Non-Carious Lesions. Disorders Of Tooth Development: Dental Fluorosis, Molar Incisor Hypomineralization, Enamel Hypoplasia, Amelogenesis Imperfecta

Tooth decay holds one of the leading positions in prevalence among the global population. Diagnosing carious disease, especially in its early stages and understanding its activity, plays a critical role in planning, monitoring, and assessing the effectiveness of preventive measures. Early carious lesions don’t always progress to full-blown cavities. With proactive therapeutic and preventive care, they can either be halted or even reversed.

Nowadays non-carious lesions are as significant as carious lesions when it comes to maintaining oral health. These lesions, which occur without bacterial involvement, can severely impact the structure, function, and aesthetics of teeth. From hypersensitivity and pain to progressive damage and increased risk for secondary caries, such pathology poses unique challenges that require careful diagnosis and management. Understanding their causes, progression, and impact is essential for providing comprehensive dental care and ensuring long-term oral health and patient well-being.

Non-carious lesions cause hypersensitivity primarily due to the exposure of dentin and its underlying nerve-rich structure. Dentinal tubules that lead directly to the dental pulp, where nerve endings reside. And when dentin is exposed, stimuli (temperature, acids, pressure) can easily travel through the tubules to irritate the nerves. Everything you need to know about dealing with this symptom is in our lesson “Hypersensitivity”: how to prevent it, the causes, favouring factors, what to do, choose the right product, advice for patients.

Non-carious lesions are broadly divided into two groups:

- Lesions occurring during the developmental phase of tooth formation (prior to eruption)

- Lesions developing after tooth eruption

Disorders of tooth development encompass a range of conditions that affect the formation, structure, number, size, and eruption of teeth. These disorders can be genetic, environmental, or multifactorial in origin and occur during various stages of tooth development (initiation, morphogenesis, histodifferentiation, and apposition).

Meanwhile, the rising prevalence of non-carious lesions has prompted continuous improvements in diagnostic, treatment, and prevention methods. Clinical observations in outpatient dental settings indicate a high frequency of erosion and wedge-shaped defects among patients. These conditions are no longer limited to older adults; today, even younger individuals increasingly present with such issues.

Classification of Non-Carious Lesions

In the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) non-carious lesions are categorized into:

K00-K14 Diseases of oral cavity, salivary glands and jaws

- K00 Disorders of tooth development and eruption

- K00.2 Abnormalities of size and form of teeth

- K00.3 Mottled teeth

- Dental fluorosis

- Mottling of enamel

- Nonfluoride enamel opacities

- K00.4 Disturbances in tooth formation

- Aplasia and hypoplasia of cementum

- Dilaceration of tooth

- Enamel hypoplasia (neonatal/postnatal/prenatal)

- Regional odontodysplasia

- Turner tooth

- K00.5 Hereditary disturbances in tooth structure, not elsewhere classified

- Amelogenesis imperfecta

- Dentinogenesis imperfecta

- Odontogenesis imperfecta

- Dentinal dysplasia

- Shell teeth

- K00.8 Other disorders of tooth development

- Colour changes during tooth formation

- Intrinsic staining of teeth NOS

- K00.9 Disorder of tooth development, unspecified

- K03 Other diseases of hard tissues of teeth

- K03.0 Excessive attrition of teeth

- K03.1 Abrasion of teeth

- K03.2 Erosion of teeth

- K03.4 Hypercementosis

- K03.7 Posteruptive colour changes of dental hard tissues

- K03.8 Other specified diseases of hard tissues of teeth

- K03.9 Disease of hard tissues of teeth, unspecified

Challenges in Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of non-carious lesions requires differentiating them from both caries and other non-carious conditions. This involves:

- Comprehensive patient history and detailed clinical examinations.

- Utilizing advanced diagnostic techniques such as staining, thermometry, radiography, and biophysical analyses of saliva.

- Consulting with related specialists (e.g., endocrinologists, geneticists, or general practitioners).

Treatment Approaches

Treatment for non-carious lesions encompasses a range of methods, from esthetic restorations to teeth whitening. Modern therapeutic approaches emphasize:

- Correcting tooth discoloration.

- Restoring lost structure while maintaining minimal invasiveness.

- Employing innovative materials and techniques for superior outcomes.

Dental fluorosis

The term “mottled teeth” aptly describes the clinical manifestations of this condition, which include characteristic specks and discoloration on the enamel.

According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD):

- K00.3 Mottled teeth:

- Dental fluorosis

- Mottling of enamel

- Nonfluoride enamel opacities

Dental fluorosis is a systemic developmental disorder of dental hard tissues caused by excessive fluoride intake during the deciduous and permanent dentition amelogenesis. It presents as varying degrees of enamel mottling and even pitting, typically affecting all teeth in the permanent dentition.

Etiology

It is established that chronic intake of high concentrations of fluoride during tooth development interferes with enamel maturation and the effect is cumulative.

Epidemiology

The primary source of fluoride is drinking water. It is also found in the atmosphere and certain foods, including seafood, lamb, liver, animal fats, and egg yolks. While these foods alone do not cause fluorosis, in regions where water fluoride levels exceed 1 mg/L (1.0 ppm F), they contribute to the overall fluoride load.

Fluorosis prevalence reaches:

- 10–12% in areas where water fluoride levels are 0.8–1 mg/L.

- 20–30% at levels of 1.5 mg/L.

In recent years, fluoride-containing foods and beverages, as well as improper ingestion of fluoride toothpaste or topical fluoride solutions during childhood, have been identified as potential risk factors for fluorosis, especially during critical periods of dental development (from the third month of prenatal development to the child’s eighth year). This prompted the WHO to lower recommended fluoride levels in artificially fluoridated water to:

- 0.5 mg/L (0.5 ppm F) in warmer climates.

- 1 mg/L (1.0 ppm F) in cooler climates.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of fluorosis remains incompletely understood. Enamel development occurs during the histogenesis stage, when ameloblasts produce enamel proteins that bind calcium. Normal enamel formation primarily involves hydroxyapatite crystals (Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂). Excess fluoride ions replace hydroxyl ions due to their similar size and charge, forming fluorapatite. Fluoride also binds to enamel matrix proteins and alters crystal structure, impairing normal enamel maturation. Hypermineralized lines are formed due to the higher fluoride content and such fluorotic bands limit protein resorption and diffusion of mineral ions, thus biomineralization is delayed.

Pathological Anatomy

The most notable morphological changes in fluorosis appear in the superficial enamel layers. Even in mild cases, the enamel’s peripheral areas exhibit discontinuous, chalky bands. Microscopic examination at 200–300x magnification reveals disrupted prism patterns in affected enamel, with a characteristic moiré-like structure. Severe cases may show areas of total enamel disintegration alternating with amorphous structures and irregularly shaped hydroxyapatite crystals.

Clinical Presentation

Fluorosis manifests as symmetrical, stable discolorations on all teeth, with spots or streaks primarily near incisal edges and occlusal surfaces. The enamel is matte, losing its translucency, and appears white, yellow, or brown, with darker centers in more severe cases. Advanced fluorosis can cause pinpoint erosions that may coalesce, creating rough, undermined edges. Despite these changes, dentin sensitivity usually remains within normal limits, and affected areas do not stain with dyes.

Classification

The most commonly used system is Dean’s Classification (1942), but there are others as well. Here’s an overview of the main fluorosis classifications:

Dean’s Index of Dental Fluorosis (1942)

This system categorizes fluorosis into six degrees of severity:

- Normal: Smooth, glossy, pale creamy-white enamel with no visible defects.

- Questionable: Slight changes in enamel translucency, with barely noticeable white flecks or spots.

- Very Mild: Small, opaque white areas on less than 25% of the tooth surface.

- Mild: White opacity covers up to 50% of the enamel surface.

- Moderate: Distinct white opacities on more than 50% of the enamel, often accompanied by slight pitting.

- Severe: Widespread enamel damage, including brown stains, pronounced pitting, and a corroded appearance of the enamel.

TSIF (Tooth Surface Index of Fluorosis)

This system examines the severity of fluorosis based on each tooth surface, ranging from:

- Score 0: Normal enamel.

- Score 1: Small areas of white enamel covering less than one-third of the surface.

- Score 2: Opaque white areas covering at least one-third but less than two-thirds of the surface.

- Score 3: Opaque white areas covering two-thirds or more of the surface.

- Score 4: Brown stains accompanying white areas.

- Score 5: Brown stains and pitting of the enamel.

- Score 6: Loss of the outer enamel surface and brown stains.

- Score 7: Severe loss of enamel with most of the surface affected.

Modified Dean’s Classification

Similar to Dean’s Index but refined to reflect modern diagnostic techniques, emphasizing subtle variations between categories:

0 Enamel is normal and translucent, glossy, and smooth.

1 Enamel is of questionable appearance—neither normal nor warranting a diagnosis of dental fluorosis. There are very slight alterations to the translucency of the enamel, such as opaque white flecks.

2 Very mild dental fluorosis with less than 25% of the tooth enamel affected by small opaque white flecks

3 Mild dental fluorosis with less than 50% of the tooth enamel affected by opaque white areas

4 Moderate dental fluorosis with opaque white areas affecting 50% of the tooth's enamel. There may also be evidence of attrition and dark staining.

5 Severe dental fluorosis involves pitting of the dental enamel surface. All surfaces of the tooth are affected.

Thylstrup and Fejerskov Index (TF Index)

This scale focuses on enamel surface changes visible under close examination:

- TF 0: Normal enamel.

- TF 1-2: Initial opaque white lines at the cusps or along edges.

- TF 3-5: Increasing opacities with potential white patches.

- TF 6-7: Discoloration and pitting.

- TF 8-9: Severe damage with loss of enamel structure.

Treatment

Fluorosis treatment is symptomatic, as tooth development is already complete at the time of diagnosis. Depending on severity, treatment may involve color correction through remineralization therapy, bleaching, enamel microabrasion or infiltration, and aesthetic restorations.

Treatment

Fluorosis treatment is symptomatic, as tooth development is already complete at the time of diagnosis. Depending on severity, treatment may involve color correction through remineralization therapy, bleaching, enamel microabrasion or infiltration, and aesthetic restorations.

How Bleaching is used in Fluorosis Treatment

- Mild Fluorosis: In cases where fluorosis appears as white or faint brown spots, bleaching can help even out the tooth color by lightening the surrounding enamel. This makes the fluorotic spots less noticeable.

- Moderate Fluorosis: For more pronounced discoloration, bleaching may reduce the contrast between the fluorosis stains and the unaffected enamel.

If you’re interested in learning how to achieve and maintain safe and effective bleaching results in your patients? We invite you to the lesson “Tips and Life Hacks of Dental Bleaching for Every Day”. Packed with life hacks, actionable tips, and the latest advancements in dental bleaching, this lesson will empower you to master the art of a dazzling smile!

Prevention

Preventing fluorosis requires limiting fluoride exposure during critical developmental periods. For endemic regions, preventive measures include replacing water sources or defluoridating drinking water. The use of supplemental fluoride (e.g., tablets or mineral water) should only be undertaken under medical supervision. Relocating children from endemic areas during vacations or relying on imported foods may reduce the severity of lesions but is unlikely to prevent them entirely.

Molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH)

Molar Incisor Hypomineralization (MIH) is a developmental dental condition characterized by defective enamel formation, primarily affecting the first permanent molars and incisors. It results in enamel hypomineralization, leading to white, yellow, or brown discolorations, increased sensitivity, and a higher susceptibility to dental decay.

Etiology

The precise etiology of MIH remains elusive, despite extensive clinical and experimental research. Various factors have been proposed, including environmental toxins like dioxins and benzofurans that might affect amelogenesis, particularly during the mineralization and maturation stages. Additionally, frequent respiratory infections during the first three years of life, vitamin D deficiency, the use of antibiotics (especially amoxicillin and macrolides), fetal hypoxia, prolonged breastfeeding, and fever during the third trimester of pregnancy have all been suggested as contributing factors. The possibility of a synergistic effect from multiple factors has been proposed, indicating a multifactorial etiology.

Epidemiology

The first epidemiological study of MIH was conducted in Sweden in 1987, where it was termed "idiopathic hypomineralization of enamel." The prevalence of this condition in children born in 1970 was reported at 15.4%. Today, the global prevalence of MIH ranges from 2.8% to 40.2%. According to experts from the European Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (EAPD), the most suitable age for studying the prevalence of MIH is 8 years, with monitoring in multiple age groups recommended.

Pathogenesis

MIH is characterized by the systemic hypomineralization of enamel, primarily affecting the first permanent molars and incisors. The hypomineralization is due to a disturbance in the function of the ameloblasts which leads to an imbalance in enamel mineralization, resulting in reduced levels of calcium and phosphate, increased carbonate content, and a more porous enamel structure. These changes in enamel structure lead to decreased hardness, increased permeability, and a weakened resistance to mechanical stress, which can cause further dental complications.

Pathological Anatomy

The hallmark feature of MIH is the presence of areas with altered enamel transparency, which often appear as demarcated opacities. These areas can range in color from white, cream, yellow, to brown, and can vary in size from small spots to large areas covering much of the crown. The affected regions are typically located on the occlusal and buccal surfaces of the molars and the vestibular surfaces of the incisors. There is often a clear boundary between the affected and unaffected enamel. The dentin beneath the affected enamel also shows changes, such as the widening of the interglobular dentin zones.

Clinical Presentation

Clinically, MIH can manifest as varying degrees of enamel opacities, sensitivity to thermal and mechanical stimuli, and post-eruptive enamel breakdown due to the weakening of the enamel structure. The condition may also lead to difficulty in maintaining proper oral hygiene, as the affected teeth may be more sensitive to brushing. Esthetic concerns are common, especially when incisors are affected, leading to a significant impact on the patient’s quality of life. The enamel’s poor adhesion to restorative materials also complicates dental treatment.

Classification

MIH can be classified based on the severity of the condition:

- Mild MIH: Characterized by demarcated opacities without post-eruptive enamel destruction, minimal sensitivity, and no significant aesthetic concerns.

- Severe MIH: Features include post-eruptive enamel breakdown, the development of caries, persistent sensitivity, and significant aesthetic problems, leading to a poor quality of life.

Treatment

The treatment of MIH depends on the severity of the condition and the age of the patient. Early diagnosis is crucial to prevent further complications, such as enamel breakdown and caries. Treatment methods include:

- Preventive measures: Early intervention with fluoride varnishes, calcium-phosphate technologies, and fissure sealing can help improve enamel mineralization and prevent further damage.

- Restorative treatment: For more severe cases, restorative treatments such as dental fillings or crowns may be necessary to restore the function and aesthetics of the affected teeth. Composite materials are commonly used, but the poor adhesion of materials to hypomineralized enamel poses challenges.

- Non-invasive treatments: Minimal intervention approaches, such as the use of silver diamine fluoride for hypersensitive teeth, can help manage the condition.

- Extraction: In rare cases where the damage is extensive, extraction of the first permanent molars may be considered.

Prevention

Preventive strategies focus on improving enamel quality during the post-eruptive mineralization phase. Key approaches include:

- Encouraging proper oral hygiene from an early age.

- Using fluoride-containing toothpaste with a concentration of at least 1000 ppm.

- Regular application of fluoride varnishes or gels every two months.

- The use of calcium-phosphate treatments to enhance enamel remineralization.

- Fissure sealing to prevent further damage to hypomineralized molars.

Enamel hypoplasia

According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD):

- K00.4 Disturbances in tooth formation

- Aplasia and hypoplasia of cementum

- Dilaceration of tooth

- Enamel hypoplasia (neonatal/postnatal/prenatal)

- Regional odontodysplasia

- Turner tooth

Enamel hypoplasia is an irreversible disturbance in enamel formation caused either by systemic factors affecting the fetus or child (systemic hypoplasia) or by localized damage to the developing tooth germ during its formation (localized hypoplasia).

The exact etiology is still not completely understood. It is believed that systemic hypoplasia results from disruptions in mineral (primarily calcium-phosphorus) and protein metabolism due to maternal illnesses during pregnancy or diseases affecting the child in early postnatal life. Systemic hypoplasia is more common in premature infants, children with allergies, central nervous system disorders, rickets, or those who have suffered from infectious diseases. Localized hypoplasia may arise from microbial pathogens or mechanical trauma impacting the enamel-forming cells (ameloblasts).

Pathogenesis

One hypothesis suggests that primary alterations begin in ameloblasts during histogenesis, resulting in metabolic disruptions. These impairments affect the secretion of the enamel matrix. Prolonged exposure to harmful factors can cause vacuolar degeneration in ameloblasts, leading to their destruction and halting enamel formation. In severe cases, the same factors may impair odontoblast function, disrupting dentin development.

Pathological Anatomy

Under polarized light, mineralization of enamel appears uneven, with hypoplastic defects often aligning with Retzius lines, whose thickness may vary. The arrangement of enamel prisms becomes irregular; in severe cases, they may curve in spirals or change direction almost perpendicularly. Mineral metabolism disruptions also affect dentin, leading to irregularities in dentinal tubules and an increase in interglobular dentin. To compensate, the pulp produces tertiary dentin, but it shows a reduced number of cellular elements and signs of degeneration.

Clinical Presentation

Enamel hypoplasia manifests as spots, cup-shaped depressions, or linear grooves of varying depth and width that run parallel to the incisal edge or occlusal surface. The spots are clearly demarcated and may range in color from white to yellow or light brown. Lesions typically affect all teeth or a symmetrical group of teeth that develop during the same timeframe.

- Erosions: Found on unchanged enamel, with hard and smooth bases.

- Probing Test: Shows intact, smooth surfaces corresponding to dentin without staining by dyes.

The condition is often asymptomatic, but in severe cases with significant enamel loss, chemical irritants may cause sensitivity. Patients are usually concerned about aesthetic defects rather than functional issues.

The FDI recommends using the Developmental Defect Index for patient evaluation.

Localized hypoplasia can cause crown deformation, as enamel and dentin form abnormally, leading to misshapen teeth or partially/completely absent enamel. This condition frequently affects premolars and is often referred to as Turner’s teeth, named after the researcher who first described it. Such pathology typically results from trauma, localized infection, or radiation exposure affecting a single or limited group of teeth.

Differential Diagnosis

Hypoplasia must be differentiated from other developmental dental disorders, fluorosis, and incipient caries (white spot stage). Local water fluoride levels and patient history play a critical role in making an accurate diagnosis.

Treatment

Mild cases of hypoplasia typically require no treatment. For severe discoloration or structural defects, therapeutic options include microabrasion, restoration, or prosthetics. Whitening techniques are not recommended due to their limited efficacy in such cases.

Prevention

Prevention involves ensuring a healthy lifestyle and timely treatment of primary teeth. Addressing systemic health issues during pregnancy and early childhood is crucial for minimizing the risk of enamel hypoplasia.

Amelogenesis imperfecta (AI)

Amelogenesis Imperfecta (AI) is a hereditary disorder that exclusively affects the development of dental enamel. It results from the presence of genetically mutated genes inherited from a child's parents. The defect leads to enamel maturation disturbances, causing both clinical and morphological abnormalities. These include disorganization of enamel prisms, extremely low crystallization, unevenly arranged hydroxyapatite crystals, and changes in enamel's plasticity, color, and thickness.

Etiology

Amelogenesis Imperfecta is caused by genetic mutations passed down through the parents' reproductive cells. These mutations affect the normal development of enamel, leading to defects in its structure. The condition can be inherited through autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked patterns.

Epidemiology

The population frequency of Amelogenesis Imperfecta internationally ranges from 1 in 700 to 1 in 100,000. This rare condition can affect both men and women, though some studies suggest a higher incidence in women, as the mutation causing the disease is linked to female X chromosomes, which can result in fetal or neonatal mortality in males.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of Amelogenesis Imperfecta involves the failure of proper enamel calcification (insufficient calcification (soft enamel)) and maturation (incomplete removal of the organic matrix (brittle enamel)). There are various mechanisms that cause enamel defects: deficient crystal growth and mineralization or matrix formation, abnormal initiation of the enamel crystallites. Defective enamel formation leads to a reduced ability for enamel to form tightly packed prisms, resulting in weaker and more fragile enamel. Over time, this can lead to tooth discoloration, enamel wear, and in severe cases, tooth loss.

Pathological Anatomy

In areas where enamel is retained, significant changes can be observed, such as irregularity in the enamel prisms, widened inter-prism spaces, and increased cross-striation of the prisms. Amorphous substances of brown color may appear, highlighting the defective mineralization and structural formation of the enamel.

Clinical Presentation

Amelogenesis Imperfecta affects a group or all teeth in both dentitions and manifests in various forms depending on the severity of the enamel abnormalities. In mild cases, the enamel is smooth and shiny but may appear yellow or brown. In more severe cases, enamel is either completely absent or present in small patches, leading to rough, worn-down tooth surfaces. Teeth may also have cone- or cylinder-shaped forms, and discoloration ranges from yellow to dark brown.

Classification

Amelogenesis Imperfecta is classified into several types based on the extent and nature of enamel defects:

- Hypoplastic Type: Mild enamel deficiency, with smooth, shiny but discolored enamel.

- Hypomaturative Type: Impaired enamel maturation, leading to weak and discolored enamel.

- Hypocalcified Type: The enamel lacks sufficient mineralization.

- Hypoplastic-Hypomaturative Type with Taurodontism: Features both enamel deficiencies and enlarged pulp chambers, known as taurodontism, resembling "bull teeth" in X-rays.

Treatment

Treatment for Amelogenesis Imperfecta is primarily symptomatic and involves long-term care. It includes restorative procedures to protect the remaining enamel and prevent further deterioration. These may include remineralization therapy, composite fillings, crowns, or dental prosthetics to restore the tooth’s function and aesthetics.

Prevention

As Amelogenesis Imperfecta is a genetic condition, there is currently no method for prevention. However, early diagnosis and regular dental care are essential to manage symptoms and improve quality of life for affected individuals. Early intervention can minimize the extent of damage and help maintain dental health.

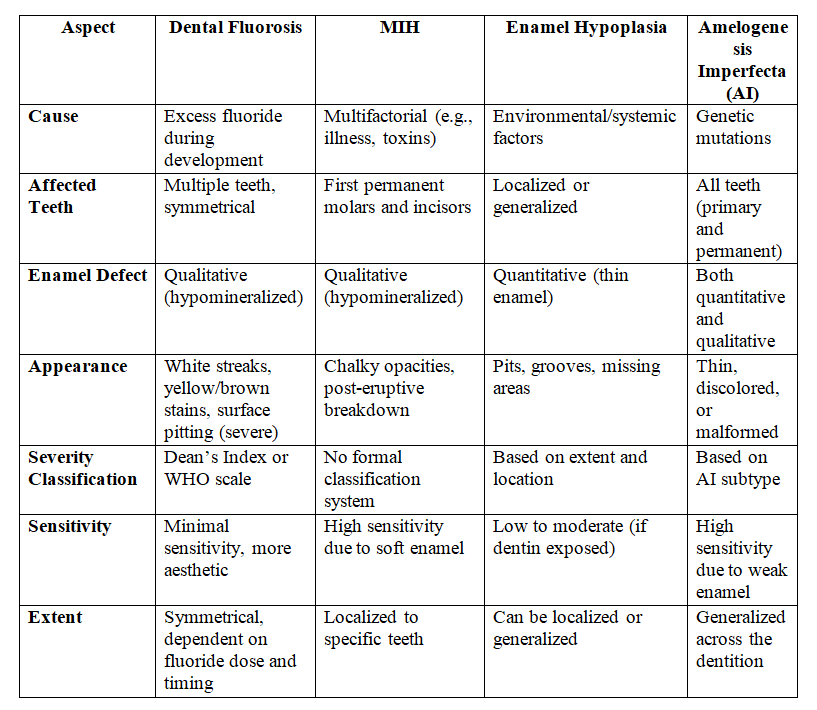

Key comparison table

Summary

- Fluorosis emphasizes symmetrical, fluoride-related changes that are often cosmetic but can involve pitting in severe cases.

- MIH and AI are more likely to impact enamel integrity and function, with MIH localized to molars/incisors and AI affecting all teeth.

- Enamel Hypoplasia is distinct in being a quantitative defect caused by systemic or local factors.

When treating disorders of tooth development, restoring the function and appearance of teeth often requires advanced prosthetic solutions. Our comprehensive course “Veneers, inlay, onlay, crowns: full protocols" provides you with detailed protocols and the latest techniques to restore damaged teeth effectively and beautifully. Whether you're dealing with congenital enamel defects, severe fluorosis, or other developmental disorders, you'll learn how to manage complex cases with confidence!

Each condition requires individualized treatment, balancing aesthetic, functional, and sensitivity concerns.