Philosophy and Writing of T-Control for Self-Ligating Passive Brackets

Machine translation

Original article is written in RU language (link to read it) .

Low friction of passive self-ligating brackets, which approaches zero when using thin orthodontic wires, provides the most physiological movement of teeth.1,2 Low friction can lead to loss of torque control,1,3-5 thus increasing the complexity of correcting rotations and torque during the finishing stage of treatment.4,5 One of the reasons for these difficulties is the smaller width and larger slot, allowing for more pronounced play of the wire in the slot, especially in the passive version of the brackets.1,5-8 With a bracket slot of .022", the loss of torque will be 7.8-23.9 degrees for a .019"x.025" wire and 2.9-8.4 degrees for a .021"x.025" wire.5,8

To enhance the expression of torque when using passive self-ligating brackets, we developed a two-dimensional prescription with variable slots and customized torque and angulation for the anterior, lateral, and distal segments. The T-Control philosophy was developed simultaneously to improve the biomechanical efficiency of passive self-ligating brackets, as well as to achieve results in the individualized treatment planning of various occlusion pathologies. This treatment philosophy includes seven important steps:

Diagnosis

Modified bracket prescription

Stops

Disengagement of dental arches

Elastics

Sequence of arches

Skeletal support

In this article, the T-Control philosophy is demonstrated through a clinical case of Class III.

Figure 1. A 15-year-old female patient with skeletal Class III pathology and inclination of the occlusal plane before treatment.

Diagnosis

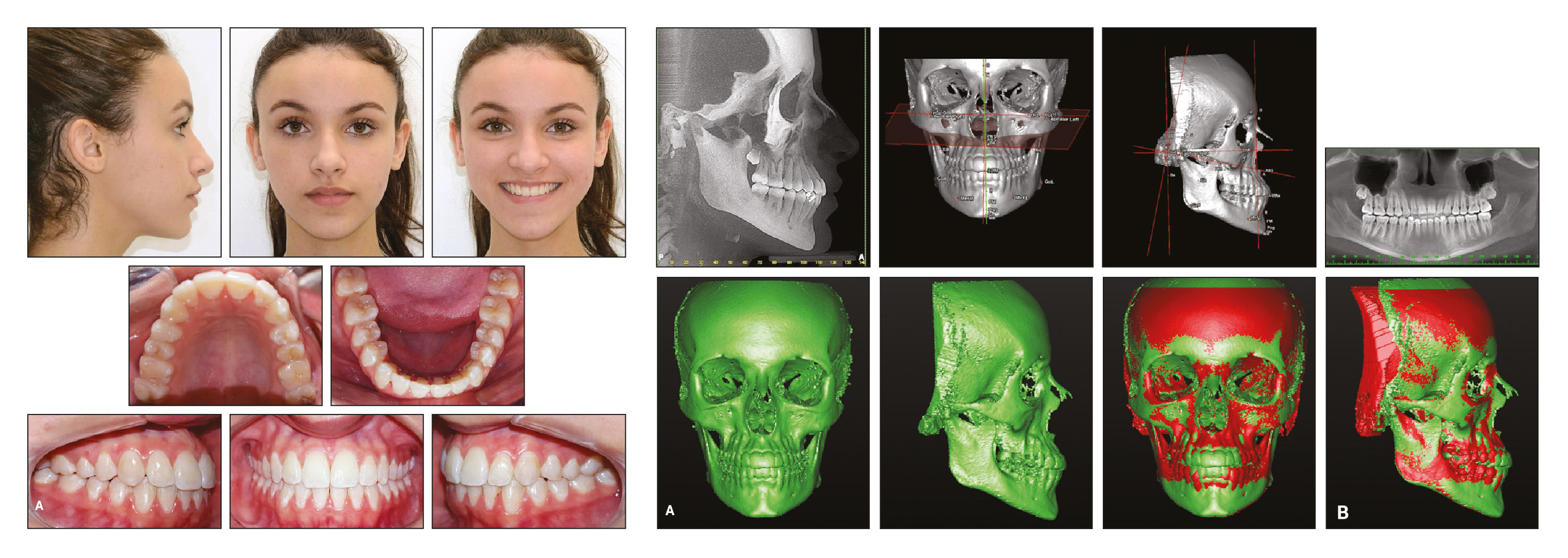

A 15-year-old female patient with a skeletal Class III anomaly and a concave profile (Figure 1). She had previously undergone orthodontic treatment using functional appliances. Clinical examination revealed: facial asymmetry, weak lip closure, smile asymmetry, and the lower midline shifted to the left. Dental occlusion is classified as Class III on both sides, with an open bite in the anterior and lateral segments, and a crossbite in the anterior and lateral segments, along with an inclination of the occlusal plane.

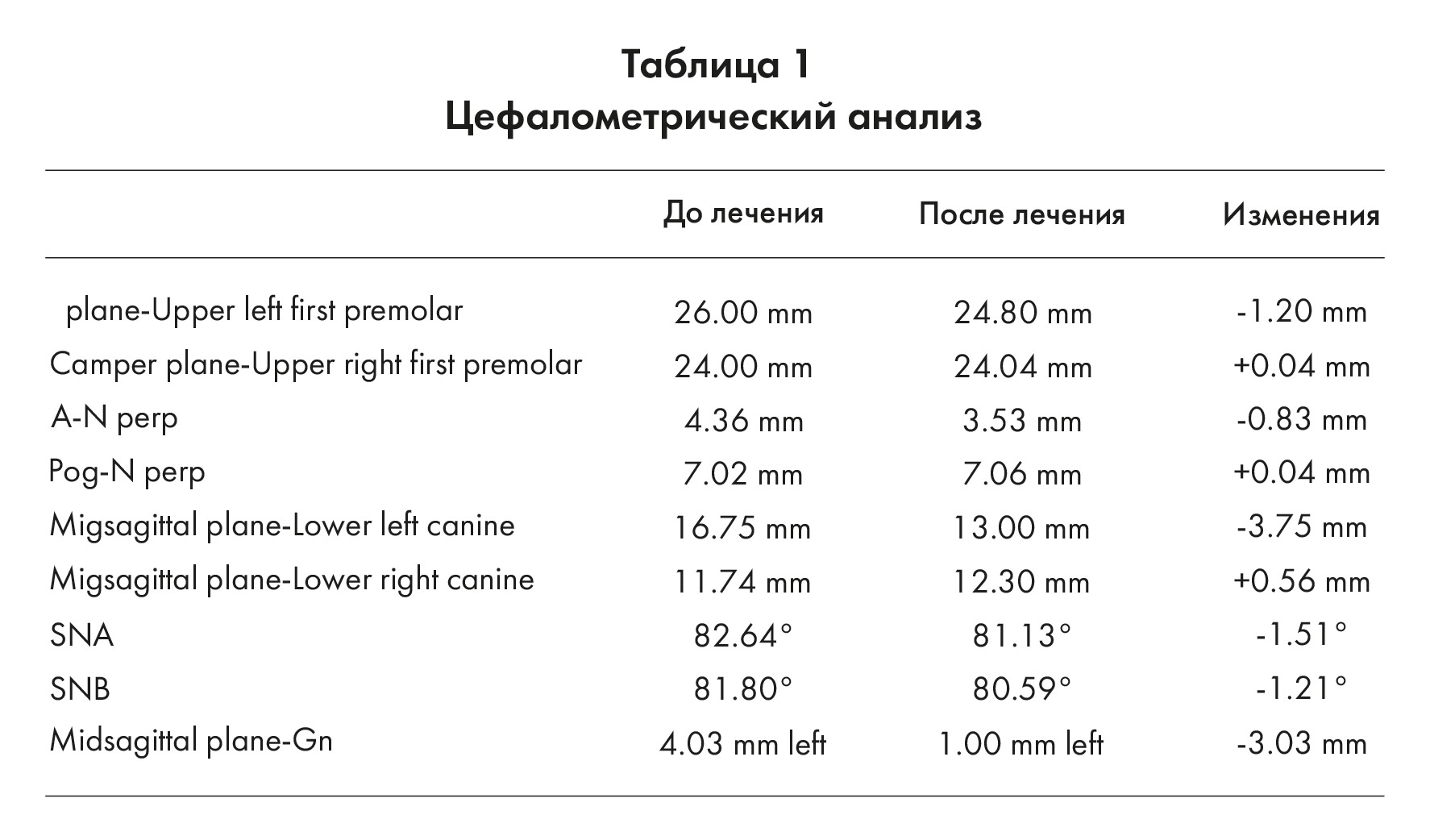

On the orthopantomogram with teeth in occlusion, unerupted third molars are visualized. Cephalometric analysis confirmed facial skeletal asymmetry and lower midline deviation, as well as an anomaly of the occlusal plane characteristic of lateral and anterior open bite (Table 1).

There was also a significant prognathism of the maxilla and an asymmetrical occlusal plane in the vertical direction.

The treatment goals include correction of Class III, dento-alveolar remodeling with tooth alignment, correction of the midline, and bilateral open bite with the achievement of aesthetic and functional results through the correction of the inclination and intrusion of the molars in the mandible.

Treatment options included: orthodontic treatment with orthognathic surgery, non-surgical compensatory orthodontics with the extraction of the first premolars in the mandible, or a less traditional approach involving the distalization of the teeth in the mandible with skeletal support using mini-plates or mini-screws. We recommended compensatory orthodontic treatment using the T-Control philosophy with passive self-ligating brackets.

Tooth extractions are a serious issue when using passive self-ligating brackets; the decision must consider not only the degree of crowding but also the facial profile, nasolabial angle, muscle tone, buccal corridors, and lip closure. In the case presented here, only the third molars of the upper and lower jaws were extracted, as the patient had a Class III malocclusion associated with an increase in the size of the maxilla in the vertical plane and a shortening in the sagittal plane.9-11

Modified Prescription

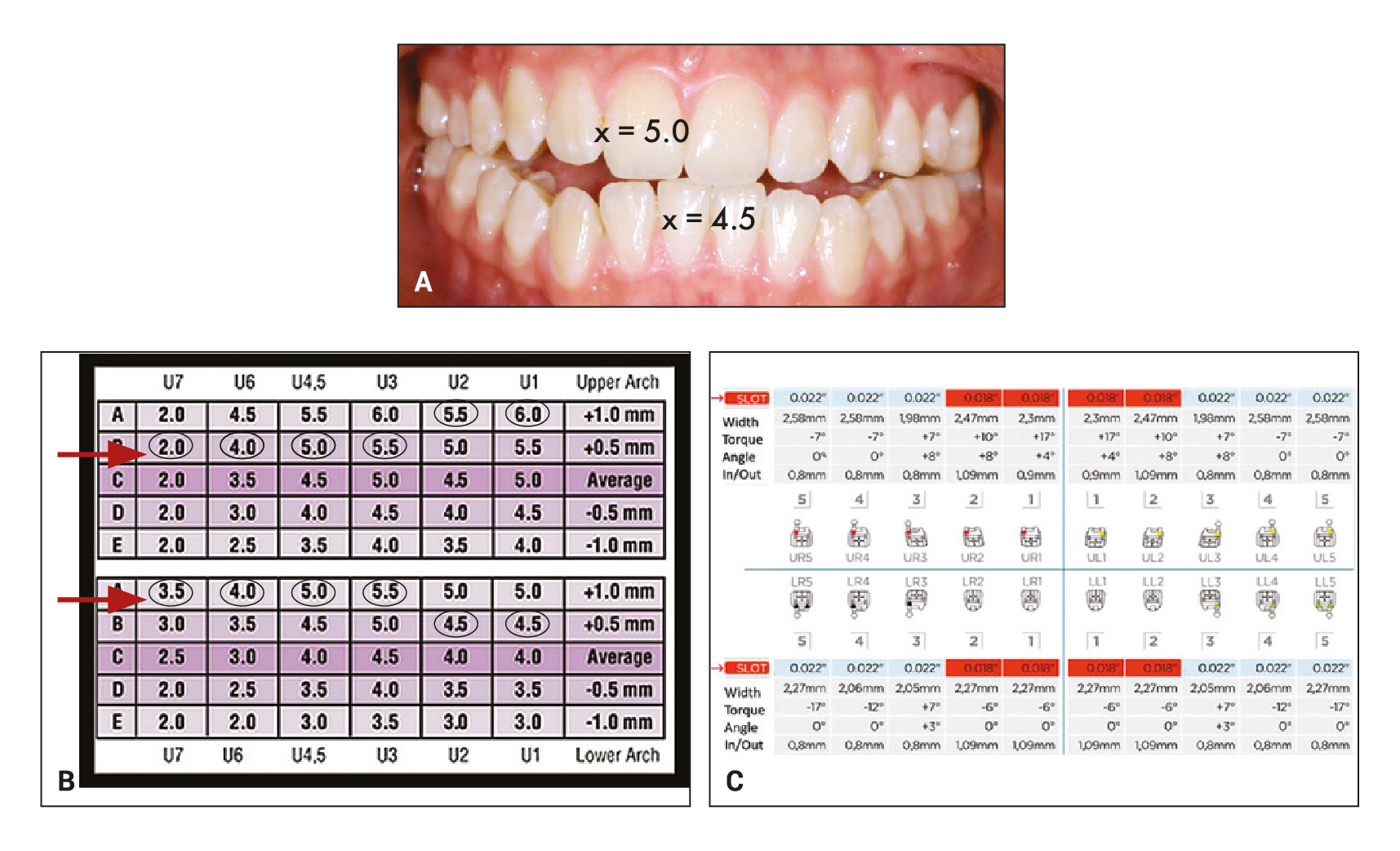

The T-Control prescription is an individualized, modified MBT (Figure 2).12-16 We used metal passive self-ligating brackets. In the T-Control prescription, the brackets for incisors have slot sizes of .018x.028, while the brackets for canines, premolars, and molar tubes are .022x.028 with specific torque and angulation values for each segment of the arch.

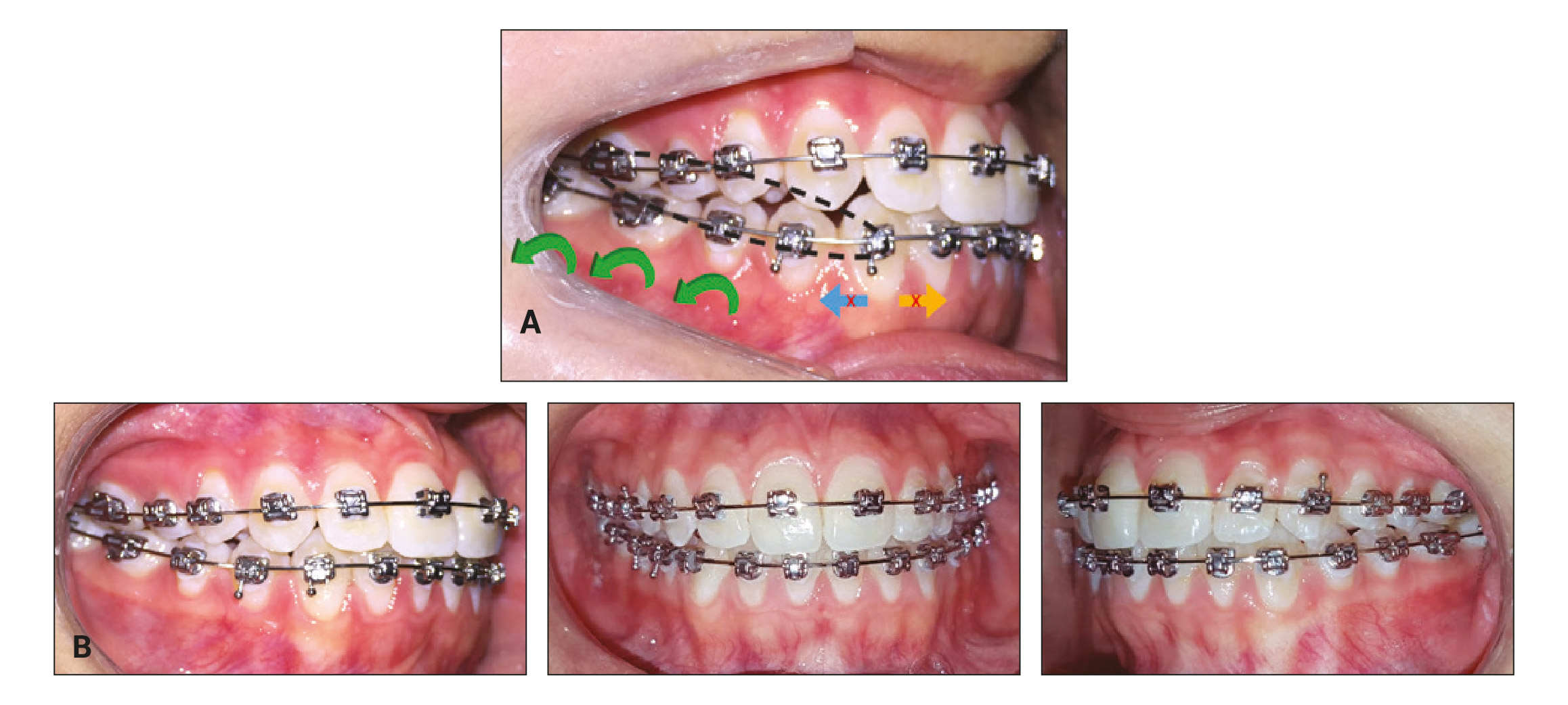

In our Class III treatment case, brackets were bonded to the upper dental arch at a level of .5mm on the central and lateral incisors during the first visit, and a .014 archwire made of a copper, nickel, and titanium alloy was placed (Figure 3). After 4 weeks, during the second visit, brackets were bonded to the lower dental arch at a level of .5mm on the central and lateral incisors (Figure 4).

Figure 2. A. Maxillary and mandibular torque values are based on measurements taken from the MBT prescription. B. Example of a smile arch protection prescription with highlighted personalization. C. T-Control prescription with slot dimensions, bracket width, angulation, torque, in-out value.

Stops

Stops can be made of metal in the form of round or rectangular/square cross-section tubes or made from a flowable composite material. Stops are used to direct orthodontic tooth movements and to enhance patient comfort after arch placement, provided that passive self-ligating brackets have extremely low friction.2,17 In this clinical case, metal stops were placed mesially from the second upper left and right molars to stimulate the advancement of the upper dental arch, known as the "omega effect".

Initially, the arches were positioned inside the stops passively (with a gap of about 1 mm), but later the stops were tightened closely to work in conjunction with the arch. In the lower arch, stops were placed on the distal sides of the right first premolar and left second premolar during the second appointment. They helped control buccal tipping during the initial alignment of the teeth in the anterior segment.

Figure 3. Passive self-ligating brackets T-Control with a thin wire of low strength .014 made of a copper, nickel, and titanium alloy installed during the first visit.

Disjunction of dental arches

Devices for disjunction of dental arches are made from glass ionomer cements, composites, or other materials. They facilitate the repositioning of the mandible into a centric relation by disjunction of the dental arches. They also help to correct the inclination of the occlusal plane. They can be fixed on various surfaces, including the occlusal surfaces of the posterior teeth, palatal surfaces of the maxillary canines and incisors (bite pads), or lingual surfaces of the mandibular teeth.

In this clinical case, composite pads for disjunction of dental arches were placed on the upper right second molar and the upper left first and second molars. The bite was positioned higher on the left side (the side of the mandibular shift).18

Elastics

Intermaxillary elastics can be used in the early stages of treatment in conjunction with passive self-ligating brackets to direct and control tooth movement.18,19 Weaker elastics should be used with thin orthodontic wires. Due to low friction, tooth movement will be more efficient than with traditional ligature brackets.2,3,7 In the presented clinical case, starting from the second visit, light class III elastics (5/16", 60-80 g) were applied from the upper right first molar to the lower right first premolar and from the upper left first molar to the lower left first premolar, worn for at least 16 hours a day.

The force and duration of wear should increase with the thickness of the wire. The main biomechanics of class III correction began with the installation of a .014 x .025 alloy of copper, nickel, and titanium. In this case, we recommended wearing medium strength class III intermaxillary elastics (3/16", 150-200 g) throughout the day (Figure 5). A separating spring was placed between the lower right canine and premolar to neutralize the force of the elastic on the canine and enhance the distalization of the lower molar, controlling its tilt.20,21 To correct every 15 degrees of tilt, an increase in the length of the dental arch of approximately 10 mm is required.20,22,23 Additionally, the lower third molars were removed prior to treatment to prevent any obstruction that could hinder distal movement.17,23 Only class III elastics were used on the left side.22,23

Figure 4. Four weeks after the start of treatment.

Sequence of arches

In this technique, light arches made of a copper, nickel, and titanium alloy of universal sizes were used.20 To achieve physiological transverse remodeling from the very beginning of treatment, the arch for the upper dental arch was applied to the lower dental arch. The usual sequence of arches: .013" or .014" (depending on the degree of crowding), .016", .014"x.025" and .017"x.025", then steel or TMA arches .017"x.025" and/or .016"x.022" steel or TMA for the finishing stage. The finishing arches are always personalized according to the patient's WALA ridge.20,21

In the clinical case under consideration, composite overlays for bite separation were removed after 24 weeks, during the installation of arches made of a copper, nickel, and titanium alloy sized .017"x.025".19,24,25 Another 8 weeks later, finishing arches made of steel .017"x.025" were installed.

Figure 5. A. After 20 weeks of treatment using T-Control biomechanics for Class III treatment with medium strength intermaxillary elastics for Class III. The opening nitinol spring, located between the lower right canine and the first premolar, opposes the force of the elastic and improves the distalization of the lower left molar, controlling its tilt. B. After 14 months of treatment.

skeletal anchorage

Different types of skeletal anchorage using mini-screws can be used as a supplement if necessary.26,27 In the described clinical situation, skeletal anchorage was not used.

Treatment results

After 18 months of treatment, the patient achieved improvement in occlusion, chewing, diction, and swallowing function (Figure 6). Facial and smile aesthetics significantly improved. Cephalometric analysis (Table 1) and tomography confirm the correction of asymmetry and the occlusal plane.

Figure 6. A. Patient 18 months after treatment. B. Overlay of tomograms before and after treatment.

Conclusion

Although the two-dimensional concept had been proposed earlier,28-32 including for use with active self-ligating brackets,33 our approach appears to be the first for passive self-ligating brackets. The use of two slot sizes provides biomechanical advantages, including free sliding of the posterior tooth groups during space closure and minimization of frictional forces during retraction. This differential approach allows for the use of a wider orthodontic archwire with a diameter of .017", thereby maintaining .04" of free space in the .022" slots of the canine and premolar brackets. As a result, during canine retraction, anterior retraction, and posterior protraction, the mechanics of free sliding are applied, while the torque of the anterior group remains constant.29,32 The T-Control philosophy allows for individual prescription while the sequence of orthodontic archwires enhances the expression of torque and angulation.34

Compensatory orthodontic treatment is an acceptable alternative to orthognathic surgery for correcting occlusal relationships in cases with mild mid-facial discrepancies.35 The ideal patient for compensatory treatment is one who has ongoing growth and moderate crowding with space for tooth extraction, allowing for successful orthodontic camouflage.34,35 Vertical changes in the occlusal plane have growth-related implications for the position of the mandible, which in some cases enhances the stability of compensatory treatment.36-38

Skeletal Class III malocclusion, characterized by an anteroposterior discrepancy between the sizes of the bases due to underdevelopment of the maxilla, enlargement of the mandible, or both together usually requires orthognathic surgery,39,40 although skeletal anchorage currently offers an alternative for predictable orthodontic treatment.35 Patients who refuse surgery due to its risks and costs,40 if they are relatively satisfied with their appearance and do not have TMJ dysfunction requiring surgical intervention, may opt for dental compensation without complete and ideal correction of skeletal anomalies.

As a rule, when treating any class III, tooth extraction should be avoided, as this malocclusion is corrected by rotating the lower jaw backward and, consequently, promoting vertical growth. Since the morphology of soft tissues does not always correspond to the morphology of hard tissues, assessing facial aesthetics has become an important component of diagnosis.38 If the patient's skeletal issues do not affect the face, compensatory treatment may be possible. However, to avoid being misled by a posterior crossbite resulting from pseudoprognathism,30,40 a preliminary analysis of the jaw models, aligned in Class I relationship on both sides, should be conducted. This provides a more accurate representation of the maxilla structure and the crossbite in the posterior segments. If the models show negative overjet or reverse incisor overlap, there is a certain need for maxillary expansion.38,41

The patient's cooperation is key to treatment using intermaxillary elastics. In the case described here, the patient was informed about the benefits of wearing Class III elastics, and her excellent compliance contributed significantly to the success of the treatment.21,34,38,41

References

1. Dalastra, M.; Eriksen, H.; Bergamini, C.; and Mensen, B.: Actual versus theoretical torsional play in conventional and self-ligation bracket systems, J. Orthod. 42:103-113, 2015.

2. Ehsani, S.; Mandich, M.A.; El-Bialy, T.H.; and Flores-Mir, C.: Frictional resistance in self-ligating orthodontic brackets and conventionally ligated brackets: A systematic review, Angle Orthod. 79:592-601, 2009.

3. Al-Thomali, Y.; Mohamed,

R.N.; and Basha, S.: Torque expression in self-ligating orthodontic brackets and conventionally ligated brackets: A systematic review, J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 9:123-128, 2017.

4. Sathler, R.; Siva, R.G.; Janson, G.; Branco, N.C.C.; and Zandam, M.: Demystifying the self-ligating brackets, Dent. Press J. Orthod. 16:50e1-e8, 2011.

5. Melenka, G.W.; Nobes, D.S.; Carey, J.P.; and Major, P.W.: Three-dimensional deformation comparison of self-ligating brackets, Am. J. Orthod. 143:645-657, 2013.

6. Damon, D.H.: The Damon low-friction bracket: A biologically compatible straightwire system, J. Clin. Orthod. 32:670-680, 1998.

7. Pacheco, M.R.; Oliveira, D.D.; Smith Neto, P.; and Jansen, W.C.: Evaluation of friction in self-ligating brackets subjected to sliding mechanics: An in vitro study, Dent. Press J. Orthod. 16:107- 115, 2011.

8. Badawi, H.M.; Toogood, R.W.; Carey, J.P.; Hei, G.; and Major, P.W.: Torque expression of self-ligating brackets, Am. J. Orthod. 133:721-728, 2008.

9. Janson, G; de Souza, J.E.; Alves, F.A.; Andrade, P. Jr.; Nakamura, A.; de Freitas, M.R.; and Henriques, J.F.: Extreme dentoalveolar compensation in the treatment of Class III malocclusions, Am. J. Orthod. 128:787-794, 2005.

10. Kim, K.M.; Sasaguri, K.; Akimoto, S.; and Sato, S.: Mandibular rotation and occlusal development during facial growth, J. Stomatol. Occ. Med. 2:122-130, 2009.

11. Sato, S.: Case report: Developmental characterization of skeletal Class III malocclusion, Angle Orthod. 64:105-111, 1994.

12. McLaughlin, R.P. and Bennett, J.C.: Bracket placement with the preadjusted appliance, J. Clin. Orthod. 29:302-311, 1995.

13. Sarver, D.M.: The importance of incisor positioning in the esthetic smile: The smile arc, Am. J. Orthod. 120:98-111, 2001.

14. Brandão, R.C.B. and Brandão, L.B.C.: Finishing procedures in orthodontics: Dental dimensions and proportions (microesthetics), Dent. Press J. Orthod. 18:147-174, 2013.

15. Câmara, C.A. and Martins, R.P.: Functional aesthetic occlusal plane (FAOP), Dent. Press J. Orthod. 21:114-125, 2016.

16. Epstein, M.B.: Benefits and rationale of differential bracket slot sizes: The use of 0.018-inch and 0.022-inch slot sizes within a single bracket system, Angle Orthod. 72:1-2, 2002.

17. Higa, R.H.; Henriques, J.F.C.; Janson, G.; Matias, M.; de Freitas, K.M.S.; Henriques, F.P.; and Francisconi, M.F.: Force level of small diameter nickel titanium orthodontic wires ligated with different methods, Prog. Orthod. 18:21-28, 2017.

18. Hardy, D.K.; Cubas, Y.P.; and Orellana, M.F.: Prevalence of Angle class III malocclusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Open J. Epidemiol. 2:75-82, 2012.

19. Hisano, M.; Chung, C.R.; and Soma, K.: Nonsurgical correction of skeletal class III malocclusion with lateral shift in an adult, Am. J. Orthod. 131:797-804, 2007.

20. Miura, F.; Mogi, M.; Ohura, Y.; and Hamanaka, H.: The super-elastic property of the Japanese NiTi alloy wire for use in orthodontics, Am. J. Orthod. 90:1-10, 1986.

21. Gravina, M.A.; Canavarro, C.; Elias, C.N.; Chaves, M.G.A.M.;Brunharo, I.H.V.P.; and Quintão, C.C.A.: Mechanical properties of NiTi and CuNiTi wires used in orthodontic treatment, Part 2: Microscopic surface appraisal and metallurgical characteristics, Dent. Press J. Orthod. 19:69-76, 2014.

22. Capistrano, A.; Cordeiro, A.; Siqueira, D.F.; Capelozza Filho, L.; Cardoso, M.A.; and Almeida-Pedrin, R.R.: From conventional to self-ligating bracket systems: Is it possible to aggregate the experience with the former to the use of the latter? Dent. Press J. Orthod. 19:139-157, 2014.

23. Woon, S.C. and Thiruvenkatachari, B.: Early orthodontic treatment for Class III malocclusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Am. J. Orthod. 151:28-52, 2017.

24. Hanashima, M.; Sakakibara, K.; Slavicek, R.; and Sato, S.: A study regarding occlusal plane and posterior disocclusion, J. Stomatol. Occ. Med. 1:27-33, 2008.

25. Philippe, J.: Treatment of deep bite with bonded biteplanes, J. Clin. Orthod. 30:396-400, 1996.

26. Creekmore, T.D. and Eklund, M.K.: The possibility of skeletal anchorage, J. Clin. Orthod. 17:266-269, 1983.

27. Kyung, H.M.; Park, H.S.; Bae, S.M.; Sung, J.H.; and Kim, I.B.: Development of orthodontic micro-implants for intraoral anchorage, J. Clin. Orthod. 37:321-328, 2003.

28. Gianelly, A.A.; Bednar, J.R.; and Dietz, V.S.: A bidimensional edgewise technique, J. Clin. Orthod. 19:418-421, 1985.

29. Giancotti, A. and Gianelly, A.A.: Three-dimensional control in extraction cases using a bidimensional approach, World J. Orthod. 2:168-176, 2001.

30. Gioka, C. and Eliades, T.: Materials-induced variation in the torque expression of preadjusted appliances, Am. J. Orthod. 125:323-328, 2004.

31. Siatkowski, R.E.: Loss of anterior torque control due to variations in bracket slot and archwire dimensions, J. Clin. Orthod. 33:508-510, 1999.

32. Franco, E.M.F.; Valarelli, F.P.; Fernandes, J.B.; Cançado, R.H.; and Freitas, K.M.S.: Comparative study of torque expression among active and passive self-ligating and conventional brackets, Dent. Press J. Orthod. 20:68-74, 2015.

33. Epstein, M.B. and Epstein, J.Z.: Dual slot treatment, Clin. Impress. 10:1-11, 2001.

34. Lin, J. and Gu, Y.: Preliminary investigation of nonsurgical treatment of severe skeletal Class III malocclusion in the permanent dentition, Angle Orthod. 73:401-410, 2003.

35. Ngan, P. and Moon, W.: Evolution of Class III treatment in orthodontics, Am. J. Orthod. 18:141-159, 2015.

36. Stellzig-Eisenhauer, A.; Lux, C.J.; and Schuster, G.: Treatment decision in adult patients with Class III malocclusion: Orthodontic therapy or orthognathic surgery? Am. J. Orthod. 122:27-37, 2002.

37. Tanaka, E.M. and Sato, S.: Longitudinal alteration of the occlusal plane and development of different dentoskeletal frames during growth, Am. J. Orthod. 134:1-11, 2008.

38. Almeida, M.R.; Almeida, R.R.; Oltramari-Navarro, P.V.; Conti, A.C.; Navarro, R.L.; and Camacho, J.G.: Early treatment of Class III malocclusion: 10-year long-term clinical follow-up, J. Appl. Oral Sci. 19:431-439, 2011.

39. Lee, H.C.; Park, H.H.; Seo, B.M.; and Lee, S.J.: Modern trends in Class III orthognathic treatment: A time series analysis, Angle Orthod. 87:269-278, 2017.

40. Akan, S.; Kocadereli, I.; and Tuncbilek, G.: Long-term stability of surgical-orthodontic treatment for skeletal Class III malocclusion with mild asymmetry, J. Oral Sci. 59:161-164, 2017.

41. Teixeira, A.O.B.; Medeiros, J.P.; and Capelli, J.: Orthosurgical intervention in adolescent patients with marked Class III skeletal dysplasia, Rev. Dent. Press Orthod. Facial Orthop. 12:55-62, 2007.