Assessing Accumulated Hard-tissue Debris Using Micro–computed Tomography and Free Software for Image Processing and Analysis

Abstract

Introduction: The accumulation of debris occurs after root canal preparation procedures specifically in fins, isthmus, irregularities, and ramifications. The aim of this study was to present a step-by-step description of a new method used to longitudinally identify, measure, and 3-dimensionally map the accumulation of hard-tissue debris inside the root canal after biomechanical preparation using free software for image processing and analysis.

Methods: Three mandibular molars presenting the mesial root with a large isthmus width and a type II Vertucci’s canal configuration were selected and scanned. The specimens were assigned to 1 of 3 experimental approaches: (1) 5.25% sodium hypochlorite + 17% EDTA, (2) bidistilled water, and (3) no irrigation. After root canal preparation, high- resolution scans of the teeth were accomplished, and free software packages were used to register and quantify the amount of accumulated hard-tissue debris in either canal space or isthmus areas.

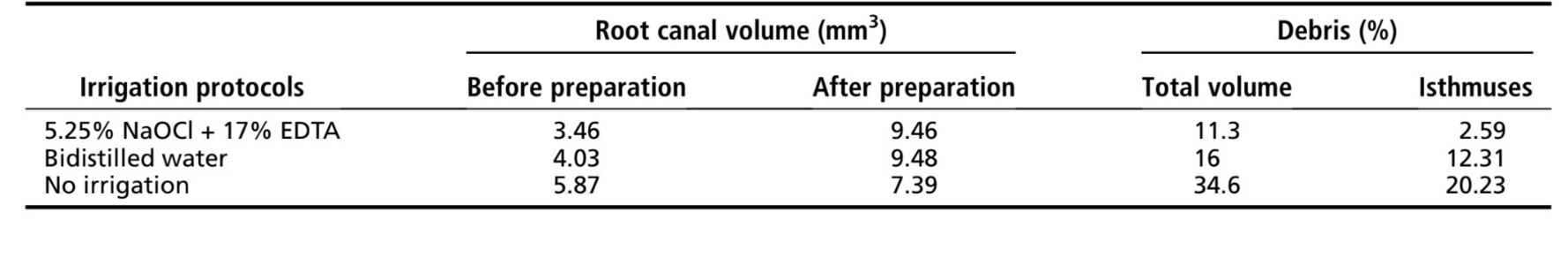

Results: Canal preparation without irrigation resulted in 34.6% of its volume filled with hard-tissue debris, whereas the use of bidistilled water or NaOCl followed by EDTA showed a reduction in the percentage volume of debris to 16% and 11.3%, respectively. The closer the distance to the isthmus area was the larger the amount of accumulated debris regardless of the irrigating protocol used.

Conclusions: Through the present method, it was possible to calculate the volume of hard-tissue debris in the isthmuses and in the root canal space. Free-software packages used for image reconstruction, registering, and analysis have shown to be promising for end-user application. (J Endod 2014;40:271–276)

Since the first description of a smeared layer on instrumented root dentin, the concept of a smear layer has played a pivotal role in endodontic research and practice. The smear layer has been defined as a surface film of debris retained on dentin and other surfaces after instrumentation with either rotary instruments or endodontic files. It consists of dentin particles, remnants of vital or necrotic pulp tissue, bacterial components, and retained irrigant. Unfortunately, the results of previous studies were partially contradictory, and most of the clinical recommendations were based only on limited descriptive or semiquantitative in vitro scanning electron microscopic evaluations. On the other hand, Paqué et al reopened an interesting discussion about the substantial accumulation of debris occurring after biomechanical preparation specifically in fins, isthmuses, irregularities, and ramifications of the complex root canal network. Hard-tissue debris accumulation has been considered a side effect of the cleaning and shaping procedures and may be more clinically relevant than the smear layer because its sizable amount could easily harbor bacteria biofilm from the disinfection procedures. The assessment of hard-tissue debris accumulation has been made possible through the combination of nondestructive micro–computed tomography (CT) imaging and the development of robust image analysis and processing software. Through micro-CT imaging, teeth can be scanned before and after cleaning and shaping procedures, and, with the aid of proper software, the image volumes resulting from both scanning procedures can be geometrically coregistered (ie, different sets of data can be transformed and integrated into 1 coordinate system).

This allows, to some measure, the identification of the dentin debris that was packed into the original root canal space after preparation. The rationale behind this approach has a simple basis, which was described first by Paqué et al and was recently well defined by Robinson et al as ‘‘pixels that were occupied by air and then became dentine must be debris.’’

Interesting findings of the effect of current cleaning and shaping procedures on the accumulation of hard-tissue debris has been shown in recent studies.

- EDTA and passive ultrasonic irrigation reduced hard-tissue debris accumulation, but approximately 50% of the debris still remained in the root canal space.

- The use of a hypochlorite-compatible chelator enabled reduction of hard-tissue debris accumulation.

- Self-adjusting file systems (ReDent-Nova, Ra’anana, Israel) resulted in less hard-tissue debris accumulated in isthmus-containing root canal systems than rotary instrumentation with ProTaper (Dentsply/Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) and needle/syringe irrigation.

These findings need to be underscored because they were provided by methodologically sound experiments using micro-CT technology and image analysis. Thus, a point worth discussing is the recent methodologic shift in the study of hard-tissue debris accumulation. Therefore, some concerns regarding micro-CT technology must be pointed out considering that this is a high-cost, labor-intensive, and time-consuming procedure that demands an extended learning curve to get the required expertise to extract quantitative data. One of the reasons for the high cost of experimental procedures using this technology is related to the typically expensive proprietary software packages. This is one of the points that prevent the worldwide dissemination of this useful methodology.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to present a step-by-step description of a new method used to longitudinally identify, measure, and 3-dimensionally map the accumulation of hard-tissue debris inside the root canal space after biomechanical preparation using free software for image processing and analysis. Its advantages over proprietary image analysis software packages and its limitations are also carefully addressed.

Materials and Methods

Teeth Selection Criteria

This study was revised and approved by the Ethics Committee, Nucleus of Collective Health Studies (protocol no. 2223-CEP/HUPE). One hundred twenty human mandibular first and second molars with completely separated roots were obtained from a pool of extracted teeth. Teeth were extracted for reasons not related to this study and initially selected on the basis of digital radiographs taken in buccolingual direction to detect any possible root canal obstruction and to determine the curvature angle of the mesial root as described by Schneider. The curvature angle was measured using an open source image analysis program (Fiji v.1.47n; Madison, WI), and only teeth with a mesial root with moderate curvature (ranging from 10◦–20◦) were selected. In addition, the inclusion criteria comprised only molars in which the final apical gauging of the mesial canals allowed for a size 10 hand file (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) to be placed to the working length. Moreover, the length of the specimens was standardized between 20 and 22 1 mm to prevent the introduction of confounding variables, which might contribute to variations in the preparation procedures. As a result, 52 mandibular molars were selected and stored in 0.1% thymol solution at 5◦C.

To attain an overall outline of root canal anatomy, these teeth were prescanned in a relatively low isotropic resolution (70 mm) using a micro–computed tomography scanner (SkyScan 1172; Bruker-microCT, Kontich, Belgium) at 70 kV and 114 mA. Based on the 3-dimensional (3D) models of this prescan set of images, 37 mandibular molars presenting a mesial root with a type II Vertucci’s canal configuration system with a large isthmus width between the mesial canals were selected. After resection of the distal root at the furcation level, 3 teeth were randomly selected for the presen study and scanned again at an isotropic resolution of 14.16 mm. The other teeth were kept for further use.

Root Canal Preparation and Irrigation

The apexes of the 3 teeth were sealed with hot glue and embedded in polyvinyl siloxane to simulate the effect of apical gas entrapment in a closed canal system during root canal preparation. Then, to further streamline coregister processes, each tooth was placed coronal apically inside a custom-made epoxy resin holder (Ø = 18 mm) to smoothly fit it into the sample holder of the micro-CT device The specimens were randomly assigned to 1 of the 3 experimental approaches, and a flip of a coin was used to define which teeth would be treated with the following irrigation protocols:

- 5.25% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) + 17% EDTA

- Bidistilled water

- No irrigation (positive control)

Teeth were prepared using a nickel-titanium reciprocation technique in a standardized way. Teeth were accessed, and the root canal patency was confirmed by inserting a size 10 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer) through the apical foramen before and after completion of root canal preparation. The working length was established by deducting 1 mm from the canal length. Reciproc R25 (VDW GmbH, Munich, Germany) was introduced into the canal until resistance was felt and then activated in a reciprocating motion generated by a 6:1 contra-angle handpiece (Sirona, Bensheim, Germany) powered by an electric motor (VDW Silver; VDW GmbH, Munich, Germany) using the preset configuration ‘‘Reciproc ALL.’’ The instrument was moved in the apical direction using an in-and- out pecking motion of about 3 mm in amplitude with a light apical pressure. After 3 pecking motions, the instrument was removed from the canal and cleaned. A single operator with expertise in performing root canal treatment using reciprocating techniques performed all preparations.

For irrigation protocols 1 (5.25% NaOCl + 17% EDTA) and 2 (bidistilled water), irrigants were continuously delivered by a VATEA peristaltic pump (ReDent-Nova, Ra’anana, Israel) at a 2 mL/min rate connected to a 30-G Endo-Eze Tip (Ultradent Products Inc, South Jordan, UT) inserted into the canal without binding up to 2 mm from the apical foramen. Aspiration was performed with a SurgiTip (Ultradent Products Inc) attached to a high-speed suction pump. Between each preparation step, root canals were irrigated with 2 mL irrigant for 1 minute. As a result, a total volume of 20 mL 5.25% NaOCl (protocol 1) and bidistilled water (protocol 2) was used per root canal during biomechanical preparation. After root canal preparation, an additional rinse with 20 mL of the irrigant was performed for 10 minutes. Thus, in each protocol, a total volume of 40 mL irrigant was used per canal for a total time of 30 minutes. After this step, the smear layer was removed with 3 mL 17% EDTA (pH = 7.7) delivered at a 1-mL/min rate for 3 minutes. Then, all canals were dried with absorbent paper points (Dentsply Maillefer). For protocol 3, mesial canals were prepared without irrigant solution.

Micro-CT Scans

High-resolution scans, before and after root canal preparation, were accomplished per tooth using the same selected parameters. The teeth were scanned (SkyScan 1172) at 70 kV, 114 mA, and an isotropic pixel size of 14.16 mm. The scanning was performed by 360◦ rotation around the vertical axis with a camera exposure time of 7,000 milliseconds, rotation step of 0.5◦, and frame averaging of 5. X-rays were filtered with a 1- mm aluminium filter. A flat-field correction was taken before the scanning procedures to correct for variations in the pixel sensitivity of the camera. Images were reconstructed using NRecon v.1.6.3 (Brucker-microCT) with a beam hardening correction of 40% and ring artifact correction of 10, resulting in the acquisition of 700–800 transverse cross-sections per tooth in a bitmap format. The volume of interest was selected extending from the furcation level to the apex of the mesial root.

Quantitative Image Analysis

For the quantitative analysis, the original grayscale cross-sectional images of the roots before and after preparation were processed with an interactive segmentation threshold to separate dentin and debris from the root canal space using the Seg3D v.2.1.4 software interface (National Institutes of Health Center for Integrative Biomedical Computing, University of Utah Scientific Computing and Imaging Institute, Salt Lake City, UT). This process entails choosing the range of gray levels necessary to recognize regions of a given image dividing it into its specific component parts of interest. The final result is a binary image composed only of black or white pixels in which the black pixels represent the empty spaces and the white pixels the object of interest. Then, a label mask was applied to the segmented regions of interest and saved as colored opaque layers. Using the same software, the label mask image stacks of the root, from the teeth before and after canal preparation, were selected and coregistered by an automatic superimposition process based on the outer root contour using 1,000 interactions. To validate this process, nonprepared teeth were submitted twice to the scanning process being removed and reinserted in the sample holder of the micro-CT device. Afterward, the difference between pre- and postscanning datasets achieved by a morphologic subtraction operation showed a computational error of only 1% (~2 voxels), which confirmed the reliability of the registration process.

The label masks of the registered datasets of each tooth were imported into the Fiji software and normalized. In the normalization procedure, all the pixel values in the mask files were ranked and divided into a number of quantiles. After that, each of the values in a given quantile was replaced with the mean value in that quantile, resulting in a very similar distribution of histogram values across all the images.

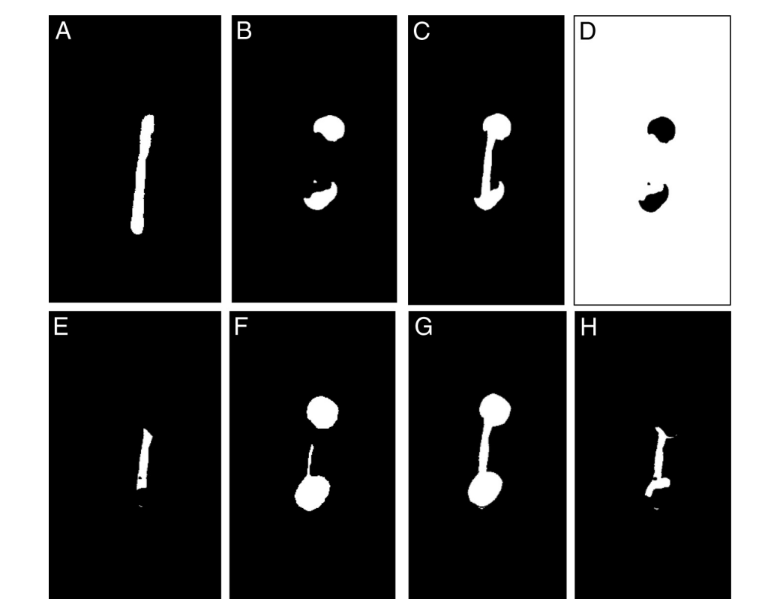

Afterward, the canal space was segmented as a result of an automatic bitwise operation of exception between the root image sequence with segmented dentine, and this very same sequence was duplicated and inverted. The sequence of images resulting from this operation was further used to identify the accumulated hard-tissue debris by means of morphologic operations. Quantification of debris was performed by the difference between nonprepared and prepared root canal space using postprocessing procedures in the Fiji software (Fig. 1A–H). The presence of a material with density similar to dentin in regions previously occupied by air in the nonprepared root canal space was considered debris and quantified by intersection between images before and after canal instrumentation. The identification of hard-tissue debris was a result from the intersection (AND) of the image of the prepared root canal without any debris and the same image inverted but with debris inside. The volume of matched canal space before and after preparation and the total volume of accumulated hard-tissue debris were calculated in absolute values.

The result of A or B; prepared canal with no debris; the nonprepared canal does not have it. (D) An inverted image of B. (E) The result of C and D; the common

areas represent the empty spaces that were filled postpreparation. (F–H) Total debris. (F) Segmented prepared canal without debris. (G) The result of F or C. (H) The result of G and D; debris in isthmuses and in the instrumented canal space.

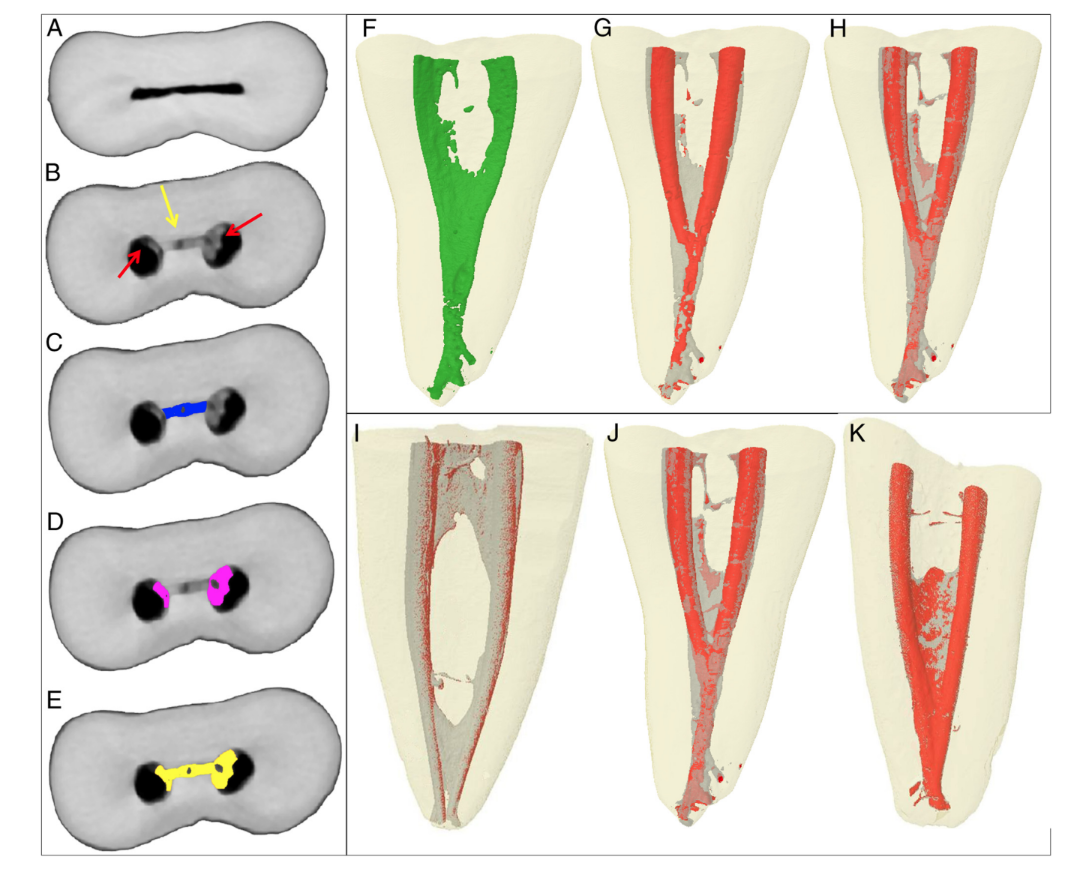

Subsequently, the stack of images obtained after debris quantification (Fig. 2A–E) was 3-dimensionally rendered using a plug-in 3D viewer (Internationale Medieninformatik; HTW Berlin, Berlin, Germany). Tridimensional models of the nonprepared canal, prepared canal, and total of debris were rendered (Fig. 2F–H). CTVol v.2.2.1 software (Bruker-microCT) was used for visualization and qualitative evaluation of the 3D models.

Results

It was possible to identify and measure the accumulated hard-tissue debris after preparation in the mesial root canals for all tested protocols (Fig. 2I–K). Table 1 shows the percentage volume of accumulated hard tissue after the preparation of mesial canals of mandibular molars using different irrigation protocols. Root canal preparation without irrigation (positive control group) resulted in 34.6% of its volume filled with hard-tissue debris, whereas the use of bidistilled water or 5.25% NaOCl followed by 17% EDTA showed a reduction in the percentage volume of debris to 16% and 11.3%, respectively; this was clearly observed in the 3D models in Figure 2. This reduction was also observed when the isthmus area was separately analyzed.

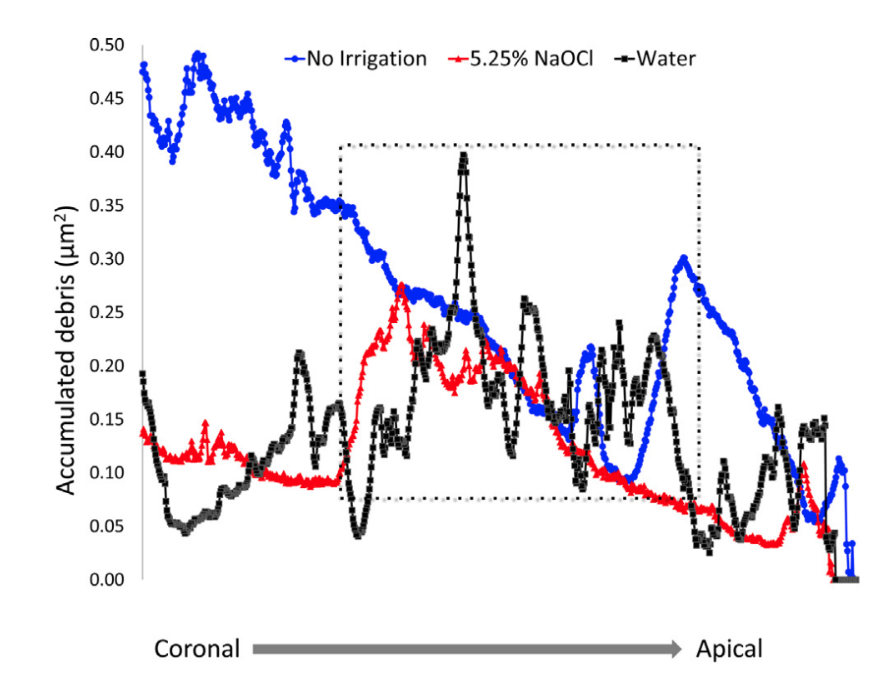

After qualitative evaluation of the 3D models and cross-sections of the specimens, it was possible to observe that hard-tissue debris accumulated not only in the isthmuses areas but also in irregularities of the dentinal walls (Fig. 2D and G), underscoring that this was a pattern along the entire length of the root canal. The distribution of the accumulated hard-tissue debris along the root canal levels is shown in the graph in Figure 3.

Discussion

In endodontics, nondestructive micro-CT technology has been successfully used for measuring debris in ex vivo experiments. Through the present method, it was possible to calculate the volume of accumulated hard-tissue debris in the isthmuses and in the instrumented root canal space in a separated way (Fig. 2A–E). The ability to independently assess the debris either in the noninstrumented isthmus area or in the instrumented root canal space is suitable inasmuch as it enables understanding the effect of a given preparation technique or irrigating protocol in each one of these areas or in the root canal system as a whole. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is an innovative aspect compared with previous studies in which the measurements were limited to the isthmus area. It can be assumed that the image processing and analysis used in the previous studies were unable to discern between prepared root canal space and densely packed accumulated debris. This may explain why the accumulated debris was superimposed on the original root canal anatomy rather than on the anatomy after preparation.

According to some previous reports, sodium hypochlorite solution combined with different irrigation protocols was unable to completely remove debris from hard-to-reach root canal areas such as isthmuses, fins, and irregularities; the current results corroborate these findings, which can be easily observed in the 3D models of the prepared teeth (Fig. 2). In this initial report, measurements were performed only to show that the method is able to reliably calculate the accumulated hard-tissue debris both in the isthmus areas and in the prepared root canal; this was the reason why only 3 teeth were used, and, thus, no statistical comparisons were made. Even so, it may be assumed that canals irrigated with bidistilled water showed a higher tendency to retain debris compared with the conventional irrigation protocol even though the same flow rate of the solution and the same irrigation time were applied in both cases (Fig. 2I–K). The overall purpose of this study was to test whether a free software approach method would be effective in measuring the accumulation of debris and also to point out differences in the outcome measurement. For this reason, no sizeable experimental groups were created, and just 3 teeth were used. Therefore, apart from the quantitative data, a qualitative descriptive analysis was performed, and it was enough to display the differences among the 3 protocols because the size of the tested effect is large and strong.

As expected, the percentage volume of hard-tissue debris accumulated was higher in the nonirrigated canals (34.6%) and in the canals irrigated with bidistilled water (16%) in comparison with the conventional irrigation protocol, which markedly showed less remaining debris (11.3%). The tissue-dissolution capacity of aqueous hypochlorite combined with EDTA may explain the lowest percentage of remaining debris in the root canal. Similarly, at the isthmus area, the lowest percentage volume of debris was also observed when canals were irrigated with 5.25% NaOCl plus 17% EDTA. As expected, the nonirrigated tooth showed notably more accumulated debris, certainly because of the lack of the liquid flow effect. This is in line with a classic study Baker et al, which found 70% more debris when canal instrumentation was performed without any irrigation.

It is a noteworthy finding that the percentage volume of debris in the present study was lower than those previously reported. This is indeed expected and can be explained because in those studies the volume of the root canal before preparation was used for comparison, whereas in the current study the reference parameter was the volume of the canal after preparation. The assumption behind this new approach is based on the rationale that the final canal volume is the real volume of the canal after mechanical enlargement.

Typically, proprietary software packages are quite expensive, and their availability to the general research community is limited. Moreover, most of them do not fulfill special functions needed for endodontic research. For this article, image processing and visualization software selection were based on 1 main constraint of being freely available. Briefly, the NRecon package (Brucker micro-CT) was used to reconstruct cross-sectional images from tomography projection images. Then, Seg3D software (National Institutes of Health Center for Integrative Biomedical Computing) was used to register datasets before and after root canal preparation. Finally, the amount of debris was calculated with Fiji software. This is an important aspect and may benefit research groups of all budgets. As a consequence, free software may help to spread the use of 3D reconstruction and micro-CT methods in general.

On one hand, software used herein has many automatic tools for data processing and registration that make image analysis a less labor-intensive and time-consuming procedure. On the other hand, this range of automatic tools may lead to some procedural errors reflecting on the final measurements. Therefore, special attention was directed toward the accuracy of the registration process performed with the Seg3D software and the accuracy of the digital image analysis and processing with Fiji software through the use of aluminum ball bearings. Nevertheless, contrary to Robinson et al’s findings, the computational error for the largest balls was lower for all the samples, whereas the smallest ones showed equal results for volume. Consequently, the measurements performed by Fiji software were considered reliable for quantifying volume even in small samples.

A huge effort was also made to ensure the creation of a robust baseline concerning root canal length and curvature as well as the anatomic configuration. This is a critical step with the purpose of minimizing the effect of anatomy on the final results. In the present study, only canals with type II Vertucci’s classification were chosen to ensure the presence of isthmuses and communication between the mesial canals as well as hard-to-reach areas where tissue debris tends to accumulate.

A closed-end canal design was used to mimic in vivo settings in which the foramen is enclosed within alveolar bone and periodontal ligament; according to Tay et al, the closed canal system produces gas entrapment, which often prevents the irrigant from reaching the last apical millimeters of the canal space. This same approach was used in other studies as well, which stresses the scientific concern in understanding the effect of gas entrapment on the irrigating protocols.

Isthmuses connecting multiple canals are the type of anatomic configuration that presents a clinical challenge directly related to the irrigating protocols because all preparation techniques often leave behind accumulated hard- and soft-tissue remnants as well as microorganisms in these hard-to-reach areas. To improve irrigant delivery and flow, different devices and solutions are available. In this study, 5.25% NaOCl solution followed by 17% EDTA was used because it is the most commonly used irrigating solution worldwide and it has properties of being an efficient solvent of inorganic and organic tissue. Bidistilled water was used as a control irrigating protocol presumed to be less effective because water is an inert solution and, thus, only the physical effect of irrigant flow would be expected. Moreover, the time (30 minutes) and the total volume (40 mL) of irrigants were carefully observed to ensure comparable physical irrigation conditions among these experimental protocols, reproducing a sound clinical standard. Following Paqué et al’s study, no irrigation protocol was used herein; thus, it was possible to ensure a standard for comparison with a huge debris packing originated from the direct mechanical action of the instrument to the dentinal walls and also without counting on any flow effect of the irrigant solution.

Once it is known that cleaning and shaping are relevant processes for the outcome of endodontic therapy, further experiments are necessary to assess antidebris strategies and to test the potential correlation between the accumulated hard-tissue debris and the penetration of the irrigating solution, microbial survival inside complex root canal anatomy, and root canal filling.

In conclusion, despite the long learning curve required for dealing with these new imaging technologies, the free software packages used for image reconstruction, registering, and analysis in the present study have shown to be promising for end-user application in contemporary endodontic research.

Authors: Gustavo De-Deus, Juliana Marins, Aline de Almeida Neves, Claudia Reis, Sandra Fidel, Marco A. Versiani, Haimon Alves, Ricardo Tadeu Lopes, Sidnei Paciornik

References:

- McComb D, Smith DC. A preliminary scanning electron microscopic study of root canals after endodontic procedures. J Endod 1975;1:238–42.

- De-Deus G, Reis C, Paciornik S. Critical appraisal of published smear layer-removal studies: methodological issues. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Endod 2011;112: 531–43.

- Glossary of Endodontics Terms, 8th ed. Chicago, IL: American Association of Endodontists; 2012.

- Paqué F, Laib A, Gautschi H, et al. Hard-tissue debris accumulation analysis by high-resolution computed tomography scans. J Endod 2009;35:1044–7.

- Robinson JP, Lumley PJ, Claridge E, et al. An analytical Micro CT methodology for quantifying inorganic dentine debris following internal tooth preparation. J Dent 2012;40:999–1005.

- Versiani MA, Leoni GB, Steier L, et al. Micro–computed tomography study of oval-shaped canals prepared with the Self-adjusting File, Reciproc, WaveOne, and Pro-Taper Universal Systems. J Endod 2013;39:1060–6.

- Paqué F, Boessler C, Zehnder M. Accumulated hard tissue debris levels in mesial roots of mandibular molars after sequential irrigation steps. Int Endod J 2010; 44:148–53.

- Paqué F, Rechenberg D-K, Zehnder M. Reduction of hard-tissue debris accumulation during rotary root canal instrumentation by etidronic acid in a sodium hypochlorite irrigant. J Endod 2012;38:692–5.

- Paqué F, Al-Jadaa A, Kfir A. Hard-tissue debris accumulation created by conventional rotary versus self-adjusting file instrumentation in mesial root canal systems of mandibular molars. Int Endod J 2012;45:413–8.

- Schneider SW. A comparison of canal preparations in straight and curved root canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Endod 1971;32:271–5.

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature methods 2012;9:676–82.

- Vertucci FJ. Root canal morphology and its relationship to endodontic procedures. Endod Topics 2005;10:3–29.

- Susin L, Liu Y, Yoon JC, et al. Canal and isthmus debridement efficacies of two irrigant agitation techniques in a closed system. Int Endod J 2010;43: 1077–90.

- Tay FR, Gu LS, Schoeffel GJ, et al. Effect of vapor lock on root canal debridement by using a side-vented needle for positive-pressure irrigant delivery. J Endod 2009;36: 745–50.

- Peters OA, Boessler C, Paqué F. Root canal preparation with a novel nickel-titanium instrument evaluated with micro-computed tomography: canal surface preparation over time. J Endod 2010;36:1068–72.

- Peters OA. Current challenges and concepts in the preparation of root canal systems: a review. J Endod 2004;30:559–67.

- Gao Y, Peters OA, Wu H, et al. An application framework of three-dimensional reconstruction and measurement for endodontic research. J Endod 2009;35:269–74.

- Johnson M, Sidow SJ, Looney SW, et al. Canal and isthmus debridement efficacy using a sonic irrigation technique in a closed-canal system. J Endod 2012;38: 1265–8.

- Baker NA, Eleazer PD, Averbach RE, et al. Scanning electron microscopic study of the efficacy of various irrigating solutions. J Endod 1975;1:127–35.

- Peters OA, Peters CI, Schönenberger K, et al. ProTaper rotary root canal preparation: effects of canal anatomy on final shape analysed by micro CT. Int Endod J 2003;36:86–92.

- Versiani MA, P´ecora JD, Sousa-Neto MD. Microcomputed tomography analysis of the root canal morphology of single-rooted mandibular canines. Int Endod J 2013;46: 800–7.

- De Pablo OV, Estevez R, Péix Sánchez M, et al. Root anatomy and canal configuration of the permanent mandibular first molar: a systematic review. J Endod 2010;36: 1919–31.

- Adcock JM, Sidow SJ, Looney SW, et al. Histologic evaluation of canal and isthmus debridement efficacies of two different irrigant delivery techniques in a closed system. J Endod 2011;37:544–8.

- Parente JM, Loushine RJ, Susin L, et al. Root canal debridement using manual dynamic agitation or the EndoVac for final irrigation in a closed system and an open system. Int Endod J 2010;43:1001–12.

- Gu Li-sha, Kim Jong Ryul, Ling Junqi, et al. Review of contemporary irrigant agitation techniques and devices. J Endod 2009;35:791–804.

- Saleh IM, Ruyter IE, Haapasalo M, et al. Bacterial penetration along different root canal filling materials in the presence or absence of smear layer. Int Endod J 2008;41:32–40.

- Siqueira JJ, Alves FR, Versiani MA, et al. Correlative bacteriologic and micro–computed tomographic analysis of mandibular molar mesial canals prepared by SAF, Reciproc, and Twisted File systems. J Endod 2013;39: 1044–50.

- De-Deus G, Reis C, Beznos D, et al. Limited ability of three commonly used thermo-plasticized gutta-percha techniques in filling oval-shaped canals. J Endod 2008;34: 1401–5.

/public-service/media/default/147/bjsSM_65311952dfadf.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/158/GMj69_65311b2333f75.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/148/ix2WY_6531196adc6ec.jpg)

/public-service/media/default/145/GbhGY_65311921a3b65.jpg)