Micro-CT study on root and canal morphology of single-rooted mandibular first premolars with radicular grooves

Abstract

Aim: To evaluate the external and internal morphologies of single-rooted mandibular first premolars with radicular grooves from a Brazilian subpopulation, using micro-CT technology.

Methodology: Seventy mandibular first premolars with RG were scanned at a resolution of 22.9 μm. Each tooth was examined regarding the morphology of the roots and the length, depth and percentage frequency location of the RG. Volume, surface area and Structure Model Index (SMI) of the canals were measured for the full root length, while two-dimensional parameters (area, roundness, form factor, and diameter) and the percentage frequency of canal orifices were evaluated at 1, 2, and 3 mm levels from the apical foramen, The number of accessory canals, the internal and external dentinal thickness, and the cross-sectional appearance of the canal in different levels of the root were also recorded. Configuration of the root canals was classified according to Vertucci’s system.

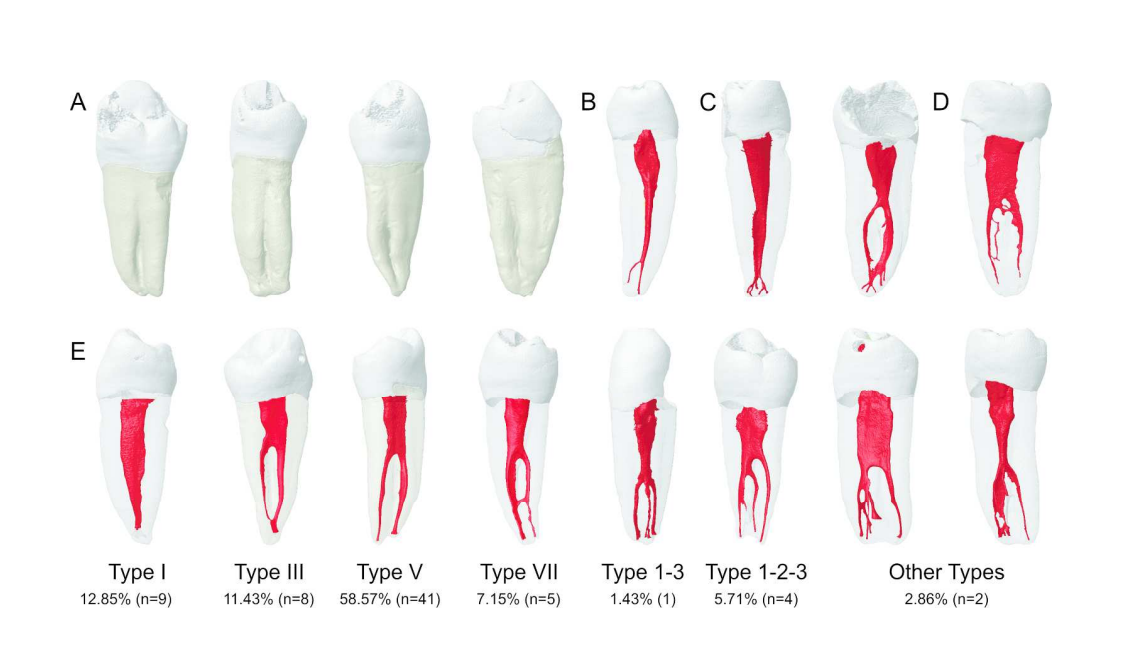

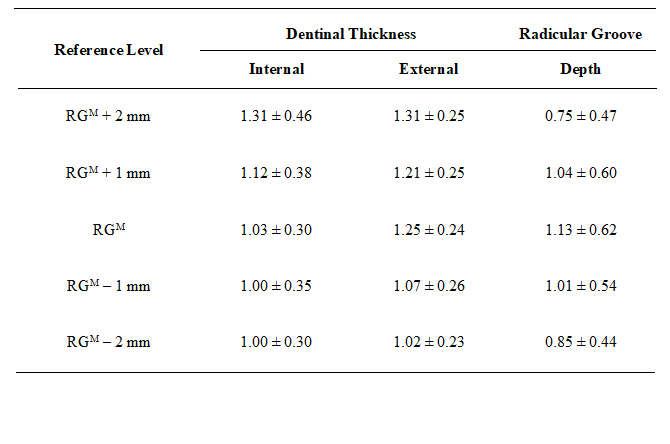

Results: Expression of deep grooves (grades 3 and 4) was observed in 25.71% of the sample and most of them were located at the mesial aspect of the root. Mean lengths of the root and RG were 13.43 mm and 8.5 mm, respectively, while the mean depth of the RG ranged from 0.75 to 1.13 mm. Mean canal volume, surface area and SMI were 10.78 mm³, 58.51 mm², and 2.84, respectively. Apical delta was present in 4.35% of the sample and accessory canals were observed more frequently at the middle and apical thirds. Two-dimensional parameters indicated an oval-shaped cross-sectional appearance of the root canal at the apical level with a high percentage frequency of canal divisions (87.15%). Canal configurations types V (58.57%), I (12.85%), and III (11.43%) were the most prevalent. C-shaped configuration was observed at the level of the RG in 13 premolars (18.57%), whereas mean dentinal thickness ranged from 1.0 to 131 mm.

Conclusions: The presence of RG in mandibular first premolars was associated with the occurrence of several anatomical complexities, including C-shaped canals and divisions of the main root canal.

Introduction

Unsuccessful root canal treatment is mainly caused by failure to recognize variations in root and canal morphologies. Therefore, a thorough knowledge of the morphology of the teeth and an expectation of their likely variations is paramount to minimize endodontic failure caused by incomplete debridement and obturation (Vertucci 2005). Previous studies have shown different trends in the shape and number of roots and canals among populations (Walker 1987, 1988, Gulabivala et al. 2001, Gulabivala et al. 2002, Sert & Bayirli 2004), which appear to be genetically determined (Trope et al. 1986, Chaparro et al. 1999, Cleghorn et al. 2007) and are important for tracing the racial origins of populations.

The presence of developmental depressions in the proximal aspects of the root surface, also referred as radicular grooves (RG) (Tomes 1923), have been demonstrated in different epidemiological studies. Overall, RG is widespread in Africans and native Australians and relatively rare in Western Eurasians (Trope et al. 1986, Scott & Turner II 2000, Lu et al. 2006, Cleghorn et al. 2007). The RG is relevant in clinics as its depth may act as a reservoir for dental plaque and calculus, increasing the difficulty for the management of periodontal disease (Fan et al. 2008, Gu et al. 2013a, Gu et al. 2013b). In mandibular premolar teeth, its presence has been associated to anatomical complexities of the root canal system, such as canal bifurcation and C-shaped canal configuration (Lu et al. 2006, Awawdeh & Al-Qudah 2008, Cleghorn et al. 2008, Fan et al. 2008, Gu et al. 2013a, Gu et al. 2013b, Liu et al. 2013). These complexities are frequently neglected, and the inability to recognize and adequately treat all root canal system helps to explain the highest failure rate in nonsurgical canal therapy of this group of teeth (11.45%) as previously reported (Ingle et al. 2008).

In spite of root and canal morphologies of the mandibular first premolar teeth have been described is different ethnic groups (Trope et al. 1986, Walker 1988, Chaparro et al. 1999, Sert & Bayirli 2004, Lu et al. 2006, Cleghorn et al. 2007, Awawdeh & Al-Qudah 2008, Velmurugan & Sandhya 2009, Fan et al. 2012, Gu et al. 2013a, Liu et al. 2013), literature lacks detailed data on the relationship between RG and root canal morphology in this group of teeth specially in African, Australasian, South East Asian and South American populations. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the external and internal morphologies of single-rooted mandibular first premolars with radicular grooves from a Brazilian subpopulation, using micro-CT technology.

Materials and methods

Sample selection and image acquisition

After local Research Ethics Committee approval (Protocol 0072.0.138.000-09), five-hundred single-rooted mandibular first premolar teeth from a Brazilian subpopulation were obtained and stored in 0.1% thymol at 6° C. The gender and age of the patients were unknown, and all teeth were extracted from reasons not related to this study.

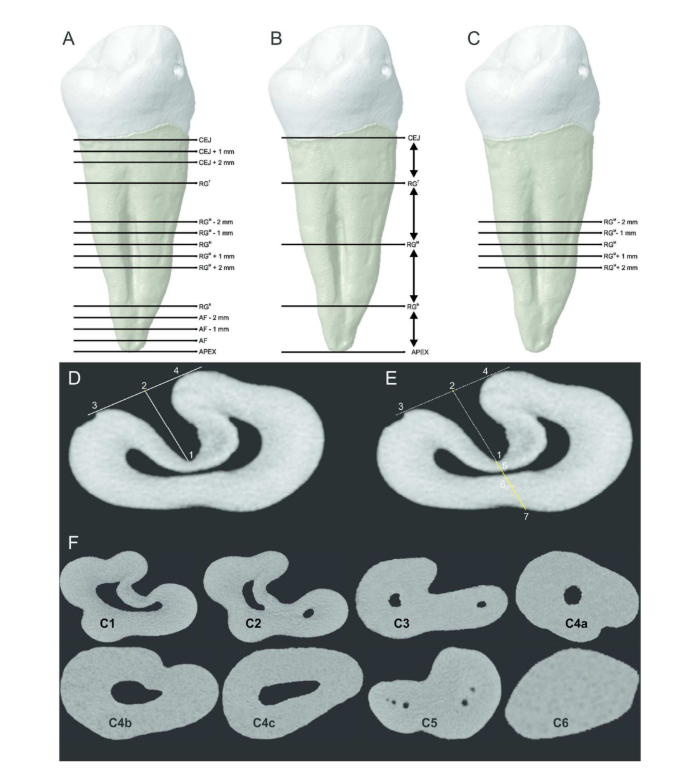

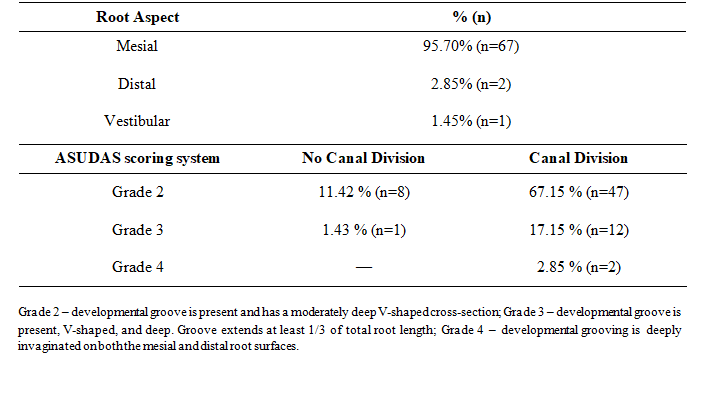

Each tooth was slightly dried and examined regarding the number and percentage frequency location of the developing grooves on the external root surface. Scoring of the prevalence and severity of the radicular grooves (RG) was based on the Arizona State University Dental Anthropology Scoring System (ASUDAS) using a standardized reference plaque (Turner et al. 1991). Teeth categorized as Grades 0 and 1, indicating single-rooted premolars without a development groove or, if present, with a rounded or shallow V-shaped indentations, as well as, Grade 5 (double-rooted premolars), were excluded. As a result, seventy mandibular first premolars (n=70) with fully formed apices were selected and categorized as follows: Grade 2 – developmental groove with a moderately deep V-shaped cross-section; Grade 3 – single root with a deep V-shaped development groove which extends at least 1/3 of the total root length; and Grade 4 – single root having a deeply invaginated development groove on both the mesial and distal root surfaces. In each sample, the root length was measured as the vertical distance between the lowest level of the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) and the anatomic apex (Figure 1A), by using a digital caliper with a resolution of 0.01 mm (Mitutoyo MTI Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Each specimen was then imaged separately from the anatomic apex to the crown at an isotropic resolution of 22.9 µm (SkyScan 1174v2; Bruker-microCT, Kontich, Belgium). The micro-CT scanner parameters were set at 50 kV, 800 µA, 180° rotation around the vertical axis, and rotation step of 1°, using a 0.5-mm-thick aluminum filter. After the acquired projection images were reconstructed into cross-section slices perpendicular to the long axis of the root (NRecon v.1.6.9 software; Bruker-microCT), polygonal surface representations of the root canals were rendered (CTAn v.1.16 software; Bruker-microCT) and surface modeling (CTVol v.2.3 software; Bruker-microCT).

Each tooth was then resliced perpendicularly at the CEJ plane, at the anatomic apex, at the apical foramen, at the top, middle and bottom levels of the RG, and at 1- and 2-mm intervals coronally and/or apically to the CEJ, apical foramen and middle level of the RG, using ImageJ v.1.6.0_24 software (available at www.imagej.nih.gov/ij/) (Figure 1A). After that, the distances between the CEJ plane, the anatomic apex and the top, middle, and bottom levels of the RG were recorded (Data Viewer v.1.5 software; Bruker-microCT) (Figure 1B).

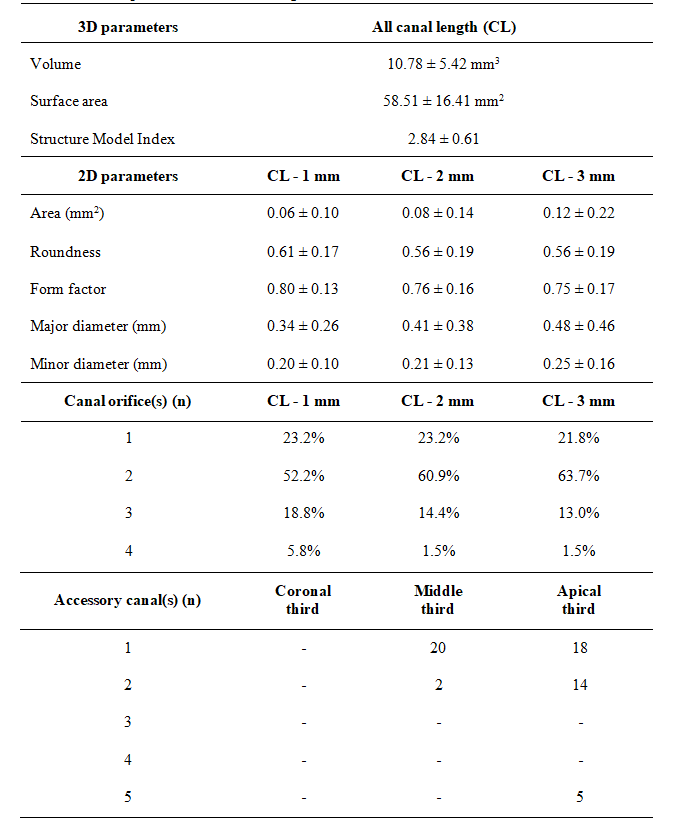

Three-dimensional parameters (volume, surface area and Structure Model Index) were measured for the full canal length, while area, roundness, form factor, major and minor diameters, as well as, the percentage frequency of canal orifices, were evaluated at 1, 2, and 3 mm levels from the apical foramen in a coronal direction (CTAn v.1.14.4 software; Bruker-microCT). Detailed descriptions of these parameters were published elsewhere (Peters et al. 2000, Versiani et al. 2013). The number and location of accessory canals (lateral canals and apical delta) were also recorded. Based on the reconstructed cross-section slices and polygonal 3D models, the configurations of the root canals were classified according to Vertucci’s system (Vertucci 2005).

The depth of the developmental groove and the dentinal thickness at the deepest point of the RG were measured at the middle level of the RG length (RGM) and at 1- and 2-mm intervals coronally and apically to this point (CTAn v.1.16 software; Bruker-microCT) (Figure 1C). The depth of the RG was defined as the distance from the deepest point of the groove to the midpoint between the 2 points of tangency at the contour line of the groove (Figure 1D). For the measurement of the internal and external dentinal thickness, the line traced to measure the groove depth was extended from the deepest point of the groove through the external surface on the other aspect of the root. Then, the distances from the deepest point of the groove to the inner root canal wall, and from the outer root canal wall to the external aspect of the root, were recorded as internal and external dentinal thickness, respectively (Figure 1E).

Cross-sectional canal shapes of the mandibular first premolars were categorized according to a modified system (Fan et al. 2008) (Figure 1F) at the level of the CEJ, apical foramen, middle level of the RG length, as well as, at 1- and 2-mm intervals in the coronal and/or apical directions from these landmarks (Figure 1A). Then, the number of teeth with C-shaped canals at least in one of the evaluated levels was recorded.

All images were independently and blindly examined on a high-definition computer screen by two experienced and pre-calibrated evaluators. Disagreement in the interpretation of the images was discussed until a consensus was reached.

Results

The incidence of single-rooted mandibular first premolars with developmental grooves grades 2 to 4 was 14% (70 out of 500 premolar teeth).

External morphology of the root

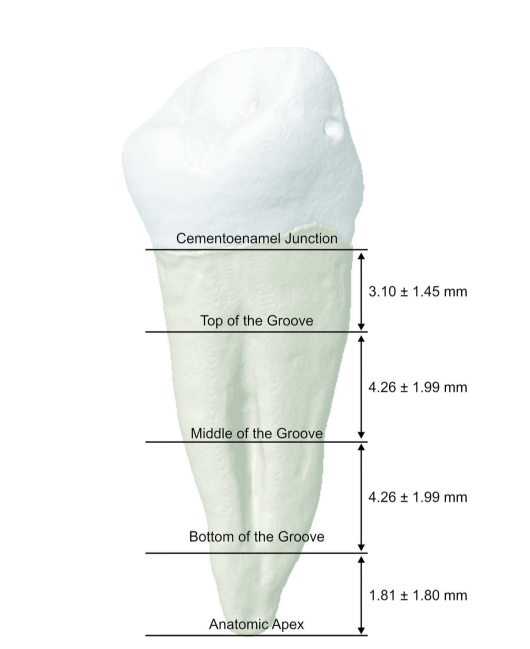

Mean root length was 13.43 ± 1.42 mm, while the mean distances between the CEJ and the middle level of the RG, and from this point to the anatomical apex, were 7.36 mm and 6.07 mm, respectively (Figure 2). Radicular grooves were present mostly in the mesial aspect of the root (Table 1; Figure 3A) and expression of deep grooves (ASU 3 and 4) was observed in 25.71% of the sample (n=18) (Table 1). A high percentage frequency of canal divisions was observed (87.15%; n=61) and, in these teeth, the lingual canal after bifurcation was smaller in diameter when compared with the buccal canal (Figure 3B).

Morphology of the root canal system

Table 2 summarizes morphometric data (2D and 3D parameters) and the percentage number of canal orifices and accessory canals in different levels of the root. Mean volume and surface area were 10.78 mm3 and 58.51 mm2, respectively. The Structure Model Index (SMI) describes the three-dimensional convexity of the structure (Hildebrand & Rüegsegger 1997), i.e. the plate- or cylinder-like geometry of an object. In this study, a mean SMI of 2.84 indicates that the root canal system had a conical frustum-like geometry. Analysis of the area, roundness, and form factor indicated an oval-shaped cross-sectional appearance of the root canal in the apical third. At this same level, the mean major and minor diameters showed an anatomical dimension of the root canal equivalent to a size 35, taper .06 instrument.

At the apical third, a high percentage frequency of 2 canal orifices (> 52%) was observed, while apical delta was present in only 4.35% of the sample (Figure 3C). Overall, one or two accessory canals were observed in the middle and apical thirds; however, accessory canals originated from the main canal and exiting at the radicular groove was also observed in 15.9% of the sample (n=11) (Figure 3D). Canal configurations types V (1-2 configuration; 58.57%), I (1-1 configuration; 12.85%), and III (1-2-1 configuration; 11.43%) were the most prevalent and additional canal configurations (Types 1-3 and 1-2-3) were also observed. In two teeth, the canal system could not be classified because of the presence of unanticipated multifurcations and a C-shaped canal at the middle third of the root (Figure 3E). Overall, C-shaped configuration (Types C1 and C2) was observed at the level of the RG in 13 premolars (18.57%). At the level of the CEJ, teeth usually had only 1 round, oval or flat canal orifice (Types C4a, 4b and 4c), while in the apical third, the majority of the canal shapes were Types C3 and C5.

Dentinal thickness

RG depth varied from 0.75 to 1.13 mm and was deeper in the cross-section corresponding to the middle point of its full length. The mean dentinal thickness at the middle level of the RG length in either mesial or distal aspects of the root ranged from 1.0 to 1.31 mm (Table 3).

Discussion

Successful endodontic treatment of mandibular premolars has been considered difficult to perform because of the numerous variations in root canal morphology usually associated with the presence of developmental root concavities (Cleghorn et al. 2007, Cleghorn et al. 2008, Fan et al. 2012). In the present study, the incidence of RG in mandibular first premolars (14%) was similar to that reported by Velmurugan & Sandhya (2009), but lower in comparison to the Chinese population (24% to 27.8%) (Fan et al. 2008, Liu et al. 2013). This discrepancy has been mostly attributed to racial factors, but also to diversities in sample size, study design, and evaluation method (Cleghorn et al. 2007). While a common standard has been used for identification of RG, herein, premolar teeth were selected based on the ASUDAS (Scott & Turner II 2000), a common standardized tool used in anthropology that allows to set more precisely a threshold between a slight root depression and a typical groove, overcoming the lack of accuracy in sample selection that may have compromised some previous studies. Using this approach, a recent study in the Chinese population found a higher percentage frequency of deep RG (18.5%; ASU 3 to 5) (Gu et al. 2013a) than the present results (14%). Although it has been observed variations regarding the point of initiation and depth of RG in mandibular first premolar (Fan et al. 2008, Liu et al. 2013), its mean length (8.6 mm; Figure 2) and location (95.7% at the mesial aspect of the root; Table 1) are in accordance to the literature (Woelfel & Scheid 2002, Fan et al. 2008, Gu et al. 2013a, Gu et al. 2013b).

The analysis of the morphological features of the root canal system is critical in order to establish adequate treatment protocols. In this way, micro-CT algorithms allow further measurements of several geometric parameters (Peters et al. 2000, Versiani et al. 2013), most of them impossible to achieve using conventional methods. Unfortunately, volume, surface area and SMI results (Table 2) cannot be compared to the literature because no information on this subject was published to date. Despite the clinical relevance of these parameters is still to be determined, they are useful to improve sample selection in further ex vivo experiments (Versiani et al. 2013). In this study, mean thickness of the dentine at the middle level of the RG varied from 1.0 to 1.31 mm (Table 3); however, values as low as 0.12 mm were also observed, in accordance with Gu et al. (2013b) which have reported thickness of 0.17 mm in the mesial walls of the developing grooves. Therefore, in this group of teeth, it has been recommended a conservative shaping preparation with small instruments and adequate irrigation to effectively remove tissues from this narrowed space, preventing strip perforation (Fan et al. 2012).

Evaluation of 2D parameters at the apical third indicated that the debridement at this level could be improved with instruments up to a size 35, taper .06 (Table 2). However, the cross-sectional appearance of the root canal (roundness and form factor) indicates an oval shape which, combined with multiples orifices, accessory canals, apical delta and a high incidence of C-shaped configuration (Tables 2 and 4; Figure 3), could compromise adequate cleaning and shaping procedures (Lu et al. 2006, Awawdeh & Al-Qudah 2008, Gu et al. 2013a, Liu et al. 2013). Accessory canals were observed in nearly half of the sample (45.7%; n=32), as also reported by Gu et al. (2013a). Among these teeth, 37.5% (n=12) had transverse accessory canals exiting at the deepest invagination of the developmental groove (Figure 3D). This finding is relevant in clinics because this anatomical structure may allow penetration of bacteria from periodontal pocket into the pulp and vice versa, leading to a pulpitis or persisting periodontitis (Cleghorn et al. 2008, Gu et al. 2013a). If these anatomic features lead to treatment failure and surgery becomes necessary, these additional structures need to be addressed. Therefore, surgical operative microscope would help clinicians to better visualize the apex (Lu et al. 2006, Gu et al. 2013a) and thin ultrasonic tips to incorporate the anatomical irregularities, ensuring a proper canal sealing.

Although most of the mandibular premolars have one main root canal, when RG is present, multiple canals with more complex configuration can be observed (Cleghorn et al. 2007, Cleghorn et al. 2008). Unfortunately, only a few authors have described the root canal configuration system of mandibular premolar teeth with RG (Fan et al. 2012, Gu et al. 2013a, Liu et al. 2013). In these studies, a high incidence of canals types V (26.4% to 65.6%) and I (6.3% to 15%) have been reported, in accordance with the present results. On the other hand, type III configuration was also identified in a relatively high percentage of mandibular first premolars (11.43%) (Figure 3E).

The main anatomic feature of C-shaped canals is the presence of fins or webs connecting individual canals which may change the cross-sectional and three-dimensional canal shape along the root (Fan et al. 2008). Current knowledge derived from micro-CT studies indicated that this ribbon canal space in mandibular first premolars is frequently eccentric to the lingual side of the C-shaped radicular dentin, and that C-shaped canal varies considerably in shape at different levels (Cleghorn et al. 2008, Fan et al. 2008, Fan et al. 2012, Li et al. 2012, Gu et al. 2013a, Gu et al. 2013b, Liu et al. 2013). In this study, the percentage frequency of C-shaped canals was high (18.57%), but within the range of 10.7% to 29% reported in the literature (Baisden et al. 1992, Sikri & Sikri 1994, Lu et al. 2006, Cleghorn et al. 2007, Awawdeh & Al-Qudah 2008, Fan et al. 2008, Fan et al. 2012, Gu et al. 2013b). However, in disagreement with a previous study in which a continuous C-shaped canal was observed in more than 16% of the sample (Fan et al. 2012), in this study no specimen was found to contain a complete C over the root length.

Many complicating factors make C-shaped canals in mandibular premolars difficult to treat (Lu et al. 2006) because this configuration is rarely seen in the radiography (Gu et al. 2013a) and its location may hamper its detection from a coronal approach (Lu et al. 2006, Gu et al. 2013a). All evaluated teeth in this study had only 1 canal orifice at the coronal level (Type C4), while C-shaped canal configuration (Types C1 and C2) was observed at the middle third, in agreement with previous reports (Gu et al. 2013a, Gu et al. 2013b). Therefore, considering that this anatomical variation in mandibular premolars cannot be easily identify during routine endodontic treatment (Gu et al. 2013a) or by conventional radiography (Cleghorn et al. 2008), the effect of its shaping and cleaning on the success rate of the endodontic treatment is still to be determined (Fan et al. 2012).

Despite resolution of the available CBCT devices does not allow for a detailed imaging of fine anatomical structures of the root canal system (Ordinola-Zapata et al. 2017), this diagnostic tool would be of great help for clinicians in order to identify the presence of RG (Liu et al. 2013). Considering that mandibular premolar teeth with an associated groove on the external root surface have a high incidence of C-shaped canals and bifurcations (Lu et al. 2006, Fan et al. 2012, Gu et al. 2013a, Gu et al. 2013b, Liu et al. 2013), previous detection of RG would suggest the presence of the anatomical complexities reported herein. In summary, the mandibular first premolar teeth with RG from a Brazilian subpopulation evaluated in this study were associated with a high occurrence of several anatomical complexities, including C-shaped canals and bifurcation.

Legends

Figure 1. (A) The root was digitally resliced perpendicularly at the cementoenamel junction plane (CEJ), at the anatomic apex (APEX), at the apical foramen (AF), at the top (RGT), middle (RGM) and bottom (RGB) levels of the groove, and at 1- and 2-mm intervals coronally and/or apically to the CEJ, AF and RGM planes; (B) vertical planes measurements between the CEJ plane, the anatomic apex , the top, middle, and bottom levels of the RG were measured; (C) measurement levels of the depth of the developmental groove and the dentinal thickness at the middle of the full RG length and at 1- and 2-mm intervals coronally and apically to this point; (D) The depth of the RG was defined as the distance from the deepest point of the groove (1) to the midpoint (2) between the 2 tangency points (3 and 4) to the contour line of the groove; (E) Measurement of the internal and external dentinal thickness were performed from the deepest point of the groove (1) to the inner root canal wall (5), and from the outer root canal wall (6) to the external aspect of the root (7), respectively; (F) Cross-sectional canal shapes were categorized into 8 types according to a modified system as C1: continuous “C” with no separation or division; C2: canal shape resembled a semicolon resulting from a discontinuation in the “C” outline; C3: 2 separated round, oval, or flat canals; C4: only 1 round, oval, or flat canal in that cross-section (C4a: the long canal diameter almost equal to the short diameter; C4b: the long canal diameter was at least 2 times shorter than the short diameter; C4c: the long canal diameter was at least 2 times longer than the short diameter); C5: 3 or more separate canals in the cross-section; C6: no canal lumen.

Figure 2. Mean distance, in millimeters, between several anatomical landmarks at the external aspect of the root of mandibular first premolar teeth.

Figure 3. 3D models of mandibular premolars showing (A) RG with different depths and lengths in different aspects of the root; (B) accessory canals in the apical and middle thirds of the root; (C) two premolars with apical delta; (D) a premolar with accessory canals originated from the main canal and exiting at the radicular groove; (E) the percentage frequency distribution of different root canal configurations observed in mandibular first premolar teeth.

References:

- Awawdeh LA, Al-Qudah AA (2008) Root form and canal morphology of mandibular premolars in a Jordanian population. International Endodontic Journal 41, 240-8.

- Baisden MK, Kulild JC, Weller RN (1992) Root canal configuration of the mandibular first premolar. Journal of Endodontics 18, 505-8.

- Chaparro AJ, Segura JJ, Guerrero E, Jimenez-Rubio A, Murillo C, Feito JJ (1999) Number of roots and canals in maxillary first premolars: study of an Andalusian population. Endodontics and Dental Traumatology 15, 65-7.

- Cleghorn B, Christie W, Dong C (2007) The root and root canal morphology of the human mandibular first premolar: a literature review. Journal of Endodontics 33, 509-16.

- Cleghorn BM, Christie WH, Dong CC (2008) Anomalous mandibular premolars: a mandibular first premolar with three roots and a mandibular second premolar with a C-shaped canal system. International Endodontic Journal 41, 1005-14.

- Fan B, Yang J, Gutmann JL, Fan M (2008) Root canal systems in mandibular first premolars with C-shaped root configurations. Part I: Microcomputed tomography mapping of the radicular groove and associated root canal cross-sections. Journal of Endodontics 34, 1337-41.

- Fan B, Ye B, Xie E, Wu H, Gutmann J (2012) Three-dimensional morphological analysis of C-shaped canals in mandibular first premolars in a Chinese population. International Endodontic Journal 45, 1035-41.

- Gu Y, Zhang Y, Liao Z (2013a) Root and canal morphology of mandibular first premolars with radicular grooves. Archives of Oral Biology 58, 1609-17.

- Gu YC, Zhang YP, Liao ZG, Fei XD (2013b) A micro-computed tomographic analysis of wall thickness of C-shaped canals in mandibular first premolars. Journal of Endodontics 39, 973-6.

- Gulabivala K, Aung TH, Alavi A, Ng YL (2001) Root and canal morphology of Burmese mandibular molars. International Endodontic Journal 34, 359-70.

- Gulabivala K, Opasanon A, Ng YL, Alavi A (2002) Root and canal morphology of Thai mandibular molars. International Endodontic Journal 35, 56-62.

- Hildebrand T, Rüegsegger P (1997) Quantification of bone micro architecture with the structure model index. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering 1, 15-23.

- Ingle JI, Bakland LK, Baumgartner G (2008) Endodontics, 6th edn. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc.

- Li X, Liu N, Ye L, Nie X, Zhou X, Wen X, Liu R, Liu L, Deng M (2012) A micro-computed tomography study of the location and curvature of the lingual canal in the mandibular first premolar with two canals originating from a single canal. Journal of Endodontics 38, 309-12.

- Liu N, Li X, Liu N, Ye L, An J, Nie X, Liu L, Deng M (2013) A micro-computed tomography study of the root canal morphology of the mandibular first premolar in a population from southwest China. Clinics of Oral Investigative 19, 999-1007.

- Lu TY, Yang SF, Pai SF (2006) Complicated root canal morphology of mandibular first premolar in a Chinese population using the cross section method. Journal of Endodontics 32, 932-6.

- Ordinola-Zapata R, Bramante CM, Versiani MA, Moldauer BI, Topham G, Gutmann JL, Nunez A, Duarte MA, Abella F (2017) Comparative accuracy of the Clearing Technique, CBCT and Micro-CT methods in studying the mesial root canal configuration of mandibular first molars. International Endodontic Journal 50, 90-6.

- Peters OA, Laib A, Ruegsegger P, Barbakow F (2000) Three-dimensional analysis of root canal geometry by high-resolution computed tomography. Journal of Dental Research 79, 1405-9.

- Scott GR, Turner II CG (2000) The anthropology of modern human teeth: Classification., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sert S, Bayirli GS (2004) Evaluation of the root canal configurations of the mandibular and maxillary permanent teeth by gender in the Turkish population. Journal of Endodontics 30, 391-8.

- Sikri VK, Sikri P (1994) Mandibular premolars: aberrations in pulp space morphology. Indian Journal of Dental Research 5, 9-14.

- Tomes CS (1923) A manual of dental anatomy: human and comparative, 8 edn. New York.: MacMillan Co.

- Trope M, Elfenbein L, Tronstad L (1986) Mandibular premolars with more than one root canal in different race groups. Journal of Endodontics 12, 343-5.

- Turner CGII, Nichol CR, Scott GR (1991). Scoring procedures for key morphological Traits of the permanent dentition: The Arizona State University dental anthropology system. In: Kelley MA and Larson CS, eds. Advances in Dental Anthropology, pp. 13-31. New York: Wiley-Liss.

- Velmurugan N, Sandhya R (2009) Root canal morphology of mandibular first premolars in an Indian population: a laboratory study. International Endodontic Journal 42, 54-8.

- Versiani MA, Pécora JD, Sousa-Neto MD (2013) Microcomputed tomography analysis of the root canal morphology of single-rooted mandibular canines. International Endodontic Journal 46, 800-7.

- Vertucci FJ (2005) Root canal morphology and its relationship to endodontic procedures. Endodontic Topics 10, 3-29.

- Walker RT (1987) Root form and canal anatomy of maxillary first premolars in a southern Chinese population. Endodontics and Dental Traumatology 3, 130-4.

- Walker RT (1988) Root canal anatomy of mandibular first premolars in a southern Chinese population. Endodontics and Dental Traumatology 4, 226-8.

- Woelfel JB, Scheid RC (2002) Dental anatomy: its relevance to dentistry, 6th edn. Philadelphia.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.