than conventional preparation, which comprises a more progressive and slower mechanical enlargement. From a clinical standpoint, these dentinal defects, such as craze lines and microcracks, are important because they may further develop into vertical root fractures, which might lead to tooth loss.

In the last years, micro–computed tomographic technology (micro-CT) has opened up new possibilities for endodontic research by allowing nondestructive volumetric quantitative and qualitative assessments before and after different endodontic procedures. Thus, the present study was designed to evaluate the frequency of dentinal microcracks observed after root canal preparation with 2 reciprocating systems (Reciproc and WaveOne) using micro-CT analysis. Conventional full-sequence rotary system (BioRaCe; FKG Dentaire, La-Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland) was used as a reference technique for comparison.

Materials and Methods

Sample Size Calculation

Sample size was calculated after the effect size estimation of dentinal defects promoted by reciprocating and rotary systems as reported by Bürklein et al. In that study, the percentage sum of the specimens with complete and incomplete dentinal cracks ranged from 18.3%–51.6%. Using the chi-square test family and variance statistical test (G*Power 3.1 for Macintosh; Heinrich Heine, Universitat Dusseldorf, Dusseldorf, Germany) with a = 0.05 and b = 0.95, a calculated effect size of 7.6 was input. Eight samples were indicated as the minimum ideal size required for observing the same effect of instruments over dentin.

Sample Selection

This study was revised and approved by the Ethics Committee, Nucleus of Collective Health Studies (protocol no. 2223-CEP/HUPE). One hundred fifty-four human mandibular first and second molars with completely separated roots, extracted for reasons not related to this study, were obtained from a pool of teeth. Roots were initially inspected by stereomicroscopy under 12× magnification to exclude teeth with any pre-existing craze lines or cracks. A digital radiograph in a buccolingual direction was taken to determine the curvature angle of the mesial root using an open source image analysis program (Fiji v.1.47n; Fiji, Madison, WI). Only teeth with a moderate curvature of the mesial root (ranging from 10◦–20◦) were selected. Teeth not patent to the canal length with a size 10 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer) were also discarded. The coronal portions and distal roots of all teeth were removed by using a low-speed saw (Isomet; Buhler Ltd, Lake Bluff, NY) with water cooling, leaving mesial roots with approximately 12 1 mm in length to prevent the introduction of confounding variables. As a result, 76 specimens were selected and stored in 0.1% thymol solution at 5◦C.

To attain an overall outline of the anatomic configuration of the mesial canals, specimens were prescanned in a relatively low isotropic resolution (70 mm) using a micro-CT scanner (SkyScan 1172; Bruker- microCT, Kontich, Belgium) at 70 kV and 114 mA. Based on this prescan set of images, 30 specimens with a type II Vertucci canal configuration system were selected. These specimens were scanned again at an isotropic resolution of 14.16 mm. Flat-field correction was taken before the scanning procedures to correct variations in the camera pixel sensitivity. Scanning was performed by 360◦ rotation around the vertical axis with a rotation step of 0.5◦, a camera exposure time of 7000 milliseconds, and frame averaging of 5. X-rays were filtered with a 1-mm-thick aluminum filter. Images were reconstructed with NRecon 1.6.3 software (Bruker-microCT) using 40% beam hardening correction and ring artifact correction of 10, resulting in the acquisition of 700–800 transverse cross-sections per tooth in a bitmap format.

Root Canal Preparation

A thin film of polyether impression material was used for coating the cement surface of roots to simulate the periodontal ligament, and each specimen was placed coronal-apically inside a custom-made epoxy resin holder (Ø 18 mm) to streamline further coregistration processes. Apical patency was determined by inserting a size 10 K-file into the root canal until its tip was visible at the apical foramen, and the working length (WL) was set 1.0 mm shorter of this measurement. After glide paths were established with a size 15 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer) up to the WL, the specimens were randomly assigned to 3 experimental groups (n = 10) according to the system used for the root canal preparation:

- Group A: Reciproc

- Group B: WaveOne

- Group C: BioRaCe

For all groups, irrigation was performed in exactly the same method using 40 mL of 5.25% sodium hypochlorite. Instruments were driven with the VDW Silver motor according to each manufacturer’s instructions, and a single experienced operator performed all preparations.

In group A, the R25 Reciproc instrument (25/0.08) was moved in the apical direction using a slow in-and-out pecking motion of about 3 mm in amplitude with a light apical pressure in a reciprocating motion until the WL was reached. After 3 pecking motions, the instrument was removed from the canal and cleaned. Then, the R40 Reciproc instrument (40/0.06) was used to the full WL following the same protocol. Group B was prepared with WaveOne Primary (25/0.08) and Large (40/0.08) instruments to the WL using the same technique as described in group A. In group C, preparation was performed in a crown-down manner with the BioRaCe system until the WL was reached using the following sequence: BR0 (25/0.08), BR1 (15/0.05), BR2 (25/0.04), BR3 (25/0.06), BR4 (35/0.04), and BR5 (40/0.04) instruments. After 4 steady strokes, the instrument was removed from the canal and cleaned.

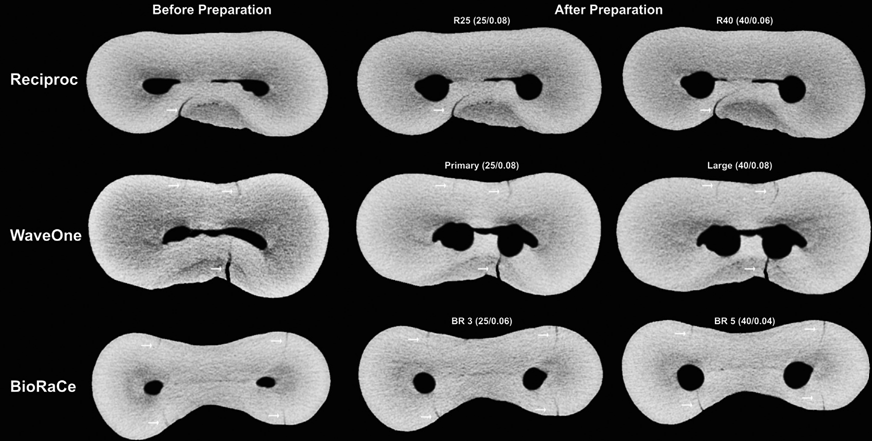

Two postoperative micro-CT scans of each specimen after canal preparation with instruments R25 and R40 in group A, WaveOne Primary and Large in group B, and BR3 and BR5 in group C were performed using the aforementioned parameters.

Dentinal Microcrack Evaluation

The image stacks of the specimens before and after canal preparation were coregistered by an automatic superimposition process based on the outer root contour using 1000 interactions with Seg3D v.2.1.4 software (SCI Institute’s National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences CIBC Center, Bethesda, MD). Then, the cross-section images of the mesial roots, from the furcation level to the apex (N = 65,340), were screened by 3 precalibrated examiners to identify the presence of dentinal microcracks. First, postoperative images were analyzed, and the cross-section number in which a dentin defect had been observed was recorded. Afterward, the preoperative corresponding cross-section image was also examined to verify the pre-existence of a dentinal defect. To validate the screening process, image analyses were repeated twice at 2-week intervals; in case of divergence, the image was examined together until reaching an agreement.

Results

Qualitative analysis showed the presence of dentinal microcracks in 8.72% (n = 5697), 11.01% (n = 7197), and 7.91% (n = 5169) of the cross-section images in groups A (Reciproc), B (WaveOne), and C (BioRaCe), respectively, from a total of 65,340 slices. Thus, 27.64% (18,063 slices) of the images showed some dentin defect. All dentinal defects identified in the analysis of both postoperative scans were already present in the corresponding preoperative images (Fig. 1). In other words, this means that no new microcrack was observed after biomechanical root canal preparation.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown a high-percentage frequency of dentinal defects caused by the mechanical preparation of root canals; however, the few studies that evaluated the incidence of dentinal defects after root canal preparation with reciprocating instruments showed contrasting and inconclusive results. Bürklein et al showed that root canal preparation with both rotary and reciprocating instruments resulted in dentinal defects, and, at the apical level, reciprocating files (Reciproc and WaveOne) produced significantly more incomplete dentinal cracks than full-sequence rotary systems (Mtwo and ProTaper). Conversely, using a similar methodology, Liu et al found that the ProTaper multiple-file rotary system caused more cracks on the apical root surface or in the canal wall than single-file rotary (OneShape) or reciprocating (Reciproc) systems. Ashwinkumar et al also observed that canal preparation with ProTaper rotary files was associated with significantly more micro-cracks than the WaveOne reciprocating system.

The current results markedly contrast with previous studies considering that the dentinal microcracks observed in the postoperative images were in fact already present in the corresponding preoperative image, which clearly point out that cleaning and shaping procedures using either rotary or reciprocating systems were not associated with their formation. This discrepancy in the results certainly is partially explained by the differences in the methodologic design. Evidence in the current literature correlating mechanical preparation and the development of dentinal defects is based only on root sectioning methods and direct observation by optical microscopy. These methods undoubtedly have a noteworthy drawback related to the destructive nature of the experiment reported in a previous work (unpublished data, 2014). Despite the fact that the control groups, which used unprepared teeth, seemed to validate these results, because no dentinal defects could be detected, this sort of control does not take into account the potential damage produced by the interplay among 3 sources of stresses on the root dentin:

- The mechanical preparation

- The chemical attack with sodium hypochlorite–based irrigation

- The sectioning procedures

In the present study, micro-CT image technology was used to evaluate the presence of dentinal defects at baseline and after different root canal enlargements using either rotary or reciprocating instruments. This highly accurate and nondestructive method allows the assessment of the specimens before instrumentation; thus, pre-existing cracks are detected, and it is possible to precisely state in which region they were created and/or propagated. It is of note that someone can argue that any dentin damage from pre- to postoperative conditions may occur and not be observable because it is below the spatial resolution threshold of the micro-CT system. However, the full extension of dentinal microcracks visualized under conventional stereomicroscopy also could be observed through mCT cross-sectional images, which confirms the reliability of this contemporary technology for detecting dentin defects (unpublished data, 2014).

The results of the present study revealed the presence of dentinal microcracks in 27.64% of the preoperative images. On the other hand, control groups in previous studies have shown no dentinal defect, and so, the question of why such a high level of preoperative cracks was achieved in the current study is raised. The main reason is the evaluation method because micro-CT imaging has a much higher definition than stereomicroscopy. Besides, and even more importantly, although conventional sectioning techniques allowed the evaluation of only a few slices per tooth with the real possibility of missing several previous defects along the root, hundreds of slices can be analyzed per tooth with micro-CT imaging. Another methodologic dissimilarity was related to the sample selection. Although most of the previous studies used single-rooted teeth, in the present study, mesial canals of mandibular molars were used. These canals have a constricted anatomic configuration, which could result in more stress on the dentinal surface during mechanical preparation and, consequently, increase the potential to produce cracks. However, even with this anatomic feature, no instrumentation-driven dentinal defect was observed.

It has been stated that the potential to promote dentinal defects may be related to the design of the instrument. According to Bier et al, an increased file taper can contribute to the formation of dentinal defects because of the increased stress on the canal walls. In the present study, variations in the instrument’s design were not related with cracks formation even when the canals were prepared up to size

40. This is an important finding because there is evidence that a larger apical preparation would allow for a greater reduction of intracanal bacteria load and hard tissue debris as a consequence of a more effective irrigation. It is worth noting that in the present study, root canal instrumentation was performed 1 mm short of the apical foramen. Because the incidence of apical root cracks could be related to different instrumentation lengths, further micro-CT studies should be performed to evaluate whether a distinct instrumentation level triggers the incidence of dentinal defects.

Under the condition of this study, it is possible to conclude that there is a lack of causal relationship between dentinal microcracks and root canal preparation with Reciproc, WaveOne, and BioRaCe systems. Future micro-CT studies evaluating the incidence of microcracks after other endodontic procedures such as filling, retreatment, and post preparation are necessary to provide a better understanding of dentinal microcracks formation related to intracanal procedures.

Authors: Gustavo De-Deus, Emmanuel João Nogueira Leal Silva, Juliana Marins, Erick Souza, Aline de Almeida Neves, Felipe Gonçalves Belladonna, Haimon Alves, Ricardo Tadeu Lopes, Marco Aurelio Versiani

References:

- Yared G. Canal preparation using only one Ni-Ti rotary instrument: preliminary observations. Int Endod J 2008;41:339–44.

- Perez-Higueras JJ, Arias A, de la Macorra JC. Cyclic fatigue resistance of K3, K3XF, and Twisted File nickel-titanium files under continuous rotation or reciprocating motion. J Endod 2013;39:1585–8.

- Kiefner P, Ban M, De-Deus G. Is the reciprocating movement per se able to improve the cyclic fatigue resistance of instruments? Int Endod J 2014;47:430–6.

- Bürklein S, Hinschitza K, Dammaschke T, Schäfer E. Shaping ability and cleaning effectiveness of two single-file systems in severely curved root canals of extracted teeth: Reciproc and WaveOne versus Mtwo and ProTaper. Int Endod J 2012;45: 449–61.

- Siqueira JF Jr, Alves FRF, Versiani MA, et al. Correlative bacteriologic and micro– computed tomographic analysis of mandibular molar mesial canals prepared by Self-Adjusting File, Reciproc, and Twisted File systems. J Endod 2013;39: 1044–50.

- Versiani MA, Steier L, De-Deus G, et al. Micro–computed tomography Fstudy of oval-shaped canals prepared with the Self-adjusting File, Reciproc, WaveOne, and Protaper Universal systems. J Endod 2013;39:1060–6.

- Bürklein S, Benten S, Schäfer E. Shaping ability of different single-file systems in severely curved root canals of extracted teeth. Int Endod J 2013;46:590–7.

- Bürklein S, Tsotsis P, Schäfer E. Incidence of dentinal defects after root canal preparation: reciprocating versus rotary instrumentation. J Endod 2013;39:501–4.

- Sathorn C, Palamara JE, Messer HH. A comparison of the effects of two canal preparation techniques on root fracture susceptibility and fracture pattern. J Endod 2005;31:283–7.

- Shemesh H, van Soest G, Wu MK, Wesselink PR. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures with optical coherence tomography. J Endod 2008;34:739–42.

- Tamse A, Fuss Z, Lustig J, Kaplavi J. An evaluation of endodontically treated vertically fractured teeth. J Endod 1999;25:506–8.

- Toure B, Faye B, Kane AW, et al. Analysis of reasons for extraction of endodontically treated teeth: a prospective study. J Endod 2011;37:1512–5.

- Keleş A, Alcin H, Kamalak A, Versiani MA. Oval-shaped canal retreatment with self-adjusting file: a micro-computed tomography study. Clin Oral Investig 2014;18: 1147–53.

- Versiani MA, Pécora JD, Sousa-Neto MD. Flat-oval root canal preparation with self-adjusting file instrument: a micro-computed tomography study. J Endod 2011;37: 1002–7.

- De-Deus G, Roter J, Reis C, et al. Assessing accumulated hard-tissue debris using micro-computed tomography and free software for image processing and analysis. J Endod 2014;40:271–6.

- Peters OA, Laib A, Rüegsegger P, Barbakow F. Three-dimensional analysis of root canal geometry by high-resolution computed tomography. J Dent Res 2000;79:1405–9.

- Schneider SW. A comparison of canal preparations in straight and curved root canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1971;32:271–5.

- Vertucci FJ. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1984;58:589–99.

- Liu R, Hou BX, Wesselink PR, et al. The incidence of root microcracks caused by 3 different single-file systems versus the ProTaper system. J Endod 2013;39:1054–6.

- Bier CA, Shemesh H, Tanomaru-Filho M, et al. The ability of different nickel-titanium rotary instruments to induce dentinal damage during canal preparation. J Endod 2009;35:236–8.

- Shemesh H, Bier CA, Wu MK, et al. The effects of canal preparation and filling on the incidence of dentinal defects. Int Endod J 2009;42:208–13.

- Adorno CG, Yoshioka T, Suda H. The effect of root preparation technique and instrumentation length on the development of apical root cracks. J Endod 2009;35: 389–92.

- Yoldas O, Yilmaz S, Atakan G, et al. Dentinal microcrack formation during root canal preparations by different NiTi rotary instruments and the Self-Adjusting File. J Endod 2012;38:232–5.

- Barreto MS, Moraes Rdo A, Rosa RA, et al. Vertical root fractures and dentin defects: effects of root canal preparation, filling, and mechanical cycling. J Endod 2012;38: 1135–9.

- Ashwinkumar V, Krithikadatta J, Surendran S, Velmurugan N. Effect of reciprocating file motion on microcrack formation in root canals: an SEM study. Int Endod J 2014; 47:622–7.

- Liu R, Kaiwar A, Shemesh H, et al. Incidence of apical root cracks and apical dentinal detachments after canal preparation with hand and rotary files at different instrumentation lengths. J Endod 2013;39:129–32.

- Fornari VJ, Silva-Sousa YT, Vanni JR, et al. Histological evaluation of the effectiveness of increased apical enlargement for cleaning the apical third of curved canals. Int Endod J 2010;43:988–94.

- Siqueira JF Jr. Reaction of periradicular tissues to root canal treatment: benefits and drawbacks. Endod Top 2005;10:123–47.