Non-Carious Lesions: Tooth Wear. Excessive Attrition, Abrasion, Erosion

In literature and classifications, both specific and broad terms are used to describe the posteruptive loss of tooth structure in the form of tooth wear.. Specific terms such as attrition, abrasion, erosion, and abfraction pinpoint distinct causes of tissue loss, while broader terms like tooth wear and tooth surface loss encompass multiple factors.

In the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) posteruptive non-carious lesions are categorized into:

- K03 Other diseases of hard tissues of teeth

- K03.0 Excessive attrition of teeth

- K03.1 Abrasion of teeth

- K03.2 Erosion of teeth

- K03.4 Hypercementosis

- K03.7 Posteruptive colour changes of dental hard tissues

- K03.8 Other specified diseases of hard tissues of teeth

- K03.9 Disease of hard tissues of teeth, unspecified

Specific terms offer clarity regarding the etiology of tissue loss. However, defects often arise from a combination of factors, with one initiating the condition and another contributing to its progression. Additionally, similar causative factors can result in lesions in varying locations, further complicating diagnosis.

- Attrition refers to the loss of hard tooth tissue due to contact between opposing teeth, typically affecting the occlusal surfaces.

- Abrasion describes the wear of tooth structures or restorations caused by external mechanical forces, such as vigorous brushing, abrasive toothpaste, or habits like chewing seeds. This type of wear commonly appears on cervical and occlusal surfaces.

- Erosion denotes the loss of tooth tissue caused by acid-induced demineralization, often localized on vestibular cervical surfaces or occlusal and oral surfaces, depending on the acid's origin.

Understanding the connection between bruxism, non-carious lesions (excessive attrition, abrasion, and erosion), and temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) is essential for providing comprehensive patient care. Our “Online Congress on Evidence-Based Temporomandibular Disorders and Bruxism Treatment” is designed to equip you with the knowledge and protocols to manage these interrelated conditions effectively. In this course, you'll explore the interconnection between bruxism and pathological tooth wear, diving into topics such as:

- Clinical signs of bruxism and its role in tooth wear.

- Causes of tooth wear, including mechanical attrition, chemical erosion, and abrasion.

- Functional wear prevention and treatment strategies for bruxism patients.

- Diagnosing and managing TMDs with evidence-based principles.

This congress is essential for dentists aiming to diagnose, prevent, and treat these conditions using evidence-based protocols.

Excessive Attrition of Teeth

Excessive attrition of teeth is the progressive loss of hard dental tissues due to tooth-to-tooth contact, exceeding the physiological wear process. This pathological wear can impair chewing function and lead to various complications, it can be found on occlusal or proximal surfaces.

It is important to differentiate pathological attrition from physiological attrition, which occurs naturally due to the normal function of opposing or adjacent teeth during chewing and swallowing. Physiological tooth wear serves an adaptive purpose, acting as a safeguard against the functional overloading of teeth. It is a slow, compensated process that enhances chewing efficiency, facilitates smooth mandibular movements, and ensures seamless occlusal contact during various phases of articulation. This natural phenomenon involves the gradual loss of occlusal surfaces within the enamel's limits.

Etiology

Excessive attrition can result from:

- Malocclusion and bite irregularities

- Overloading due to tooth loss

- Occupational or habitual factors

- Dietary habits and the abrasiveness of food

- Biophysical properties of saliva (e.g., hyposalivation or xerostomia)

- Poor dental treatments or dentures

Experimental studies confirm a link between attrition and food abrasiveness, as well as the progression of wear in cases of reduced salivary flow.

Epidemiology

Attrition prevalence increases with age and is more pronounced in individuals with dietary or professional exposure to abrasive materials. Although rare in children and adolescents, its incidence has increased in these groups in recent years. In developed countries, longer life expectancies have contributed to rising rates of pathological wear among older populations.

Pathogenesis and Pathological Anatomy

The pathogenesis of increased tooth wear involves a complex interplay of factors. These include heightened occlusal load, exogenous influences such as occupational hazards, dietary habits, and improper prosthetic designs that fail to consider the friction coefficient and surface roughness of the materials. Additionally, endogenous factors like metabolic disorders, endocrinopathies, bruxism, and gastrointestinal diseases contribute to the process. The lack of effective repair mechanisms exacerbates tissue damage, leading to sensitivity, malocclusion, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) changes.

The loss of hard dental tissues triggers protective mechanisms, including mineral deposition within dentinal tubules, surface mineralization of exposed dentin, and formation of reparative dentin. These changes enhance resistance to demineralization but may contribute to dentin hypersensitivity in some cases. When reparative dentin formation lags behind tissue loss, pulp infection, necrosis, and apical bone destruction can occur.

Enamel: Shows elongated hydroxyapatite crystals with reduced clarity and tightly packed inter-prismatic spaces.

Dentin: Increased microhardness with obliterated tubules, surrounded by hypermineralized intertubular dentin.

Pulp: Early stages show disorganized odontoblasts, nuclear pyknosis, and vascular sclerosis. Advanced cases may lead to pulp fibrosis or calcification.

Clinical Presentation

- Uneven wear, particularly in trauma-prone areas.

- Sharp edges causing soft tissue injuries.

- Flattened or misshapen teeth.

- Sensitivity due to dentin exposure.

- Changes in facial height in advanced cases, along with oral mucosal changes, hearing impairment, and TMJ discomfort.

Worn teeth are notably resilient and show no clinical signs of periodontal disease. This can be attributed to the reduction of the lever arm caused by the shortening of the supragingival portion of the tooth. Radiographic studies usually reveal a normal periodontal structure, with no evidence of bone resorption in the sockets of worn teeth. The periodontal ligament space remains unchanged in most cases. However, under conditions that promote functional overload (such as bruxism, significant tooth loss, or malocclusion), bone destruction and widening of the periodontal ligament space can occur.

The various forms and degrees of occlusal curve expression often reflect the unique characteristics of mandibular movements in individual patients. A significant clinical feature of pathological tooth wear is enamel and dentin hypersensitivity, although not all patients experience it. This sensitivity may affect one, several, or all teeth. Generalized pathological wear is often accompanied by a reduction in occlusal vertical dimension and the lower third of the face's height. The extent of these changes depends on the depth of hard tissue wear and the type of occlusion, and in cases of dental arch defects, on their size and location.

Decreased occlusal vertical dimension and facial height often coincide with masticatory muscle parafunction (bruxism) and mandibular displacement. This alters the topographical relationships within the TMJ. The complexity of such cases can obscure causative links between components of the pathological chain (excessive attrition, periodontal involvement, bruxism, and TMJ dysfunction).

Classification

Horizontal attrition: Tissue loss in a horizontal plane (most common).

Vertical attrition: Proximal surface loss.

Mixed attrition: Combined horizontal and vertical wear.

Severity levels:

Grade I: Enamel wear without dentin exposure.

Grade II: Complete cusp or edge wear within dentin.

Grade III: Tooth wear reaching the pulp chamber, with secondary dentin formation.

Treatment

Comprehensive management considers the underlying causes:

Mild cases: Dietary adjustments and bite realignment.

Severe cases: Restorative procedures (e.g., fillings or crowns) and prosthetic rehabilitation.

Physiological and mild pathological attrition without bruxism generally does not require treatment. Early diagnosis, prevention of causative factors, and therapeutic or prosthetic intervention are essential for managing wear that affects bite height or progresses significantly.

Restoration of non-carious defects in such teeth is challenging due to the altered morphology of dentin. Hypermineralized layers often hinder adhesive penetration, reducing bond strength.

The choice of restorative materials is critical, and treatment focuses on stabilizing wear and preventing further progression. Early stages can often be managed with preventive measures, fluoride therapies, and selective grinding. Moderate wear may require direct restorations or prosthetics to restore tooth anatomy and function. For extensive tooth loss, prosthetics or implants are recommended to restore the dental arch.

Prosthetic treatment improves chewing, aesthetics, and joint health while preventing further wear. Preventive measures, such as avoiding abrasives, using protective equipment, and regular dental check-ups, are cost-effective. Timely intervention for chips or caries and tailored oral hygiene are vital.

In cases of excessive attrition, where mechanical forces like bruxism or grinding have caused significant loss of tooth structure, the Index Technique offers a solution that prioritizes preservation, function, and aesthetics. By creating a wax-up or digital model, this technique allows dentists to precisely restore the lost occlusal height, ensuring proper function and bite stability.

Do you want to gain insights into cost-effective and patient-friendly solutions for pathological tooth wear that are already revolutionizing dental practices worldwide? Join our course “The Index Technique No-Prep Worn Dentition Treatment” now to learn how to implement this cutting-edge technique and elevate your restorative dentistry skills! This course, led by Dr. Riccardo Ammannato, the pioneer of the Index Technique, provides step-by-step guidance on diagnostics, wax-ups for VDO adjustments, and practical restoration protocols.

Prevention

- Identifying and addressing malocclusion.

- Dietary counseling.

- Use of protective appliances for bruxism.

Abrasion of Teeth

Abrasion is the progressive loss of hard dental tissues caused by mechanical actions, such as brushing or contact with objects and substances (synonyms: wedge-shaped defect, abrasive wear).

ICD Codes:

K03.10 Abrasion from toothpaste/powder (wedge-shaped defect).

K03.11 Due to habits.

K03.12 Occupational.

K03.13 Traditional ritualistic.

K03.18 Other specified abrasion.

K03.19 Unspecified abrasion.

Etiology

Abrasion arises from poor brushing techniques (too much pressure or high frequency), abrasive toothpaste, and hard-bristled brushes. It may also result from harmful habits (e.g., smoking pipes, chewing pens, using teeth as tools like holding needles for sewing), occupational tools or environments (for example, working in cement or granite factory), or cultural practices like betel nut chewing, cleaning teeth with twigs or charcoal.

Epidemiology

The prevalence varies from 5% to 85% and increases with age.

Pathogenesis and Pathological Anatomy

Abrasion predominantly affects the cervical region, forming V-shaped defects. It involves mechanical wear exacerbated by chemical factors, leading to progressive enamel and dentin loss.

Affected enamel shows increased density and mineralization, with obliterated dentin tubules. In advanced cases, atrophic changes occur in the pulp.

Clinical Features

Abrasion often presents as smooth, shiny notches near the cemento-enamel junction, resistant to staining. They can be either flat, shallow, dish-shaped, or deep and wedge-shaped. Advanced stages may expose dentin, leading to hypersensitivity and potential pulp involvement.

Treatment

Identifying risk factors is crucial for managing abrasion. This involves analyzing oral hygiene habits, including brushing technique, frequency, and choice of toothpaste or powders, as some can be highly abrasive. The location of abrasion defects helps pinpoint causes. For dentine sensitivity, desensitizing toothpaste or resin can be used, with careful surface preparation and adherence to product guidelines.

Non-carious cervical lesions are often restored with materials like glass-ionomers, composites, or hybrids. Glass-ionomers release fluoride and are adhesive but lack durability, while composites offer better aesthetics and wear resistance, making them ideal for anterior lesions. Resin-modified glass-ionomers improve handling and resistance.

Prevention

Preventive strategies include education on correct brushing methods, use of non-abrasive products, and addressing harmful habits. For occupational risks, protective measures are essential.

Erosion

Erosion is a progressive loss of enamel and dentin caused by their dissolution due to acids and mechanical removal of softened tissues.

Etiology

The primary cause of erosion is prolonged exposure to acids, including acidic foods, citrus fruits, fruit juices, medications with low pH, stomach acid during reflux (gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)), and acid vapors in industrial settings. Disorders like bulimia and anorexia involve frequent vomiting or restrictive eating patterns, increasing the risk of enamel erosion. Specific professions, such as winemakers, sommeliers, swimmers, and workers in chemical industries, face higher risks due to frequent exposure to acidic environments. Decreased saliva flow and buffering capacity contribute to an inability to neutralize acids and remineralize enamel effectively. Cases of enamel erosion of unclear origin are also observed.

Epidemiology

The prevalence ranges from 20% to 45% in children and adolescents and up to 80% in adults, with higher rates observed in industrialized nations due to increased consumption of acidic foods and beverages.

Pathogenesis and Pathological Anatomy

Polarized light microscopy and tooth grinding techniques reveal that the initial stage of enamel erosion is surface demineralization. The underlying enamel, dentin, and pulp remain unchanged. As the condition progresses, dentin sclerosis occurs, and pulp changes characteristic of chemical irritation to odontoblasts appear.

Clinical Features

Enamel demineralization is typically found between the tooth’s equator and cervical region. These areas rapidly wear down, forming shallow, cup-shaped defects. Enamel and dentin erosion are classified based on their speed and severity, and can stabilize over time. The disease can be chronic, persisting for decades. In the early stages, the color of the eroded surface matches the natural shade of the tooth, gradually turning yellow or light brown. This is often accompanied by hypersensitivity of the dentin, leading patients to stop brushing. The upper incisors are most commonly affected, with less frequent involvement of canines and premolars. Lower incisors and molars rarely exhibit erosion. Erosion typically affects at least two symmetrical teeth.

Around 80% of patients with erosion report hypersensitivity to various stimuli. Enamel erosion often coexists with other dental issues, such as cavities, wedge-shaped defects, and more. Enamel erosion is classified as initial (affecting only enamel) or advanced (involving dentin). In initial erosion, the tooth surface appears shiny but becomes matte when dried.

Advanced erosion leads to defects in the dentin, with the base of the defect appearing yellowish, sometimes darkening to brown.

Many patients mistakenly intensify the problem by using hard toothbrushes and abrasive powders to clean their teeth, or by treating their teeth with lemon juice to whiten them, further exacerbating the erosion. Once the enamel surface is worn away, the underlying dentin, which is softer and more vulnerable, erodes much more quickly. This results in deepening, cup-shaped defects that can eventually lead to complete destruction of the tooth crown.

Erosion has two stages: Active and Stable. In the active stage, the tissue loss is rapid, often accompanied by hypersensitivity. The tooth surface appears matte after drying, with a faint, difficult-to-remove layer that can be scraped with an excavator. In the stable stage, the erosion process slows, and the tooth surface remains free of plaque, shiny after drying, and the tooth is not sensitive.

Treatment

The primary goal is to eliminate the etiological factors. Brushing should not be discontinued, as this can worsen the condition. Stabilizing the process involves remineralization therapy using calcium and fluoride solutions applied several times. Aesthetic restoration is the method of choice. Patients with erosion should be advised to brush with a soft toothbrush and use toothpaste containing calcium and fluoride. Toothpastes with low abrasiveness are essential, and consumption of acidic fruits, juices, and sodas should be minimized. Drinking straws and rinsing the mouth with water can help protect the teeth.

An effective treatment approach involves combined applications of calcium gluconate (10%) and sodium fluoride (2%) solutions.

For advanced erosion (greater than 3mm), aesthetic fillings or crowns may be necessary. However, if the harmful factors persist, the erosion may progress around the fillings.

Prevention

It’s essential to avoid exposure to harmful factors. As consumption of fruit juices and soft drinks has increased, public education on the risks associated with organic acids in these drinks is critical. It’s advisable to limit acidic drinks, use straws, and dilute juices with water.

After consuming acidic drinks, the mouth should be rinsed with water. Toothpaste with fluoride is helpful in remineralization, and brushing immediately after acidic drink consumption should be avoided.

Educating patients on reducing the frequency and quantity of acidic beverages, especially in the evening, and using fluoride-rich, low-abrasion toothpaste (RDA index: 30–50) and soft-bristled brushes is crucial in preventing tooth erosion and hypersensitivity. Patients should be advised to avoid brushing immediately after acidic exposure or vomiting.

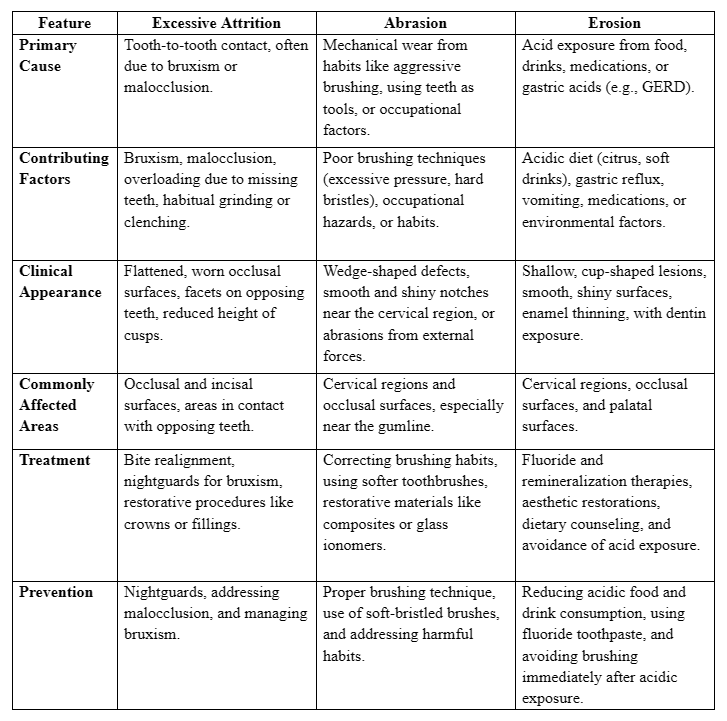

Key comparison table

And all in all, how to treat tooth wear?

Often, it requires an interdisciplinary approach, combining bruxism management, occlusal splint therapy, and aesthetic restoration. Want to master these techniques? Join our course “Worn Dentition Treatment 2.0: Updated And New Protocols”. Learn how to approach this common yet complex condition with confidence through evidence-based diagnostic techniques and structured treatment protocols. You will discover how to differentiate between physiological and pathological tooth wear, analyze etiological factors, and tailor your approach to each patient. From restorative techniques and material selection to functional rehabilitation and anti-aging dental strategies, this course provides you with a complete toolbox for treating worn dentition.